Jiabao Li

Jiabao Li is an artist and associate professor at Northeastern University whose work explores climate change, interspecies co-creation, humane technology, and human perception. She works across wearable systems, robotics, AR/VR, performance, scientific experimentation, and immersive installation. In her TED Talk, she revealed how technology mediates and reshapes our experience of reality. Jiabao has received numerous honors, including Forbes China 30 Under 30, the iF Design Award, Falling Walls, NEA, STARTS Prize, Fast Company, Core77, IDSA, A’ Design Award, Webby Award, and Outstanding Instructor Award. Her work has been exhibited internationally at the Venice Architecture Biennale, MoMA, Ars Electronica, the Exploratorium, the Future of Today Biennial, Milan and Dubai Design Week, The Contemporary Austin, Ming Contemporary Museum, and the Museum of Design. Her academic papers appear in SIGGRAPH, CHI, ISEA, IEEE VIS.

The following are excerpts from Jiabao Li’s interview.

Hugh Leeman: Artist, technologist, professor, entrepreneur—these are all elements you bring together through your creativity, curiosity, and ambition. When you were growing up, how were these things fostered and by whom?

Jiabao Li: I think the engineering part came from growing up in China. You know, all the Asian parents want their kids to be in the STEM field. My dad signed me up for math specialty classes—I competed in Math Olympiads without my consent. So I did a lot of Olympiad math competitions at the time. He's an engineer, and I grew up in a family surrounded by engineers. That's where that element of me comes from.

The art and design really began when I first came to Singapore as an exchange student in middle school. I got exposed to so much contemporary art, and I was like, "Wow, this is something I want to pursue." That opened up a new door for me. I studied electrical and computer engineering as an undergrad, thinking I would do something more on the design side together with engineering. Later I entered Harvard Graduate School of Design, which again opened me up to the possibility that art and tech can be a really interesting thing to pursue.

Throughout my studies and later my career, I really don't differentiate a lot between these titles and tags. As for entrepreneurship, I got a lot of influence from my uncle who does environmental engineering entrepreneurship. Throughout college I was also in various entrepreneurship programs and founded startups now and then. This is the third one now—my third startup. It's been throughout my whole journey.

HL: Your family has clearly been this really important part of your influence, from all the people you've just mentioned. I want to focus here a bit more on your mother and turn the attention toward a project—the heart you created for your mom, who was diagnosed with heart disease. You grew an artificial heart using stem cells from your menstrual blood. The project blends this deeply personal idea with biotechnology in a bold way. You said at the time, quote, "My mother created my heart from her womb, and I reciprocated by giving her a heart grown from menstrual blood stem cells from my womb." End quote. What were the conversations with your mother like during this project?

JL: She had a heart attack about three years ago now. Unlike a lot of men's heart attacks where you have the sudden event, for females it's often like back pain here and there—it goes away and then comes back. A lot of medical education we see in this world is very much based on men's symptoms. In the movies we see heart attacks portrayed as very sudden—you fall down. So she went to the hospital three times. She had three events but didn't know they were heart attacks. She thought, "Okay, I'm just tired." There's a huge education gap there.

That event inspired me both for this work and also my company, which I co-founded, called Endless Health. It also focuses on cardiovascular health. That's more on the "let's go out and try to change the world" side. The artwork started with menstruation work—sequencing the proteins inside to find out what you can tell from menstruation that can be a new biomarker for monthly health testing for people who menstruate. It went from growing a clitoris from menstrual stem cells to growing a heart.

Throughout the work—I mean, we got to talk about this so much more—I took her on a photo shoot, which was part of the work. For all her life, she's been spending time for others, taking care of others. It was me before, and then her parents, and right now it's my daughter. She hasn't really had time for herself. Just taking her on this photo shoot for this work—she got to dress up, have makeup, and we had different photo shoots. It was a really nice thing for her.

She never really accepted that I'm an artist. When I say I'm an artist technologist or creative technologist, she always just refers to the creative technology part and even tells me not to tell other people I'm an artist. For some reason there's some bias there. But throughout this work, she started to have more understanding of what I'm doing. Again, she's more interested in the science part of it.

There have been some really lifestyle-changing parts through both this work and the company. She's adopted such different lifestyle habits. I'm on her about that every day, and she's gained so much knowledge in the field and knows what to do to prevent this from happening again.

Let me add one more thing. I just did a TEDx talk where I went much deeper into this: because of China's one-child policy, a lot of girls got aborted, given away, or abandoned. I almost got aborted after they found out I was a girl, but my mom was the person who saved me. She was like, "No matter what, I'm going to have her. I'm not going to abort her because she's a girl." When there were so many people pointing fingers saying a girl doesn't deserve all this education, doesn't deserve all this money put into her education, she shielded me from all that and really spent all her time, finances, and effort in educating me well. So this work is a really touching one that allowed me to be so much closer with her through art practice, which we don't talk about very often.

HL: That's very touching. Thank you for sharing that, the TED talk, and the connection with her. What an incredible testament to your mother's love from before you would even have been conscious of this. Beyond the artwork—and we've talked just a touch about entrepreneurialism, technology, and engineering—you're an activist as well, and that takes on a role in your art through environmental issues, gender norms, freedom of expression. You once made a mask out of your own shaved hair to protest the way women were portrayed during COVID in China. Can you share context on this project for those who may not understand the depth of this, and tell the stories of the conversations that came up around this with other Chinese women?

JL: At the beginning of COVID, hospitals wanted to show how heroic the nurses were and how they were sacrificing everything to fight COVID. So they filmed these health workers shaving their heads. They all had beautiful hair—very young females—and one by one they shaved their heads. They were crying in the video, and they had music that made it very dramatic as a way of showing, "Okay, they're sacrificing all this."

Cutting hair is a big thing in Eastern culture. Cutting your hair and tying it with somebody can mean "I'm your forever friend" or "I'm married to you"—it's a very symbolic thing. They used this as propaganda to show, "We can all do this, sacrifice ourselves in fighting the pandemic." It was really using female bodies for this propaganda message. At the end of the video where everybody was taking a photo together, the only person who had hair was a man standing in the middle of them.

So I took part of my hair, kneaded it into a mask, and then took that photo—like I'm always muzzled there—with that mask with that little twist at the bottom.

Another layer of that is also that it was a time when there was so much censorship going on. Things were constantly being deleted. People who reported cases, or even Dr. Li Wenliang, who was the first person who shed light on this virus going on—his voice was being muffled. So having a mask was also talking about that.

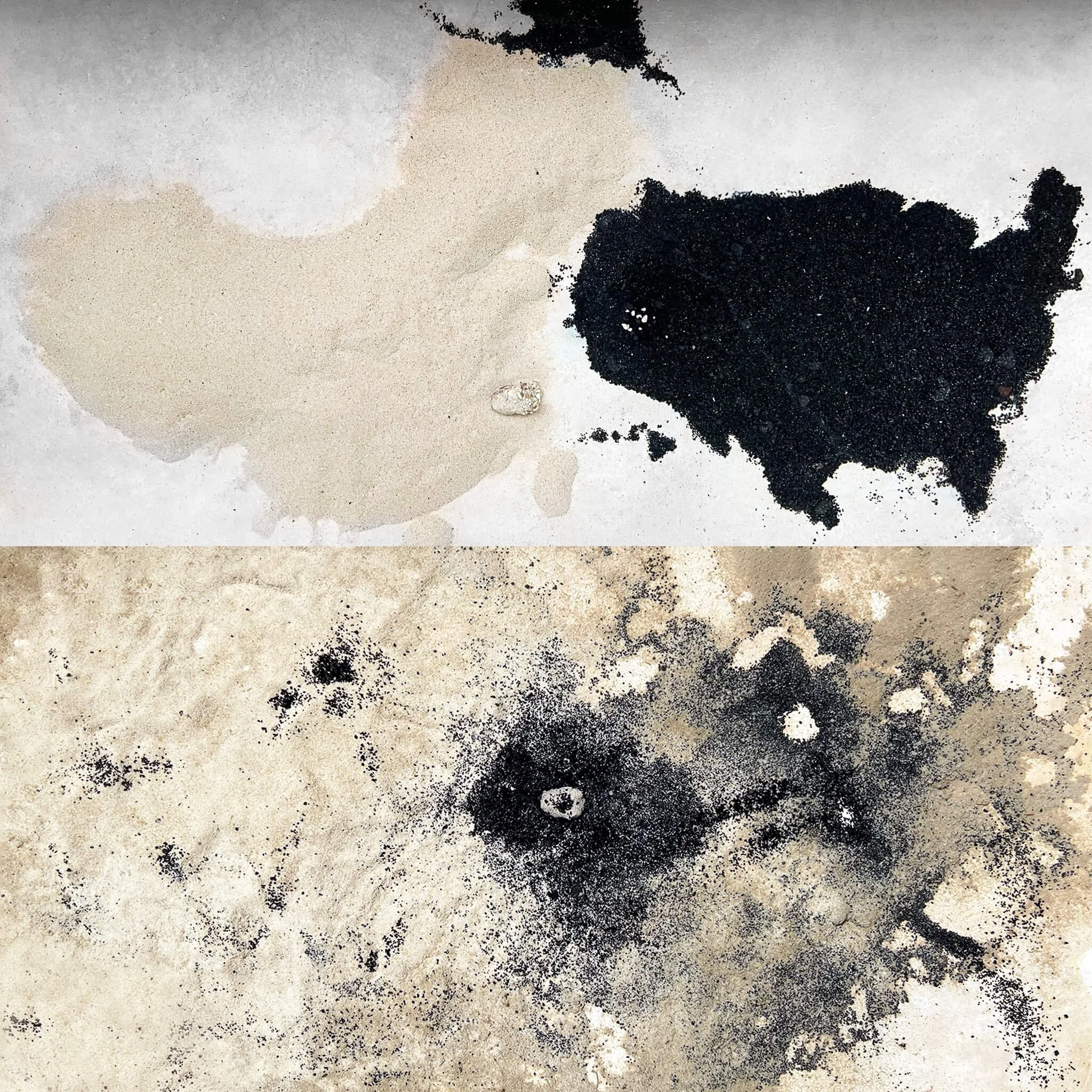

HL: Wow. I want to come back to this idea of censorship a little bit later, but perhaps we can zoom out a little bit here and look at Chinese-US relations. You've spent years living between China and the United States. You once described yourself as, quote, "moving between China and the US, carrying the baggage of two cultures, trying to assimilate and trying to blend in," end quote. This is similar to the squid in your project that camouflaged itself in black and white sand. Can you talk about the project "The Squid Map" and how living between two cultures has influenced your art and perspective?

JL: I did a self-initiated artist residency at Kewalo Marine Biology Lab in Hawaii while my partner was a scientist researching the bioluminescence of squid. So I hung out in the lab observing the squid. At first I was fascinated by their symbiosis with bacteria—they can light up to not cast shadows on the ground so predators won't see them. They appear as moonlight. I thought I would do something with that.

But after months of spending time with the squid observing them, I got really fascinated by their way of camouflaging. That was also a time when a lot of people couldn't go between countries because it was during COVID. So I was thinking about how I'm being blocked, I can't really go through these country borders, but the squid living in the map that I constructed can freely go between without borders and also freely reshape the borders and the map.

I collected white and black sand from Hawaii Islands and made them into the shape of China and the US. Then the squid lived there, swimming in between, carrying the sand and spreading it around, reshaping those borders and traversing the country border without a visa or passport. That's one way it's about reminding me of myself as an immigrant going between China and the US.

When you first get out of your country, you really need to assimilate, try to think like the country you're entering, talk like that, feel you're part of them. That's like the squid burying the sand on its body.

That was also a time when we heard "build a wall." We build walls between borders and between countries that can block natural animal migration. For example, the wall Trump built at the Mexico border—some of the designers designed small holes for animals to pass through, but when they actually built it, they blocked them. So not only do humans not get to see each other across the border, but the animals don't either. We don't really think about them through these scenarios.

After one month, you see the difference between the before map and the after map. This border, this map that we've fought wars over for many years—in the eyes of the squid, another non-human species, it's drawn in very different terms.

HL: You did a show in China and ended up having to explain to the censorship police the show's merits so that it wouldn't be shut down. Can you talk about censorship of art in China and then tell the story of this exhibit and your interactions with those officials who came to see the show?

JL: Censorship in China and how artists get around it is already artwork in itself. There should be a book just talking about this. Sometimes it's frustrating, but it's also getting interesting. There are so many ways you can talk about things that people who look at it understand, but you can get around censorship. People make certain words or characters or encrypt things that people who see it can understand. But even these days with AI and big data, you can't always evade detection.

For art exhibitions, everyone needs to get through scrutiny from the institution—like the museum or gallery itself—and also scrutiny from the city and the government. You first do a round of self-censorship, and then they'll have somebody come and see things.

For me, I was having an exhibition called "Hysteresis," and I showed a work called "Sentient Clitoris: The Pussification of Biotech." I did my translation more focused on the science side, so the work felt more science-oriented. But when you come and check out the work, see the video or see the translation of the video, you know it's talking about growing a clitoris out of stem cells from menstruation blood. It's talking about this gender imbalance in science research and also all the body politics about growing organs out of menstrual blood stem cells.

The officer—I think he's from the cultural bureau—came and was standing in front of a TV that had a screensaver of Botticelli's painting. He was standing there looking at it for a long time, and I was like, "This person looks like the investigator." I told him—he was looking at it very seriously, trying to think about whether he should censor this. I asked if I should turn on my work, and he said, "Okay, yeah." So I turned it on and gave him a tour throughout. I really just emphasized all the science parts—this is research, not too much about the activism or feminism part. So I got away with it. In the end he said, "Thank you for bringing such work with international vision to our city."

Even later throughout the exhibition, which ran for three months, there were people who came and checked. They dressed in normal people's clothes and checked to make sure everything was still like that.

HL: Wow. Thank you for expanding on that idea. I want to take us a bit further to another project from the people's angle and the participants' angle. You did a project called "Say See" in which you made a speech-to-video generative AI system that would transform people's spoken words into very emotional videos that analyzed the emotional tone of their speech. You've spoken about how topics like war and politics came up, as well as sensitive topics in China such as the Tiananmen Square massacre, and how citizens were asking about censorship in their own country. Can you share stories from this project?

JL: When I exhibited in China versus the US, the people who talked to the AI and the videos generated—the content was entirely different. When I showed it in the US, a lot of people shared their personal stories. There was one lady who talked about her whole love story throughout her life to the AI with that sentiment, and it generated a video. She said, "This really got all my memories out—almost like dreamy. It's not very realistic, but it's how memory could feel like."

When I showed it in China—maybe also because there was a particular group of people coming who were so aware of the internet wall and knew this was outside the wall—a lot of questions got asked like, "Show me what it looked like during the Cultural Revolution or the Tiananmen Square." Things that you don't get to see much within the walls of the AI version in China.

I think it's also a reflection that with all these AI models going on that are trained on specific data within that realm—DeepSeek versus Gemini or ChatGPT—the reality you get is very different. Before, we had social media-mediated reality that was prompted according to what you were interested in. But now with AI that can generate so many things or even fake so many things, this reality is even more extreme. The AI that is trained on models in China inside the wall, with everything—many things got deleted—can construct reality so well that really there are many ways that you can't see what the truth is anymore.

We've already seen so much of that with fake news. It always shocks me when I go back home and see my grandparents scrolling on their phone—every one of those videos is fake, and they don't have the ability to distinguish that. Even though it looks so fake to me, there are just so many more people in the population like that who can't distinguish what is real.

HL: I want to focus in on that. That's a very interesting topic—this idea of an inability to focus on what is real and what we are conscious of, what is fake and so on. In a TED talk, you spoke of a major theme in your work—how technology mediates our perceptions of reality. You created a project called "Nocturnal Fugue: Echo Vision" and pointed out that, quote, "technology is designed to shape our sense of reality by masking itself as the actual experience of the world. As a result, we are becoming unconscious and unaware that it is happening," end quote. This is fascinating. What is it that society is becoming unconscious and unaware of?

JL: Well, going backwards, Marshall McLuhan had the famous quote "the medium is the message." This medium could be glasses that we see through that we wear for so long that we don't know we're seeing through glass. Nowadays—I think at the time I did that TED talk in 2018—a lot of it was algorithms and social media, how they prompt you. Right now it's how AI reconstructs reality these days. The medium is changing as technology is progressing.

When we are so habitual to something, it gets into us little by little by little, and you no longer realize it exists. You're so used to it. You take it for granted. A lot of what art can do is defamiliarize—take us out of that habitualization, make our glass a bit dirty so we can see it.

At that time, the things that were masking us—we see through this world in a very constrained way. It could be the things that we are exposed to, could be the things we like to see and the algorithm just keeps prompting us with what we should see. Sometimes it could be reality that's just masked by our human sensorial experience. Our unique way of seeing the world is so different than how animals see the world.

And now, to the extreme, a lot of these AIs are making fake stuff that even masks what we see even more, and we're not aware of it.

HL: I want to go back here a little bit to some of the activism. There's one particular project that really goes beyond just raising awareness. A lot of times artwork that has activist components raises awareness and kind of ends there. But you've taken things further. You have this incredible empathy for animals, and you ultimately brought attention to and forced action against Yunnan Province's Wild Elephant Valley. Can you talk about what this project achieved, how it incorporated aspects of AR as well as drones, and then the actual legal action?

JL: Some background: the Asian elephant is the number one protected animal in China. There are only about 200 left that are wild, and 20 of them are in this place called the Wild Elephant Valley. They claim they rescue the elephants, but after they rescue them, they don't send them back to nature. They cruelly train them to perform for human entertainment.

I worked with an NGO and lawyers to sue them. It was a pretty long, year-long lawsuit. In China where you can't really vote, one thing that art can do is stir the whole discussion in the public realm and let the pressure of the public urge the government or private entities to take action.

So I created "The Elephant in the Room" and also "Elephant Sound" to stir this discussion. "The Elephant in the Room" was intentionally designed so you can share it very widely and easily. You just scan a QR code and you can see an elephant full of scars. You click on each scar to know what are the patterns that created all the scars and what caused all this. You click on the augmented reality mode to put this life-size elephant in the room against the elephant full of scars, and each time you click on a scar—

During the court hearing in March 2024, we had a drone carry the sound of the elephant's cry on top of the court and play the sound of the elephant crying there. People around the world and also in China shared it widely and it caused a lot of discussion.

The other work is "Elephant Sound," made from this kid's song from a very famous Japanese anime called "Crayon Shin-chan." It's an anime that most people growing up watched and know about. There's this cute five-year-old boy in the anime who swings—draws his penis into an elephant and swings it around and sings, "Elephant, elephant, why is your nose so long? Mom said a long nose is beautiful," something like that.

I changed the lyrics, and the lyrics talk about the cruel training of the elephants. I worked with a contortionist to dance out how all these different poses that they force the elephants to make are similar to us trying so hard and having so much burden on our bodies to do all these contortions. It was a dance that I tried to make intentionally to go viral on TikTok. I had another work before called "Toss Pan Dance," a video that also went viral on the internet and caused a lot of discussion about dodging responsibilities during COVID between governments.

Because of all this lawsuit and public outcry, the Wild Elephant Valley has completely stopped the elephant training and performance. Interestingly enough, they also stopped the training and performance of peacocks. So good for the peacocks as well.

I'm going back in December to check on them because very easily they may stop this year, and then when there's not much going on, not much outcry, they may come back. So every year I need to go back to check on them. It's a long-running project. It's not like one time you finish and it's done—you need to constantly be looking after them.

HL: It's impressive, all these different projects you've done over the years. With your upcoming participation in the Shenzhen Biennale, your work raises sensitive issues for relatively small organizations like Wild Elephant Valley that we've just talked about, as well as the Chinese Communist Party. What concerns do you have about how you will be received or treated back home in China?

JL: That's a good question. That goes back to what I was talking about—how artists need to be smart in a way that you still build up your career, your artistic career, and not get—we call it "drinking tea with the police" all the time. For me, I emphasize the environmental part. China is encouraging and implementing a lot of environmental regulations. Ecological work like things with elephants and with many of my other works with animals—it falls into that bucket of promoting the environment. It doesn't feel like you're so against the government. You have to be smart about how you tell the story.

HL: I want to ask a couple more questions to see if we can bring things full circle here with the numerous different projects you've done over the years. Perhaps we could start with one idea—maybe you translating your own emotional landscape and something you said previously—and then perhaps move to something that's much more specific to your life right now. As I was preparing for this interview, I read where you had said, quote, "When humans are on the edge of extinction due to environmental breakdown, how can we design an elegant extinction? What can we create that the upcoming species—in this case the octopus—will remember us with a little bit of tenderness and empathy?" End quote. Tell me more about that. What does that mean, and how do you perceive the future?

JL: Well, I think we eventually are going to have some sort of end, just like every creature, every being on this planet or outside of this planet. How do we think about the afterlife of not only individual humans but also humans as a species? We've caused so many extinctions of other species. When they leave this world, they just leave with all their knowledge, all their ways of being and looking at the world—it just disappears, and there's no way to bring them back.

If we think about that for humankind, what can we do there? These days I actually criticize this work of mine because here I'm thinking if the next species is octopus, what can they remember us by? Can they think of us with a little bit of tenderness and empathy? But do they need to remember us? Why do we need to be remembered? I feel it becomes again very human-centric, even though it's very much trying to be a non-human-centric work. But it's a way to think of us from a past life perspective.

These days we dig up things from the underground and reinterpret them—a lot of times from our perspective—like the bones, the remains. When it comes to—part of it is imagining what if octopus archaeologists, the ones who study and dig things in the earth—when they find things that humans made, what would they think about us? What is our, quote-unquote, legacy to them? They may interpret it in a very different way than humans. Our legacy is probably a lot of the plastic that can't biodegrade and all this trash in the Pacific garbage patch that octopuses could find. How do they look at them and find clues to think about what humans are, how they look like, how they behave?

Maybe they find two toys together and they think each toy should actually have eight legs because they think from their octopus-centric point of view, not instead of a human-centric point of view. It's to shift how—if you think about humanity backwards in that way—how that could be and what kind of change we can have if you think it that way.

HL: I want to pull everything full circle here and close up with a question that asks you effectively to examine your present and how you're seeing the future amidst incredible change in your life. You have a newborn daughter, and you have noted that her birth has inspired you to do future projects on pregnancy and motherhood. What do you have in mind around this?

JL: Oh, I have like ten projects in my head right now that are going to be shown in a solo exhibition in April in Austin. I could ramble about different thoughts.

Okay, one is "AI Mom." The godfather of AI, Geoffrey Hinton, recently said we are at this point where we're under the threat that AGI is taking over—it's a higher intelligence than humanity. If we think about what a higher intelligence does to a lower intelligence, which has been what humans do to animals, it never ends up in quite a good result. So how can we avoid that impending AGI takeover of humans? Train AI like a mom. Probably the only example he could think of where a higher intelligence is tolerating a lower intelligence is a mom to a baby. Even though they're messy, sometimes stupid, you still love them, you care about them, you change all their diapers.

There are many things I want to criticize about this. If you think about it as a mom, you also take their unconditional love for granted. That's what we've been thinking about nature as Mother Nature, and we've been taking nature for granted and exploiting all that. What does it really mean for AI? I don't know. But I want to make an extreme version of AI mom—how that could be. Maybe the data is trained on me as a mom, a new mom. Maybe I'll put cameras, sensors, microphones around my nursery so these are all capturing from my daily conversations with the baby. How do we add care to AI so AI cares about the things that created them, that can have some love with us?

Another one is "4D Baby." I have a collaboration with Fumiko, a mathematician, as part of a Science Foundation Open Interval program where we have six months of open conversation—artist with scientist. We've been talking about the four-dimensional world, and I learned that Duchamp had an alternative ego which was Rrose Sélavy—he as Rrose as a she. That's the four-dimensional version of him. Because we are in the three-dimensional world, and if we unfold a 4D cube—unfold a cube—it could be inside out. So like unfold a human, unfold a penis, it becomes a vagina. He brought that into his four-dimensional alter ego.

I was pregnant at that time, and I was thinking, what is a four-dimensional unfold of a pregnant body? You unfold it and the baby is outside. That also maps with time, because a lot of time the fourth dimension is time. So the baby is born, is out. I have an optical illusion work installation that will talk about that—you look from afar, the baby is inside; you go closer, the baby is actually outside with the tricks of optical illusion.

Also during pregnancy, there's this thing called Braxton Hicks. It's like fake contractions, and it happens every day, like every 30 minutes during the third trimester. It turns out Hicks is a white male name—a doctor. A lot of the names relating to pregnancy and female body organs are white males. They named them after themselves because they claim they discovered them, but actually there were a lot of midwives who already discovered them but didn't get named after their names, weren't credited.

You have this weird thing where you're going to the bathroom and then Braxton Hicks is here, or you're spending some time with your husband and then Braxton Hicks is here. I looked up his face—typical male face. I just feel like, okay, this guy is always here when I'm doing something. So I want to make a manga or comic book talking about all this—pretty funny but quite sarcastic—about me doing all these things and then this guy is here. Other things like Pap smear, fallopian tubes—many body parts or procedures are named after male guys. I want to make a funny story about this. There's so many more. Hold on, let me bring up my notes.

Oh yeah, I have a collaboration with two scientists. One is a neonatologist, the other is a maternal-fetal medicine doctor. We're having this art-science collaboration about—they've done a lot of interviews with people who donate their baby's brain. Those babies passed away from preterm birth or abortion or different diseases, and they donate to science. Because it's such a sad story, they can't talk to their family and friends—it's hard to talk about it. But through this science research, they feel they're spending more time with where their baby no longer lives.

We are collecting the stories, having interviews with them, and I am creating artwork around these stories. One reference is I had a work called "Unfinished Farewell" during COVID where we documented a lot of people who passed away from COVID, directly or indirectly. What's their story? What are the heavy help-seeking posts they posted on social media before they passed away? There's this space you enter where you can also leave a message. There will be one work there, together with the physical baby brain slices from the science world, which look so sterile and you completely eliminate what's behind these science sample slides. That's another—this is incredible.

HL: You know, from all these different projects you're working on and what you have coming up—you're telling me you're going to be in Japan for a few months, you're going to China for seeing family of course but also the biennale, you've just moved from Austin to Oakland. With all that you're doing with AI in your classroom and even with your artwork, how do you perceive the future? Do you feel overly optimistic, more pessimistic? What would you say? How do you perceive the coming years for humanity?

JL: I think interestingly cautious. I'm excited about all this development, all this progress we're making. It's an exciting time to be alive right now to see all this AI going on. It's also a time that if we don't be cautious about it or make certain important decisions, we could see humanity going in an entirely different route.

Having a newborn, you also get to see from her lens—she's born in a time when AGI is possible. What does it mean for her learning? Learning will be very different. Does it still make sense to learn or memorize a lot of stuff? Maybe not, or maybe certain stuff you really should still learn.

As an artist, I'm excited to be part of being the leading voice in this discussion. Hopefully it could shift something. What excites me the most about artist work with AI is that we think about all these cautions, we think about all the ethical concerns, we find edge cases—think about what are the corner cases of technology and try that out. It's not really the generative part of image-making that interests me, but finding these edge cases of technology is more interesting.

Hugh Leeman: It's exciting to hear what you're up to, and I'm enthusiastic to hear what happens with all that you have coming up here in the coming months, but also your show in April in Austin. This is exciting. Thank you for making time and sharing these ideas. It's beautiful to hear the world through your own voice, through these works that we've looked at, but also to hear how you're thinking about the future. I feel like you're navigating a very unique time for all people, but also very unique for yourself, and it's impressive to see. So thank you.

Jiabao Li: Thank you. These days—I think the past four or five years—I've been working a lot with animals, interspecies co-creation. And now with motherhood and a lot of the female health work, I find it coming full circle, how it's all connected. Essentially it's about how do we foster care among different species, especially from humans to other species, and also probably maybe from AI to humans. Care is directly related to motherhood, like the AI mom I was talking about. I see that coming full circle.