Human / Nature: California Zen in Big Sur and the Bay Area, Monterey Museum of Art

September 18, 2025 - January 25, 2026

By Scott Snibbe

Does staring at a blank wall for a thousand hours sound easy or relaxing? Does it sound particularly “zen” in the flavorless way we now use this word to brand a nail spa or tea blend? Yet this aggravating activity sits at the heart of Zen Buddhism as it took root in California’s counterculture of the 1950s and ’60s, flowing through the open minds of writers and artists drawn to the creative poles of San Francisco and Big Sur.

Human / Nature: California Zen in Big Sur and the Bay Area is a breathtaking show now on view at the Monterey Museum of Art that illuminates the influence of Zen on artists of this transformative time. Though most of its works are more than half a century old, they feel freshly made and uncannily relevant today.

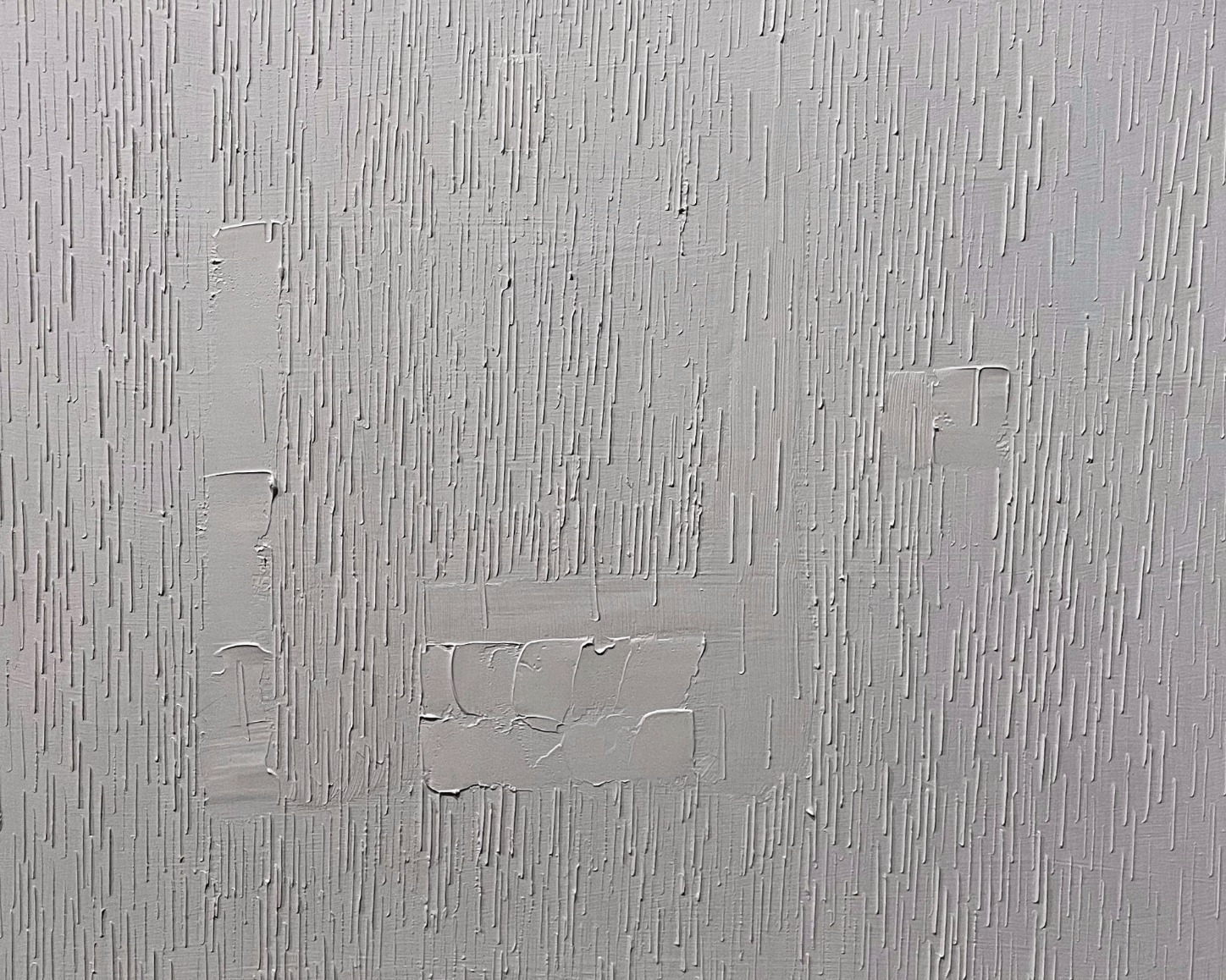

Lee Mullican’s aptly titled Untitled (1958) called to me as I stepped into the intimate gallery: a pure white painting that, as you approach, reveals a surface strewn with textured streaks and planes, like a petrified rainstorm. I couldn’t help thinking of Zen’s core practice, because few objects I’ve ever seen better materialize the outcome of staring interminably at a white wall. An untitleable white expanse that at first seems flat, and then anything but, reveals itself as the painter’s reckoning with the tyranny of the blank rectangle.

John Baxter’s adjacent 1950s work—again, Untitled—sets two found stones beside one another on a sea-softened wood base. I yearned to touch their voluptuous, mottled surfaces that lean into one another like well-paired dancers. But the piece’s owners prize it so dearly they’ve encased it behind bulletproof glass to protect it from sensualists like me.

Shizen—naturalness—is a guiding principle in Zen-inspired art, a straightforward label for a work made of beach-found objects. But this show reminds us that even as we stand in a city apartment staring at a painting on a wall (or making one), we remain part of nature. “Devoid of anything artificial or strained” is a more precise definition of shizen, one that reminds us we can turn our minds back toward a natural state.

When we touch this deeper part of our mind, whether by relaxing on the beach or engaging in a staring contest with a wall, we come closer to the nature we ourselves embody. Buddhists call this subtler nature of mind—glimpsed when the mind looks at itself—Buddha nature. The show’s curator calls it “calm excitement.”

Yet struggle—rather than calm—may be the better way to describe the practice of Zen that (eventually) leads to a calmer mind. And struggle is visible in these works. Oakland artist Arthur Monroe’s exploding abstract-expressionist painting (you guessed it, Untitled) embodies the attention, spontaneity, and curiosity that Zen practice requires. Openness may be an even better word for the mind capable of creating such a masterpiece—an openness that accepts the inevitable failures as the human mind grapples with body, tools, materials, and itself.

I returned several times to this small painting, getting to know it better, seeing it differently each time. The broad cadmium and ochre expanses flanking its sides feel like the portal of a Big Sur cave—one unable to contain the raised strokes splashing through in lush ultramarine, umber, and moss.

For a moment, I wanted to call these paintings Zen abstract expressionism, but you might as well label every abstract expressionist painting that way, because all successful ones embody the process of wrestling with the unrepeatable, fundamentally unrepresentable present moment.

Claire Falkenstein’s Plate IX (1963) breaks the streak of Untitleds, but holds to a theme of relief: media that lift off a canvas’ surface, refusing the plane’s constraint. Like many “Zen” artists, her strongest influence was less Zen practice itself than a lifetime spent in nature: from the beaches and forests of her Oregon youth to the tree-covered California campuses of Mills College and UC Berkeley.

In Plate IX, she scatters intersecting twigs beneath wood-rubbed paper, entangling them with curlicue scratches. Her mind uses one form of nature (twigs) to simulate the invisible rules underlying another (cracked clay), creating a riddle made from nature about itself.

In the same vein, Richard Faralla’s Lozenge II (1960) regathers driftwood scraps onto a diamond-shaped canvas—all painted matte black. The effect is a window into an ocean of wood, the midnight scales of a deepwater fish, or the sealed mouth of a sacred cave.

Nancy Genn’s Tidelines is curiously named after the ocean—a tangle of steel without a center that hints at the ultimate nature of everything (as Buddhism describes it): emptiness. “Form is emptiness, emptiness is form” is one of the most famous phrases from one of the most famous Buddhist texts, the Heart Sutra. Recited daily by monks, it reveals in secret language how nothing possesses a fixed center and yet still exists. Another term for emptiness is dependent arising, a way of being far more dynamic and true than the solid, lonely, separate way we often feel.

A common way Buddhists learn the logic of emptiness is through a formula of three ingredients: mind, parts, and causes. Things exist only as a collection of parts that come together through innumerable causes, and become distinct things only when a mind labels them so.

Thus, Genn names her tangle of steel Tidelines, and we call it that. The fact that her sculpture bears little resemblance to an ocean reminds us that the labels we place on things are arbitrary and provisional. “Tree,” “stone,” “paintbrush,” “canvas” are merely sounds we long ago attached to trillions of collected parts gathered through countless causes—just like these works of art, just like us.

But don’t confuse emptiness with existential nihilism, Zen’s European rival for the hearts and minds of postwar counterculture. Things exist—just in a far more dynamic, interdependent way than they ordinarily appear.

Peter Voulkos’ earthenware sculptures embody emptiness too, as a stretching of the mind to encompass the full arc of time and potentiality held in objects. We return to Untitled, here in the form of a grand plate formed from riverbed mud—pockmarked with rough holes, stripped of its function and even its name. This piece begs us to ask, “What is a platter?” just as the curator teases us with a second ceramic piece by JB Blunk beside it (Platter) that stretches the notion of dinnerware even further: a mammoth, stubby, fired-clay starfish whose curled arms and scorched body can’t hold a meal but readily prompts us to question the ultimate nature of reality.

We tend to see abstraction as a modern innovation, but a millennia-old work of art I stumbled upon while wandering the museum’s other galleries suggests otherwise. It made me wonder whether abstraction—perhaps even abstract expressionism—might be among our earliest forms of creative expression.

An adjacent exhibition on mid-century Central Coast artists includes a small Louis Stanislas Slevin photograph, Hands (1920), that stopped me in my tracks. In this beautiful black-and-white image, borrowed from Monterey’s Free Library collection, Slevin captures a cluster of passionately rendered hands on a hidden cave wall created by the Esselen people—long before the Renaissance, the Middle Ages, or even the Greeks created their seminal works of art.

The caption for this photograph echoes common modern interpretations of cave paintings: that they are unknowable or simply “art for art’s sake.” But could this really be why human beings started making art? And why, across continents and millennia, do our earliest images so closely resemble one another?

More recent interpretations tell a different story. As David Lewis-Williams argues in his groundbreaking book The Mind in the Cave, these images are not attempts to depict reality, nor marks of individual self-expression. Instead, they record the shared experience of altered states of consciousness; visions evoked while sitting quietly in the dark of a cave, staring at a wall.

By comparing Paleolithic imagery with more modern shamanistic practices of indigenous peoples, Lewis-Williams identified a striking universality: cave-painted walls as membranes through which hallucinatory visions emerge. Worldwide, over a span of 50,000 years, hands have been stenciled and painted on undulating stone not to represent hands, but more like instructions: dance step patterns that say press here for an altered state of consciousness.

Often overlaid on these hands are abstract forms—dots, lines, squiggles—that have long puzzled scholars. But we now understand them better too: they depict the abstractions produced when the mind looks at itself. Our culture today calls this entoptic imagery—neurological phenomena that arise when sensory input is reduced or deprived. The shamanistic cultures through which all our ancestors passed understood these abstractions as messages from invisible realms, accessible—for those patient enough—through meditations on dim cave walls. To preserve (and provoke) this experience, marks were made on the wall that conveyed the visions that appeared and how to evoke them again.

It is tempting to see the universality of cave art’s ancient abstractions of inner experience as evidence that abstract art is not modern and new, but old and universal. Just as song predates speech, could abstract expression be more primal than representation—a vision of the mind watching itself? And is it possible that the mid-century works of experiential artists wrestling with paint, driftwood, and clay convey what one might have seen millennia ago while sitting silently in a cave—staring at a wall long enough for something profound to appear?