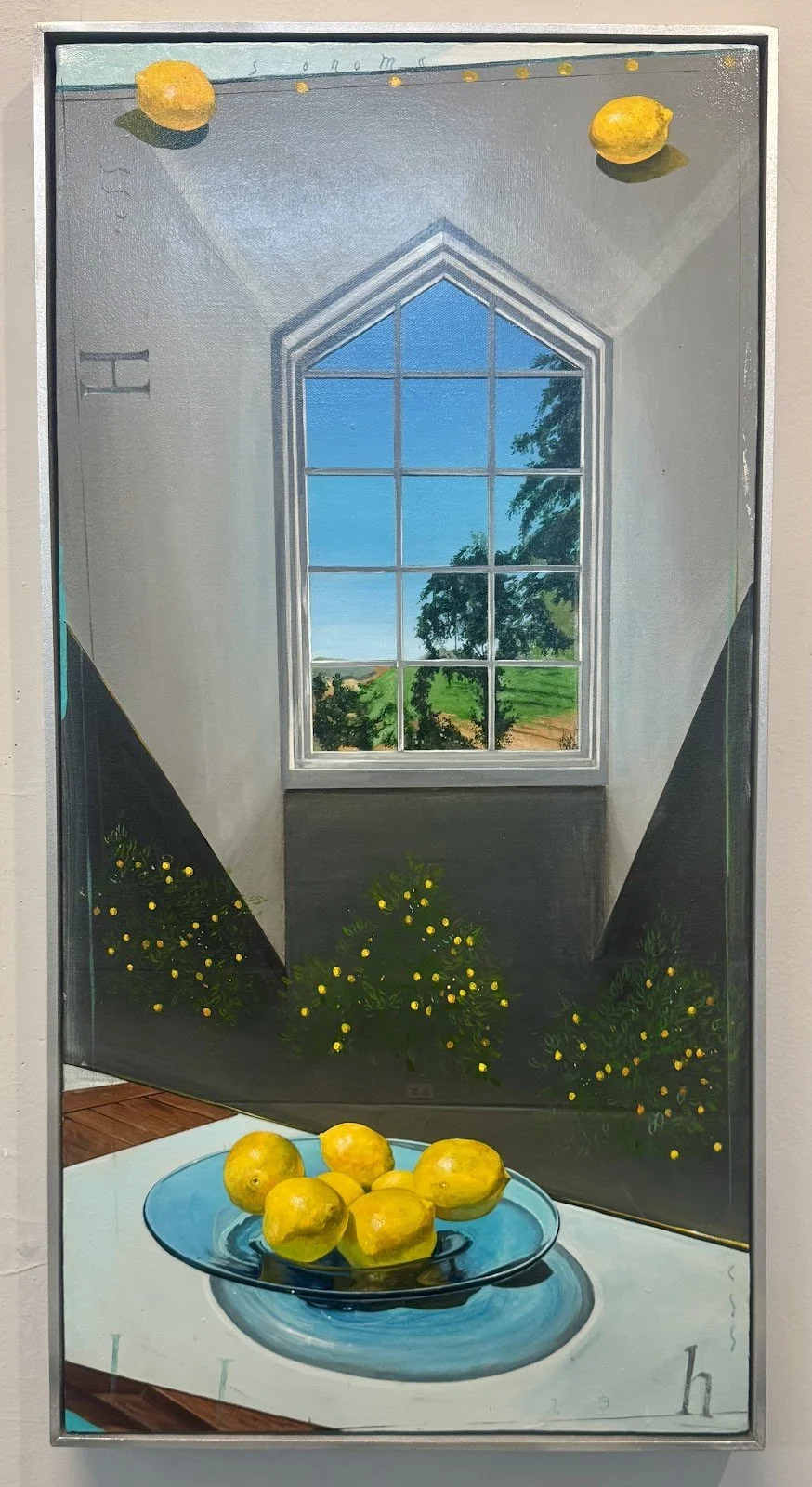

Artist Paul Gibson at Hunters Point Shipyard Open Studios, Fall 2025, San Francisco

By Matt Gonzalez

San Francisco and Sonoma-based artist Paul Gibson, who has maintained a studio at Hunter’s Point since 1991, works primarily within the genre of realism but sometimes adds gestural expressionism and multiple vanishing points to both introduce movement into the finished painting as well as create its distinctive mood. As such, Gibson playfully recasts perspective, making the label of “realist” incongruous. The objects selected are often mundane tools one might find in any American garage. Rakes, shovels, and electrical cords are favorite subjects he reappraises. Their ordinariness belies the socio-economic commentary evident. Rendering a worker tool highlights a relationship with manual labor; the artist is himself a worker. The exchange value the picture will eventually attract, irrefutably, becomes part of the narrative.

Gibson probes other objects as well. The toys he paints trigger a nostalgia for a time he may have lovingly handled such objects. The paintings exemplify how maturity separates us from an earlier and simpler time, raising issues of how societal expectations alienate us from our essential nature. In each case, whether the object is a toy or a worker’s tool, Gibson offers the dichotomy between realism and something vaguer, more emotionally charged. When Gibson paints in an expressionist manner, he invokes Alberto Giacometti’s drawing work, which employed the looseness realist painters usually disavow. He renders spiritual portraits, from live models, where the dark paint and bold moves capture the impassioned qualities he discerns in the sitter. The objective is to represent a person as they are, regardless of strict realism. Gibson chases the essence of things and people.

Despite his departure from strict naturalism, Gibson’s work is best understood in relation to realism, which focuses on rendering closely observed details from everyday life, details that the artist is well aware of because he lives embedded among them. Realism emerged in the mid-19th century as a movement depicting the lives of previously discounted people. Workers in familiar surroundings were suddenly preferred over idealized renderings of classically accepted beauty, thus inviting reflection on social issues. This new painting was a repudiation of Romanticism and Neoclassicism, which favored mythological and historical themes. The resistance to reverence, in favor of the ordinary, can be said to have democratized art. Realism prioritizes the banal or ordinary, thus substituting established notions of beauty in favor of social and political ideas. Realists see beauty in the truth of the object or in rendering working-class life, and they generally prefer it to the sentimentality of classical portrayals of beauty, which have been overly represented throughout the history of art.

Gibson’s affinity to Gustave Courbet, where the treatment of the subject has elements of naturalism combined with a loose brush to convey sentiment and attitude, is evident. Not content to strictly paint what he sees, Gibson’s objects are depicted by utilizing several vanishing points, thereby offering the viewer various perspectives which alter the otherwise stationary subject. He creates a stirring within the still painting via spatial distortion. By doing so, he introduces the importance of movement within the framework of truth. Perceived within an uncontained field and shifting viewpoints, the paintings suddenly offer a wide range of angles signifying possibilities. Add to this, like Courbet, a penchant for a loose brush treatment, seemingly vignettes of abstractions, and Gibson manages to repudiate the choice between figuration and the abstract canvas, opting to render both.

Gibson isn’t alone in seeing the positive effect distortion can have within the genre of realism. As a young painter, during a visit to England, Gibson saw in Paul Cezanne's work a unique application of perspective principles that he appropriated in his own work. Cezanne's blurred landscapes, which have captivated many artists, weren't what caught his attention. It was Cezanne's use of a perspective that blended the horizon line with multiple and competing vanishing points. Gibson started to be able to make his paintings look real and shift in a way he hadn't before. Abandoning the standard proportions within the composition, the human eye isn't limited to a narrow depth of field; Gibson pushes the viewer’s eye to keep every part of the landscape in focus simultaneously. As a result, even a seemingly mundane object, what others might disregard as an accessory, is now capable of captivating the viewer's attention across a wide-ranging field of vision. The foreshortening artists typically use to create the illusion of depth and perception is minimized. Objects don't have to be rendered larger or smaller depending on their distance from the viewer. The subject isn't presented extending into space. Instead, Gibson achieves three-dimensionality with several vanishing points, allowing for a different kind of spatial accuracy.

Gibson applies various methods to push forward his subtly distorted realism. For instance, he'll purposefully leave a shadow out of the picture, seeming a mistake, to draw greater attention to the staged still-life, creating something awkward. The use of reflective light, playing against shadow effects, results in a brighter composition. He uses matte surfaces to keep reflective light to a minimum, further misrepresenting expected proportions. Gibson also uses a limited palette, avoiding undiluted reds and blues. He uses umber colors combined with black and just a touch of white. He prefers deep oranges, utilized with greater amounts of cadmium reds. He will often directly place stencil letters and text into the painting, directly telling the story of the painting. He uses abstraction and mark-making (even scratching) surrounding the main compositional focus to diminish austere realism. He seems to reduce the object to the least brush strokes he can, all the while maintaining its honesty.

Gibson insists that his still lifes are simply depictions of objects that inspire him to explore vertical and perpendicular compositions. Yet there is something about returning to tools workers utilize, rakes and long shears, that denote some kind of commentary on work itself. Painting has often been associated with leisure and the sale of paintings relegated to those who have surplus income. What is said when a collector buys a tool of the worker, one they themselves might rarely handle? Maybe it means nothing more than they are drawn to the artistry exhibited. Or could it be something about the painting object/artifact demonstrating that painting is work? By rendering the tools typical of manual labor, Gibson proclaims he is the means of production.

If one views the artist's craftsmanship in relation to capitalist mass production, Gibson can be viewed as a laborer in the true sense of the word. Just as a factory worker might rebel against wealthy industrialists, Gibson presents the ultimate conceit, that he paints laborer tools and sells them as fine art to persons who rarely handle these instruments. Whether intentional or not, it's a subtle critique of capitalism where the aesthetic object reappropriates currency, not paid to laborers, but to the artist-worker.A collector who perhaps has gained wealth harnessing surplus value, now seeks to own unique cultural property that appeals to their aesthetic, and they do so while also satisfying an association with labor they have escaped from. Mark-making is the most unalienated occupation that exists. It reaches into a primal beginning. It represents the manifestation of human desire, imagination, and expectation.

Karl Marx wrote extensively about the alienation of workers under capitalism. This estrangement from natural relationships, perhaps more egalitarian humanistic ones, results from stratification into social classes. In his Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844, Marx explored how a worker loses their core humanity insofar as they lack freedom. This is exemplified when their labor is appropriated in a mode of production where labor is tied not to what they want to do but rather what they must do to trade for currency that allows them to otherwise subsist. This is seen as a diversion from authentic living and an ultimate betrayal when the worker cannot even own the things they create. The same is true for services rendered. Anything produced with their labor falls into this trap, whether they landscape your lawn or paint your house – the worker cannot determine their own leisure, and neither can they own their production. Profit is made from surplus value, the difference between what it costs someone to have the worker produce something (their wages) and what the product or services can be sold for (the retail value). Gibson restores the workers' humanity by presenting their object, a functional tool of labor, to an exalted form, letting viewers ponder its innate significance. The freedom to choose a subject and the style it will be rendered in (if at all), is free and liberating.

Gibson is of German ancestry, although his family hails from Paraguay, first arriving there at the turn of the 19th and 20th century. Although he started painting around the age of thirteen, it wasn't until he was out of college (having studied Architecture at California Polytechnic State University in San Luis Obispo, and later at the Art Center College of Design in Pasadena where he earned a BFA) and in New York City where he won a full scholarship to study at the National Academy of Design, that he committed himself fully to painting. At the National Academy of Design, Gibson studied realism with Harvey Dennerstein and abstraction with Richard Sollarbeck. The marriage of these two styles is still evident in his work, even the most realistically rendered paintings contain elements consistent with non-objective painting.

Gibson's first show was in New York City at a gallery on Broome Street in Lower Manhattan. He was later included in a number of group shows at Allan Stone's famed Manhattan gallery beginning in the 1990s. In 1989, Gibson and his family relocated to San Francisco, and he began teaching drawing at the Academy of Art University, a position he held for 18 years. In San Francisco, he has shown with galleries including George Krevsky Gallery, Andrea Schwartz Gallery, and Studio Shop Gallery (Burlingame), among many others.

Gibson’s work is poignant for its social and political implications and his harnessing of spatial ambiguity. Though seemingly composed in distorted or inexact ways, Gibson has noted that “no matter how far truth may be stretched, reality and fantasy still combine in reasonably believable ways.” He teaches us that realism is a construct and asks us to accept illusion as a form of truth.