Tiffany Shlain and Ken Goldberg

Tiffany Shlain: Honored by Newsweek as one of the "Women Shaping the 21st Century," Tiffany Shlain is a multidisciplinary artist, Emmy-nominated filmmaker, national bestselling author, and the founder of the Webby Awards. Working across mediums, Shlain's work explores ideas in feminism, philosophy, technology, neuroscience, and nature. Her work has been shown at the Museum of Modern Art and the Guggenheim Museum in New York, the Sundance Film Festival, and US embassies globally.

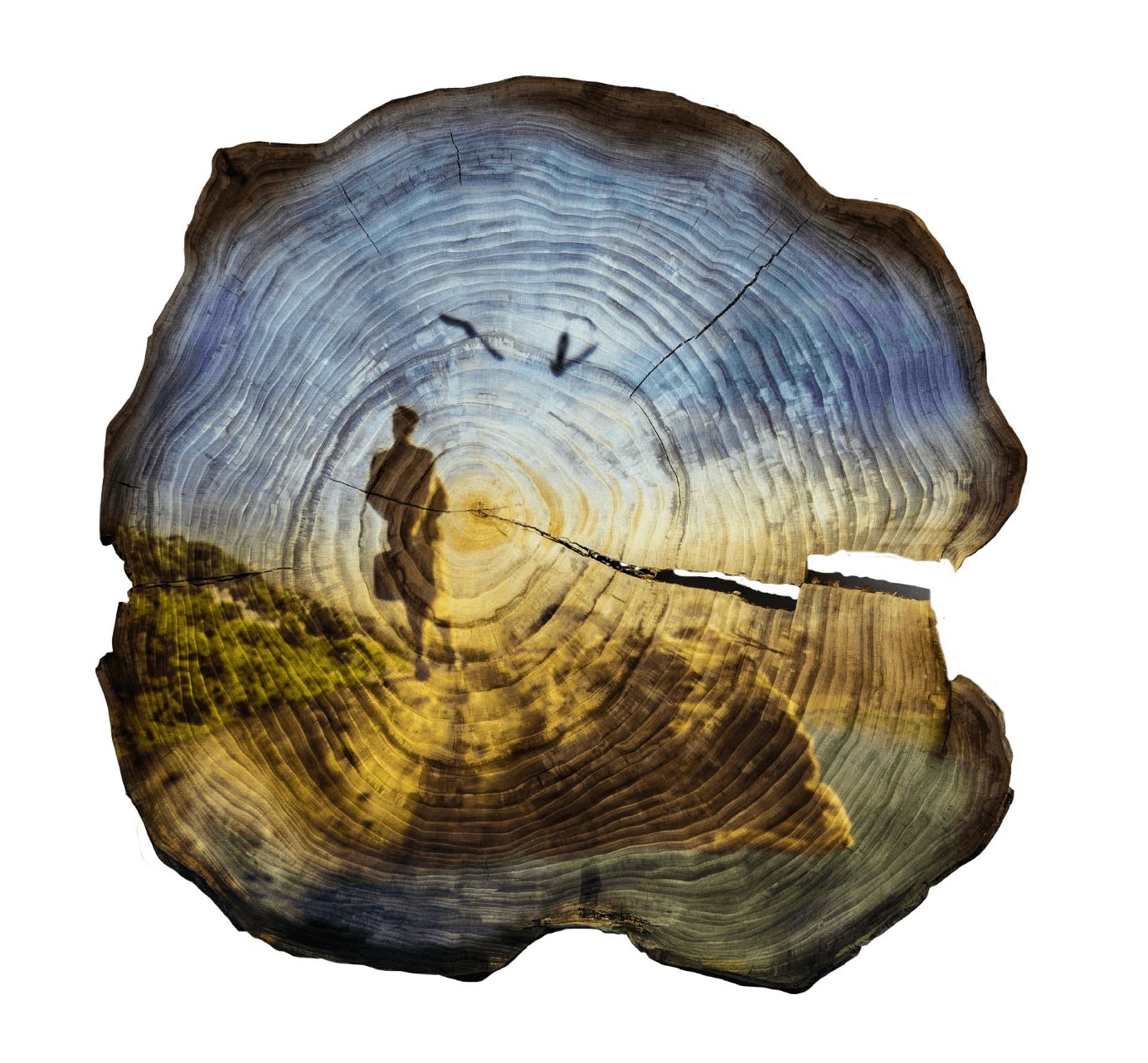

Her sculpture Dendrofemonology A Feminist History Tree Ring was installed on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. and was in Madison Square Park in NYC for a Mobilization for Women's Rights and the Planet to kick off Climate Week Sept 2024. Highlights can be seen in her new short film We Are Here. Nancy Hoffman Gallery presented her acclaimed solo exhibition You Are Here. Dendrofemonology is currently on view at 21c Museum's exhibition The Future is Female, along with 50 feminist artists, including Jenny Holzer, Carrie Mae Weems, Zoë Buckman, Mickalene Thomas, and Andrea Bowers, until June 2026.

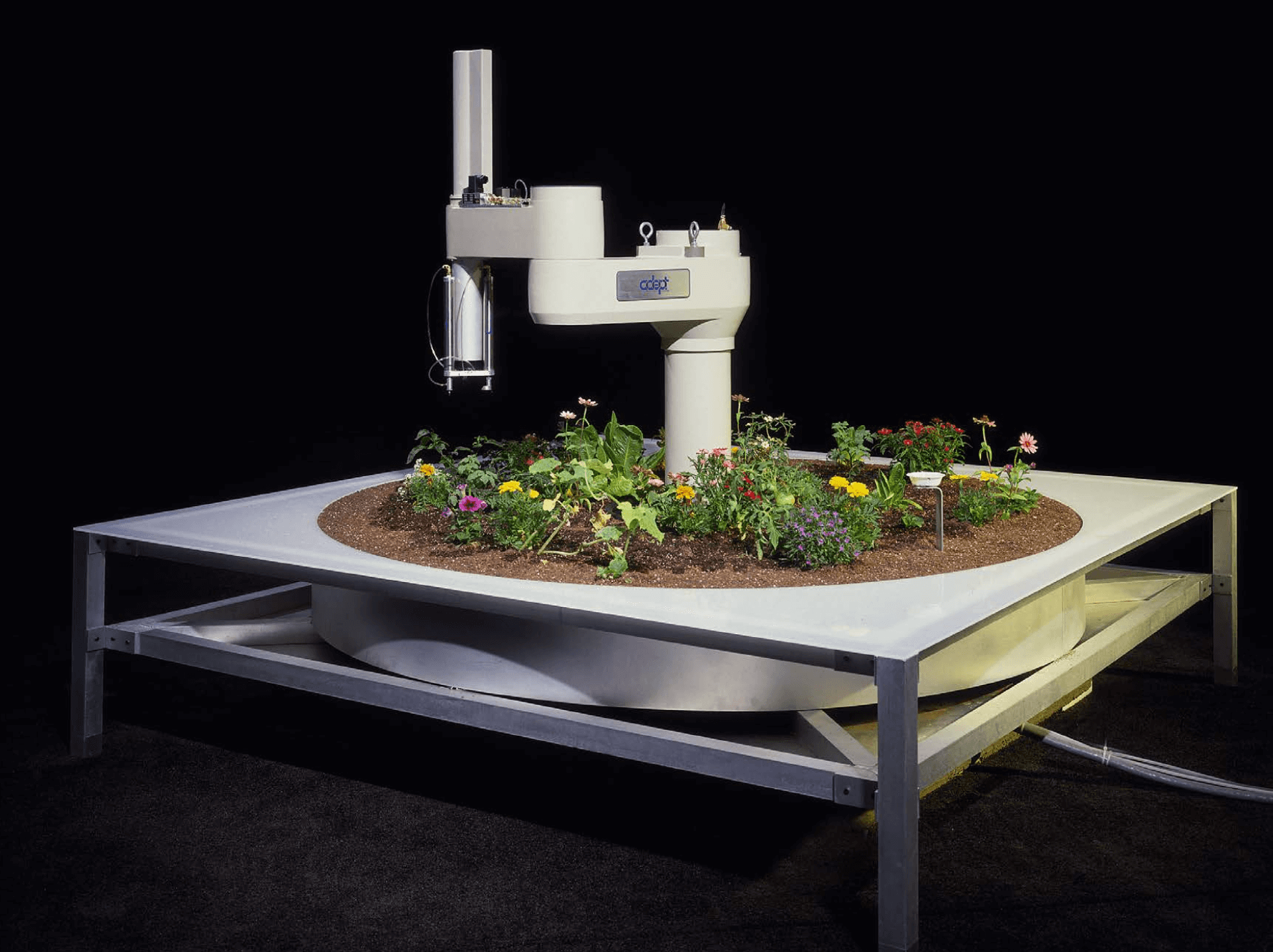

Ken Goldberg uses new technologies to express the contrasts betweenwhat is natural and what is artificial – the liminal spaces betweenreality and representation. His artworks include a live garden tendedby a robot controlled by over 100,000 people via the internet, a 1millionth scale model of Frank Lloyd Wright's Fallingwater in silicon,installations generated by live seismic data, and award-winning balletand short documentary films. Goldberg's art has been exhibited at theWhitney Biennial, Venice Biennale, Pompidou Center, Walker Art Center,Ars Electronica (Linz Austria), ZKM (Karlsruhe), ICC Biennale (Tokyo), Kwangju Biennale (Seoul), Artists Space, and The Kitchen. His work isin the permanent collections of the Berkeley Art Museum, the NevadaMuseum of Art, and the Whitney Museum of American Art. Goldberg isProfessor of Engineering and Art Practice at UC Berkeley and FoundingDirector of Berkeley's Art, Technology, and Culture Colloquium. He isrepresented by the Catharine Clark Gallery in San Francisco.

The following are excerpts from Tiffany Shlain and Ken Goldberg’s interview.

Hugh Leeman: You two have an incredible story—your meeting, marriage, children, and a decades-long creative, collaborative practice. Can you share that story? What stayed surprisingly consistent over the years that’s allowed you to collaborate?

Ken Goldberg: Great question.

Tiffany Shlain: We met on Jan 24th, 1997.

KG: 1997.

We had a number of friends in common. I had moved up to Berkeley, teaching in the engineering college, and I’d read a book called Art in Physics. Three friends gave it to me and said, “You have to read this,” because it was right in the center of my interests—art and technology. Then I was invited to hear a lecture by Dr. Leonard Shlain, the author. It was a dark, rainy January night, and I drove over to—

TS: It was the gallery in Jackson Square—Canessa Gallery.

KG: Right. I came into the gallery and saw Dr. Shlain loading books for the lecture. I said, “Can I help you?” We started talking and I said, “I’m a professor at Berkeley, I’m interested in art and science, and I’m a big fan of your book.”

TS: The way I remember it: first of all, my late father was an amazing speaker. My friends and I would always go hear his talks because it was such a dynamic experience. So I was there with ten of my best friends, hearing my dad speak at this art gallery on Art & Physics And the way my father would tell it is: this handsome man walks up and says, “I’m a big fan of your work. I’m a new professor at UC Berkeley. My name is Ken Goldberg.” And my dad says, “Have you met my daughter Tiffany?” He introduced us, and we fell in love right there.

Another friend of ours, David Pescovitz, was also there. He played a part in the introductions because he was one of our mutual friends.

So basically, that night was pretty much our first date—and it was with my dad and ten of my best friends. And we all went to Bix.

HL: Wow. That’s incredibly romantic. To give a bit of context for your collaborations: you did The Future Starts Here—Emmy-nominated. Before that you co-wrote the hit film The Tribe—it premiered at Sundance. You’ve won dozens of awards. Beyond the romantic meeting story, how do you navigate the emotions of creative collaboration so that the spectrum of emotion and interaction stays collaborative, instead of competitive?

TS: We didn’t collaborate for the first—how many years?

KG: The first six years or so. And you’re right, Hugh—we both have pretty strong personalities, and we were nervous.

TS: About venturing there.

KG: Yeah. We thought we might kill each other if we tried.

TS: But the breakthrough was having our first child. Seven years in, we had our daughter Odessa—and I think that’s the ultimate collaboration.

KG: Yeah. But let me back up a little. Right after we met, Tiffany was in the early stages of forming the Webby Awards—her interest in technology and film and design and art. We spent a lot of time talking about how she was doing that, and how to make it different from the typical technology show or awards show.

Meanwhile, I was at Berkeley and I had started a lecture series called Art, Technology, and Culture—meant to bring together artists, writers, and curators who shared this interest in art, technology, and culture. So we both had these new programs we were initiating, bringing people together from different backgrounds in different ways. We spent a lot of time advising each other on our projects. But there was a distinction: her realm was films and the Webby Awards, and my realm was art installations and my lab work. Over time, we started thinking about how we might combine forces.

TS: Our first project was The Tribe. I was really eager to make it—partly inspired by the creator of the Barbie doll. It was such a fun subject for us to co-write. We love talking to each other, so co-writing was a great entry point. In a lot of ways, that film distilled years of conversation into an eighteen-minute script. We both love making each other laugh. We have the same sense of humor, and we love going deep on subjects. That script was a distillation of years of conversation—and—

KG: It was conversation about something very specific. We were talking about lots of things, but in that case it was about being Jewish in America.

TS: Yeah. And that film had a really great run. We just had the twenty-year anniversary screening from when it premiered at Sundance, and it was fun to look back. When you revisit a film years later, you wonder, “Would I change a line?” But we spent four months on one line. We’re really into crafting and editing. Ken loves bringing out a red pen. We have a lot of discussions: what do we agree with in an edit, what don’t we agree with?

One of our daughters said she loves seeing us go back and forth with edits because we do a lot of them by hand—you can really see our conversation in the edits.

And then the next thing we did was an art installation. It’s interesting: we co-wrote The Tribe, but I was the director. Then we did an installation—more Ken’s arena at the time—called Smashing. It had a film component, but in terms of the installation, I looked to him as the expert there.

And then with this show—we got approached for the show that’s opening in San Francisco, Ancient Wisdom, it became a truly joint museum exhibition. We’re still leaning on each other’s expertise—whether it’s sculpture for me or AI for Ken—but we collaborated on the whole exhibition together.

HL: Incredible. Let’s pull a few threads together. You mentioned being Jewish in America, the Barbie project, AI, and technology as part of your creative ecology—and also your daughters. How have your children influenced your perspectives on time, especially as it connects to the “technology Shabbat” you’ve instituted, which you’ve described as life-changing? How has that changed your attention—your relationships with your daughters, your relationship with time, and with yourselves?

TS: I grew up Jewish, but not practicing Shabbat. Ken did, and—

KG: I grew up in Pennsylvania. We weren’t particularly religious, but we did celebrate Shabbat dinners on Friday nights. I had a little more of a Jewish-focused upbringing than Tiffany did.

TS: Ours was more Jewish culture.

KG: Yeah. Neither of us were religious. But when we had our first daughter, Odessa, it brought us together in a new way. We had a lot of mutual decisions to make—everything from sleep patterns to where we would live.

TS: And also, something big happened in that period: the iPhone came out when Odessa was maybe three or four. We loved technology—our whole lives—but it started taking over every space, and it didn’t feel good.

Around when Odessa was five, my father—who I was very close to, and so was Ken—was diagnosed with brain cancer and given nine months to live, just as we found out we were pregnant with our second child. It was an intense period. My father died, and days later our second daughter was born. It was a wake-up call moment. I felt like the iPhone and computers were distracting every moment.

So we decided to implement our version of Shabbat, which was screen-free.

KG: The precedent for that was: when I was in grad school, I lived in Israel for a while. On Saturdays there, you can’t really do anything—buses shut down, everything closes. I ended up painting, reading, hanging out, relaxing. I grew to really like it. When I came back, I kept taking Saturdays off—no work, just relaxing and fun without guilt. I continued that for years. I worked hard at Berkeley, but not on Saturdays.

TS: And then the iPhone changed everything. I loved that boundary you had, but the iPhone blurred every boundary between work and rest. We participated in the National Day of Unplugging—one ceremonial day—and it was such a relief. I felt present again with our children and each other, and out in nature. We just never stopped.

And the more we did it, the more benefits appeared. Especially as artists—it’s the day my best ideas come. I do a lot of journaling. Friday nights are social because we have people over for Shabbat dinner, but Saturdays are trees and nature and reflection. Our society doesn’t make space for that anymore with so many distractions.

KG: It’s nice to have one day where you aren’t making plans—you keep it open. We spent a lot of time just puttering around with the girls, making things, playing games.

TS: That was when they were younger. Now our older daughter Odessa lives in Brooklyn—she’s almost twenty-three—and our younger one, Blooma, is a junior in high school. By when they were young, It created an incredible “nest” of a twenty-four-hour period, and it’s evolved as the kids have gotten older.

KG: When they were younger, it was the day we looked forward to—where we didn’t feel the pressure of rushing around. It’s grown into something like a vacation every week. People are afraid of the idea—“I can’t stop looking at my phone for a day”—but it’s surprisingly easy once it’s a habit, once your friends understand. Having a day to yourself has been really helpful.

HL: It’s incredible. I think of Jonathan Haidt’s book about the anxious generation—phones out of schools—and it feels like you’re living proof of the power of that. Your work combines tree dating, artificial intelligence, and Jewish thought, among other things. What is Jewish thought—and how does it intersect with AI and tree dating?

TS: At the heart of Jewish philosophy is questioning absolutely everything. I didn’t realize until I was older how unique that is. And we’re not religious. Most people don’t understand Judaism can be cultural—you can be atheist or agnostic and be Jewish. It’s a way of approaching the world: question everything.

With AI, that’s especially relevant. You need to know how to ask interesting questions in prompts. And with deepfakes and disinformation, you have to question everything you’re seeing online. So AI and Jewish thought meet at that core: questioning.

My tree-ring sculptures were also about questioning—questioning traditional historical timelines on tree rings and challenging conventional wisdom around them. That feels deeply connected to how I was raised: always questioning.

KG: We’re always looking at intersections—technology and nature, and also alternative views of history. We go back and try to understand how things happened over time and how they’ve been perceived. Especially lately, there’s been so much misinformation and trauma, and we’re working through that.

AI interests us because it’s an abstraction—almost a dematerialization of ideas. New ways of thinking. There’s something deeply Jewish about that, too.

TS: And the show—Ancient Wisdom for a Future Ecology: Trees, Time & Technology—is an expanded version of what was part of Getty’s PST Art in LA. We’re tackling other subjects too: the history of science, the history of California. Ken has this great tree census work.

We’re also using AI to help visitors create tree tributes—to acknowledge a tree. There might be a tree outside your house you’ve always admired, but you don’t know how old it is or its name. There’s a project in the show that helps you do that, and Ken can explain more.

HL: Thank you for sharing that. I really like this idea that you can be agnostic and—

KS: Most people don’t know that.

HL: Yeah, I didn’t know that. That’s impressive.

TS: A lot of Jews I know are atheists, too.

HL: Tiffany, you once noted that writing The Tribe was “a distillation of all of our conversations about being Jewish and an assimilated culture.” That idea feels as fraught now as ever. And it’s interesting because you’re also the raw material—it’s your shared life. How did you decide what becomes comedy, what becomes critique, and what gets the red pen and stays private?

TS: You’re asking great questions. In all my films, I try to make people laugh before I say something I want them to be open to thinking about. Humor opens people up. When you laugh, your body language changes—you become more open to an idea in a new way. I love making people laugh in a theater, and I love making people laugh with art.

Movies are meant to move people. Art can do that too. But we’re also dealing with intense stuff, especially the last couple years. I’m fifty-five, and it’s been the hardest couple years of my life being Jewish. There’s a lot of misunderstanding about a lot of things.

KG: I grew up in a family with a lot of laughter too. There’s Jewish humor, but also humor as a way to disarm people, or help them relax. I use it in my classes, in lectures.

TS: We give a lot of talks, and we love that.

KG: People don’t want to sit through a lecture that just goes on with facts. Visual storytelling helps. In my talks and teaching I use a lot of images and videos.

TS: And that’s where Ken is unique. When I first met him, being an artist and a roboticist was such a rare combination. That combination—art and science, art and technology—was one of our main connection points. We’re always trying to translate and make ideas accessible to the public in both spaces.

HL: This idea of art and technology comes together in a big way through your exhibition, Ancient Wisdom for a Future Ecology: Trees, Time, and Technology at the art center. It has deep roots and far-reaching limbs—many components. Take us through the exhibition’s different parts.

KG: You’re going to walk into a beautiful space in Dog Patch, in the Minnesota Street Project arts campus. It’s the di Ros Center for Contemporary Art in SF. They have a great museum and outdoor sculpture spacein Napa and then recently opened a satellite museum space up in San Francisco.

KG: So we’re installing it there. You walk through glass doors. There’s a collection is devoted to Northern California artists—the curatory Twyla Ruby also curated a show from the di Rosa Collection to be in conversation with our exhibition, all artworks exploring time called Counter Clockwise. It’s a 7000 square foot space, so there several different galleries in the museum. The first one the curator selected works from each of our individual careers before you then go into a large space with wooden sculptures are installed.., and in the media room there is an artwork that is a tribute to Ed Ruscha that we developed in Los Angeles.

It’s a video timeline—a tracking video of major San Francisco streets from above. If you know Ruscha’s films of Hollywood Boulevard and Sunset Boulevard, this takes that idea, rotates the point of view ninety degrees, and emphasizes treescapes along streets—and how they vary depending on affluence, because there’s real variation.

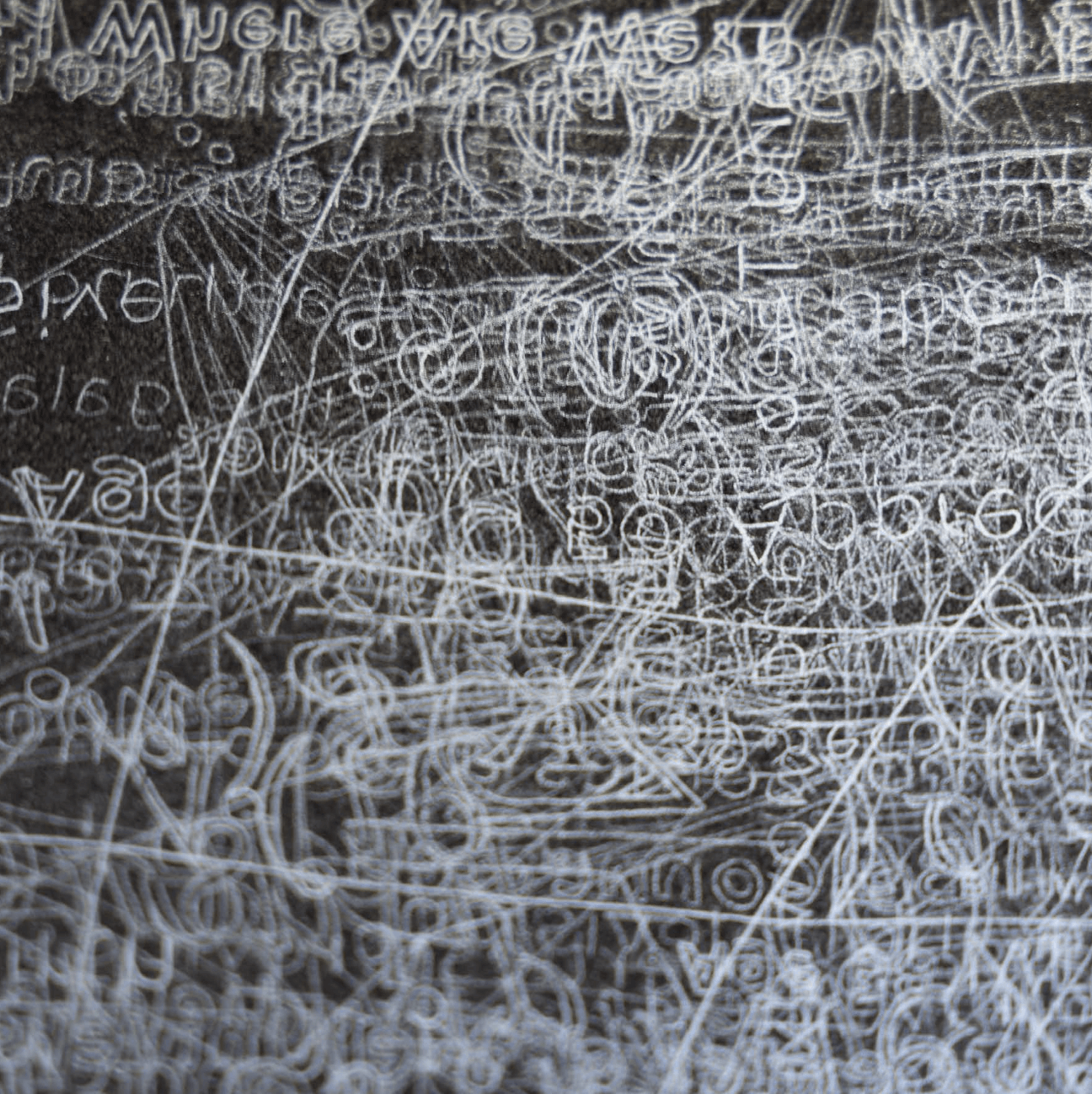

TS: One block away at the entrance of the Minnesota Street Project building, one of our main sculptures The Tree of Knowledge—will be installed. It’s a 10,000-pound cross-section of a eucalyptus tree. We spent over a year distilling the major questions in humanity’s quest for knowledge, and distilled them into different branches: science, technology, humanity, morality. Then I burned them into the wood with pyrography—writing with fire, like a pen with a hot tip.

Then one block away at di Rosa’s museum, there is a a large-scale graphic of The Tree of Knowledge, along with all of our tree sculptures.

In addition to Ken’s big projection—Speculation Abhors a Vacuum (like nature abhors a vacuum)—there’s also a new work called Gravitas. It’s a time-based, participatory pendulum: a large-scale swing set with tree-ring seats. On the far left, in the past: “The world before you were here.” The next: “You were here,” to think about childhood. The center: “You are here.” On the right: “You will be here.” And at the far edge: “The world when you are no longer here.” That’s a new work we’re excited about.

And Ken, you have the new—do you want to talk about Acknowledge and ReBloom?

KG: Great. Acknowledge is about a tree you feel connected to—maybe outside your window—but you rarely learn its details: its history, its species. This project lets you go out, take a picture of the whole tree, a picture of a leaf, and measure the circumference. With that information, AI tools can determine the species, approximate age, and we know your zip code. All that gets put into a timeline—like a mini tribute.

TS: And a history of what happened in the area.

KG: Right. It describes what the tree has witnessed. It’s textual, and it also generates idealized images of the tree through AI. We’re working on a video version using newer AI tools. Anyone can submit a tree and the info, and it generates the tribute.

I’m also showing a piece from a few years ago related to the show: a video live land art piece ReBloom. We take seismic data from a seismometer—live data streaming from the Hayward Fault—and use it to trigger images on the screen, giving you a way to connect directly to the movement of the Earth.

TS: And the curator, Twyla Ruby—she’s amazing—selected some key works from our careers. She’s selected Ken’s piece Bloom, which he’s updating into ReBloom that Ken just mentioned. She’ll also have Dendrofemonology: A Feminist History—my first large-scale tree-ring timeline. There will also be a large-scale lightbox called Roe V. Wade

So it’s a much more expanded version of what we had in LA for the Getty PST exhibition with, new site-specific works related to San Francisco and the Bay Area, key works from each of our careers, and Twyla has also curated a companion show in conversation with ours, called Counter ClockwiseThe di Rosa a museum space in San Francisco is really beautiful

HL: “Expanded” is impressive, because what you’ve described is incredible: the AI component, the tree tribute, the swing set that ends with “the world when you are no longer here,” the geology and the movement of the earth. Beyond the exhibition, there’s also robust programming—some coinciding with International Women’s Day on March 7th, a kickoff party, and more with di Rosa Can you talk about the programming?

TS: I love creating events. Art—whether a film screening or an art event—is a chance to bring people together, have a conversation, experience something together. Especially in this world of screens, bringing people together in person is powerful.

We have a lot of programming: the opening on the 22nd in the evening during SF Art Week. Artist-led tours and talks on the 24th. A Jewish-focused event on February 1st for a little-known holiday we think should be more known—“A Birthday for the Trees,” a whole holiday celebrating trees, which fits our show perfectly.

Ken will be in conversation with a curator from the Whitney Museum Christiane Paul on Art, Artifice & AI on March 12th and then n environmental-focused event with Krista Tippett and The Long Now FoundationMarch 26th.

Then our closing night celebration dance party that’s a benefit for di Rosa on April 11th. Info to RSVP & Tickets can be found at ancientwisdom.art

The concept is: different parts of the show—feminist history, AI art, and more—so we’ll host events that speak to each component and invite partnering organizations. We’re local, so it’s fun to have the show to our hometown, especially since so much of it was inspired by Muir Woods and AI happening here.

KG: And I should mention: I’m represented by the Catharine Clark Gallery, right up the street from the new di Rosa. She’ll feature a video piece of ours—from the LA show in her gallery on January 10th, before the show opens, Speculation, Like Nature, Abhors a Vacuum on the Ed Ruscha inspired artwork that will be in her media room.

TS: It’ll be the—Original work from LA—focusing on 4 LA Streets.

KG: Right—more directly related to the Ed Ruscha idea. And at the same time, we’ll have the San Francisco version—the San Francisco streets piece—in SF.

HL: Wow, I want to pull things full circle. We talked about Jewish wisdom and the idea that it can be a framework for thinking about AI. Ken, in your TED Talk “Telegarden”,” you share a life lesson: always question assumptions. You both kept returning to that today. What assumptions are you questioning now?

KG: One of the nice things about being in a university and being an artist is that you’re encouraged to question assumptions. I’ve liked doing that since I was a kid—I was rebellious, and I liked rebels. That’s part of what attracted me to the Bay Area: a history of beats, hippies, counterculture protests. I like pushing back.

When everyone thinks one thing, I ask, “Is that really true?” Often, it isn’t—and we can invert conventional wisdom. Right now, for example, there are a lot of expectations around robots that I’m pushing back on. People assume they’re going to take over and all these things, and I disagree. I also have thoughts about where AI will make an impact and where it won’t.

At root, Tiffany and I both deeply value the human experience—the physical world, nature. Those are things we hope won’t be affected by new technologies.

TS: In fact, it almost makes you want to double down on the human experience. That’s why we’re having so many events at the show: physical art with a visceral, embodied component. We do have AI in the show, but it’s AI that highlights nature—helps you understand nature more. It helps you see San Francisco through a bird’s-eye view of trees and shade inequities in different neighborhoods.

The show explores those tensions. Questioning assumptions has been central to my documentary style since my early days at Berkeley—questioning the traditional narrator in educational film and messing with that. And Dendrofemonology: A Feminist History challenges the patriarchal timeline you see at Muir Woods or any national park—rethinking it and making it feminist.

One piece we didn’t talk about, Ken, which is one of our favorites, is Abstract Expression: a seven-foot redwood slab where we distilled the most important mathematical equations throughout history.

KG: Right. We wanted to do a history of science using only equations—no words, just numbers and symbols.

TS: And that piece also questions how we expect to read a timeline. People ask, “Why aren’t there any words?” And as Einstein said “equations are like poetry.” A lot of the work is about questioning, rethinking, and looking at things in a new way—through trees.

Hugh Leeman: Ken Goldberg, Tiffany Shlain—thank you both. It’s beautiful to learn from your creative, collaborative process. And it’s incredible to hear your optimism and the ways you’re thinking and questioning assumptions. Thank you.

Tiffany Shlain: Your questions were amazing.

Ken Goldberg: Yeah, Hugh, it was great talking with you.