Ken Feingold, The Animal, Vegetable, Mineralness of Everything

Art in Context

By Hugh Leeman

While Artificial Intelligence is an umbrella term for a multitude of technologies that have been researched in labs for decades, most of society first became familiar with AI through consumer-facing large language models (LLMs), like ChatGPT.

In 2022, OpenAI released ChatGPT to the public. Within months, it became shorthand for ‘AI’ in mainstream media, reaching 100 million users in two months and becoming a mainstream tool on phones and computers. At the start of 2026, ChatGPT and similar LLMs like Claude and Gemini are estimated to be used by more than 1 billion people. LLMs are trained on phenomenal amounts of data, from articles and emails to published books and online forums, allowing the model to generate and analyze text.

Wendy Hiller as Eliza Doolittle and Leslie Howard as Henry Higgins in the 1938 film version of George Bernard Shaw's Pygmalion.

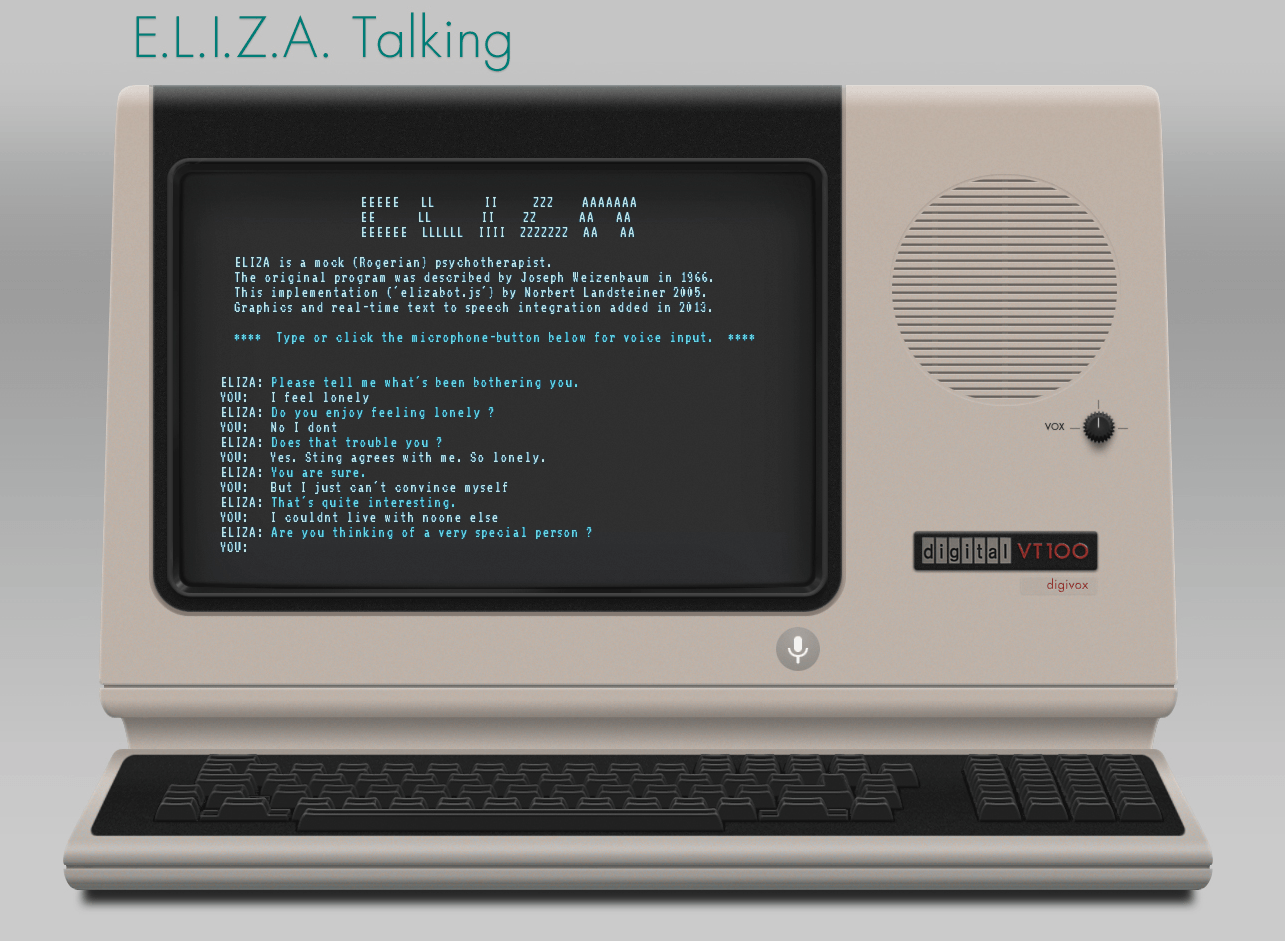

Language Models have been studied and experimented with, albeit in a rudimentary form, since the 1960s, when MIT computer scientist Joseph Weizenbaum created ELIZA. The early language model was named after Eliza Doolittle, a fictional character in George Bernard Shaw's play Pygmalion, written in 1912. In the British play, Eliza quickly loses her Cockney working-class accent and, with the help of Henry Higgins, a phonetics professor, refines her speech to blend in with upper-class society. Eventually, Eliza rejects Higgins, who treats her as an object, and asserts her independence.

Wizenbaum programmed ELIZA to interact with human users as a psychotherapist would a patient, asking open-ended questions to encourage self-disclosure, which the program could reuse to continue the exchange. While Eliza was a far cry from today's LLMs like ChatGPT, it served as a signpost into the digital jungle of machines, taking steps towards the threshold of the profound feature of human intelligence: complex linguistic capabilities.

Between ELIZA in the 1960s and today's language models, artist Ken Feingold in the 1990s began experimenting with language models prognosticating through his artwork The Animal, Vegetable, Mineralness of Everything, on the potential impacts of AI if the technology were widely adopted by mainstream society.

The artist with The Animal, Vegetable, Mineralness of Everything

The piece, which first showed in 2003 at the Shrewsbury Museum and Art Gallery in Shropshire, United Kingdom, before touring the United States, used three life-sized silicone self-portraits that "debate the nature of violence with each other, and discuss their fears – generally their fears about each other." Each head takes on a persona representing a different realm of existence; one speaks for the animals, another for the vegetables, and yet another for the minerals.

Feingold created the software that empowered the silicone heads to speak while their faces animated the exchange. The conversations are always unique. The artist writes that "each has its own personality, a vocabulary, associative habits, obsessions, and other peculiarities, which make their conversations quirky, surprising, and often hilarious. They challenge our understandings of our relationship with emerging forms of artificial life."

Looking at the artwork, if you are wondering about the black-and-white object just beyond the heads, you are in good company, as the heads, too, are fixated on what it might be. Viewers witness unscripted conversations between the heads as they "wonder about 'that thing' before them, and we hear how they project their own interior worlds onto it in an attempt to figure out what it really is."

They, like we humans, are meaning-making machines, capable of projecting their fears and desires onto the unknown to make sense of the world.

In a transcript published on Feingold’s site, the discussion waxes philosophical:

Animal: Minerals are so hard. Minerals don't care about us at all.

Mineral: We are the basic material of everything.

Animal: Is struggling for survival a kind of violence, or not?

Vegetable: Animals are so violent, all of them.

Mineral: Animals make war.

Animal: We are the only ones who really think, so we have the right to do whatever we please.

Feingold writes that "Although the heads hear each other, nothing seems to penetrate or influence their ideas; no matter what the subject matter discussed, they eventually return to their own interests and fixed ideas." In this, we see a reflection of today's information silos of the internet.

Today, the internet's information silos, particularly AI-governed algorithms of social media and Google searches, illustrate how we humans are drawn to information that best agrees with our preexisting beliefs, reinforcing opinions until they feel like facts. This is exemplified by information largely influenced by a single point of view, incapable of integrating nuance into the dialogue; any information that is an outlier is not to be considered; instead, it is just wrong, reducing society's beliefs and thoughts to an oversimplified discord. The black-and-white of the curious object evokes the binary of such social discord, devoid of the near-infinite spectrum of nuanced grayscale that occurs between extremes.

As the same conversation from the transcript above carries on between the heads, it devolves into antagonistic accusations:

Vegetable: Animals are the most violent of all – everything you do hurts us.

Animal: We are the ones with technology to make things better.

Mineral: You have no technology beyond smoke and mirrors.

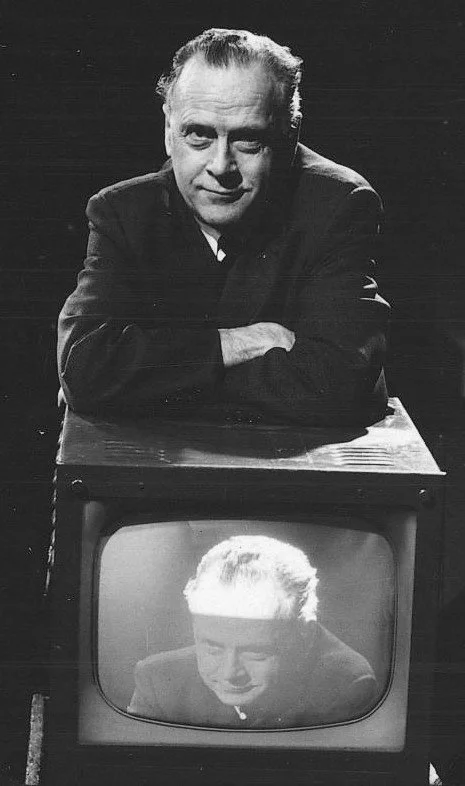

Marshall McLuhan with a television showing his own image, 1967

Feingold's piece made at the start of the 21st century could well be a testament to the often cited 20th century Canadian media theorist Marshall McLuhan, who once said, "I think of art, at its most significant, as a DEW line, a Distant Early Warning system that can always be relied on to tell the old culture what is beginning to happen to it. Art acts as an early distant warning system, warning the old culture about the psychic and social targets so that we may have plenty of time to prepare for change."

With more than two decades of hindsight, Feingold’s work was the Distant Early Warning system warning us about the psychic and social targets, yet the smoke and mirrors of technology now subsume a society unprepared for change.

Today it would be naive to believe that we like George Bernard Shaw's character Eliza, will assert our independence from these systems as amid the smoke that clouds our house of mirrors, what remains clear is humans most precious resource, language and its ability to form connection that enable collaboration upon which culture is constructed is no longer solely in human hands, now it sits in AI's "black box" which no one entirely understands. Yet, it has enough access to our ideas to control our attention and silo our information, leaving humans to question if truly "We are the ones with technology" while pondering the nuance of its ability "to make things better."