Water Futures, TIAT Place (The Intersection of Art and Technology)

Water Futures closed in San Francisco on January 25, 2026, following its Detroit presentation, with organizers exploring a future presentation in another city.

By Hugh Leeman

At the intersection of art, technology, and social justice, UC Berkeley professor and artist Greg Niemeyer curated Water Futures. The group show offered a panoramic view of what the future of water is and could become, featuring 22 artists whose work ranges from water's calming sounds and light-bending effects to the dark realities of water scarcity in Oaxaca, Mexico; rural Kenya, and beyond through photographs, video, and multimedia installations.

Beyond the artworks’ focus on water, the scope of the exhibition and its programming offer a welcome counterbalance to an art world searching for relevance amidst profound societal change. Niemeyer told me, "This is an exhibition of community creating art rather than art seeking community, you can talk with people and learn things and establish collaborative ideas for the future."

The gallery, TIAT Place (The Intersection of Art and Technology), is a pop-up space run by Ash Herr, who built a community by bringing creative technologists together for art salons. Her space is in one of the many vacant retail stores in San Francisco's once-vibrant Powell/Market corridor. TIAT Place has generated a much-needed boost of creativity and, perhaps more importantly, conversation through robust programming. The gallery is supported by a grant from the Svanne family, which supports downtown vacancy activation to encourage creatives to transform dormant spaces into places that attract people back to San Francisco's city center.

For Niemeyer Water Futures, programming was not a peripheral add-on to the exhibition artworks instead, it was a central component that brought in speakers like Jenny Rempel, a postdoc at UC Berkeley and board member of Community Water Center, to speak about community activism around access to drinking water for migrant agricultural laborers in California's Central Valley and California's precarious water supplies. Speakers like Luiz Barata, a senior planner for the Port of San Francisco, spoke on the rising sea levels’ impact on San Francisco and the $13.5 Billion proposal to build a seawall on the city's Embarcadero.

In addition to curating the show, Niemeyer had artwork in the exhibition. He told me the exhibit's goal is, "Collaborative meaning-making rather than competitive dealing, competition can be positive as it can produce great outcomes, but we've seen a lot of that, and now we need an alternative." Niemeyer told me this in the context of society as a whole, but expanded that focus equally onto the traditional commercial gallery model, noting that at TIAT Place, there is no such focus on transaction. Traditional art gallery models are transactional, he said, and have long produced adversarial relationships in which artists compete to make work that sells. At the same time, buyers seek to buy work of “value.” The gallery competes to find the “right” buyer, while the “right" buyers are coveted by other galleries, creating competition between the gallerists. That, he added, is less about producing cultural value and more about manufacturing financial value.

A similar contrast plays out on a grand scale in standout work from artist Sin Sombras (Without Shadows), a Mexican artist from Oaxaca, whose photography and short film in the exhibition shine a light on communal land rights as major corporations produce financial value through resource extraction in her native Oaxaca, one of Mexico's poorest states. The artist's photographs highlight the beautiful, dramatic topography of the region, yet hidden in plain sight is the darker reality: extractive mining for minerals and sand extraction from rivers for concrete production that can permanently damage the river ecology, ultimately impacting people who for centuries have depended on the river as a food source.

In the artist's short film Naishisaa, or water in Oaxaca's native Zapoteco language, shots of Christian and indigenous traditions intermingle and fade as a visual metaphor questioning what passes from one generation to the next, alongside the river that has sustained humans for millennia. Today, these traditions and their people face displacement and conquest through hydrocolonialism, the political control, privatization, and resource extraction that affects communities around the world.

The dynamic complexity of these challenges plays out most poignantly in the banality of daily life as we see a man ride off through a small village on his motorbike. The artist told me this is one of her family members who, like many others, works for the mining company and feels trapped between preservation of the past and the economic necessity that pushes many to participate in the destructive mining practices that have left Oaxaqueños with few options as they witness an exchange of land rights and clean water for financial opportunity.

The video is set against Sin Sombra's soft voice, "Los rasgos (features), only the traces on the earth, on our land remains of what once was…I am reminded of the importance of keeping our traditions alive. But what traditions if we value material wealth over the richness of our lands and culture? What traditions if my generation and those to come are left with the traces of what used to be?" Where is this greed taking us?”

A bag of Oaxacan sand sat in a plastic freezer bag on a sculptural pedestal, evoking the high value placed on fine art through a material all but overlooked by society, save the sand mafias. So valuable is sand in places like Oaxaca that, per the BBC, sand mafias have been linked to hundreds of murders around the world over the last few years. This led the artist to adopt the moniker Sin Sombras to protect her family amid the criticism she levies against the extractive practices that transform rivers into destroyed ecosystems and sand into concrete.

Sin Sombras haltingly recounted the hostile actions mining companies had taken against locals who oppose them. A neighbor who spoke out against the practices at a public assembly in her town was later pulled from his home, stripped of his clothes, and beaten, his body left beside the river he was trying to save. Her community organized a blockade of trucks extracting the sand, but few consequences followed, leading to a fatalistic pessimism in which resistance seemed futile; many, like her cousin and uncle, now participate in the extraction.

Down the hall from Sin Sombra's work, Niemeyer's photographs highlighted China's uber-ambitious Belt and Road Initiative through Kenya Vision 2030, in which the Kenyan Government contracted a Chinese construction company to build the dam to power the "Silicon Savannah.” Through Niemeyer's lens, we see Chinese officials planning a massive dam. Under the agreed terms, if the Kenyan government defaults on payments, China would take over the dam and control its electricity. Adjacent photos show the early effects on Kenyans who are already adjusting to the precursors of such a developing reality, in which centuries of shared use of water holes have been reduced to private property and paying to use water now controlled by corporate entities.

Around the corner, artist Asma Kazmi created Begging Bowls, a poignant installation in which dozens of ceramic pinch pots sat on the concrete floor as if upturned mushroom caps. The artist made the pinch pots to resemble kashkuls, or begging bowls, historically used in the artist's native Pakistan by mendicant Sufi monks known as dervishes, who use the bowls to accept sustenance offerings in exchange for spiritual guidance. The empty bowls wait in line to be filled with water from a leaking street-side faucet that runs on a video loop. Kazmi made the video with AI. AI data centers can require significant water withdrawals, leading to fears that AI's incredible water consumption will have a major environmental impact. As the AI video can't pass from its digital world into ours to actually fill the bowls with sustenance, it leaves one to wonder about the exchange of this new technology for an essential resource. The empty bowls hint at what society may well be getting in return for generative AI's magic act of transforming water into information.

A nearby room filled with informative posters on the San Francisco seawall’s potential impact took on the feel of a trade show, educating stakeholders on what's to come. Yet, amid the exhibition and a piece on loan from James Lowry's mining museum, above the posters hung two pipes from a rope. Niemeyer told me the wood and bent lead pipe hanging from the rope represent America's centuries-old practice of using toxic lead pipes and wood to deliver water to homes. Niemeyer noted that both lead and wood pipes are still used as service lines to deliver water to parts of America today.

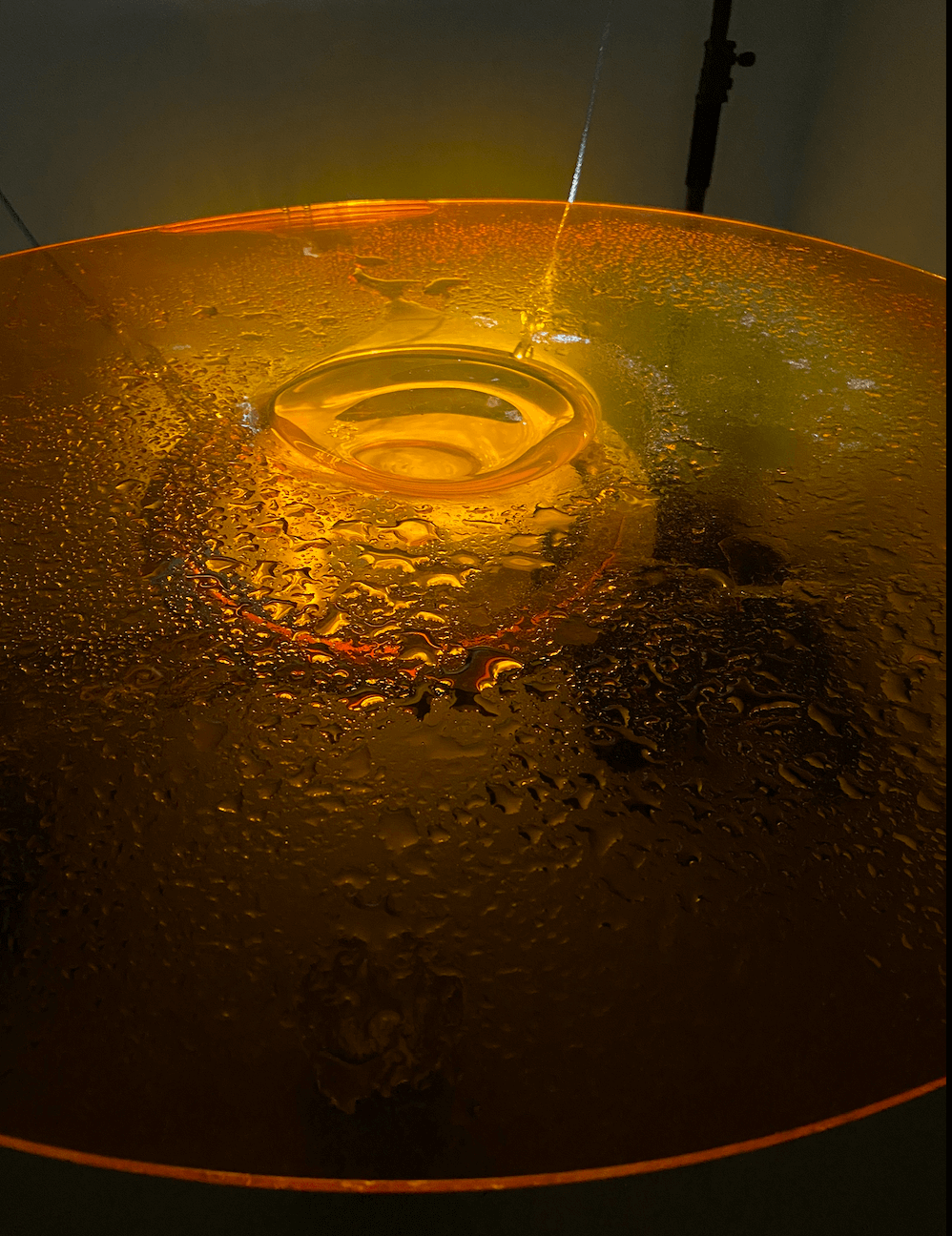

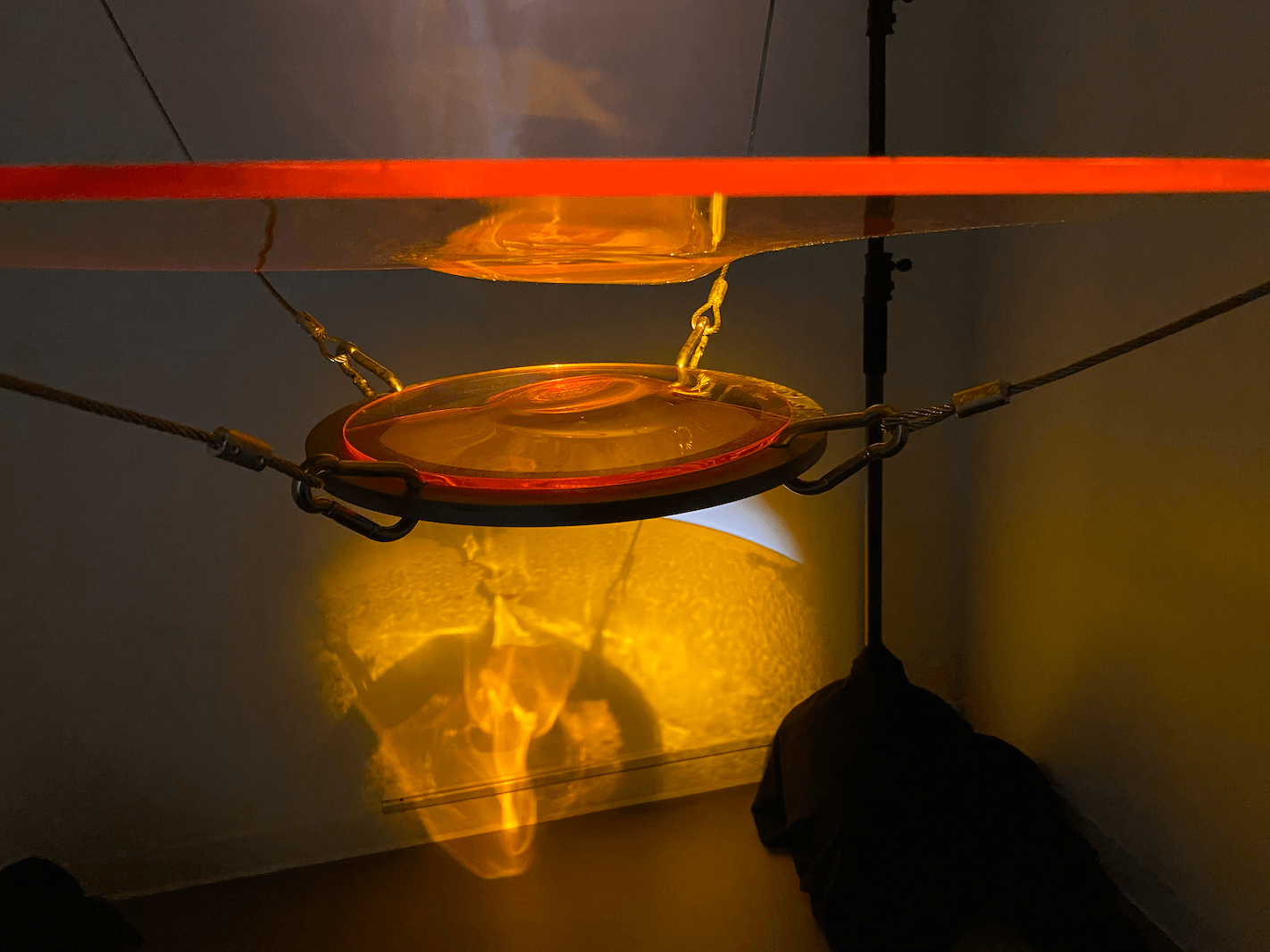

Amid the dark shadows brought to light in the exhibition, optimism emerged through installations that framed water as a prism, allowing us to see our impact on it and its impact on us. In Koh Terai's meditative water/light/glass installation, Go With the Flow, water dripped from above onto a glass plate illuminated by the room’s sole light source. Each time a drop splashed onto the plate, the illusion on the wall changed. The work invites us to see water as a lens through which light passes, affecting color and perception, and to consider water not as something to control but as a medium with which we interact. A sound installation by Niemeyer and his wife Lisa gave water's calming sounds a place in a dark room, where overstimulated gallery-goers can catch their breath and reconnect with what has been done for thousands of years, listening to water's movement as a sound of personal and ecological rejuvenation.

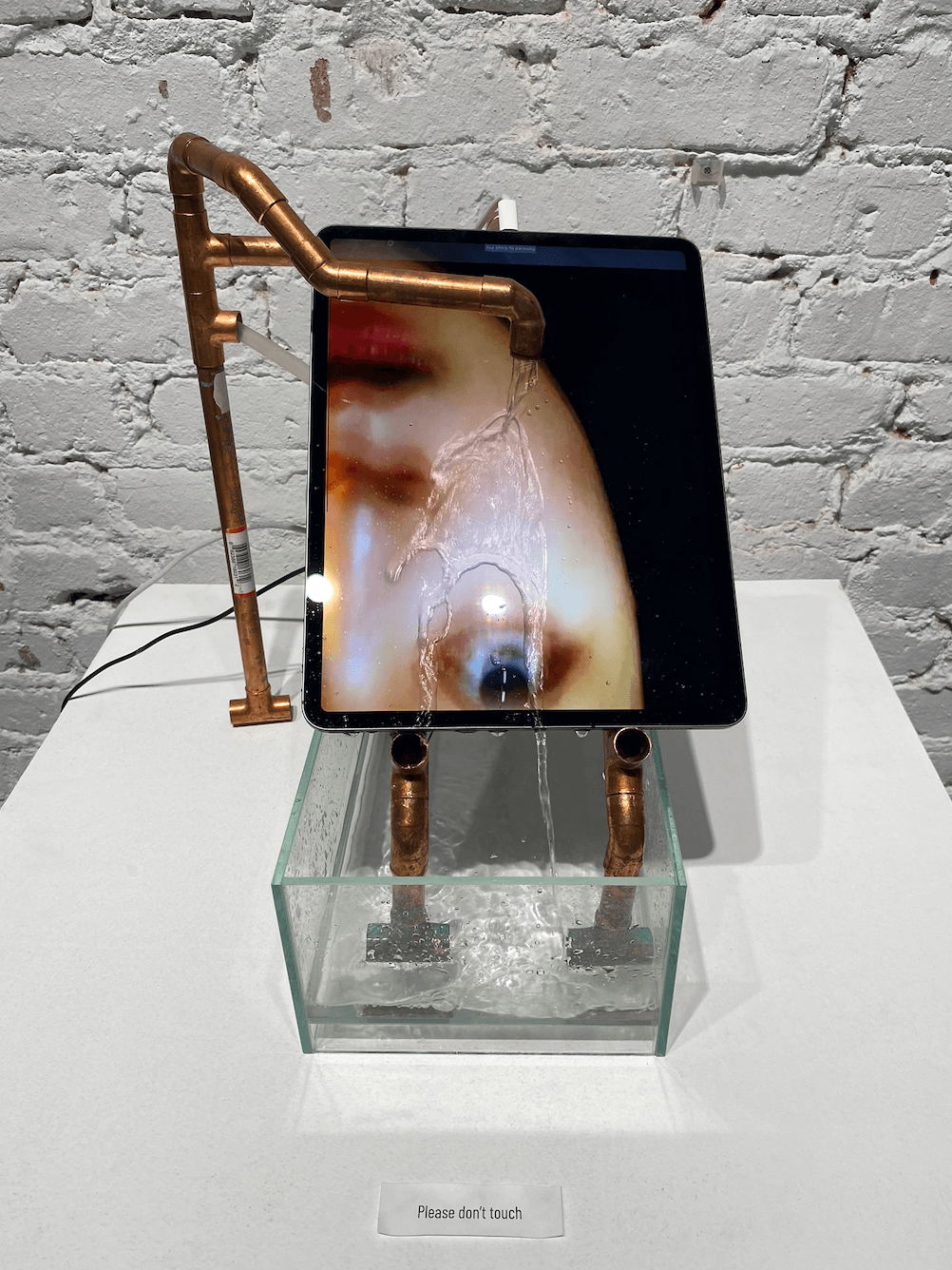

Yehwan Song's Fountain highlighted the materialization of digital media's human impact. By inverting screen scrolling's attention-grabbing power, the viewer becomes a witness to interpassivity, or the phenomenon of a person outsourcing their joy and beliefs to an external agent like a smartphone. Here, the intimacy of a human face with closed eyes is trapped in the machine. Then the eyes open, the face comes to life with expressions of emotion as water, a metaphor for the flow of information, floods across the iPad's surface. Instead of the subject scrolling, they are being scrolled, the viewer's perspective has become that of a device, allowing us to see society's screen addiction and interpassivity.

Of the programming, Niemeyer told me that after Luiz Barata spoke to the audience of some 60 people on San Francisco's $13.5 billion plan to build a protective sea wall, the curator polled the audience on whether the money would be better used to fund relocation rather than hardening the shoreline, 90% remained undecided. "This is the point of exhibitions like this and using spaces for collaborative meaning making and art, sea levels are rising, it's inevitable, and none of us knows what to do about it." Niemeyer went on to tell me in a phone conversation that society is threatened by "A failure of imagination. If we keep refusing to imagine massive change, these things in our environment will inevitably change, and we will suffer for it. Art helps us imagine these new potentials and reimagine water as a medium to develop solidarities with and not simply view it as an object."

Although the exhibition closed in San Francisco on January 25, 2026, and was preceded by one in Detroit at the Gordon L. Grosscup Museum of Anthropology at Wayne State University, Niemeyer expressed optimism that it could continue at a future location in another city. Water Futures shows us that an equitable and sustainable future with water won't be solved with infrastructure alone; we also need spaces that foster non-transactional dialogue and collaborative imagination. If the exhibition model holds true, it isn’t just relevant to the future of water but also a needed direction for the future of the art world.