Of Gatherings: Meandering through the City

I first met some of the artists of the first draft collective in Delhi in summer, 2024. In pursuing a research project on art collectives and urban experience, a friend recommended that I meet them and hear about their gathering practice. In this essay, the artists chronicle a series of recent gatherings that they have initiated, in Delhi and beyond, and the themes that emerged from these meetings. While the conversations among participants are the most tangible takeaway from these events, these are not presented here for needs of brevity. Gathering is a time-based media, a form of social practice, and a community-building exercise, so capturing the dynamic can be tricky in written form. This is the second of a two-part series on these gatherings. Printing this series in Roborant Review is a means of expanding the geographical scope of the journal while also inviting artists to write about practices whose results fall outside the scope of an exhibition.

- John Zarobell

To capture that which escapes form, that lives in collective memory, in a momentarily shared time and space, that which diffuses and takes slippery forms when people leave, that has always already existed in a primordial form of life.. is the dilemma the collective faces when trying to revisit, reconceptualise or categorise gatherings as an artistic practice. This article shares the same dilemma. In June, we gathered to reflect on the reciprocal relationship between the gatherings and the city. While it was a step to bridge this gap by making its transcription public, the condensed parts, here, become a glimpse at the expansive four-hours of conversations1 .

In Part 1 of the essay, the tripartite of the social, the public and the community becomes an anchor for us to seek intimacy through gatherings, and operate within the city's existing structures while also trying to disobey them. A gathering evokes a surplus from the place where we gather, beyond what is given to us, what the place can afford and how we can demand more from it. Affordances are inherently relational; they describe the relationship between an individual or a group's capabilities and the environment's offerings. They are not just about what the space is, but also about what the space allows or disallows in terms of action. Affordances are not fixed but emerge with the interactions. The space may have many affordances, but only a few might be relevant to a specific agent's capability, goals and social contexts2

To gather. To parkour through the city. To tease its affordance.

In parkour3 , a person traverses the cityscape, teasing its rigid and defined movements. A gathering can become that attempt to parkour, in the way that we are going to a building's terrace, expanding its affordance. There is a purpose of the terrace, it is closer to the sky, so we gathered to talk about night and sky, we brought the city into it. Or. We are walking in a garden, and the garden's original purpose is still being fulfilled, it's not being denied, but its affordance magnifies when we talk about the very site we are at. Or. The place for the walking-gathering with artist Nick Ferguson was chosen in a way that the location informs the conversations, it would be completely different elsewhere. Or. To gather in a Falcha4 in Patan (a community space where the locals gather daily), to talk about 'What brings us together?' , and the cultural significance and architecture of a Falcha itself. Or. When gathering in Aizawl to talk about Mizoram's culture, history, gender roles. Aizawl being called a silent city, what then this silence implies and amplifies?

Some 10-12 of us lay down facing the sky, talking about its wilderness, its freedom, dreams, the leap of imagination that it allows with its opacity and mystery. Although it is part of the city's stratosphere affected by the city's atmosphere, the air and light pollution, sound of planes— all of it, yet it feels out of reach and infinite. We read Sylvia Plath's I am Vertical5 (but I would rather be horizontal), and searched for the almost invisible stars clouded by the light around us, through a stargazing app that simulated constellations, the moon, the sun and its planets. The city and its technologies have replaced the sky, or rather, constructed a new sky, an artificial roof that reflects our urban life.

'(Im)mobility- In Pursuit of Legacy'

A gathering, in collaboration with Nick Ferguson, was realised through a walk along the Central Vista from Delhi's India Gate towards the presidential palace. The prompt was 'mobility' and was accompanied on the day with a printed layout plan of Imperial Delhi, a document thought to reflect the original 1912 conception of the vista by British architect Edwin Lutyens.

'Issues around statecraft, democracy and civic space surfaced repeatedly over the course of the evening. For some, the language of power is the same whoever is in power, wherever you are in the world. There are the same straight vistas, fountains, monuments and lawns. To this extent, New Delhi offered a blueprint for how power might be spatialised. We asked who had access and how this has changed over the course of time. As if by way of portent, this conversation was drowned out by a dusk gathering of birds in a nearby tree. They seemed to be protesting or at the very least expressing strong views. Whatever their precise purpose, they were certainly asserting the right to crowd the public sphere. Forced to listen, we paused for a Samosa6.

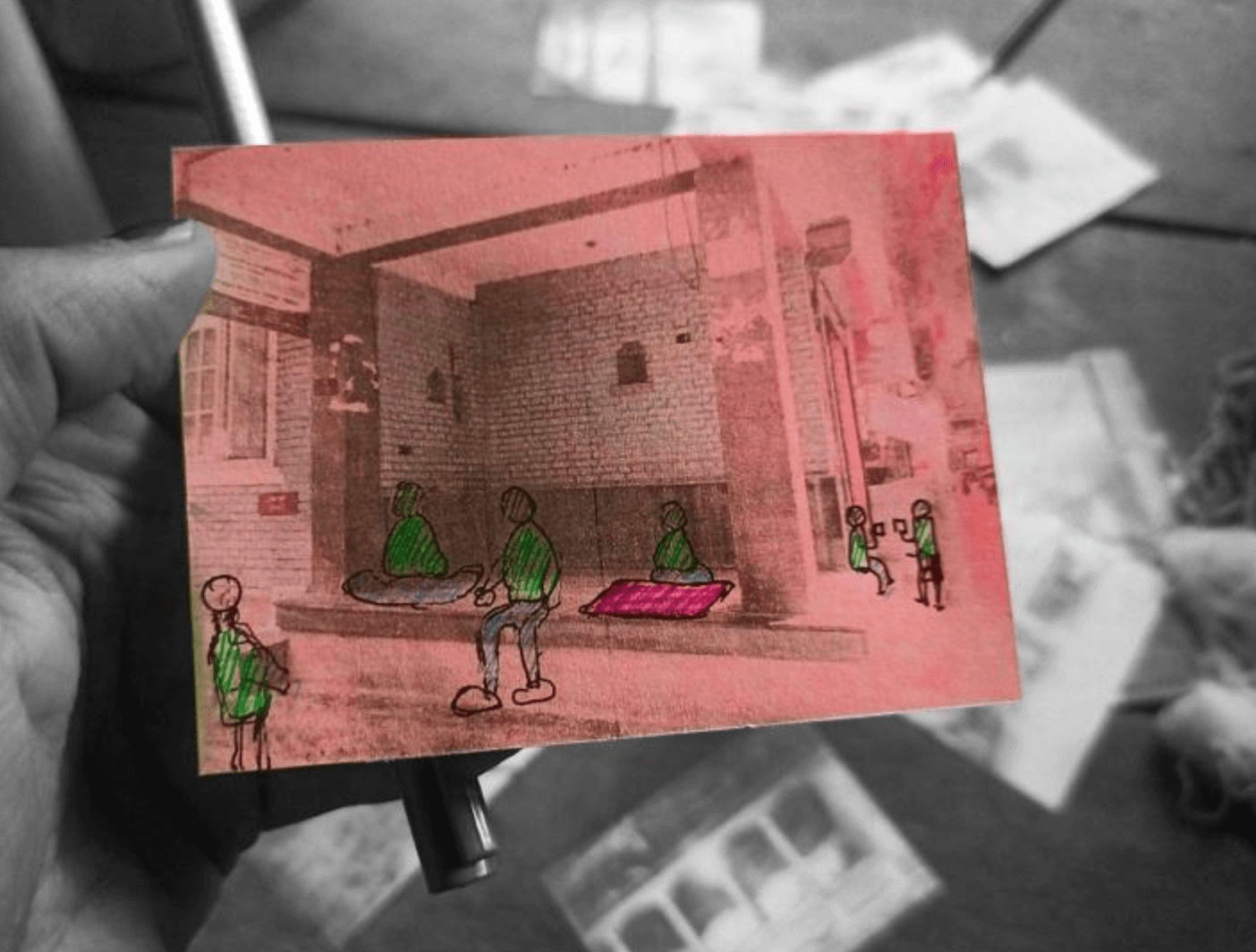

In another gathering in Patan, Nepal, at one of the community Falchas near Kaalo.101, since the city already has a cultural history integrated with these architectural spaces of coming together, doing a gathering there seemed natural and comforted the conversational flow. A density of conversations emerged around the prompt- What brings 'us' together? From the question of what 'us' means for each of us in the South Asian context, to the cultural significance of Falcha as a locus for communal activities, its architecture, history and present sustenance in a tourism-centred economy, to personal memories, stories and observations shared by each, the gathering built a slow and relaxing atmosphere. It took the prompt from the site itself by amplifying its affordance, and opened up questions around the idea of 'public space'— like parks in modern planning, and 'community space'- like Falcha in the older social structures. How a public space, maintained by civic bodies and RWAs, has a homogeneity, impersonal character and remoteness from the local populace, while a community space is cared for by the locals, has an intimacy and semi-private relation to the community that holds them together through gatherings.

The neighboring Falchas saw impromptu gatherings emerge as the evening settled and people came out to relax. The passers-by looked with curiosity, and made us conscious of how the multiple shapes of 'us' are forming, co-existing, some wanting to join in, some keeping a distance, some smiling and walking past, some just lingering nearby to listen in.. The rectangular structure of the Falcha, the wooden floor, sound of Dasain celebrations, rooftop dances and the setting sun, all shaped and joined the gathering of 'us' . As people started leaving, the gathering also transitioned and merged with the city, carrying the conversations while walking--at the restaurant for dinner--back at Kaalo-- again a midnight walk on the quiet streets of Patan--one gatherer took us though a tiny door, a low ceiling stairs that opened into a little cosy anarchist library, late midnight.

When gathering in different locations, each informs and expands the bureaucratic demarcations of a city-district-town-village–- , from the singular terminology to a multiplicity of lives whirling (in) them. While planning a gathering in Aizawl with an artist-friend, Bazik Thlana, the idea of the silent city emerged, which also became the prompt. The conversations gravitated towards how Mizo culture adopts silence, and where not speaking is misread as an adjustment or consent. However, silence is an active part of communication, particularly in terms of gender where women in a family play a very silent and important role in finding the balance between the others.

A counter argument to the narrative was posed by Thlana, who said that Mizo people don't believe in imposing themselves on others and silence is very much part of the culture of being communicative. Silence in any form, be it in traffic, public life, or in conversations, has a deep consideration towards the other's comfort; an empathic society that thinks sensitively about the other but not in a self-suppressing or self-sensoring manner but that which emboldens interpersonal relations in a society. Where silence is a tool louder than words, and not a weakness to tolerate the other by putting their needs above yourself and self-harming in the process. The context, spiralling from the Mizo culture, became relevant to the broader society, and resonated with each of us7 . A gathering on gathering the city. Within and beyond.

Priyesh: Anarya, come a little forward…

Akshay: Inside the frame, in the window panel…

[Anarya grunts while moving]

[Priyank jumps onto the bed] [Sonam laughs inside her diary]

[Everyone poses]

Through the window—the colony's parking; an electrical transmission tower; a water tank located in the campus of Jawaharlal Nehru University; JNU's forest adjacent to Sanjay Van, a vast reserved forest area close to the Qutub Minar; all part of the Aravallis (present-day South Central Ridge). The window glass reflects a phantom image of the group posing in a DDA apartment in Vasant Kunj, resting against a double bed, in the background there is a wooden jaali carved in Mughal style, surrounded by other furniture and a cosy home environment. The city and the home, the public and private merge in the reflection of the gathering. In a capitalist system that feeds off grief, dissatisfaction and wanting8 , the joy and fulfillment of gathering, converging, being in another's company, its tensions and intimacies, become a small but deeply moving form of resistance today9 .

Endnotes for Part 2:

Carson, A. (1998). Verse. Vintage Contemporaries. "XXXII. Kiss," Autobiography of Red: A Novel in

Gibson, J. J. (1977). The Theory of Affordances. Houghton-Mifflin Co.

Tani, S. (2024). The institutionalization of parkour: blurring the boundaries of tight and loose spaces. Social & Cultural Geography, 25(4), 658–676. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2023.2199707

Maharjan, Reena. (2025). Cultural History and Community Solidarity of Falcha in Kirtipur. Shahid Kirti Multidisciplinary Journal.

Plath, S. (1981). "I Am Vertical". The Collected Poems, HarperCollins.

Ferguson, N. (2024). (Im)mobility - In Pursuit of Legacy // footnotes and reflections.

Thlana, Bazik.(2025) In conversation during a gathering in Zotlang, Aizawl, Mizoram.

"Connected and Alone. " Al Jazeera, www.aljazeera.com/video/aljazeerauntangles/2025/8/6/connected-and-alone .

Haig, Matt.(2015) Reasons to Stay Alive. Canongate Books.

Day, Meagan. (2025). Americans Are Abandoning the Communal Meal. jacobin.com/2025/10/solo-dining-communal-meals-us. Rajnarayan Chandavarkar in his 1981 book, Workers' politics and the mill districts in Bombay between the wars. Modern Asian Studies, 15(3), 603–647, makes an important claim for the agency of the Bombay factory workers. He argues that the organisation of workers and their coordinated actions did not rely on nationalist or communist influences, nor on efforts from any labour unions. Instead, the collective consciousness of the workers was shaped by the mobilisation of their social relationships in their neighbourhoods. He notes the involvement of various agents and informal spaces, such as pleaders' offices, streets, jobbers' and dadas' networks, Akhadas, shops, and various neighbourhood centres, where workers gathered and which became the source of their coordinated actions.

Vigliar, Virginia. (2024). @vivivigliar. Play is a revolutionary force. "Instagram" . https://www.instagram.com/p/C-GH3VxocF-/?img_index=1