Tabled: Recently Acquired Contemporary Still Lifes, Crocker Art Museum

Through February 1, 2026

By Carlos Alcalá

Still life. It is nearly impossible for me to think of the idea without envisioning a carefully arranged and realistic bowl of fruit on a table. Perhaps such a painting (Isn’t it always a painting?) will show a ewer, a sheet of music, perhaps a pheasant or rabbit hanging nearby. Even as still life has been redefined by Picasso, Morandi, Cezanne, Thiebaud, and others, we hold on tightly to certain preconceptions.

The pieces in “Tabled,” the current installation at the Crocker Art Museum, do a service by helping to loosen that grip. “Some are almost not still lifes at all, and yet they are,” said Scott Shields, chief curator for the museum. Indeed, some are without fruit, without tables, without paint, all to great effect.

An Te Liu (Canadian, born Taiwan, 1967), Wúxiàn II, 2025. Cement, 46 1/2 x 6 1/2 x 6 1/2

in.

Shields pointed at An Te Liu’s sculpture Wúxiàn II. At first glance, it looks like a brutalist column in miniature. Closer examination reveals an assembly of molded concrete in the shape of take-out food containers, the kind usually made from a single piece of folded cardboard.

As fodder for a contemporary table, an ewer is an anachronism. A take-out container is on point. You may have one in your refrigerator. Here is the still life we didn’t know we needed. Also in a modern vein, yet quite different, is Peonies: Symphony, a watercolor by Gary Bukovnik. While its flowers may seem rather traditional, and Bukovnik’s style is hardly revolutionary, the stems in the glass vase are bunched with rubber bands – an ultimately modern touch. Moreover, they are without a table. They float in white space.

Enrique Chagoya’s cheeky sculpture, The Enlightened Savage/Cannibul’s II, also fits our era, an age of satire. With his characteristic biting, issue-inflected humor, Chagoya’s work consists of 10 soup cans and their packing box. They look like Campbell’s, but they are Cannibull’s. They remind the viewer that art is cannibalized by the modern aesthetic industrial complex. Soups like “Curator’s Liver,” “Museum Director’s Tripe,” “Cream of Dealer,” and, yes, “Critic’s Tongue” implicate the parasites who feed off the artist’s work. Each has a financial interest. Museum and gallery visitors seem to be the only ones not in hot soup with Chagoya.

The piece owes an obvious debt to images from Andy Warhol’s Factory, but Chagoya approaches the production aspect differently. Each of his can labels acknowledges collaboration with Trillium Press, a lithographic printer. This, he proclaims, is not the work of a solitary genius.

The contributions of Chagoya, An Te Liu and Bukovnik are table-ready, so to speak.

So is Frank Romero’s Natura Morta with Pingo y Calavera, an oddly trilingual title with ambiguous meanings. Natura Morta literally means “dead nature” in Italian, but it is also the term for still life in that language. Pingos are what Romero calls some playful ceramic figures he has created. There is one of those depicted on the colorful textile-covered table in the painting. But “pingo” has other meanings, too. It can mean the devil. A calavera is a skull, a traditional element of still-life painting in the genre known as memento mori, reminding the viewer: “Remember you must die.” The calavera is also a decorative and spiritual element of Mexican life, with artistic antecedents going back to pre-Columbian times.

It is ripe with references to the past, but vividly alive.

Almost directly across from Romero’s painting are two works – one by Gordon Cook, another by Robert Rauschenberg – that represent a sub-genre of memento mori known as vanitas. Vanitas literally means emptiness in Latin. Vanitas paintings of old were created to symbolize the vanity or emptiness of life.

In the case of Cook’s oil painting, Cardboard Box, the emptiness is literal – a still life of an empty can and empty box on a shelf. Cook, a contemporary of Wayne Thiebaud, echoes Thiebaud’s affection for Giorgio Morandi’s still life style.

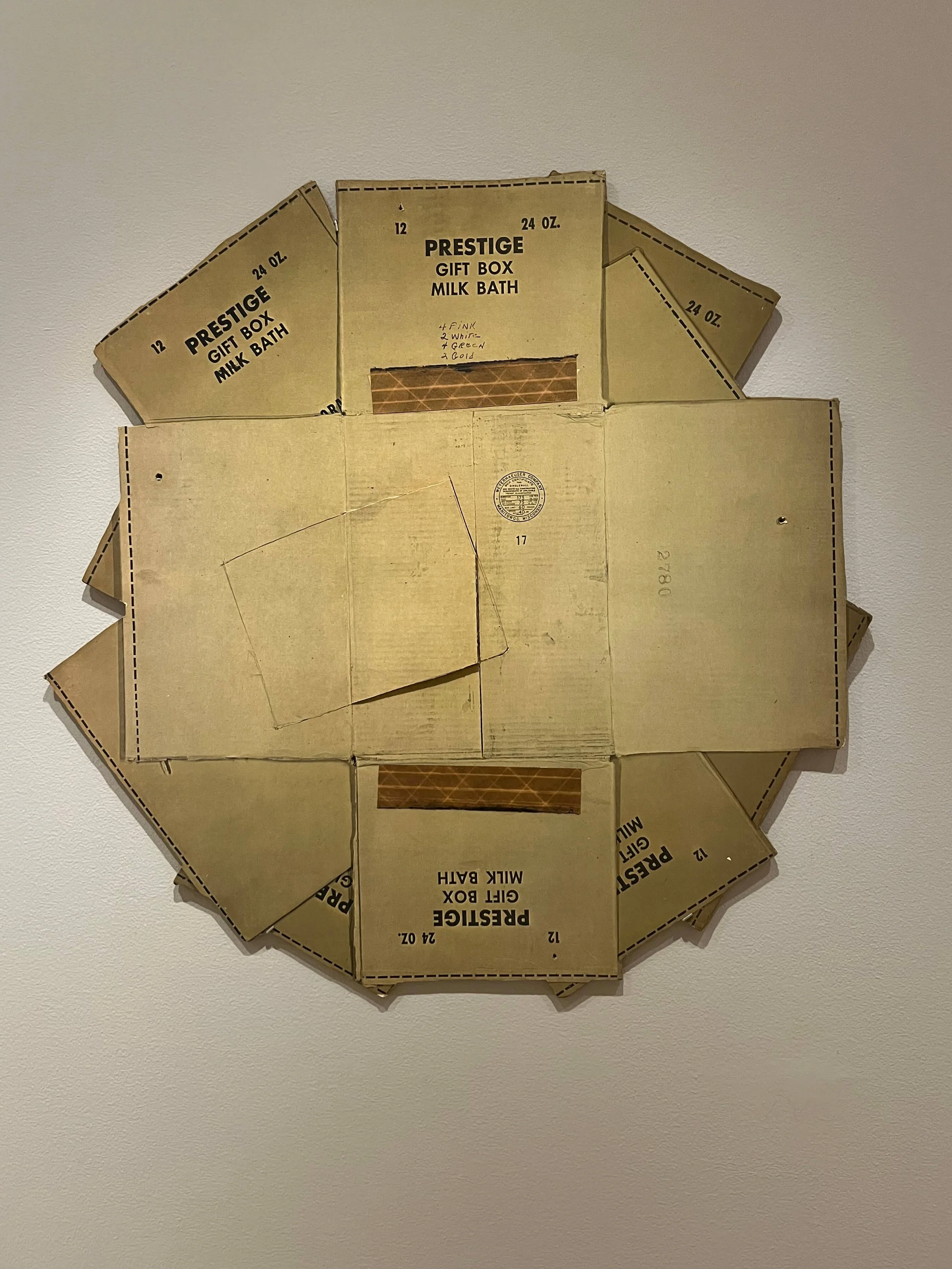

Adjacent to Cook’s painted box is what appears to be an actual flattened cardboard box, Robert Rauschenberg’s Cardbird VII from 1971, the oldest piece in the installation.

In the same year Rauschenberg worked on his Cardbird series, he produced another series, Cardboards. For the latter group, the artist found empty, flattened boxes and folded, stapled, and manipulated them to create relief collage sculptures. Cardbirds, by contrast, are pieces of new corrugated cardboard, screen printed and cut, with tape added, to mimic flattened empty boxes.

In addition to being a brilliant conceptual piece and a literal allusion to vanitas – emptiness – Cardbird VII is a terrific example of the elevation of everyday materials – not just everyday subject matter – to create art. Fine art does not equal marble and oil paint.

Another piece of vanitas is Emilio Villalba’s painting, Home Again. Classic vanitas paintings were created using common objects in allegorical fashion to symbolize life’s transience. In some cases, paintings allude to life’s pleasurable activities and possessions.

Home Again is a brilliant and vibrating welter of everyday objects, many of which have no place on a still life table, from a car and basketball hoop, to shopping baskets and carts, aside milk crates, and footwear. They float, as though weightless, on an orange impasto background, along with smaller items – scissors, beer bottles, a tissue box – and miscellany, including disembodied legs and a hand.

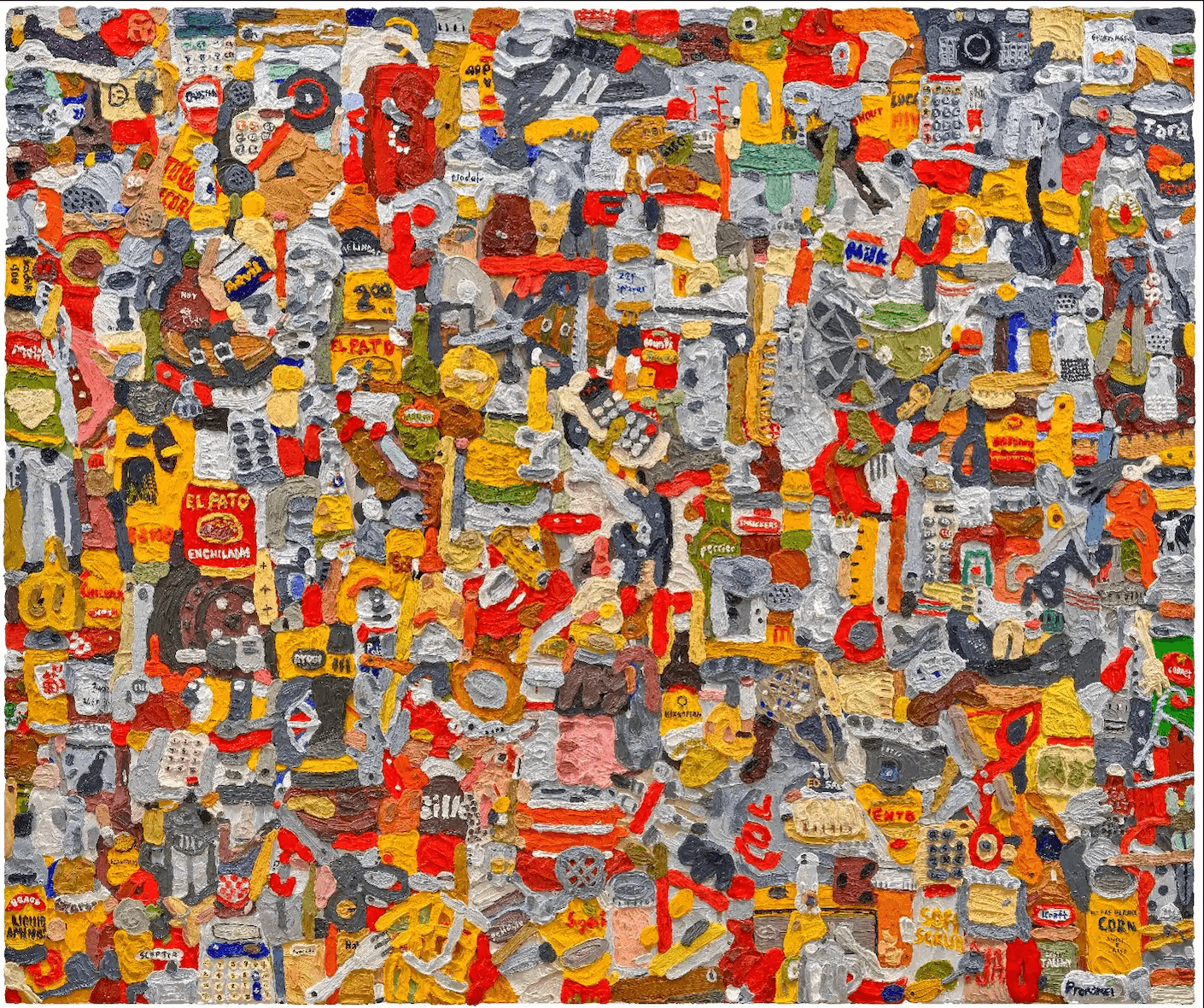

The painting is among Shields’ favorites. Elsewhere in the museum, he showed off another Villalba acquired by the museum, Everything is Something 5, a piece with paint so heavily applied that the depicted objects seem to physically push one another back toward the canvas. The oil paints had not yet dried when it came into the museum, and their odors still emanated, Shields said. He leaned in to see if he could still catch a whiff.

In Home Again, many objects allude to vanitas themes of pleasure, transience, and the modern counterpart: empty consumerism. Here and there are other, more obscure symbols. Every object must mean something. Villalba seems to hint at that idea with the title of his other painting: Everything is Something 5.

The 25 works that make up Tabled are not there to fulfill a high concept. This is not the kind of show conceived years ahead. Tabled is mainly an opportunity to showcase some of the museum’s recent acquisitions.

“When you get new things, people want to see them,” Shields said. The Crocker has acquired 600-1,000 new works per year in recent years. “Tabled” reflects curators’ recognition of a still life thread running through some of those acquisitions. Even as Tabled was being installed, the museum acquired Wúxiàn II and added it to the others in the gallery.

After all, it was new, people would want to see it, and it fit the “still life” rubric. We can be glad if it stretches our imaginations beyond the familiar concept of fruit in a bowl.