David Deweerdt, Excessive Body, Ryan Graff Contemporary

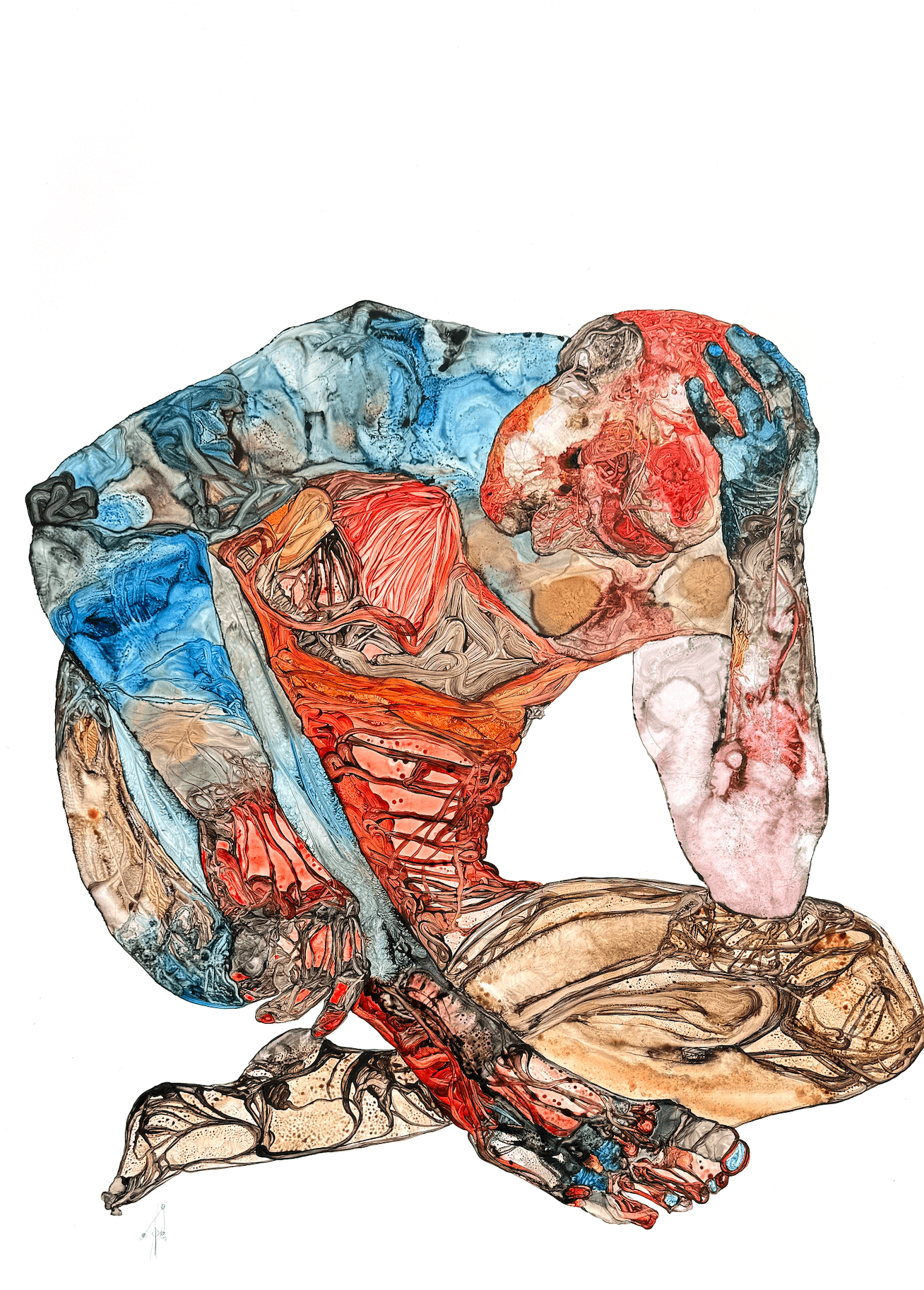

Left: Untitled (16), acrylic and ink on Mylar, 100 x 70cm , Right: Untitled (17), acrylic and ink on Mylar, 100 x 70cm

A psychiatrist friend recently introduced me to the concept of hedonic neutrality. Briefly, and possibly over-simplified, to be hedonically neutral is for one's own emotional state to be in its natural balance. It does not mean one is emotionally neutral, as for most people, their natural emotional state would be slightly positive. Instead, it's an equilibrium within oneself given all the conflicts we face from both within and, especially, from outside ourselves.

The 17 pieces in David Deweerdt's current exhibition "Excessive Body," on display now at Ryan Graff Contemporary, are monuments to gross hedonic imbalance. Of the figures represented, their inner torture is obvious, their psychological pain wrought carefully and boldly for all to see. With an ingenious combination of acrylic paint and ink, bold stylistic contrasts that reside immediately beside each other in every piece, and precise control over color and anatomy, Deweerdt shines a bright light: on our body insecurities, toward the cultural factors that throw us all out of balance, and into the depths of everyone's unique versions of emotional distress and self-hatred. His artist statement explains that Deweerdt uses his work "as a way to provoke reflection on 'normality,' exclusion, and the relationship we have with our own bodies," and his specific talent combines with daring technical choices to find his observations fully realized.

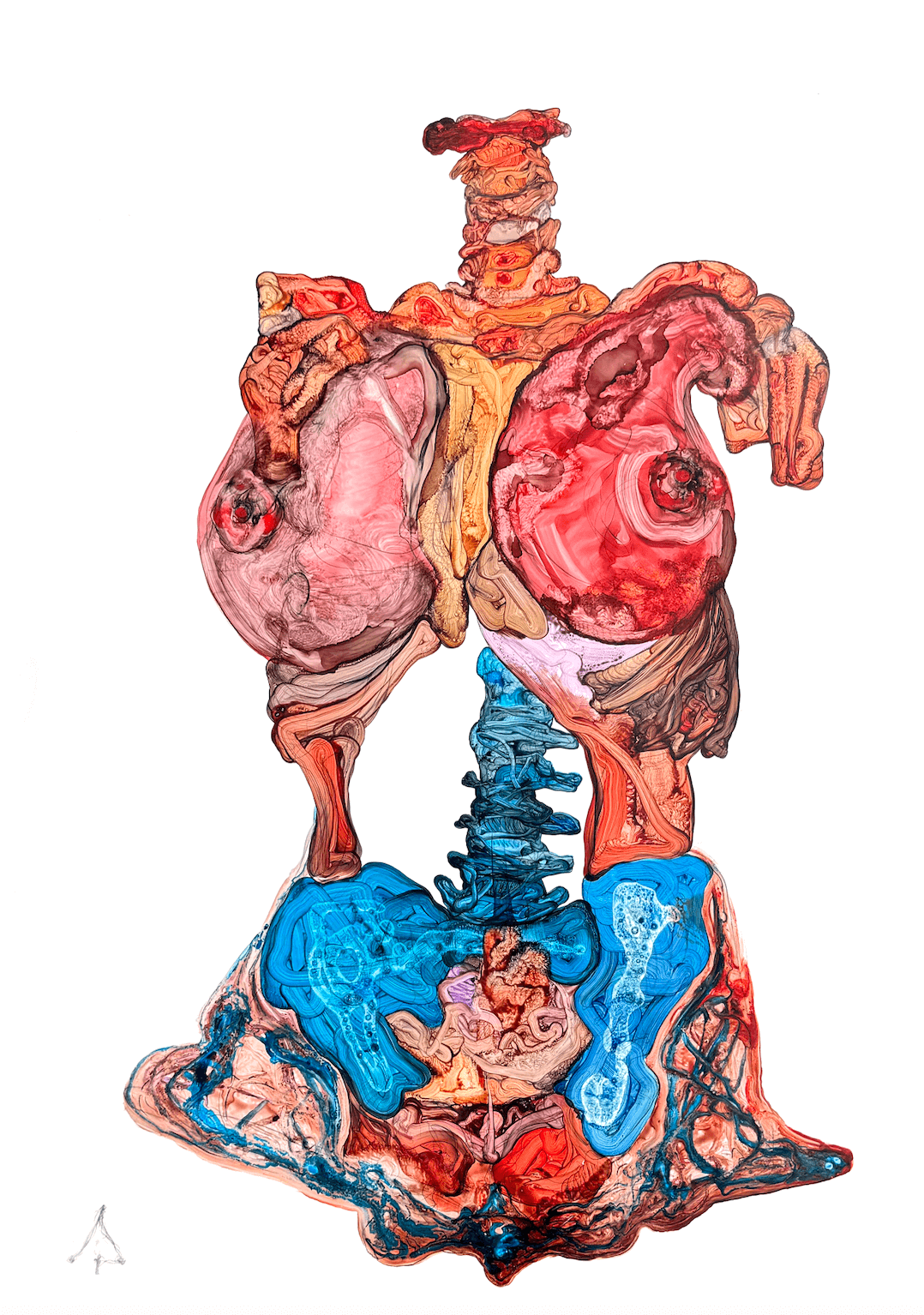

These works are not simple illustrations of pain itself: they are heat maps of the human soul. Not unlike a weather map showing temperature ranges across a country, we have bold, dark, visceral reds to illustrate pain points, sporadic but highly intentional uses of blues to show areas of relief or at least momentary calm, and combined with composition and subject matter, we can use these "maps" to read exactly what it is that so pains these individuals. A majority of the pieces are devoted to feminine figures, and often we see their pain reflected in their skulls, their breasts, and their reproductive organs. Deweerdt has in the past frequently worked with feminine figures, examining what he calls the "paradox" of life as a woman: if a woman is conventionally physically attractive or focuses on her appearance too much, as society encourages, then her humanity is so often ignored, but if a woman is highly capable and/or deemphasizes their appearance, their abilities and talents are so often dismissed. Such no-win situations create the deep emotional pain that so fascinates Deweerdt.

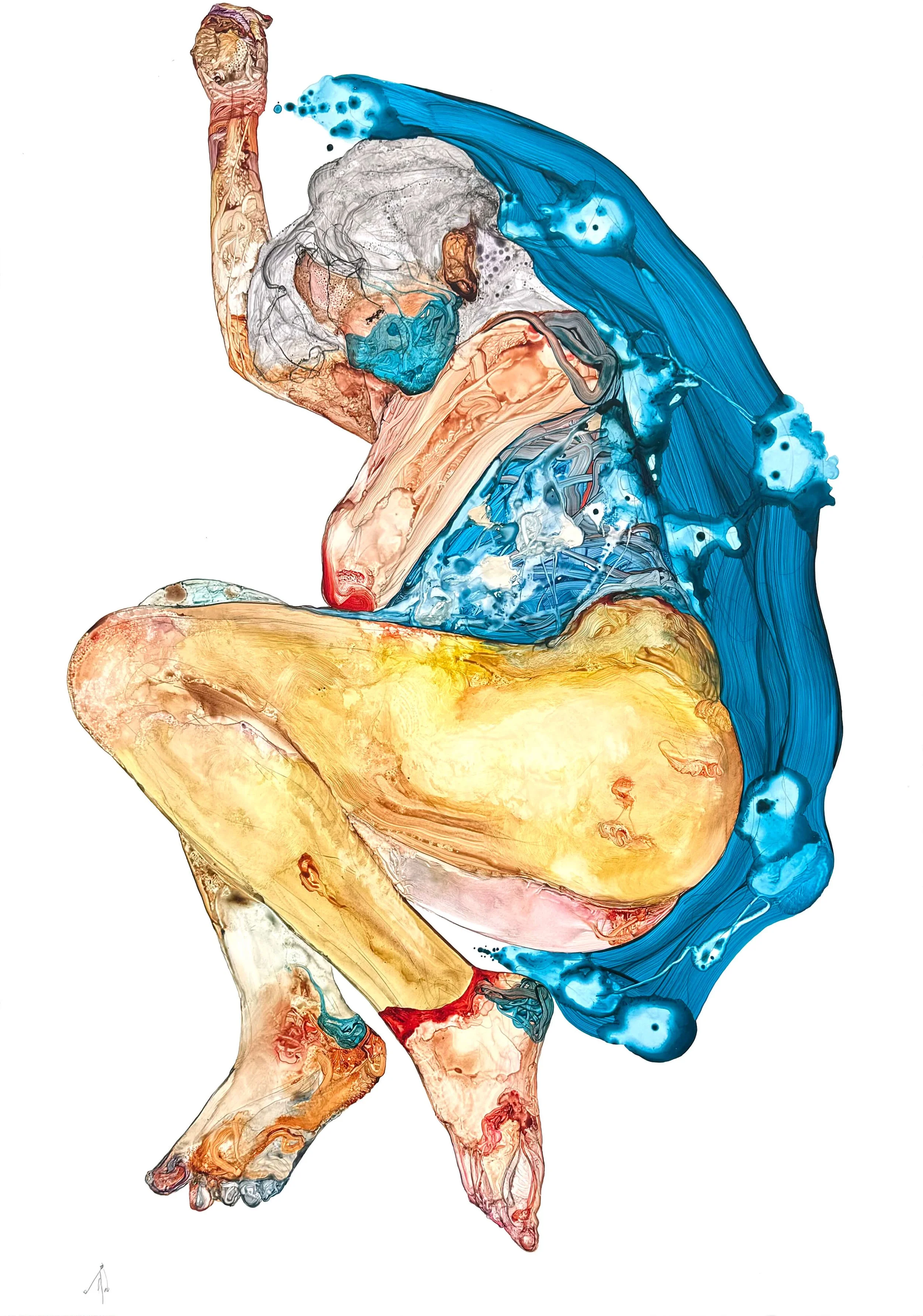

Left: Untitled (07), acrylic and ink on Mylar, 100 x 70cm , Right: Untitled (02), acrylic and ink on Mylar, 100 x 70cm

In this new collection, Deweerdt has expanded beyond only the feminine. We see a hunched over figure of indeterminate gender in Untitled 07, viewed from behind as if their hands and feet were bound, with deep maroon and hot golden wrists, the bottoms of their feet appearing bloody and raw: the figure so reminiscent of the overworked and underpaid, constantly suffering physically and emotionally from the rigors of working their body past its breaking point. In Untitled 02 we have an overweight male, headless, pictured from the side as one might judge their body fat in a mirror, the whole of the figure a mix of colors not unlike those of a raging fire: a stand-in, perhaps, for all men who feel less-than, trapped in what they see as a sexually unattractive body. Deweerdt also presents skulls deformed, meat hanging in slabs, and so often leaves, feathers, and other adornments that hint that much of our pain may come from our modern disconnection with nature itself.

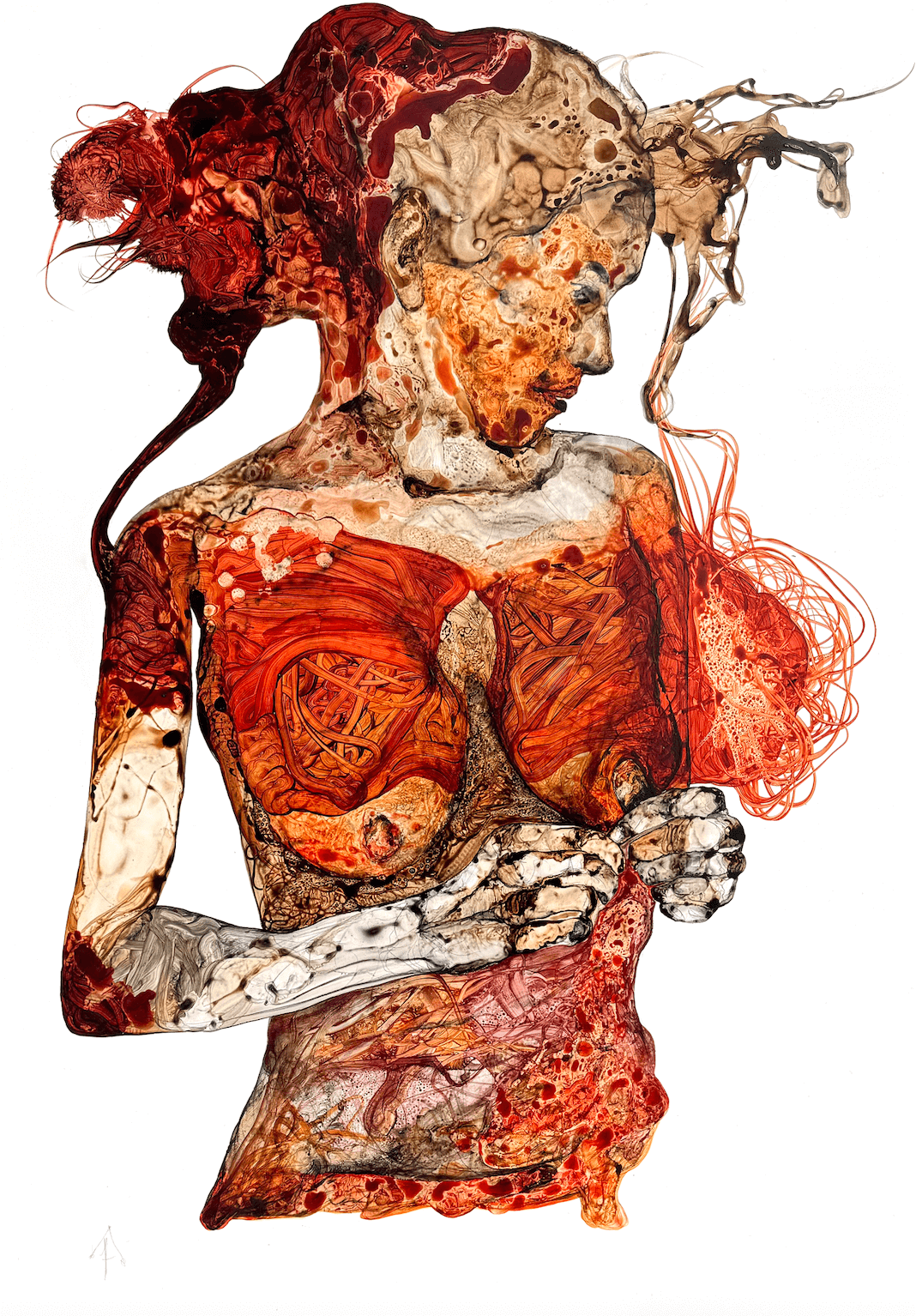

Left: Untitled (13), acrylic and ink on Mylar, 100 x 70cm , Right: Untitled (03, acrylic and ink on Mylar, 100 x 70cm

But the most powerful pieces remain those where women are the central figures. A standout piece of the show is Untitled 13: a woman standing pleasantly, maybe slightly reserved, but the emotions depicted betray that calm. Areas of neutrality – collar bones, forearms, and the front half of the brain, responsible for things like personality and cognitive thinking – are rendered in a bone-like color...while the rest of her simply burns. Her hair, her breasts, her midsection are scorching hot, both rage and doubt leaping off the wall, the contrast between who she is and how she feels made violently evident. Untitled 03 presents a woman's torso only, with almost every bit of flesh removed save for breasts and reproductive organs. While bones are painted in a peaceful blue, the entirety of the flesh is represented in swirling illustrations of chaos itself, of disparate shapes and colors and artistic styles all combining into an unmistakable portrait of the most basic of women's struggles: do they not hold value beyond their bodies, or beyond being baby-makers?

Left: Untitled (04), acrylic and ink on Mylar, 100 x 70cm , Right: Untitled (15), acrylic and ink on Mylar, 100 x 70cm

Gazing toward the male, though, also serves the theme. Untitled 04 presents a man kneeling over a small body of water. Interestingly, his entire body reflects a persistent pain, but his eyes and the area immediately behind them are rendered in nearly the same calming, peaceful blue as the water. The immediate thought is toward Narcissus, so enamored with his own reflection...and that leads to what may be the piece's ultimate revelation: that too often today's man is full of emotional pain, yet fully at peace with the person they are and the opinions they hold, such that peace is only found in their own reflection. In the modern era, we can find such "reflections" in the worst of online echo-chambers, or an unfounded self-confidence that is, to a fault, unshakable. This man forsakes understanding his pain for the calm of how they see themselves, a problem all too common throughout history, but especially now, as we face new generations of emotionally immature men raised on the internet and its endless negativity and cruel othering.

Every piece in the show is striking, to Deweerdt's great credit, but here we must shift our perspective from the thematic elements to acknowledge the foundational components of these paintings. Each piece is done on a 100 x 70cm Mylar sheet, its natural, bright-white, and perfectly smooth state serving as a high-contrast background that canvas or panel could never achieve, but it also leaves no room for error. One cannot paint over a mistake so easily on Mylar, meaning that each of Deweerdt's moves, every bit of ink poured or paint brushed, must be perfect. Given what appear at first to be free-form or almost wantonly diverse techniques, it's borderline miraculous that the pieces come together so smoothly.

To that idea: I lingered in the gallery on opening night and, late in the evening, saw a woman position herself at the edge of a painting, examining it from an extremely oblique angle. I said, "I did the exact same thing...looking for brushstrokes, right?" And she was. Because from a technical standpoint, these works are bewildering. There are no covered mistakes, no accidental layering of paint, no spilled ink, no texture, no imperfections: we both remarked simultaneously that the pieces almost looked like prints, they were so clean and flat. Considering there is no room for error, the technique, planning, and skill behind every single application of color is simply stunning. Deweerdt's style is a tightrope walk with no net; in Excessive Body, he laughs in the face of that danger.

Further, in many pieces, there's an intentional disregard for the "rules" of composition, opting for a deliberate command of viewpoint such that, much like in film or photography, the framing itself helps to convey Deweerdt's message. Figures are rarely centered on the panel or aligned to traditional focal points, instead they're pressed into corners, cut off by the boundaries of the panel, or untouched negative space is wielded like a weapon: the bright white of the Mylar at once supporting the art, its high-contrast nature allowing the colors to scream off the piece, while also disrespecting the figure, forcing us to view the subject as askance and obtuse, in furtherance of their pain.

Left: Untitled (05), acrylic and ink on Mylar, 100 x 70cm , Right: Untitled (14), acrylic and ink on Mylar, 100 x 70cm

One must view the body of work in person to truly appreciate how the art itself works so well: whether the planning was incredibly precise or Deweerdt works in some sanctified level of flow state, I can't say, but among the dozens of techniques employed there's only precision to be found, and every bit of imbalance and contrast fits together in service of the larger whole, one that I hope – and I would suspect Deweerdt would as well – inspires viewers to look inward, to examine and resolve their own internal conflicts, freeing themselves from their pain.

"Excessive Body," then, is two things. It's a sobering look into the excessive pressures and psychological attacks we face for simply being alive, and it's an excessively impressive body of work. It's rare to see an artist both fully realize their emotional intent while also showing such command of such disparate and demanding techniques, and my appreciation for the work has only grown in the days since the opening.

The show runs through February 7 at Ryan Graff Contemporary, 804 Sutter St., San Francisco.