Nigel Poor

Nigel Poor lives and works in the Bay Area. Her work has been shown at many institutions including, The San Jose Museum of Art, Institute of Contemporary Art, San Jose, Friends of Photography, SF Camerawork, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the San Diego Museum of Contemporary Art, Museum of Photographic Arts, San Diego, Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. and the Haines Gallery in San Francisco. Her work can be found in many collections including the SFMOMA, the M.H. deYoung Museum, San Diego Museum of Contemporary Art and Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington D.C. She received her BA from Bennington College and her MFA from Massachusetts College of Art.

In 2011 Nigel’s interest in investigating the marks people leave behind led her to San Quentin State Prison where she taught history of photography classes for the Prison University Project. This experience changed the focus of her practice and the visual presentation of her ideas. She has since moved away from being a solely visual artist working alone in the studio and now spends the majority of her “studio” time inside the prison working with a group of mostly lifers on photographic projects and producing radio stories about life inside.

Nigel Poor is a Professor of Photography at California State University, Sacramento, and a member of the Bay Area photo collective Library Candy.

The following are excerpts from Nigel Poor’s interview with Hugh Leeman.

Hugh Leeman: Nigel, early in your career, you worked in Harvard's entomology department, pinning insects and discovering interesting artifacts from previous collectors. Amidst this time in your life, you find a nineteenth-century note about a man who, quote, "disappeared and was assumed to have been eaten by the natives," end quote. You go on and reference this and say, "In many ways, that experience dictates the way I work now." How so?

Nigel Poor: Oh my goodness. Wow, that was a long time ago. Well, I love looking for clues and I love stories and collecting. And I don't always care if the stories are 100% true. And that story about the person disappearing had all of those things to it. It was engaging. It was maybe suspect if it was true or not. And I always think of this quote—and I believe it's from the French director—I'm going to come up with his name in a minute. Anyway, he said that you can start with fact or fiction, but inevitably one will recall the other. And I think about that a lot with my work. And I'm not talking about lying and alternative facts. It makes me think about how our memory works and how our memory is often dictated by desire to believe things, and it's hard for us to ever know the truth of something. And so I like that. I like playing with that. But again, it's not talking about alternative facts.

So that story made me think about those things. But I also loved working in that museum behind the stacks, because it was really all about obsessive collecting and thinking about if you could collect enough objects or insects, you'd be able to answer these big questions. And so I've spent my career collecting things, trying to answer big questions that are impossible to answer, but I love the process of it. So hopefully that answers your question.

HL: Absolutely. I want to get to that idea later—the idea of answering questions that are impossible to answer. Can you say that one more time? The quote from the French director that's powerful.

NP: Godard. Jean-Luc Godard. Yeah. And he said, "You can start with fact or fiction, but inevitably one will recall the other." And I think that's such a smart way to look at communication, because it's so difficult to parse fact from fiction, truth from fantasy. And in all of my work, I think about that—my visual work and the work I do with my podcast. And it's not about lies. It's not about alternative facts. It's about the way our memory works and the way we are as humans. It's very tender, it's faulty, and it's endlessly fascinating to me.

HL: The project that I'd like to hear your thoughts on—it's powerful. Reading about it, it'd be wonderful to hear some of the interior dialogue that was going on at the beginning of this. So in 2011 you began teaching photography at San Quentin State Prison. Under strict rules, there were no cameras allowed and no photography books allowed. Yet it pushed you to innovate what you called the "verbal photograph," where you ask students to remember an image from their life and describe it in writing. Can you talk about those first few classes, particularly your internal landscape of emotions as prisoners started to connect with you and with their memories?

NP: Yes. So when I started teaching that class, I was very naive. I thought I would teach it the same way I teach it at my university. And very quickly I found out that was not going to happen because no computers were allowed. In fact, the administration didn't want me to teach the class at all. Before I taught the class, I had to meet with the assistant warden and the undersecretary of the Department of Corrections and go over every image I was going to show. They at first told me that you could not have any images of violence, sex, drug use, or emotionally complicated imagery. And I was like, "What is going to be left to show? Except like maybe some banal landscapes."

So I gave a class to the undersecretary and the assistant warden, and we talked for a couple hours about photography, and at the end of that they were like, "I want to take this class." And they let me take in most of the images. There were a few I wasn't able to take in. And by bringing in the images, I mean, I had to put them on a CD and then they were projected on a TV screen in the classroom.

So that was sort of the backdrop to starting the class. And when I got into the prison, I hadn't had any experience in prison. It was all men. And I don't know why it hadn't occurred to me that the class was going to be all men. And I was really taken aback and a little bit intimidated. As the guys started filing into the classroom, I started to get nervous and wondering what I got myself into. And there was one particular guy that came in who looked really angry and he had glasses on. He sort of sat in the back, quiet.

But as soon as we started talking about photography, on my side, all of that nervousness just melted away because starting to talk about photography became this really perfect bridge to communicating and to having something that would bind us together. Because I think photography is this ubiquitous art, and it's something everybody can relate to. When I talk about photography and the history of photography and have students look at work, whether I'm teaching in prison or not, I always ask them to think about how their personal experience affects the way they understand a photograph. And it's a wonderful way to get people to open up and feel comfortable.

I wanted—and I'm going to come back to that student who I thought was angry—but I wanted the students at San Quentin to have the experience of making something, not just learning about photographs, but making something. And because cameras weren't allowed, I had to come up with alternative ways of doing it. So the first thing I thought about was this idea of the verbal photograph—of taking a memory that they believe they had, and then holding that memory in their hand and thinking of it as a still photograph and describing it in terms of point of view, perspective, scale, focus, what size is it. And take a memory that's like a film and distill it down to that one image and then describe it. And that became their verbal photograph.

One man in the class wrote about a memory of looking up and seeing his mother looking at him over his crib when he was very little, and he described the room and everything he saw. This always makes me so emotional. And at the end he said, "I'm not sure if this is my first memory or not, but it's what I want to believe is the first memory of my mother." And that goes back to that original quote about fact and fiction. You can start with one or the other, but eventually they'll reference each other. So that to me is like a beautiful example of that quote and of an example of how our minds think and how they produce images for us.

HL: The guy with the glasses who comes in and appears angry. Say more about him.

NP: Yes. So his name was Ruben Ramirez, and he became one of my best students in the class. And it was a very good lesson for me on making assumptions about people. I got to know him over the semester, and he actually became involved in a project I did about archival images. It turned out that he had just had an operation, and he was in a lot of pain. And so what I saw as anger and not wanting to be there and hiding behind sunglasses was actually someone who really wanted to come to class and not miss it, even though they were feeling really crummy.

He's such an interesting person. I don't know how old he was when he came to prison. When I met him, he was probably in his forties. He had dropped out of high school. He had really no arts education, very little education. He fell in love with photography. And at the end of the class, he said to me that because of photography, he could now see fascination everywhere. And isn't that beautiful? It's like what you hope art is going to do for somebody.

He is out now, and we're really close. I stay in touch with him. He's really gotten into photography. He shares images with me that he takes. He's just gone back to school to get his college degree in studying photography. I think he's been out for about eight years now. So we really connected through photography, became friends through photography after he got out. I don't know if we'll talk about the archive project, but there's a beautiful piece that he did for that, writing about photographs. Teaching in the prison and finding these different ways of doing assignments was incredibly fruitful for the students and for me as someone who's interested in learning new ways of communicating. The verbal photograph is an interesting one.

HL: You've brought up something I wanted to talk about later, but let's bring that forward now—the archive project. This has been something that's so powerful in your career, in your art, but it seems like it's something that really speaks to something deeply personal inside of you. What is that that's happening there?

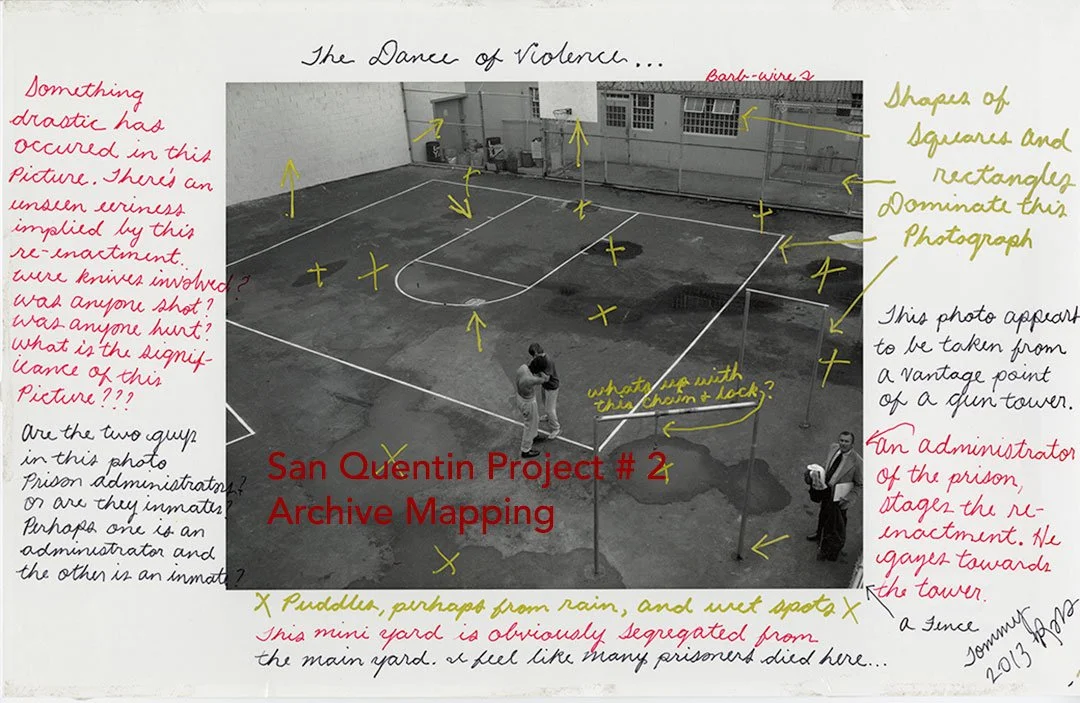

NP: Yeah. So I got access to this archive of thousands of negatives that were taken at San Quentin between the late 1930s and around 1987. And they're all four-by-five negatives. They were being kept in a banker's box and just moldering away. And when I saw them, it was like a photographer and artist dream—finding this treasure trove of unknown images. I started going through them and they're just amazing. They were oddly taken with four-by-five negatives, which I don't understand why. They were taken by correctional officers. There's not a lot of information about them.

Originally what I wanted to do besides save them was go through all of them and put them into different categories and try to use these categories to explain what life is like in prison. And one of the things that was fascinating about the images is that some of them were horrific, very violent, difficult to look at. Then there were some that were just kind of everyday images of life in prison. And then there were many beautiful images that you would never think were taken inside of prison. For example, people on family visits, people playing with animals, guys playing basketball on donkeys—very strange things. But co-mingled with the difficult images of violence and people who had died or committed suicide, and then just images that you would imagine of everyday life in prison.

So it also goes back to that fact and fiction. I didn't have a lot of experience in prison. I've never been incarcerated. So I was, as an outsider, trying to make sense of what these photographs would say about prison. And I love the discovery of them. I loved looking at just the framing and the technical side of it, as well as the stories that they seem to tell. But I knew I couldn't do the project on my own.

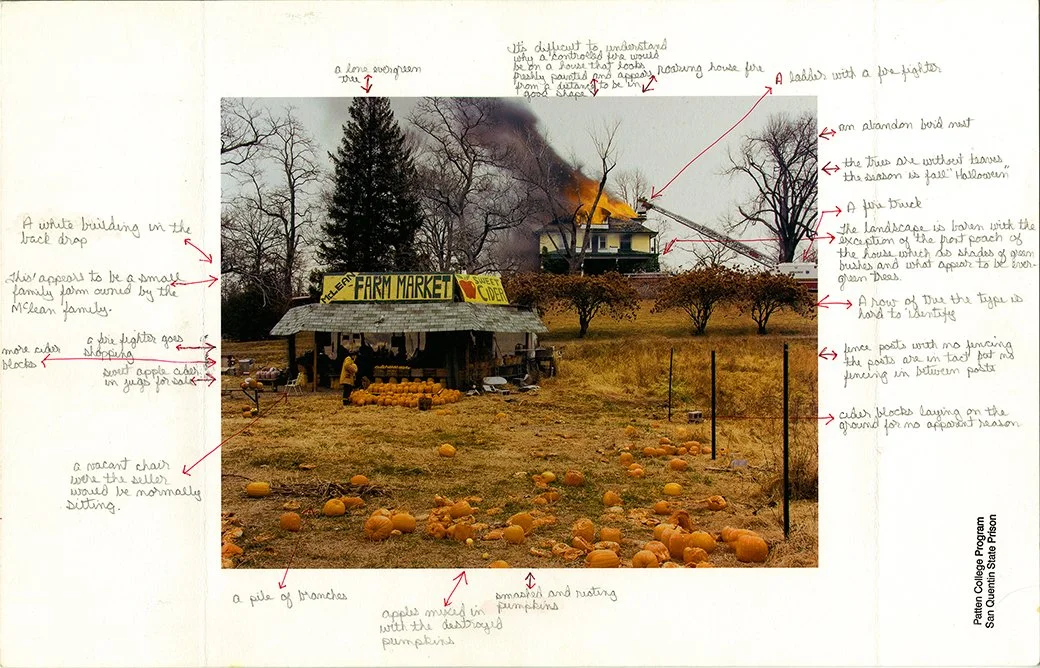

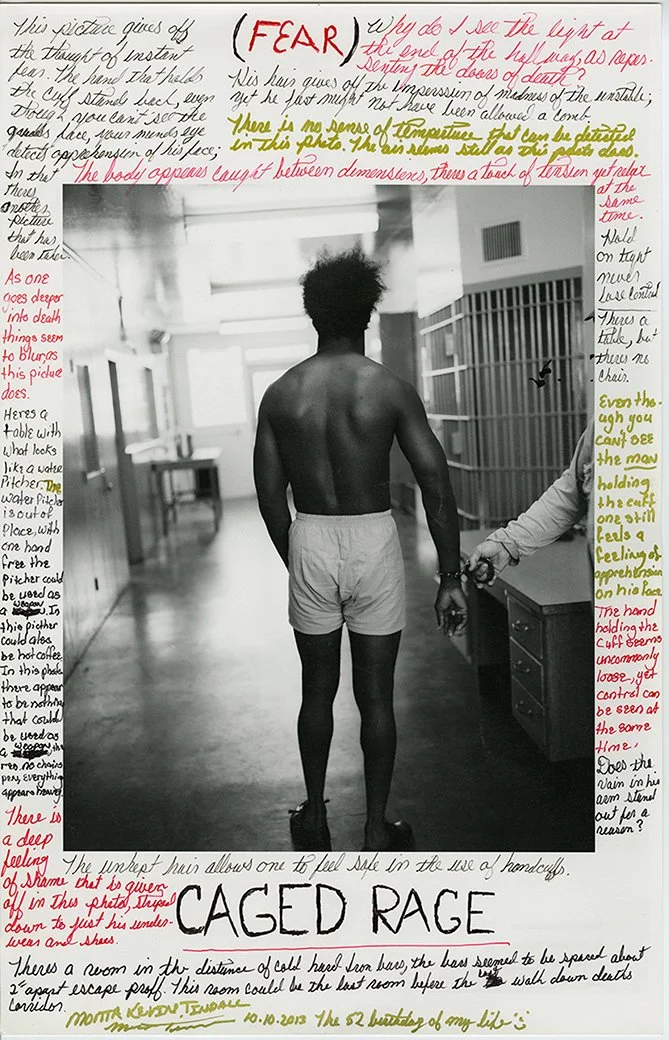

So I got together a group of guys inside San Quentin who were interested in photography, and I got permission to hold like a mini photo class. We met for about a year, a couple times a week, and I was able to bring in images from the archive. We would talk about them, look at them, and then I could make prints of them, and the guys could select images that they wanted to write about.

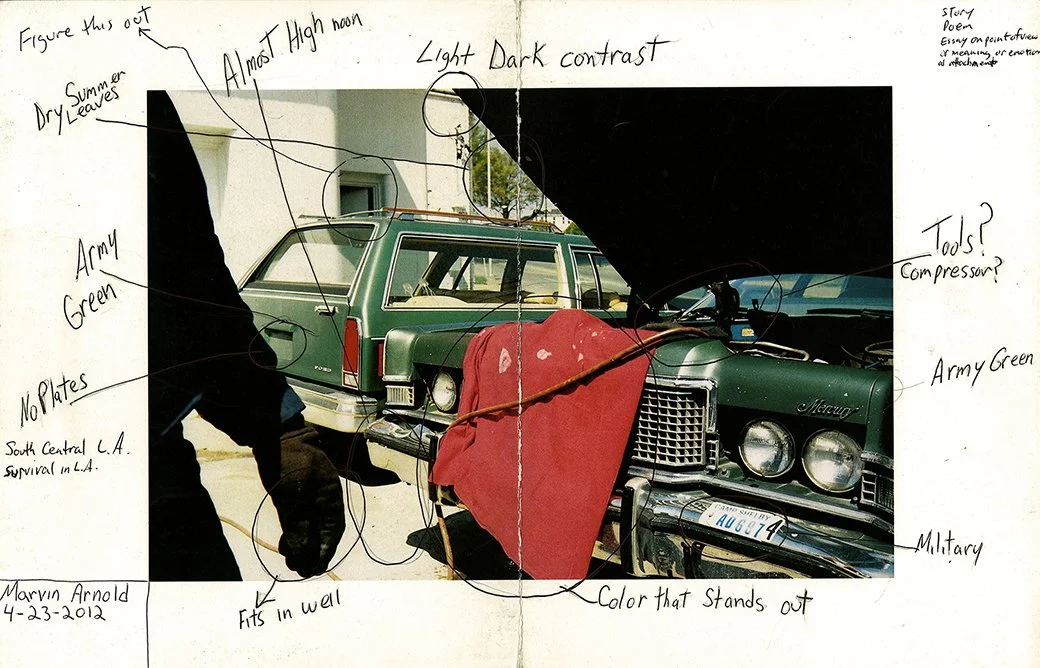

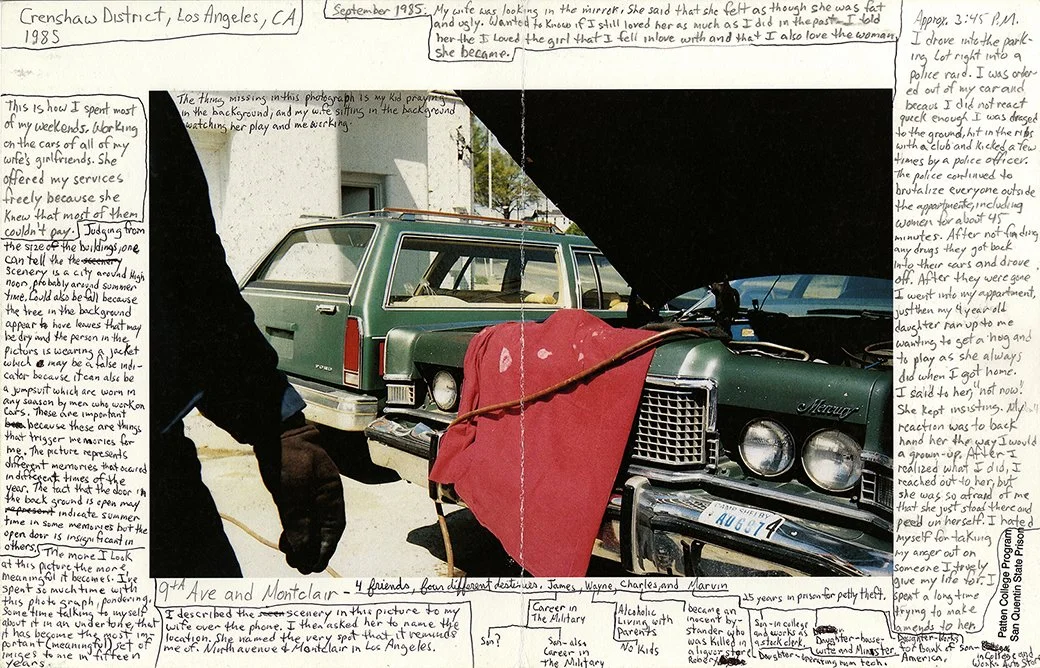

What I did with this was what's called photographic mapping. So I asked the guys—I printed the image on two sides, and I asked the guys to live with the photographs for a while, and on one side, write about them, sort of map them, make note of what stands out to them. Literally write on that image. Don't be afraid to write on the image, circle things, scratch things out. Ask yourself questions, and then take that annotated photograph and your notes and then write a narrative based on your understanding of the photograph.

Because those guys were the people that had experience in prison and knew about that life, they were able to open up those photographs in ways that I would never be able to and to tell stories based on their own experience of being incarcerated. So I'm going to say it tamed the images. It didn't do that, but it gave the images another layer of life. So the first layer was the experience. The second layer was that a correctional officer photographed that experience or documented it. And then the third layer is these people, decades later, are looking at it and interpreting what they see and inserting themselves into the experience. And I'd love to tell you and share the image if you haven't seen it about the one Ruben did, the guy I told you about earlier.

HL: Tell me more about that one.

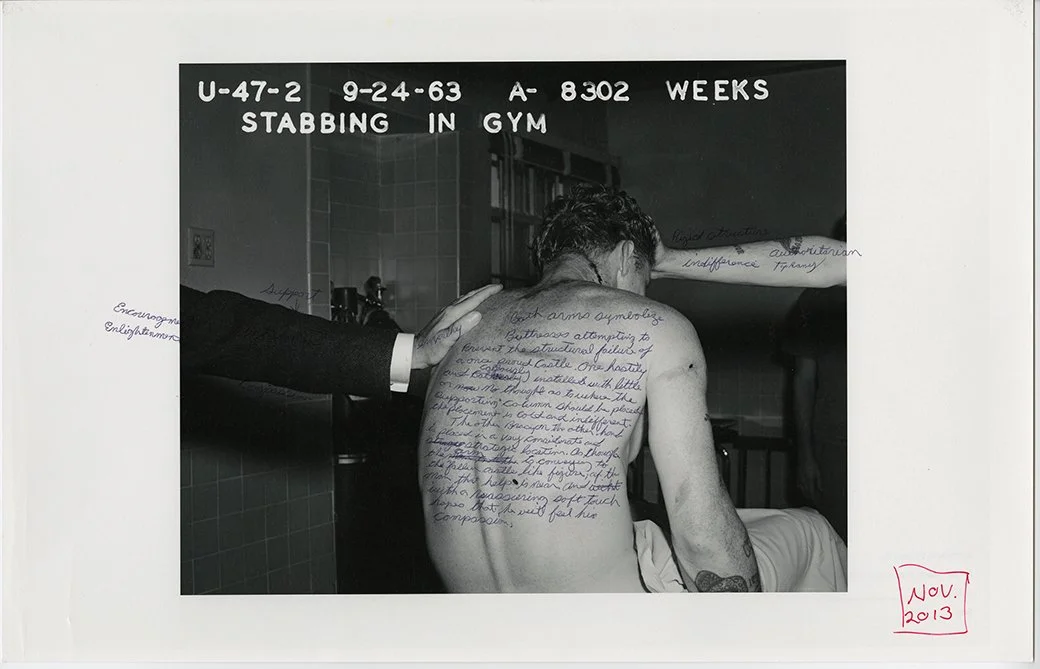

NP: Yeah. So there's an image—and I'll share it with you if you don't have it—of a man who's been stabbed and he's being held up by two arms. You just see him from the back and you can see stab wounds. It's not bloody, but you can see he's been stabbed. And there's one arm holding him up that's bare and has a lot of tattoos. And on the other side there's an arm holding him up that has a suit jacket on.

When I look at that image, it's a scary image of someone who's been attacked. I can't even tell in the photograph if the man is alive or dead. So Ruben, the guy who intimidated me at first in class, selected that image and he wrote about it. He described it—if I can remember all the words—the body as a once-proud castle that was being held up by, buttressed by two forces, one good and one, I think he used the word evil. And it's this body struggling between these two forces, but still being a proud castle trying to come back to that sense of being a proud castle.

And it was such a beautiful and poetic interpretation of what I saw as a violent image. And clearly Ruben was talking about seeing himself as that body that was being pulled between these two forces and ultimately rediscovering that part of himself that he could be proud of. It was astounding. And for me, that experience in seeing what Ruben wrote about those photographs told me that there was a lot there to discover—that more people would find amazing things in these photographs and be able to share something about themselves, whether they are overtly saying "this is about me," or they're doing what Ruben did and sort of being a little more poetic about it and not shouting out, "This is me."

But to somebody who's a sensitive reader could clearly see this was Ruben talking about himself. And I was also so proud of him. And it again was another thing that made me believe that art can matter in situations that are dire and really big things need to happen to make the changes that I'm not capable of. There's still something that art can bring to those situations and at least make change for the people you can touch. It's not going to take down an institution that needs to change, but it can improve the lives of the people that you come in contact with. And I take some satisfaction in that.

HL: It's incredible. I mean, it's profound because from the outside here looking in, you're asking people to question their perceptions, to also question their own ability to develop empathy and put, as you said, put themselves in the position of what was taking place in that photograph. And then it sounds like, I mean, even from the example that you're giving with Ruben—that they start to tap into something that's probably not just in prisoners. Obviously, I have no experience with this, but with all of us as humans, something that's oftentimes repressed is that there's a mask or a facade. And here you're saying to a prisoner, the tough guy prisoner, "the proud castle and its potential of collapse." I mean, that's something truly beautiful.

NP: I love that you used the word empathy because I think that is something I care deeply about. And, you know, I also teach students that aren't in prison, and it's something I talk about a lot with my students—building empathy for yourself and for others. And it's really such an important thing. I notice it with a lot of people, this lack of empathy for themselves. And without being gentle and caring about yourself as well as pushing yourself and examining what's difficult, you can't have empathy for other people. And empathy is such an important characteristic, and it's something that we all need a lot more of now in every area. But yeah, I think leading with empathy and gratitude is really where it's at.

HL: I want to pull on that thread a little bit further. One of the goals of these projects that you've created and collaborated on at San Quentin State Prison is to humanize incarcerated people. And of this you have said, quote, "Basically everything that happens outside prison also goes on inside prisons." When I read that, I'm interpreting it—in effect, love, conflict, heartbreak, humor, banal routine. How did the topic, like choosing a cellmate, become a starting point for your Peabody-winning and two-time Pulitzer Prize-nominated podcast "Ear Hustle"?

NP: Yes. So I will also add that the podcast was created by myself and Earlonne Woods. So I should say it's our podcast, and we started it when he was incarcerated at San Quentin. He's now out. So one of the things we wanted to do—we were so clear with this podcast what we wanted it to be and what we didn't want it to be. And it was not going to be a true crime podcast. It was not going to be about how unjust the system is. It wasn't going to be about violence. It was going to be: how do you make a life when you get to prison? And how can we show commonalities between life inside and life outside? Because again, that's about creating empathy and understanding.

And so everybody has to figure out how to live with other people. It doesn't matter where you are. It doesn't matter how old you are. Everyone has to figure out how to live with another person. Now in prison, you have to figure out how to live with a person in a very small confined area. And so we just thought that would be a great topic to open with because we could tell stories that were difficult, scary, funny, surprising, and people had no experience in prison could relate to that because everybody, as I said, has had to figure out how to live with somebody, whether you're a student or even your family or roommates or a partner. It's something everybody navigates.

And so we've held on to that in our "Ear Hustle" stories—they're not always so clearly connected, like finding a roommate, but often they are. It's definitely a thread that runs through our stories. And it was a great way to introduce the concept of what "Ear Hustle" the podcast was going to be.

HL: The one side that we've been talking through in your art projects, through the photography project, through what you're now starting to hit on here with "Ear Hustle," is this idea of empathy, of living with others, connecting. I want to go to the other side of the coin here, so to speak. In telling prisoner stories, you've noted the idea of being careful about the ethical side of this. You once said, quote, "I'd never want to retraumatize or insult or belittle victims, or have it come across that we're not interested in accountability," end quote. To strike that balance, how do you approach stories on these deeply sensitive subjects, like violent crimes or survivors' perspectives, in a way that's humane but yet it's not dismissive of responsibility?

NP: This is very difficult. So we rarely do stories about people's crimes. Again, we try to keep it about the everyday. But we have done a couple of stories that include crimes, and they've been difficult and fraught for me because the quote you just said—I do care about victims. I care very much about victims, and I do think people need to be accountable. I do think prisons need to exist. And so I try to balance that.

But we make it clear that we aren't journalists. We are storytellers, and we are always looking for that fact and fiction sort of mixed together. And I don't think I'm letting myself off the hook by saying those things. But that is part of what we do and part of what we don't do.

So when we've done—I can give you an example of a story maybe we did about a crime and how we dealt with it, and maybe that will answer the question. We did a story about a man who was a rapist, and he committed a very brutal crime. And we were just talking to him, and I'm not sure about his story—how true all the ins and outs, the truth of his story. And in the narration, I make it pretty clear that I'm not sure what he's saying is the complete truth.

And we wanted to figure out how we could get the other side of his story, and we did a little research, and it turned out the woman that he had raped had died. So there was no way we were going to be able to talk with her, and we didn't want to turn it into this true crime story. But what we did do was we found the woman's sister, and we talked to the sister about loss. Not necessarily about the crime, but what it did to the sister and what it was like to lose the sister because she eventually had died of cancer. So a lot of it was her memories of her sister. We didn't talk that much about the crime, but it was really her memories.

And it was a very hard interview to do. It was on the phone. I didn't meet her in person. And I remember I was so nervous to talk to her. And so we kept all of that in the story—how difficult it was to talk to her or how emotional it was to talk to her, how there were these very awkward moments. And I hope when we do things like that, it's a nod to the complexity of what it's like to tell stories where people have been greatly harmed.

So we've maybe done a handful of stories like that. And I talk to people who have been victims of crimes to get their perspective on things. I answer a lot of emails from people who have questions about the stories that we do. I sometimes think this is odd, but we hear from a lot of people who have been victims of crimes who are very thankful for the stories that we do, which surprises me. And I always say this: I have never been a victim of a violent crime, nor has anyone that I love. And if I did have that experience, I don't know how I would feel about this work. And I say that as a way of acknowledging that until you have that experience, there's no way of knowing how you would react. And so I understand that I'm doing this from the perspective of someone who hasn't had that experience. But I think about it a lot, and I care about it a great deal. And I love to talk to people who have had that experience and hear what they have to say about what we do and what they think we get right, and maybe what we don't get right.

HL: It's really powerful, Nigel. The idea of people who have been victims of crimes writing to you and telling you they appreciate what you're doing—what do you make of that?

NP: I think that people who are able to do a lot of hard work and come to the realization that they don't want their life to be ruled by the terrible thing that happened to them—it's a kind of forgiveness. But I think more than it being a kind of forgiveness, it's a statement of resilience, and that they understand that people are many things. There are some really damaged people out there that are capable of doing horrible things. And there's also people who are capable of change.

And I guess those people who are able to—I'm going to use the word forgive, even though I think that's not quite the right word—they're able to see that and they're able to have some kind of enlightened realization that they want their life back and they can't if the trauma becomes the main focus of their existence. I don't know how they do it. I think it's really difficult. I'm not sure I would be able to.

Obviously trauma is a real thing. There's the memory, there's the body memory, all of that stuff. I'm really impressed with those people who can do it. It's not easy. I mean, I think of the little petty resentments I have at people that I can't let go that are nothing. So I'm amazed when people have these life-altering experiences that they are able to not completely let go of—it's always going to be there—but they're able to somehow get their life back together.

We did another episode about, unfortunately again, it was about rape, with the victim of somebody who had been raped. And it was the story about her, how she's moved on, how she's been able to deal with it. And it's not perfect. She still has a lot of difficulties, but it's an interesting one.

HL: Before "Ear Hustle," before your project with photography at San Quentin State Prison, you experienced what you called a second calling. You unexpectedly received some beautifully illustrated letters from San Quentin that were addressed three times to two different people. When they end up in your hands, in your place, what was your reaction to getting those misdirected prison letters just out of the blue?

NP: Yeah. So, okay. I love communication and I love miscommunication. I just think it's so interesting. It goes back to that fact and fiction thing. And so I'm always looking for the meaning of stuff. That's why I have so much found stuff on my wall. There's always stories there.

So it was a letter that was delivered from San Quentin. I don't remember the person's name. I don't remember their address, but it was not even close to our address. And the first time I thought, "Oh, that's funny." And I remembered I brought it to the house, the right address. I never saw the people. I left it there. It was on South Van Ness. And then it happened a second and third time, and I just delighted in it. I really did feel like there was some—I don't want to sound hokey—there was some message. I don't know if it's a cosmic thing. There was a message that if I paid attention to it, there was something there for me to follow.

And I think that happens for everybody. If you pay attention to those things, I don't know how they happen. But if you keep your eye open for them, they will happen. And that was like one of the few things that happened that got me interested in prisons and particularly San Quentin. Without that letter, I don't think I would have ever gotten to San Quentin—without that misdirected letter.

HL: "Ear Hustle" doesn't happen if someone didn't misdirect the letter.

NP: If the post office didn't make a mistake. And I love the post office, but I'm so glad they made that mistake.

HL: That's beautiful. I want to turn the attention to some of your own artwork and projects. You mentioned there's a turning point in 1990 when you were allowed to photograph corpses being dissected at a medical school, which you said, quote, "changed everything for me. After that, I felt somehow it was okay to use myself as a source and not feel like everything had to come from the outside world," end quote. Can you talk about that experience and how working with something as visceral as a human corpse has influenced the personal intimacy and courage in your later projects?

NP: Yes. Okay, so I will be honest here. I did not have permission. I snuck in, and it's long ago enough that the person who snuck me in wouldn't get in trouble. Because I think you're not supposed to do that. So I was pretty scared to go in and see bodies. And once I started looking, I was so fascinated and I was very respectful and quiet about it. And they were bodies that had been donated for science research.

So what surprised me at first was how they all looked the same, because—I don't know, this is not I hope this isn't too gruesome—they had obviously been dead for a while and preserved, and so everyone had the same tone. Everyone looked like old brown paper that you dry your hands on. You know what I mean? Like sometimes you get this brown paper you dry your hands on. So they all had that tone. There was no blood and viscera, but they had been somewhat dissected so I could see into some of the bodies. The person I was with who was a doctor could lift up different parts so I could look in and see what was inside.

And I was so touched and overwhelmed thinking about how complicated people are inside. Getting to see inside a body, even though there wasn't blood and gore, made me think about the imagination and thinking about the lives that these people may have had. I'll never know who they are. And my pictures, you wouldn't be able to identify anyone anyway. But somehow what was frightening about it disappeared so quickly. And the fascination of looking and looking with compassion took over, and I felt a kind of strength, an inner strength to look at something that's hard—to think about dying, to think about what happens to our bodies, to think about the meaning of life and also feel enlivened by it and wanting to know more about the mysteries of not necessarily the body, but the mysteries of the mind. I think seeing those bodies made me think about the mysteries of the mind.

And I thought, "Well, it's okay to be more interested in your responses and thoughts." Up until that time, I'd always done portraits of other people and sort of more street photography. And I had a teacher at college who I really loved and respected, but he was very dogmatic about the only kind of photography that really mattered was documentary work about the world outside of yourself. And I think that's okay. But I had to eventually move away from that and realize that your interior world, without being solipsistic or navel-gazing, is also a really interesting place to be.

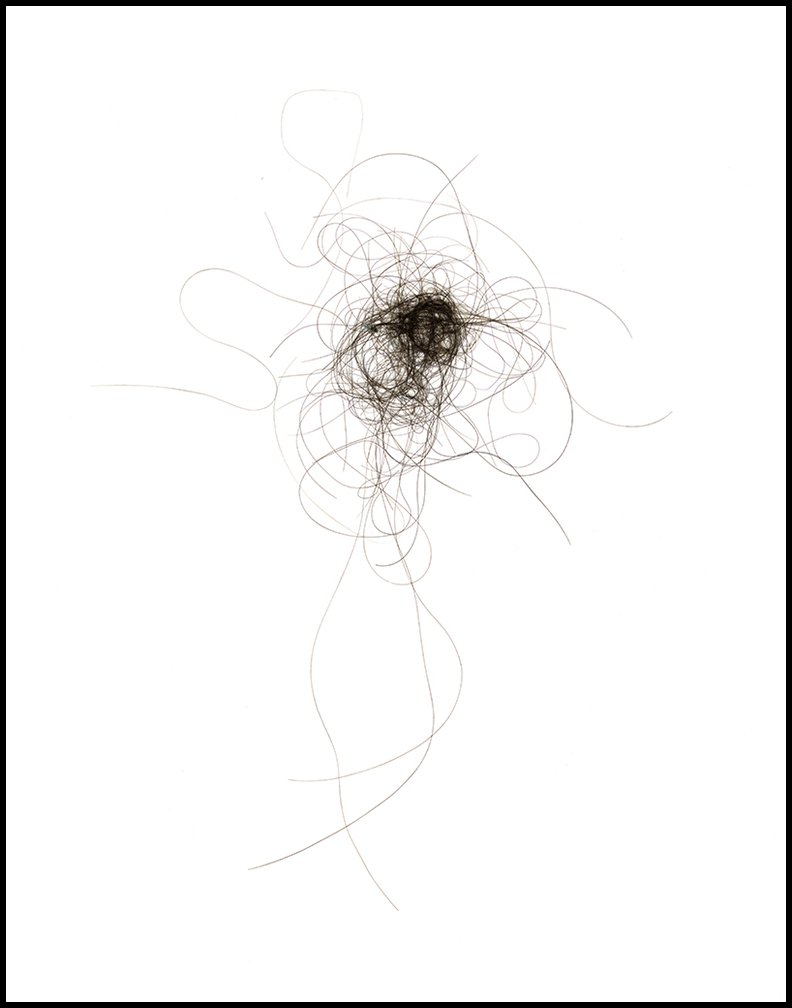

HL: Well, there's a particular project that does this to an incredible degree. It was meticulous, I might even say. It's your project "What Didn't Go Down the Drain." One of these early projects involved saving the hair from your shower every day for a year. As you say, quote, "collected your hair from the drain every day after your shower, put them in little baggies, dated them, pinned them onto your studio wall in chronological order," end quote. What motivated this and what meaning did you pull away from this and find?

NP: Yes. So for a long time, my goal was to get a tenure-track job, and I told myself I would get one before I turned 40. And right before I turned 40, I got hired for a tenure-track job, and I was very excited. But I started to think about how every goal that you attain comes with a side you didn't quite think about. And so the idea was—hair is a representation of things that we think are beautiful. We love hair in certain places. We are worried when it's in other places. And so I thought the idea of losing hair would be a good way to talk about the stress of attaining a goal.

So that was the idea behind it—that every day I would take the hair out of the drain and put it in a bag. I also like thinking about humble materials, everyday materials, things that some people might think are gross, which can actually be quite beautiful. And hair is certainly that. And I love to pull things out of drains. Like my dream would be to come to someone's house and clean out their shower. It's amazing what comes out of there. And so just pulling the hair out—it's a little bit gross, but I also just sort of enjoy it.

So that was the idea—to think about humble material, think about material that's gross but can be beautiful, think about a way to track meeting a goal and then investigating the parts of that goal that are not exactly what you thought they would be. And I love committing to long-term projects. I think it's really—I love the meditative sort of aspect of that, of doing a repetitive action, like pulling the hair out of the drain, drying it and putting it on the wall and having to do it. I did it for an academic year. And then when it's over, that part is over. Then I figure out how to make it visual. But I like the discipline of that—of repetitive goals and time-based projects.

HL: I remember one of the images I came across from your photography project at San Quentin, where you had prisoners describing something, and in the margin someone had written—and it was something I hadn't even considered. So you're looking at a car and the hood of the car is open and you see, you know, like an oil rag or something sitting there, and someone is describing what time of day it likely is based on looking at this engine because of the placement of the sun and the shadows cast. I thought, "Wow, that is really fascinating." And it goes back to the guy that you were saying earlier—that this class changed his perspective in day-to-day life, that he's walking down the street and starting to see life differently.

NP: Yes, that's what I mean. I'm sure other arts do it, but that is one thing that photography does—it really trains us to look carefully and to see those clues, like exactly what you're saying, trying to figure out the time of day by the light that's on the engine. That's so cool. It gives—when you can do that, when you can start to dissect things and find those clues—it also gives you, and this is when I think about my students, a sense of self-esteem, because you are connecting with your own creativity and your own creative power. And that's amazing. That can be life-altering. Even if you don't become a well-known artist, that doesn't matter. It's knowing that you're creative and that your mind can take you on these journeys. I love that, and that never disappoints me. And when I see that light in somebody, it's great.

HL: The personal aspect that we're hitting on here with your work—I mean, using your own hair as a medium and talking about these ways—even what you said, I don't think many people would, even if they shared that sentiment, I don't know that many people would say, like, "I love pulling things out of drains." You know, it's like you missed your career as a plumber, Nigel.

NP: Totally. Yes, totally.

HL: There's a quote where you talk about this internal contradiction—you have this very public, very vulnerable, very personal element, but you say, quote, "I'm a fairly private person. I'm shy. So this self-exposure portrays yet another personal contradiction," end quote. What have you learned about yourself by being so vulnerable through your artwork?

NP: Well, first of all, I love contradictions. I think people are the most interesting in their contradictions. And I am a shy person. But I think—and, you know, self-conscious, just like everybody else. But the older I get? Let's see, how do I say this? I realized, you know, all we really have is our imagination and our ability to see things. And if we can't delight in that, there's a problem. Our life is kind of gray.

And I'm dyslexic. And when I was younger, you know, school was really hard for me. And at the time when I was growing up, there wasn't a lot of help for people who were dyslexic. And so I always had to find workarounds to learn things that I think other people learned pretty easily. And for a long time I was, you know, probably ashamed of that. I don't know if I was ashamed of it. It was curious to me. And then I realized at some point that's actually a strength—to be able to find a workaround. And I think that's what's really fed my creative life.

That's not answering your question about not being private. I think what I try to do, humbly, when I'm a public person is let other people know that you can do more than you think you can do.

Continue

6:43 PM

If you're a shy person, you can retrain yourself, if you don't want to be a shy person, to be more out in the world in the way that works for you. So I always, I guess I'm always going back to wanting people to feel more empathy for themselves, more understanding of themselves, and take hold of their life and realize you've got this short period of time—you need to make the most of it. You need to figure out what you want, what you can contribute, and how you can make your everyday life interesting.

And I've also always been somebody who's aware that time is quite limited. I remember always thinking I was old. Now that I am old, I wish I hadn't always thought that way, but I am aware there isn't a lot of time. And so I always think about how do I want to use my time. And I like to instill that in other people—that you've got to use your time, you've got to take advantage of it. You've got to be strong and not have regrets.

So I think some of that being a public person is about that too, or having, you know, being more extroverted. And the other thing is, as a teacher, as an educator, I give a lot of lectures, and I believe part of being a teacher is leading by example, but also it's not a performance. But you have to hold people's attention. You have to invite them into this excitement you have about a subject. And the way you can do that is by—it's not a performer, but you have to hold people's attention. And I learned a lot of that through teaching and public speaking. But, you know, when I go to a party, I'm one of the quieter people at the party, but if I'm giving a talk or a lecture, you know, I think I become a slightly different person.

HL: I want to pull our conversation full circle here with a couple more questions. One that really extends on what you are just mentioning right here—you're at the party, you're kind of the quiet person. In 2021, you and your collaborator Earlonne turned your podcast into a book.

NP: Oh yes.

HL: This is "Ear Hustle: Unflinching Stories of Everyday Prison Life." So how did it feel to write about yourself and Earlonne, essentially these memoir portions of the book, after keeping that mostly out of the podcast?

NP: I'm glad you said that. We are pretty intentional about keeping personal stuff out of the podcast. Now, of course, it comes out because you hear our opinions of things, but we don't talk about biographical stuff. So it was a little strange to do. Earlonne doesn't have a problem with it. And so we, you know, we wrote the book together during COVID and it needed to be—we needed to be like partners in it. And so when I saw how easy it was for him to do, I was like, "Okay, I'm going to do it too." So I think we encouraged each other. Left to my own devices, if I was doing it on my own, I think it might have been harder.

And that's a small part of the book, but I think it ended up being okay. At first I was a little bit nervous about it because I didn't know what people would think. But I think again, because Earlonne was happy to do it, it made me a little bit happier. And we found out things about each other, which was nice too. So that made the process a little bit easier. Yeah.

HL: Well, you've mentioned Earlonne a handful of times through our conversation here today, and when you do, you light up. And there's something beautiful about that because you have this long-running, collaborative creative partnership that the two of you have done with "Ear Hustle." And, you know, I've listened to your podcasts, I've heard his voice, I've heard some of his story. But taking all of that, who is Earlonne to you personally?

NP: Yeah. Okay, so I met Earlonne in 2012 at San Quentin in the Media Lab, which is—San Quentin has a media lab, and it's where I started volunteering after I was teaching. So there's a newspaper there. We started a radio program. There's a film project there, and ultimately the podcast. There are a lot of men down there that are sort of boastful and talk a lot. And Earlonne was the quiet guy there who was just always present. And whenever there was a problem, he would take care of it. And I'm always kind of interested in the quiet person in the room because I want to know more about them. So I was just drawn to him because he was quiet.

We got to know each other. We were working on a radio project together and it just started to go south a little bit. And I had been volunteering at San Quentin for quite a while, and I was thinking, "Maybe this isn't what I want to do. Maybe I need to be thinking about something else." And so I talked to Earlonne about it, that I was having problems. And he said to me, "Give me 90 days and we'll change things." And in 90 days, we came up with the idea of the podcast, and we broke off from the radio group and started our own thing, and we created something out of nothing.

And I'd never collaborated with someone before. I'd always been a very solo person, and I loved alone time in my studio. But something about our personalities just clicked, and it started because he was quiet. It started because he said, "I'm going to solve this problem." And he did. And together we did solve it. But without him, it would never have been solved. And so we're very unlikely. We come from very different places. We have very few shared experiences. But yet together we created something that had never been done before. And I met somebody, Earlonne, who worked as hard as I worked, who was willing to put his heart and soul into something that he didn't know would go anywhere.

And the experience of creating this podcast in a very unlikely place, in a place where people said, "There's no way you can do this"—we just quietly put our heads down and created something, and that bonded us, an absolute bond. So now it's 2025. So I've known him—is that 13 years? And we've been through a lot together, you know, starting the podcast, him getting out of prison, him deciding if he wanted to keep doing the podcast. He'd been inside for—I think he'd served a total of 25 years. When he got out, I didn't know if he'd want to continue to do stuff about prison. He did. He said, "We wrote this book together. We've traveled around the world together. We give a lot of talks together. We continue to do the podcast. We're co-hosts."

There's some inexplicable connection. But yeah, I mean, when I think about him, like, you know, I smile. I mean, we're partners. We also fight, you know, but we're great working partners. And we understand—I think this is what really makes it work—we understand each other's strengths and weaknesses, and we know how to support that. We barely need to talk. Like he knows that I get so frustrated with technical stuff, and I think that goes back to my dyslexia. I can really—he knows when I'm about to lose my temper. And he's terrible with time and scheduling. I'm great at that. So that's just like a good example of I can take care of that stuff. He'll take care of the technical stuff. We mesh on mic. Like a lot of what we do is improv. So she's just like—I guess we call each other ride or die. We're ride or die partners.

HL: I love it. So, you know, as a final question here, I'd like to hear your thoughts on a sort of subjunctive future or maybe something that you would like to see or what you think with all of your experiences that we as the outsider, so to speak here, could see and understand. So your exhibition, "San Quentin Prison Report," it was noted for, quote, "facilitating a dialogue around how we manage crime, punishment, and rehabilitation in the United States," end quote. What kind of conversations or changes do you aspire to spark in society by bringing these prison narratives to light?

NP: Yeah. So what I would like people to think about is who is in prison and what kind of sentences are we giving people and what can prisons actually be? Again, I think prisons need to exist. I don't think they need to exist in the way that they do. I think they really need to be more educational spaces. They need to be places where people, yes, pay for their crimes, but they're growing while they're doing that. They're learning. They're going to come back to society and be, you know, productive societal component, I guess, is what I'm trying to say.

And so I wish we would just look at how prisons function. San Quentin is an interesting example. There are so many programs that happen in there. They're mostly run by volunteers, which, you know, it can be a problem, but because of that, it's an exciting place to be. You know, I mean, these people are still suffering. It's not like it's cushy, but people's minds are being expanded and they're growing just like students are at a university. And education is just really important. So that's what I would like to see happen.

Of course, I would like to see some sentence reform. I mean, I think the sentences people get here are crazy. You know, the three strikes law, things like that, which everyone is really involved in. And so I guess I would like to see—we went to Norway early on, and I know Norwegian prisons are famous for being places of rehabilitation. People that work in prisons in Norway have college degrees, and a lot of them are counselors. That would be amazing. That would be very expensive. It'd be hard to do here. But changing that mindset about why people work in prison and what they are trying to achieve is important. It's a huge lift. I don't know if it's going to happen in my lifetime, but I can see little changes happening.

And just if more people knew what happened in prison, more people would want reform to happen. And, you know, the other thing I've learned from doing this is I had no idea how many of my students at Sacramento State had incarceration in their family or some experience with it. You start to realize it's way more common than you think for people like me who didn't grow up with it in my family. So I think if we could just lower the wall that way, it would be helpful. Again, I'm not saying let people off the hook at all. Not saying that. But there are reforms that make sense to me. I'm not a politician. I'm not good with numbers and laws, but, you know, that's my two cents.

HL: The "proud castle" idea is really sticking with me, and, you know, as you were speaking during our conversation today, I keep getting that visual of the fiction and the fantasy, the nonfiction and this interplay, particularly as it relates to the guy telling you, "I was a baby in the crib looking up at my mother. And I don't know if that's what really happened, but it's what I want to have happened." Because it really speaks to that one thing that we all share is a deep desire for approval and love and acceptance. Nigel Poor, thank you so much.

NP: Oh, thank you, Hugh. It was really fun. Appreciate it.