Love Letters to Aliens, Southern Exposure (SoEx)

Upon entering Southern Exposure’s exhibition Love Letters to Aliens, visitors are greeted by a graphic visualization of the show's title. An organic cluster of neon-green concentric circles, like digital tree rings, floats within a slick black rectangle, subsumed by a wall of ornate text. The text takes the form of a letter from the show’s curator, artist Sholeh Asgary, addressed to the group of artists featured in the exhibition: Rana Hamadeh, Xandra Ibarra, Osvaldo Ramirez Castillo, Maryam Tafakory, and Yue Xiang. Asgary’s words precipitate an exploration of “how intimately and vastly we occupy time and space when edges meet,” prompting both the show's artists and audience to consider “what is a border but the beginning or ending of things?”

Around the corner, an installation called The Surface of Things, 2025, by Xandra Ibarra follows. Here, two floor sculptures, a wall-hung object, and a site-specific burn are in conversation, all elements composed from various material combinations of metal(s), leather, and the South American “holy wood,” Palo Santo. Measuring about 4 ft in diameter each, the floor sculptures mimic stainless steel surgical tables gone wrong, toppled over, with legs bent and contorted in ways that seem to provide a precarious kind of support. Rust-colored leather skins embossed with gridded brick patterns are draped over rectangular metal tabletop slabs, positioned like low horizontal easels. Close to the floor, this vertical display requires viewers to peer downward to take in more details, such as adorning polished silver chains, charred sticks of Palo Santo, and raw metal sheets bearing pictorial impressions that summon images of intestines, scars, rivers, lines drawn in sand, or other bodily pathways.

High up on the wall behind them, a smaller embossed metal rectangle hangs, its corners forcefully secured to the white-painted surface with visible metal screws. A half-moon-shaped skin is adhered to its front, held in place by a dangling round rock adjoined to the head of a sharp metal rod. A poignant tension between dominance and submission is captured here; the slightly cocked needle reads as a dormant riding crop, while the shape of the leather piece emulates the curved underside of a horse's belly.

Directly below the needle's tip, a series of smoky marks creates the impression of a horizontal line spanning the width of the entire wall. One can imagine the pattern is formed by the tip of a smoldering Palo Santo stick ritualistically tapped against the wall in methodical succession, carefully held in place just long enough to capture a round blister and subsequent stream of vapor, but not enough to penetrate the painted surface. While there is no literal figurative element present here, or in the rest of Ibarra’s installation, actions done to and by a body are felt viscerally throughout, as material thresholds interface and “surface becomes a gateway,” invoking paradoxical sensations of protection and vulnerability, flow and anxiety.

Across the gallery stands Yue Xiang’s Witness, 2025. Here, a large black-shrouded, furniture-like figure, perhaps a reliquary cabinet of sorts, sits in the center of a synthetic green-grass soccer turf carpet. White lines are spray-painted down the middle and two rectangular goal boxes on either side. At nearly 10 ft tall, the central figure feels existentially huge and heavy within the empty, imaginary sports field, sprawling a modest 6 × 16 ft on the floor. The figure reads as anthropomorphic, reminiscent of some sort of seated deity on a throne. Or is it just a tall, thin cupboard painted black, with its top cabinet door gestured wide open?

Sheer black chiffon fabric encompasses the figural object. From far away, it appears dense and monolithic, but upon closer inspection (viewers are encouraged to walk onto the playing field), one notices small, mysterious elements sewn into its folds. Bright red string secures hundreds of stark white buttons, while broken bits of blue-and-white pottery and dried flowers are enclosed in mesh pockets. As the viewer leans in, one hears the sounds of rhythmic heavy breathing, while a small portable radio placed at the foot of the figure plays a historic recording: the 2024 game in which the Palestinian National Football Team won their first match during the Asian Cup in Qatar, beating Hong Kong 3–0.

On this particular work, Xiang has written:

“If Palestinians are considered Asian, would our conversations around the genocide in Gaza shift? … Who are we cheering for? Who are we rooting against? What do we feel as witnesses to this geopolitical game? Are we active participants, or passive bystanders? What changes when we choose to step into the game? What emotions surface in that choice?”

This installation invites its audience to consider and reflect on their own positions, and positionalities, within the game. The shrouded figural furniture-object invites close inspection and introspection, while viewers are encouraged to consider the implications of their own perceived measurements.

On two other adjacent gallery walls, one encounters work by Osvaldo Ramirez Castillo. Just behind Xiang’s Witness, three delicate mixed-media drawings are mounted to the white-painted surface with magnets, unframed. Each, ranging in scale from a little over or under a foot, is composed of painted and cut paper, layered and collaged to create the effect of a figural narrative floating in the space of the page. Untitled, 2025, measures 16 in. tall and shows an achromatic rendering of a man’s torso positioned as if his hands are in his pockets, but instead of pants we see blue-green leaves and other foliage stacked upon a tripod structure made of entwined sticks. The sticks mingle with some sort of root system below, encasing a floating green mass, from which pink flowers bloom up behind the figure. At the top, a bright yellow sun radiates behind the figure's head, which appears bovine, adorned with more flowers. Symbols feel at once personal and collective here, as if the image is collapsing a multitude of histories, cosmologies, and stories into one, then regenerating. The stacked cut-paper elements create shadows on the surrounding white sheet, making the image feel heavy with the literal and metaphorical weight of symbolic objects, despite hovering.

On the adjacent wall, Osvaldo presents a site-specific mural called Nahual, 2025, measuring about 20 ft wide by 7.5 ft tall. Rendered in black acrylic, two figures are painted in a style that calls to mind woodcut printing. The left figure is shown lying horizontally, arms to the side, legs straight out, wearing pants but no shoes, and appears stiff and listless, like a cadaver. From its stomach and face sprout large black spikes of foliage and protruding pointy vegetation, as if the body is a shell or husk for other new life to grow from. The figure to the right is shown many feet away, crouching toward the supine body. Subsumed in what appears to be a garment made of grass, only the crouched figure's shoulder, shin, and bare foot are exposed. Its head is consumed by flower petals, like a mum or chrysanthemum. In the center, an unfinished part of the mural is exposed: what appears to be a circular eye lightly drawn in pencil, calling to mind visions of tiny blossoms being plucked bare from a flower’s central capitulum.

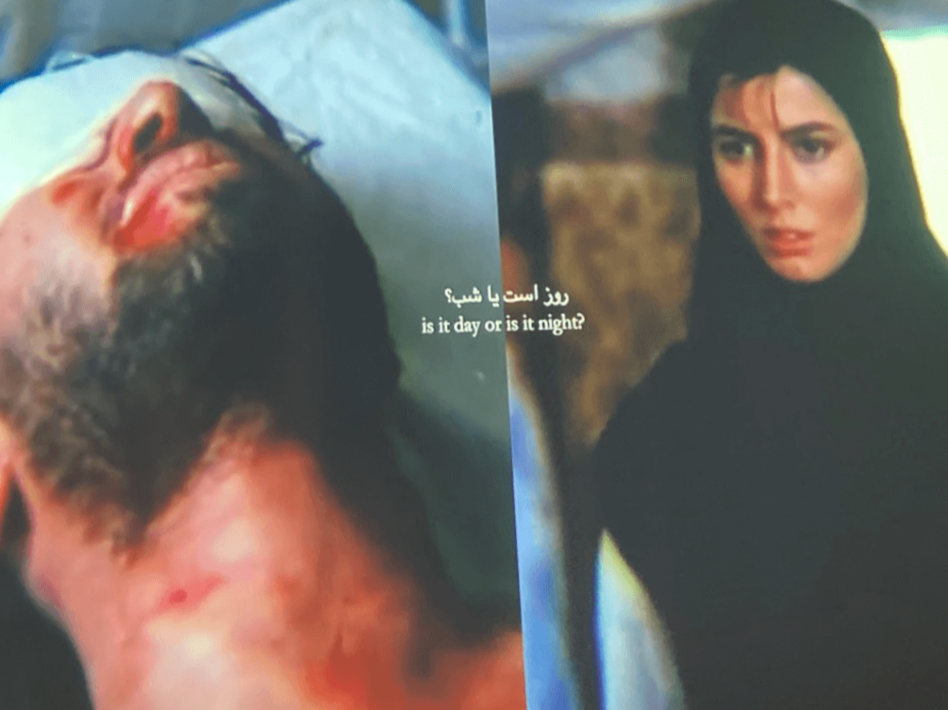

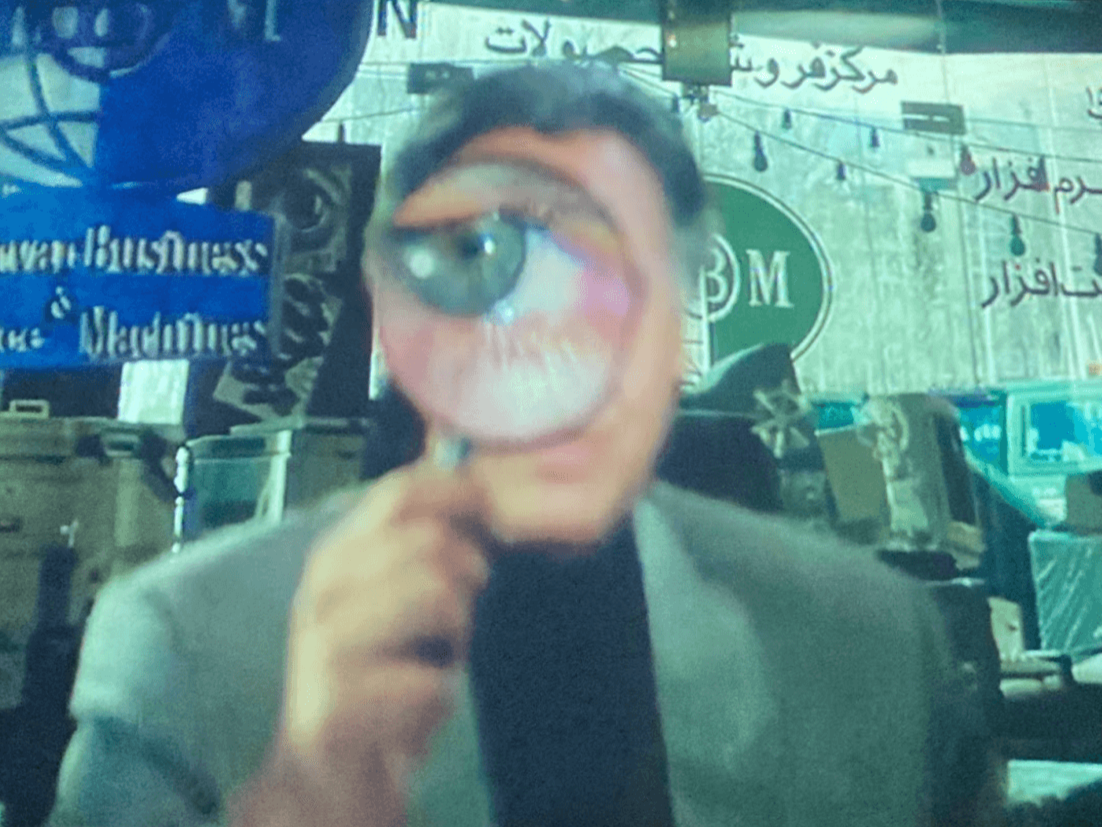

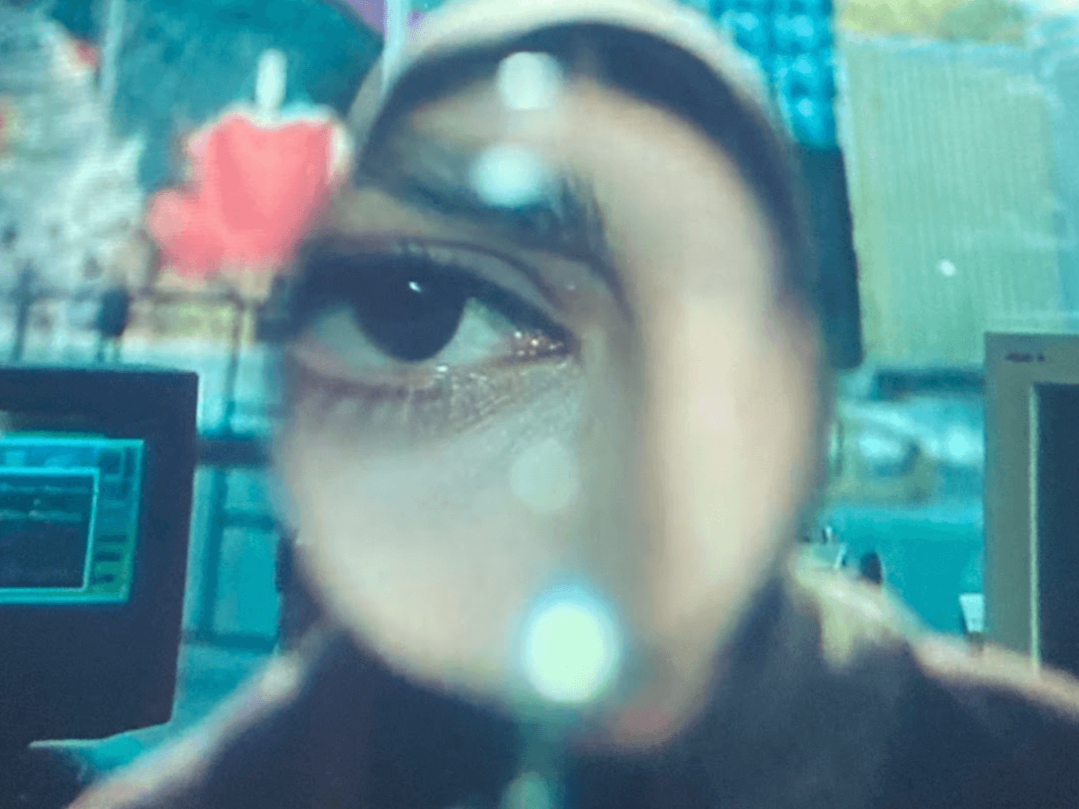

Behind a black curtain between the walls featuring Osvaldo’s work, visitors find a small dark room to view Maryam Tafakory’s film Nazarbazi / نظربازی (The Play of Glances), from 2021. A collage in moving images, the film is a carefully edited montage of scenes pulled from post-revolutionary Iranian cinema (emerging after 1979), where depictions of intimacy and touch between women and men are prohibited. Themes of erasure and desire are expressed through the transference of objects, glances, and discrete forms of communication that, according to the artist, “operate within yet circumnavigate the censors.” Between visually stunning clips pulse dark silent screens with small text, poetry and silence, which the artist refers to as “the only languages with which we can touch these spaces of socio-political ambiguities.”

There are numerous moments where the film's audience is permitted to observe such intimate transitions and transactions, where a stand-in for physical “touch” is energetically sent through a thing itself, as opposed to body-to-body. One poignant example: a bearded young man lies injured in a hospital bed, with a bandage over his eyes. He’s still, perhaps unconscious or immobilized with pain, as a woman wearing a deep blue hijab stands a few feet away from him. She might be his caretaker or a nurse, but she looks at him intensely like a lover, and gently pushes a cotton swab into an open wound on his arm. The wound is deep red and bloody, as is the swab, and the sanitizing, dabbing motion is rhythmic, as shots of the woman's eyes are consumed by the camera. The man remains blindfolded by his bandages, but there is a sense that he is receiving some sort of transference through this pattern.

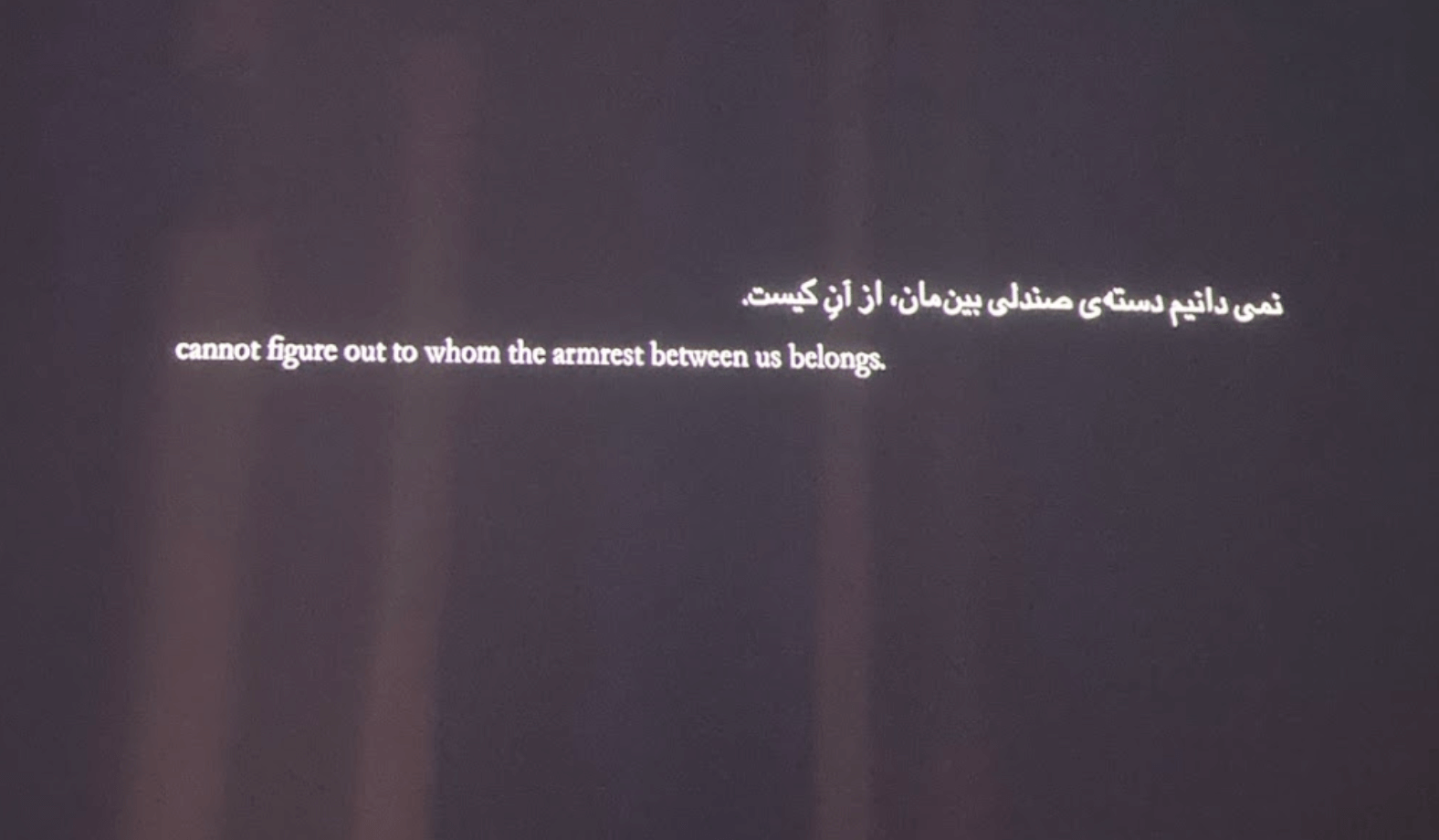

Later on, a poem interjects between collage-cut images, reading frame by frame in interrupted succession:

“in revolution square… in the blind spot of the auditorium… me and the stranger next to me… cannot figure out to whom the armrest between us belongs…”

The armrest becomes an object of transference, a space of negotiation, a border or boundary: a space where multiplicities exist, and where what is understood before or after they begin or end may feel more or less familiar depending on one’s own positionality.

Wandering the exhibition, notions of the abject as described by Julia Kristeva come to mind. A primal response to a material or psychic trigger, the abject emerges when boundaries between self and other, subject and object, inside and outside, begin to collapse. It occupies what Kristeva names “the in-between, the ambiguous, the composite,” a space of destabilization that is neither wholly repulsive nor fully assimilable. Across Love Letters to Aliens, bodies are rarely shown outright, yet their pressures, wounds, desires, and negotiations are everywhere inscribed: in scorched walls, suspended glances, vegetal eruptions, stitched reliquaries, and objects that stand in for touch, care, or harm. What binds the exhibition is not a singular narrative but a shared insistence on thresholds as sites of both risk and possibility, where meaning is generated precisely through friction. In this way, Love Letters to Aliens does not ask viewers to resolve the discomfort of these encounters, but to remain with them, to recognize borders not as fixed lines to fortify or transgress, but as living spaces where new forms of relation, witnessing, and becoming tentatively begin.

Show Info:

Love Letters to Aliens, curated by Sholeh Asgary, featuring artists Rana Hamadeh, Xandra Ibarra, Osvaldo Ramirez Castillo, Maryam Tafakory, and Yue Xiang

Southern Exposure (SoEx), 3030 20th Street, San Francisco

Sow runs October 25, 2025 – February 7, 2026

*Closing Reception & Closing Performance by Roco Córdova: Saturday, February 7, 2026, 5:00 PM - 8:00 PM, Free

1. Love Letters to Aliens, Exhibition Pamphlet, Southern Exposure, 2025

2. Love Letters to Aliens, Exhibition Pamphlet, Southern Exposure, 2025

3. https://www.espn.com/soccer/match/_/gameId/668948/palestine-hong-kong

4. Love Letters to Aliens, Exhibition Pamphlet, Southern Exposure, 2025

5. https://read.dukeupress.edu/books/book/542/Displaced-AllegoriesPost-Revolutionary-Iranian

6. Love Letters to Aliens, Artist Press Materials, Southern Exposure, 2025

7. Julia Kristeva, Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection, ed. Leon S. Roudiez (New York: Columbia University Press, 1982), 4