Sylvia Fernández

Sylvia Fernández was born in Lima-Perú where she studied Fine Arts at Escuela Superior de Arte Corriente Alterna, where she graduated in 2002 with/ gold medal. She has lived in Lima, showing her work locally and abroad, participating in several collective and individual exhibitions. Since 2022, she has been based in San Diego, California, where she lives and works.

Fernández’s latest shows, Staging the Future, Center of the Arts Museum, Escondido, SD 2025, Sembrando un Jardin, at Oolong Gallery, Encinitas, SD 2024, Dream Syndication, at La Loma Projects, LA, CA, 2024 Shape Shifting, at Two Rooms, San Diego CA 2023, New Isands, at Tyger Tyger gallery, Asheville NC 2023, Nosune, at Pivo Satelite, Sao Paulo Brasil 2022, curated by Bisagra, Suspendidos, Campo Garzon, Uruguay, 2021, Volvamos solo show curated by Nicolás Gómez Echeverri, Galería del Paseo, Lima, Perú, 2021, Negar el desierto at Museo de Arte Contemporáneo MAC Lima, Perú, 2020, Vamos Desapareciendo, solo project at Salón ACME, Mexico city, 2020 and Conversaciones con Carmen solo show curated by Jorge Villacorta, ICPNA Miraflores, Lima, Perú, 2019

The following are excerpts from Sylvia Fernández’s interview.

Hugh Leeman: Sylvia, you grew up in Peru and studied art in Lima. Who was it that first nurtured your creativity and your artistic curiosity along the way?

Sylvia Fernández: I believe that my starting point when I was really young was my sister. She introduced me to painting, and it was like magic. She wanted to be a painter, and I wanted to be an actress because I was little and I thought I had something there. But in school, really young, like in middle school, Rita, my sister, loved to paint, and she started showing me all these books. I was maybe 10 or even less.

For me, it was like I wanted to be there. I want to belong there. I wanted to discover that parallel world. It's like suddenly I fell in love. But it became more conscious as I grew up and realized that the real world was not enough. That started, really little. I didn't draw that much. I started painting when I was a kid and I loved it, but I became conscious of it when I was 13. I got into a workshop summer class, and I loved it, and I started with a portrait. That was the beginning because through the portrait I could see myself, and it was like I could belong somewhere else. It took me, and then of course I fell in love with surrealism. It was like magic. The impressionists were amazing for color.

Several things made it the perfect combination for me to feel like I wanted to discover this. I want to know more. Then my father—this is a really nice, cute story. My mom took a trip to Europe, and it took like forever for me because I was really close to her, but it took like a month or maybe more. My father said, "Let's paint something together." He loved to paint, and he was really crafty. He said, "Let's start something together," and we started painting an image of the end of a car race. He's in love with cars. He proposed the image.

We started painting, and I was like, "When are we going to finish?" And he said, "When we finish the painting, your mom's going to come back." For me, it was like, okay, I always painted, feeling that when this was done, something was going to happen. And it did. We finished the painting, and my mom came at night. So it was like magic. I believe that relation with painting, that kind of time or interest in another dimension, started there without even noticing. I remember that—something can happen if you paint something, just like a wish or something magic.

Mother, 15 x 20 inches, oil on paper, 2025

HL: You mentioned your sister, and then this connection that's very beautiful with your mother and your father with the painting. Your grandmother appears in a painting, and it's the first in a series of all pink paintings, and you've shared stories about her life and her connection with your grandfather. What is her role in your art?

SF: My grandma, my mom's mother, was always present for me. She was always there. She was like home. She was the meaning of family, along with my closest family: my mom, my dad, and my sister. But Grandma was this big, established woman. Even though she didn't do much, I admired her just for being herself.

She played the drums when she was 15. She wanted to be a rocker but couldn't. She was an excellent pianist. She danced. She did all these things but never evolved in them. She had this strong character, and the way she saw life was her way, whether you agreed or not.

Toward the end of her life, we started talking more and grew closer. I did a whole show called "Conversaciones con Carmen"—Conversations with Carmen. She never appeared in any canvas as a figure, but I did one painting that was the tones of her skin. I sat with her, took her hand, and translated all her freckles, everything, into my palette. I did one huge canvas, big enough to make me feel like you're all over. Then a year later, she died.

So I created this huge series where the main core was this constant conversation about living, about dying—not because she talked about death, but because she spoke in a way that showed she was finishing her life. "This is almost the end" or "I did this" or "I wish I could do this." These things came up in our conversations. What was really interesting is that she never felt scared. She never wondered what comes after or what it would be like. She had this feeling of "I want to go." That's what I explored in that series, even though she's not there, and all the pieces are really different.

That also happens to me, I don't have a style. Sometimes I'm much more realistic, sometimes much more abstract. It depends on, it's like not every day is the same. Sometimes you feel totally abstracted and your mind is scattered, and sometimes everything is sharp. That's how I relate to painting, too. For a while it was a struggle because I'd think, where am I? I'm so deep in it, then suddenly I'm on the surface. Sometimes I get so deep I find different things. I've learned to respect that, and now I even like it because I realize it's my pulse, my rhythm, my life. It's there.

HL: In the pandemic during the quarantine you said to yourself, if I cannot go out I have to go in. During such a dark and challenging time, what was that inner journey like?

SF: Being really selfish because the context was so hard. It was amazing because I discovered so many levels inside me through painting. I gathered everything—you're living in the same place you're painting, you're cooking, my kids were there, everything was totally tangled. I started weaving with everything and going inside, thinking, okay, I'm going to see how deep I can get, how much I can rescue from really down deep.

Something shifted then as a painter. It's not that I haven't been that deep before, but this was constant. I could come in and come out, come in and come out of this state that I really loved. It was dark, but it was light too in a good way. It was totally nourishing because I realized how vulnerable I was—how vulnerable I am in that state. It got really interesting, and I think COVID was where I started becoming who I am now as a painter, because I was looking for something deeper, a place or a state.

It was really interesting how I started, and even in my painting—the way I began to paint physically, the way I started to manage color, the way I created this first coat just waiting for something afterwards to happen. Even the relationship with painting started to change.

HL: You said something really interesting here, the idea of discovering the self through painting. Previously, you've said that you believe the dark places let you see the light. This seems to really connect both of those. What is it that the darkness has allowed you to see light in life?

SF: I believe it's a place we must visit and allow ourselves to explore, because for me it's not a scary place at all. There are situations in life that put you in fear mode and push you into a darkness where you don't want to be. In my case, I've gotten in because I want to.

When I was really young and started to paint in art school, I remember the first year I started having panic attacks. They were connected to a disease I have called Malta fever, which is really weird. I had to have treatment for six months. It's from eating unpasteurized milk and cheese. I went up to the Andes and was there for almost two months, and I went to the market and ate cheese every day with my juice. When I came back, this started happening, and I got depressed because of the disease itself. It breaks your nervous system—vitamin B goes way down.

Instead of just going out, I did everything I could medically with medicines and everything the way you should. But I also started therapy because I was interested in what I was feeling, and I wanted to know more. Then I started relating my painting and my career—what I was doing—to something bigger. It wasn't just painting because I was good at it or because it was an extension of myself. It was in me. I believe that when I was really young, I started to understand that I could feel even better and take painting as a cure. It really related down deep to me. It wasn't just about art—it transformed in that way.

I started art school like that, respecting my own process and putting it out there, being totally honest, being present. It was always related to what I was feeling. Darkness was part of it. Getting in was part of it—not just "oh, this is a pretty painting." I didn't care that much about that. That's how it started.

Even though I got pregnant in the last year of art school. I was 21, so I was really young, but I decided of course to keep it, and he was going to be part of it. I was in my final year project, and I remember my project was already set. I was going to present to the mentors, to my teachers, and I said, "I have to stop and figure it out because I'm not going to be able to do this. I don't feel it anymore, and I want to respect that."

They were like, "You don't have to feel it. You just have to do it. It's separate. You're pregnant right now and you feel how you feel, but your work is your work."

And I was like, "No, this is one. I've been conscious, and it's been totally related to me, so darkness and light, everyday life—it has to be there in the art."

HL: Earlier you mentioned that you were looking for something deeper and even before that when we started this conversation you mentioned that life wasn't enough and that's what turned you on to painting. In regards to your recent show you said, "While I was painting these landscapes without any reference I was looking for a lost place in my memory, a place I didn't quite remember but knew it felt like an illusion right away." Tell me about this idea of the lost place that you're looking for in your memory. What is it?

SF: I believe that everybody, we all belong here and we all relate as humans. We're all in it together, and we share what we see and what we feel. But I believe that each one of us has our own place where we belong. Not like you're an alien and you belong to some other planet. I believe that down deep, and it's totally related to a spiritual state, not a physical state.

Those kinds of moments when I get into painting—when I start to paint, it's like I meditate too. In a way it's the same. You start painting and you're not in it, and suddenly you're in it and you lose yourself. You're not there anymore. I believe that ego disappears and you're there, in your place. Sometimes it keeps changing because it's not the same kind of image that I can see—maybe I can't even repeat it—but I can feel the same space where I belong. So it feels like home.

When I find these places or these landscapes, it's like I belong here. I want to know more. I'm interested. You're creating it because you're painting it, but at the same time the painting is giving you so much back, and there you are in it, allowing everything to happen.

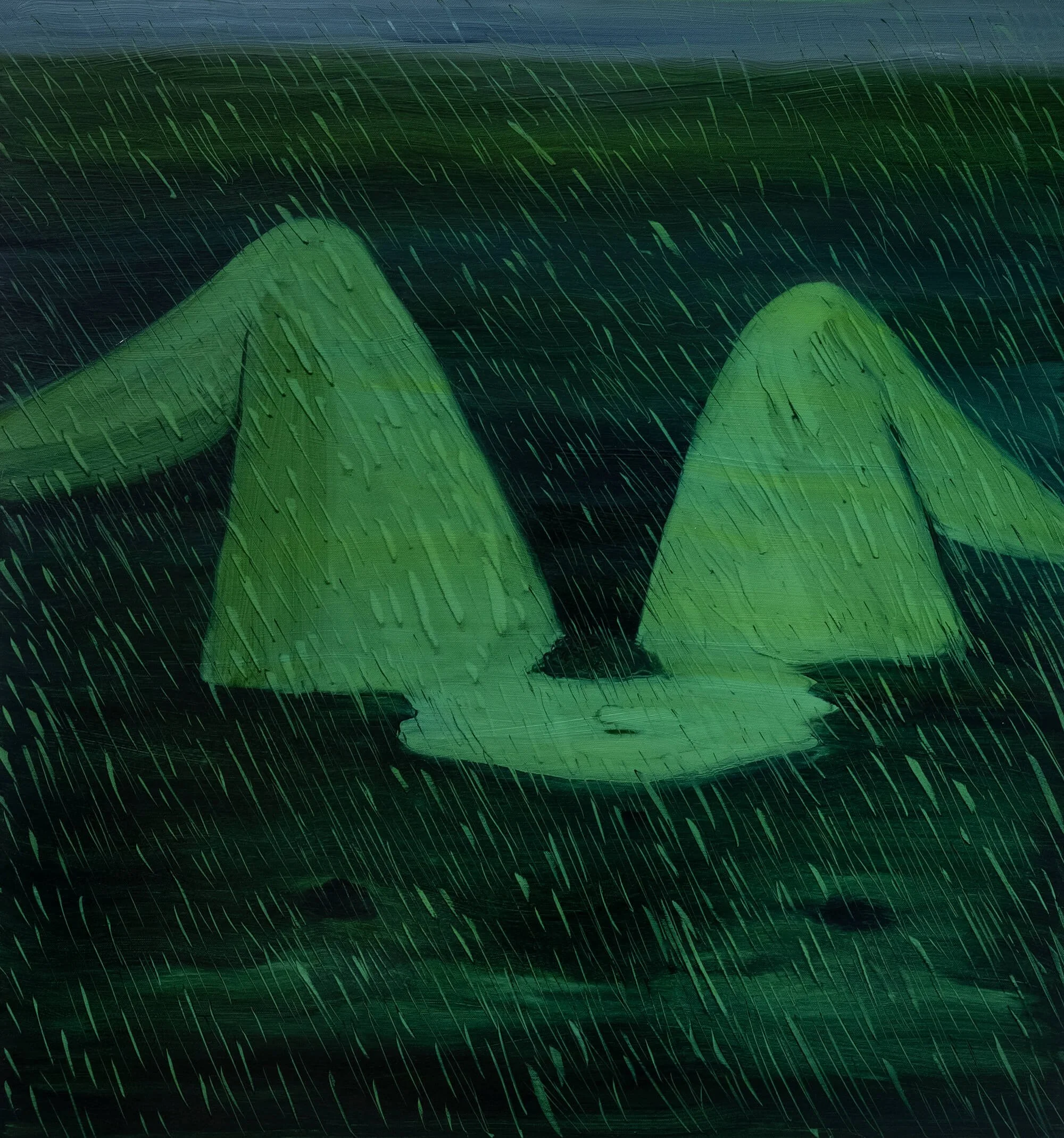

In the case of The Illusion of Paradise, it's a series I'm still working on. The last show started that way, and what was really interesting is that when I finished that landscape, I started looking at it thinking, Where is this? I paint in a day so at night I can see it, and I thought, it's so weird. I don't even feel—because I was already out—and I thought, where am I or what am I trying? I couldn't go to sleep, and then I realized the next day that my shadow through the window was on top of it. And I said, "That's it."

So I started tracing out just my silhouette as a line, and I found light because the first coat is a light color. And it was like, now this place—not even that I belong to the place, it's like we belong. And it felt so good. My shadow and my silhouette turned this little paradise into an illusion. And in Spanish, "ilusión" also means something that doesn't exist, but there's also hope in ilusión because it's something that's going to happen. So it's exactly like my father, just thinking about what I've just said—like when we finish this, something is going to happen.

That state, that constant surprise with painting—that's what thrills me. That's what I'm really drawn to, more than "oh, I'm going to do a plant." It's not about the plant.

HL: You mentioned this idea of a spiritual state and that it's a spiritual experience in many ways. You've previously talked about internal landscapes and an inner paradise and then paintings that connect human bodies to the natural world. Beyond this, there's this recurring theme of plants and flora in your work. What does the internal landscape look like to you and how do you access it?

SF: I believe that place has to do with my memory. It's like whenever you have an archive in your mind, in your brain, and it's related to what you've lived and what you think you've seen or felt—because sometimes memory reshapes everything and it's not even the real memory. I believe in that place, that's what happens.

I have tons of flora and fauna. I discovered a long time ago my grandfather is from the jungle. When he was dying, no one in my family knew the jungle. We were from Lima, the center city and everything. My grandfather said to me—I was maybe 15—he said, "You should go to the jungle. You would love it. I know you would." Because nobody here wanted to connect to that part.

I said, "Okay." I took a trip when he died, and I went. When the door of the airplane opened—because it's so rural that it's not connected with a tube or anything, it just opened—the smell and what I felt, it was like, this is it. My paintings have to do with that kind of feeling, feelings of connection where you realize this is the place and it takes you somewhere else. So all the senses are involved, but also all these kinds of memories.

Since I'm here—I moved to California almost four years ago, it's going to be in February—when I came here, I started to connect with nature right away, more than anything else, because you're new. You don't know anybody that much. I have friends, but how do you connect to a place? So nature has been like a bridge to connection all this time.

What's amazing is that we share the same geographical environment as Lima, Peru, because it's a desert close to the ocean. When we moved, we decided to come really close to the ocean because it's the same ocean—it's the Pacific Ocean. So I thought, I want to feel at home. I want to see my ocean at least, to feel in my place. So we moved two blocks away from the ocean. Then we realized it was really expensive and we're still coming back, but I'm not so far away from it.

That's how it started. I started this series called "New Islands," and it was about the body just surrendering to the water. It was like, okay, I'm here now. I have to be part of it. I'm an island because I'm by myself, but I want to belong in a way. It's not belonging as identity—it's deeper, as you say. It's in another state, another level.

And I started recognizing plants, the same plants. How do they grow here? They grow even more. They bloom in another way. They have flowers. Back home, they don't. So all these things started attracting me. And of course here it's much more wild than back home. I mean, you can see foxes or coyotes or birds that you don't see back there. The city is much more gloomy and dirty. I'm in Oceanside, so it's a really pretty town near the beach. I have more access to that feeling of nature, really close by.

That's how it started—restarted here—because back home it started with "Conversaciones con Carmen." That's my first connection with nature, with my dog, with his hair, with animals. It has always been present, but it was more conscious. And now it has become not a theme, but a symbolic way and a poetic way to talk about it.

HL: I want to connect with this idea of moving. There's a story you tell: in Lima, you put your house up for sale and almost immediately it sells, and you take that as a sign, and that then leads to your move from Lima thousands of miles north to San Diego. Tell me about that experience and how did you take that as a sign and where does that all come from? Where are the signs coming from?

SF: I am really intuitive. I belong more to my intuition than my thoughts. I mean, whenever I think too much—it's not that I don't think, I do think and I think a lot—but I trust my intuition more because you feel right, because it feels good. It's really weird because sometimes I look—I'm 47, I should be thinking in another way or planning. But I've lived my life like this always. So for me it wasn't like "I am totally nuts, I'm going to go because this is a sign." I've lived like this always.

When I got pregnant and I was 21, my partner and I decided—okay, he was living in Spain. He came back. It took a while to make things real because he didn't have a place. I lived with my parents. It was totally messy. But when I realized I was pregnant, for me it wasn't even a question of thinking. It felt so good. And if you had to think about it, it was a no. Of course I was so young. But I said no, it's a total yes, because I knew he was a he—so it was really weird. But it was like, totally, he's going to be part of it. When he came, he was an old soul. And then I realized, how could I have not even thought of not having him. Every decision I've made in my life has been like that.

So for me, that's how I am, and my partner kind of too. So we're dreamers. And it has never gone wrong. I mean, it's tough. It's difficult because suddenly you realize it's going to be much more difficult than you thought. But then you make it happen. You make it work. It's part of you. It's your life. So it's like, okay, this is messy or whatever, you have problems—okay, what's the best we can do? And then you continue. So for me, I'm not a dramatic person or a victim of whatever happens. It's more like you bring life to things in a way. So that's your job, my mission. That's that.

So when we sold the house, we thought it was going to take longer, like six months. We'd already left Lucas, my oldest son, in Pasadena because he was starting music college. Jason is American, so we were thinking, let's give it a try. I've never been attracted to America that much because I was more attracted to going to Europe. Jason was already there when we began, but then we stayed in Lima forever and it was good. It was going fine until Lucas decided to come. A door opened. Something happened and we said, what if we try?

Okay, the only way was selling the house because there were no savings or anything, and we thought it's going to take six months at least. It took a month. It took a month. So it was too fast. We had to make our suitcases and leave. I started giving away all my things, then put a few in storage, and then we said let's go. And then here was a state of a trip for six months where you're like, you're not even here but you're here, and then boom, it was like, okay, I'm living here. I have to make it work.

But wherever I can paint, that's another thing—I'm going to be okay, I think. My studio was really tiny and I started painting really little on paper, and it's like rewinding everything. Sometimes I closed my eyes and I saw my studio back home and thought, what have I done? But then things change. Yeah.

HL: I love this idea of wherever I can paint I'm going to be fine. And it connects with this idea I've come across of you saying previously that you've called painting a constant dialogue, which implies that it's not just you making the painting, but the painting is making you in some ways. What does that conversation sound like between you and the painting? And when it talks back to you, what is it telling you or teaching you?

SF: It has turned now—it has always been a conversation, even when I was in art school, because you're giving something, there's going to be a result, and suddenly it starts. I believe the conversation starts when you're not getting what you want. You start mixing colors and you don't know how to do them, or you don't even know how to get there, and you start failing in a way. You're painting this bottle, imagine, and you have to be so accurate, training your eye, and then suddenly your shadow is more blue than black or whatever. And then that starts—okay, I'm doing this but it's not working, and you struggle because that's how you start. You struggle because you don't know how to.

But in that gap of struggling, the conversation starts, because suddenly something happens that you weren't imagining or weren't even thinking. And then it's like, oh—so a little door opens. Okay, you're not doing it as your teacher says or as you should, or because you're in a class where you should do whatever they're teaching. You don't have the freedom yet when you start. In that exercise of trying to make it, you realize there's something here. This is giving me back something.

At the beginning, yes, you want to see what you want to see or you want to go where you want to go, and that's you in control. But what's really amazing is when you are not in control and real things start to happen, because when you know what you're doing, for me you're not there. You should get to a point where you don't know where you are to understand whatever you want to understand, and it gets more interesting because you ask, where am I going? Where am I standing? And those questions are the ones that really open and connect you to whatever you want to be connected with.

I believe that conversation has changed. It's like someone you meet for the first time and then it's your companion. So afterwards, how do you still have the same conversation? You don't have the same conversation. You're evolving in the conversation. So now it's a pleasure.

I believe that when I was really young, I struggled. Sometimes you'd get mad at the painting, at the surface, at your canvas, at the palette. You'd go out, have a smoke or whatever. You'd have all this drama about it, and then you'd come back and the painting was still the same. And then you'd realize, okay, he's teaching me to calm down, to get in another mood, to understand. So understanding has changed in that way, and the conversation has changed too.

It's really interesting because when I start, I just have to have the surface, the texture of the surface that I really want, and that's it. Then it starts. If the canvas isn't prepared, I don't go into a blank canvas right away. I go into a canvas that has a first coat of oil. So for me, it's like I start to dance and you can come back and forth, back and forth, and something happens there. But if I have to struggle with a white canvas and the absorption of the oil and the medium and everything, I'm out there. I'm not in it. I stay on the surface. I never get in.

It's not about getting to an image that you have. I'm not painting purple because it's purple. It's a different kind of relation. I give, it gives back. I have to stop, look. It's different.

HL: I want to bring things full circle here with one more question that connects this throughline that you've talked about in many ways of being intuitive or instinctual in so much of your practice. Earlier in our conversation you mentioned that you've always been very intuitive and I've seen where you've mentioned the importance of instinct, something you really value. What are your instincts and your intuitions telling you about where you are now in life and where you want to go with your art?

SF: It's about expansion in a way. I'm 47, but I'm like a child at the same time too. I have this wanting more and getting surprised and feeling—so I feel good where I am. It feels good.

At the beginning here—what's really interesting now that you're asking me—it's like I've never been so conscious about my career itself, because it started hard with a kid growing up. It wasn't that I had to put myself aside to bring him up in a way, but it also made me evolve in another way. So I've shared my space. The thing is that it feels good where I am right now, and it feels like it's going to expand. It's going to grow. I'm connecting with the viewer in another way.

Now, for a while, I'm more interested in connecting with the viewer and sharing the journey. And being honest enough to make the other one get in, rather than achieving. It's more about the inner world that the practice gives you and the painting allows you, than my career. I think that the result of your work is the career part.

I came here, I never knew anybody, and I didn't even think about this place like, oh, this is an excellent place to be an artist. Not at all. I thought, it's going to be near Lucas, my son. I don't want to live in LA. I know LA is a cultural bomb, but I don't want to live in LA. San Francisco was like, we want to go too, but it was too chilly. We want to stay close to the ocean. Let's stay here.

Then I started looking around and I said, okay, this is going to be tough because I'm not connected. Now I'm more connected, but at the beginning I wasn't. So I started to paint and just my Instagram was out there, and that was really interesting because nobody knew me, but my work spoke for itself. So that connected me. That's how it started here, and so far so good.

I cannot say that I want more or less. I'm happy with what's going on. So my intuition and my instincts—I feel good. I feel good where I am. I think I've achieved something, and little by little I'm walking there and I like the place. Not the place itself, but I like the place that I am in right now. So if you take me to China, I think it's going to take three months and then I'm going to be myself again. If I can paint, I'm going to be okay. And connections nowadays, you have to make them happen and it is hard, but they come along.

Hugh Leeman: Sylvia Fernández, thank you so much. In listening to you, one of the things I think about is there's an author I really like, David Mitchell, and he wrote in one of his books that '“the soul is a verb, not a noun.” And I feel like this very much so describes some of this instinctual and intuitive process that you're talking about. So thank you for sharing what you're sharing and thank you for your creativity.

Sylvia Fernández: Thank you. Thank you for having me, for wanting to know more, and being interested in what I do.