Judith Schaechter, Super/Natural, Museum of Craft and Design

Citing influences as varied as botanical illustration, medieval manuscripts, and MAD magazine, Judith Schaechter creates stained-glass panels that are richly layered, defiantly decorative, and a tad perverse (in the best possible way). From Schaechter’s prodigious body of work, seven backlit panels and an eight-foot-tall stained-glass dome are on view at the Museum of Craft and Design through February 8, 2026.

Working in a tradition that got off the ground in the 12th century—with the construction of the Gothic Basilica of Saint-Denis under the auspices of Abbot Suger—Schaechter brings a secular, punk approach to the art form while sharing the Abbot’s faith in the power of colored glass to transfix and uplift the viewer. “Stained glass bathes your body in colored light; it’s a moving experience,” says Schaechter, referring to the phenomenon Suger described as “lux continua,” or divine light. “I believe we have a biological response to radiant colored light, in a way that feels lofty and spiritual,” she adds. “Maybe we’re primed by our experiences in churches, synagogues, mosques—But you know, people stick Skyy vodka bottles in their kitchen windows just to bask in that magical blue light.”

Schaechter has been making stained glass since the 1980s. Although she attended RISD as an aspiring painter, she switched to glass after taking a class from Ursula Huth, a student of Hans Gottfried von Stockhausen, who pioneered the idea of the autonomous panel—basically a stained-glass window that is seen and appreciated as a painting, rather than as a part of architecture. Schaechter felt an immediate affinity with the glass department, in part because of their embrace of ornamentation. “In the painting department, when they wanted to make you cry during a critique, they would call your work ‘decorative,’” says Schaechter, a self-described “militant ornamentalist,” a term she attributes to her friend and fellow artist, Adam Wallacavage.

Schaechter’s pieces teem with ornate and intricate patterns of botanicals, birds, and insects, most of which are derived from her imagination rather than nature (although she credits both Audubon and the 17th-century scientific illustrator Maria Sibylla Merian as inspirations). “I’m a staunch proponent of the ‘more is more aesthetic,’” she declares. Hearing Schaechter describe the hours (and pleasure) she takes in rendering her otherworldly motifs, one imagines modernist architect and polemicist Adolf Loos spinning in his grave like a rotisserie chicken. As Loos opined in “Ornament and Crime,” his 1908 essay, “Freedom from ornament is a sign of spiritual strength.” And also, “Anyone who goes to the Ninth Symphony and then sits down and designs a wallpaper pattern is either a confidence trickster or a degenerate.” Although Schaechter appears to be neither, she is currently designing a moth-patterned wallpaper for an elevator in a prominent museum of American art (whose name cannot yet be made public).

Schaechter, a chronic doodler, has a massive archive of sketches that she pores over when envisioning a new piece. Using Photoshop to play with scale and composition, she makes a black-and-white cartoon and then transfers the outlines to hand-blown, color-coated flash glass while sitting at a light table. Tone, texture, and shading are achieved through a painstaking process of sandblasting, engraving, and rubbing away the surface of the glass with a diamond file. “Ultimately, it’s not a painting technique, it’s a carving technique—like making a cameo,” says Schaechter, “and just as unforgiving.” Working with just red and blue flash glass, black and transparent fuchsia enamel, and a silver stain that creates a yellow tone in the kiln, Schaechter is able to summon the array of jewel-toned hues that characterize her exquisitely embellished work.

At the same time, Schaechter’s figurative compositions are not “merely” beautiful, in the manner of, say, an Art Nouveau stained glass window of wisteria and weeping willows. Her glowing, kaleidoscopic worlds have an undertone of darkness. Many are populated with plucky female protagonists who have been placed in prickly and precarious situations—like gamines and urchins who have wandered out of a tale by the Brothers Grimm or Edward Gorey and into a William Morris tapestry. In the manner of saints and martyrs, they wear enigmatic expressions that can be read as ecstasy, despair, amusement, ennui, pain, melancholy, fear—or some combination thereof. “I think for something to transcend mere prettiness and enter into the realm of the beautiful, there has to be a dose of anxiety,” asserts Schaechter, when asked about the often macabre and darkly funny nature of her work. In the show at MCD, for example, one woman sits under a starry sky amidst a circle of serpents, another cradles a dead unicorn, and yet another is being puked on by a bird.

Although it can be tempting to conflate the artist with her subjects, Schaechter insists she thinks of these figures as dolls that she can manipulate rather than self-portraits. Nonetheless, her younger self might have found a berth in some of the work. “I grew up this sad, depressed little atheist marching around my staunchly Irish Catholic neighborhood, with people demanding: ‘How can you possibly be moral if there isn’t a God?’ Like, that’s a lot to put on a kid! And I also remember thinking that they had a way to seek comfort from despair through prayer, which we didn’t,” says Schaechter. “I had to find it a different way.”

Schaechter’s panels braid together allusions to religion, art history, mythology, and popular culture in a way that sparks multiple paths of interpretation—by design. “I love that people project stories onto my work,” says Schaechter, who shares her own free-associative spins on her blog, Late Breaking Gnus. In My One Desire (2007), a crowned, emaciated woman with a mournful expression cradles a dead unicorn in classic Pietà pose, framed by the rose windows found in Gothic cathedrals. The unicorn, a symbol of Christ (and reputedly visible only to virgins), evokes Hunt of the Unicorn, the late-Gothic tapestries with exuberant floral backgrounds on display in the Met Cloisters. The piece also rescues the once-majestic creature from the “icky” realm of kitsch, as Schaechter puts it, where it has more recently been marooned.

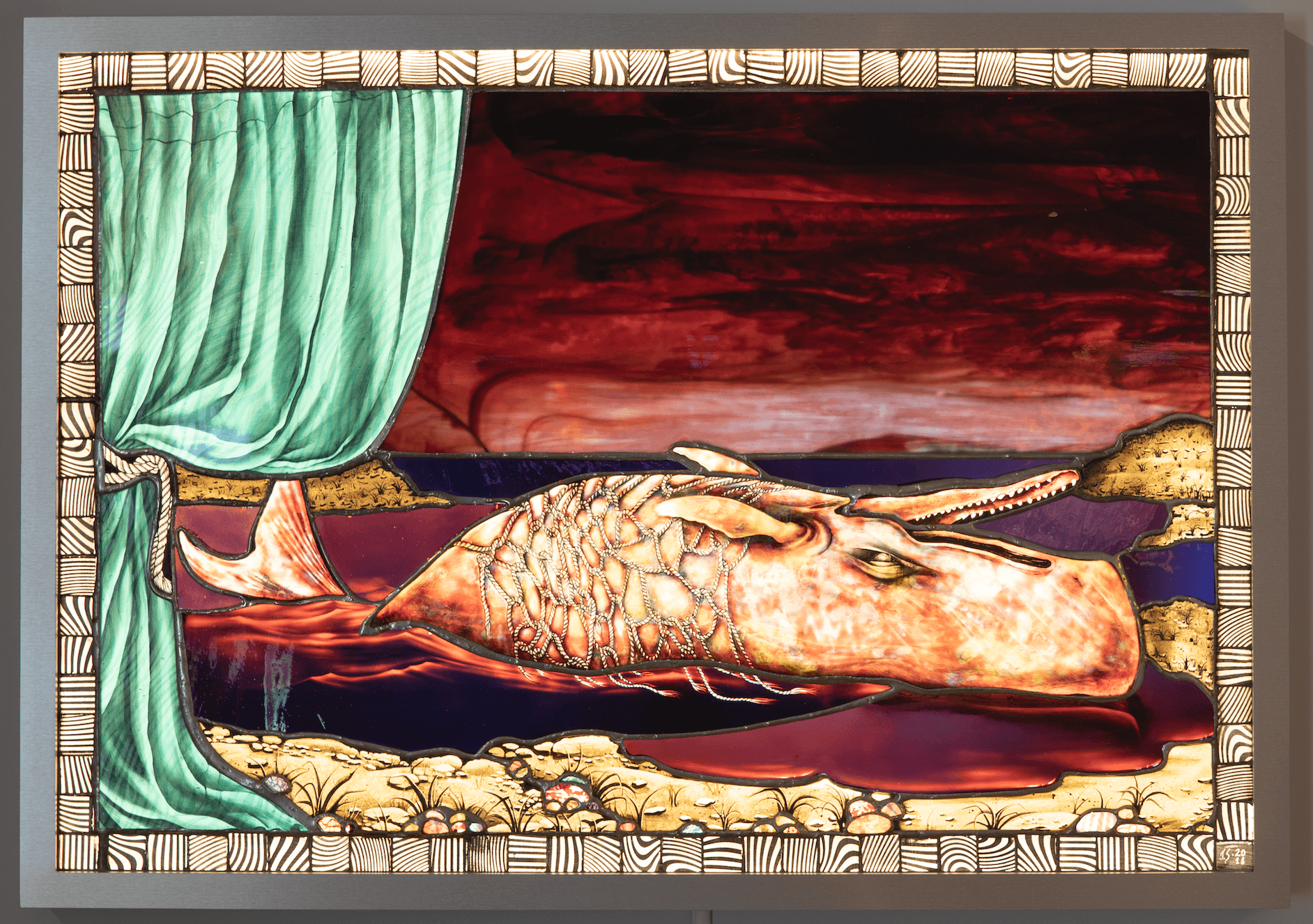

The plight of animals is made overt in Beached Whale (2018), which depicts a sperm whale caught in a net and bleeding into a puddle. “It’s hard to stomach the hubris of killing these creatures and letting them go extinct—he’s literally an animal martyr to our own stupidity,” says Schaechter (who shares that she “stole” the shoreline landscape from a Martin Johnson Heade painting of a thunderstorm). Schaechter imagines the shower of “post-Renaissance” flowers being vomited by a bluebird onto a girl with parted thighs in Efflorescence (2019) as a scene of annunciation—it also nods to Titian’s Danaë, a painting in which Zeus impregnates the princess with a shower of gold. (On the other hand, the bossy bird might also have migrated from Disney’s anodyne version of Cinderella into Schaechter’s pictorial, with the maiden attempting to dodge the floral assault as well as the prescribed happy ending and implicit impregnation.) Wresting beauty from tragedy, Schaechter’s ghostly, double-exposed portraits in Passengers (2022), set like medallions against green mosaic-like tiles, were inspired by the disappearance of Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 in 2014: “I was just imagining what it might be like beneath the surface of the ocean, seeing these faces gazing out the windows,” she says.

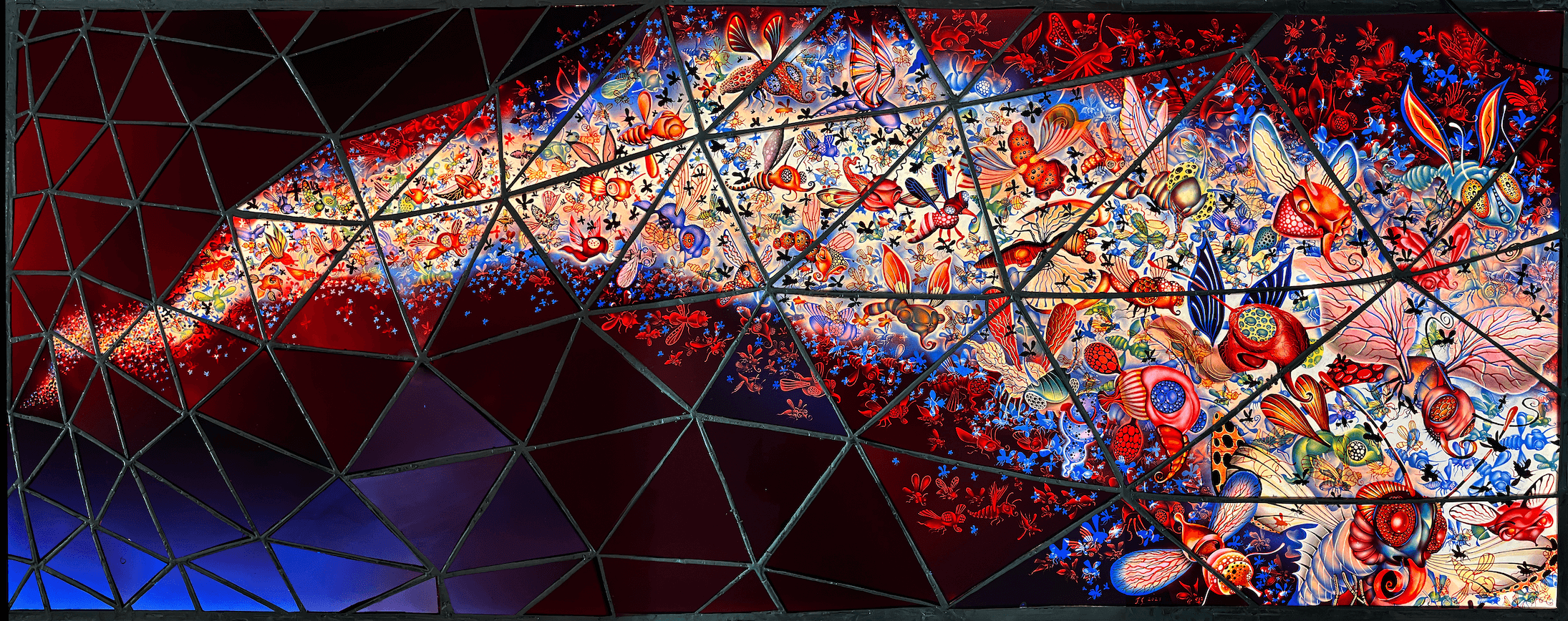

The exhibition Super/Natural shares its name with an immersive stained-glass dome that Schaechter conceived during a two-year artist residency at the Penn Center for Neuroaesthetics, which explores the ways in which our brain responds to art, beauty, music, and nature. At Penn, Schaechter attended lab meetings (led by Anjan Chatterjee, author of The Aesthetic Brain: How We Evolved to Desire Beauty and Enjoy Art) and had free creative rein. “They were doing a lot of research on biophilic design and architecture and the connections between the built environment, nature, and wellness,” says Schaechter, who was moved to design a sanctuary-like space where one might feel surrounded by the natural world. “Super/Natural is a three-tiered cosmos that expresses the idea of biophilia—the human tendency to connect with nature,” she explains. “The architectural aspects of the dome came from thinking about churches, which is kind of an occupational hazard of working in the medium,” she adds with a laugh.

Standing beneath the canopy of birds, stars, and sky and surrounded by insects, animals, plants, and flowers, one experiences something like the stained-glass version of forest bathing—you can sense your heart rate slowing and anxiety fading, even if temporarily. “It comes as no surprise that reconnecting with nature is calming, healing, even transcendent,” says Schaechter, who considers herself a spiritual person, without really knowing what that means. “I’ve read studies saying that people who are religious or otherwise spiritual are happier. And I think, hmm, that’s interesting. I’m not religious and have no intention of ever being so. But I do have a strong sense of beauty and creativity and a feeling of connectedness—not just to other people, but to animals, plants, and the planet. So, yeah, maybe that is my religion.”