Lee Upton and Jim Toia, The Never Lost Forest, Hunterdon Art Museum

Hunterdon Art Museum, 7 Lower Center Street, Clinton, NJ September 19, 2025– January 11, 2026

By Elizabeth Johnson

For their collaboration at Hunterdon Art Museum, poet Lee Upton supplies words and sculptor Jim Toia sources found woodland materials. The show takes me back to childhood rambles through the forest at dusk, and the unique mixture of security and danger that only wandering amidst endless stands of trees can inspire. Seen together, Upton's poems and Toia's weathered, textured, carefully selected objects suggest the lack of visible boundaries and the nearly overwhelming sense of limitless space that most hikers experience even in semi-rural places, if they venture a mile or two beyond dwellings, outbuildings, billboards, and fences. I am struck by how Upton's poetic plain speaking dovetails with Toia's trust in his objects and materials.

In an email, Upton noted, "The title of the exhibit references the significance of forests and the complex webs of growth within forests. I even like the way that the title almost sounds like something from an enchanted fairy tale—and I do think that forests, when we’re inside them, may make us lose our bearings and experience something very close to enchantment. At the same time, the title suggests art and imagination as continual resources, never to be lost, and the enduring act of mourning, in which memories of those we lost are grafted to our lives."

"From the Trees," which is the title of Upton’s poem and of the installation, summarizes all we need to know while looking. Presenting loosely patterned lines of sycamore leaves, where each is punctured with one laser-cut word, From the Trees suggests infinite combinations of brevity, as leaf and word are stenciled and rendered using ash tree ash, graphite, and charcoal, and appear as cast shadows on the wall. "Reading" the wall is a pleasant, jumbled experience that holds my attention on each separate, simple, declarative utterance, as if the trees have taken over human narrative, and growing one word per leaf per year is more than satisfactory to them. The piece connects writing with seasonal abundance and invites me not only to read slower but to imagine falling leaves telling a story or writing a poem. Ubiquitous, renewable and mostly equal in size and importance, the perforated leaves and their cast shadows elicit a riddle of thought without centralized thinking.

One-line poem fragments etched onto The Forest Sways and Breaks in Waves and cut into The Body Hive come from the poem "Underworlders" from Upton's book The Day Everyday Is. Recalling generic images of mountains, tossing tree branches and crashing ocean waves, The Forest Sways and Breaks in Waves elicits comparative morphology of geology and evolution as a compact, birch bark fragment using old-fashioned script. About the etching process Toia says, "Lafayette College has a laser cutter/etcher in the Art Department's tech lab. I employed a senior art major and Creative and Performing Arts scholar, Duncan White, to help me create these pieces. His skills were essential to the process and success of the show. And since neither of us had worked with tree bark or wasp nest paper––or sycamore leaves, for that matter––it was quite a learning curve and, luckily, a successful one."

The Body Hive presents the poem fragment "Where is the hive that is meant for all our bodies" in blockier, laser-cut script that voids the bellies of the letters "a," "b," "o," "e," and “d," unspooling clockwise around the fragile surface of a flattened paper wasp's nest. Toia says, "Paper wasps abandon their nests after each fall season as the first frost comes. They do not return to them. No treatments are used except time and pressure to flatten forms, [though] one may use water and an atomizer to soften materials before flattening."

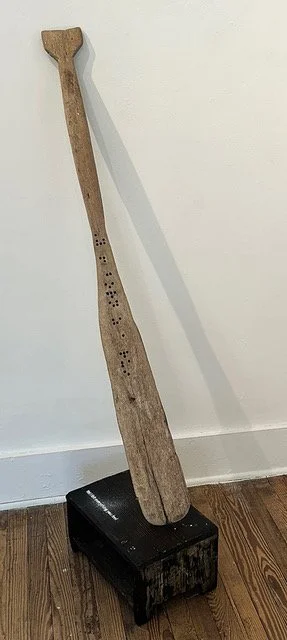

Born as a Ruin presents a powerful conversation between human and natural worlds. A weathered paddle that Toia imbedded with black plastic beads spelling in braille Upton's one-line poem "You were born as a ruin" is propped on a black bench. Black ashes were sieved through a template onto a pile of white chalk on the bench to answer: "Yet I felt everything you feel." The piece alludes to feeling words instead of reading them, humanity's blindness, and the hopeful poetics of communing with nature. The past tense is key, lending an after-death sensibility to shared existence, and sustaining the chorus of two contrasting voices. It's a haunting piece.

When talking about how Born as a Ruin developed, Toia says, "The paddle, which I can only surmise was homemade, was found floating in a Florida Keys canal. I was struck by its aged resemblance to a whale. It has been sitting on my wall for years, waiting to be used. An old sage of sorts with a demanding presence. When I read Lee’s one line poem “You were born as a ruin” I immediately thought of the paddle. I then asked Lee if it would be okay to couple [it with] another of her one-line poems “I felt everything you feel” and add “Yet” to that phrase, making the piece a call and response using a small bench as a landing spot for both that phrase and the oar. She agreed to the addition immediately. For me the phrase “You were born as a ruin” took on a suggestive reading when seeing the oar as a whale. The reference to a beleaguered and abused species became pronounced while leaving room for other interpretations."

People are Camouflage is the most painting-like piece in the exhibit and the most critical of humankind. Toia worked in ink and gouache to both enhance and obscure the words on a graphite rubbing of a palm tree on mulberry paper. "The words disappeared,” he says, “and I had to salvage them often, rescuing them multiple times throughout the process." People are Camouflage suggests the shallowness of humans’ self-knowledge, self-confidence, authority.

Upton recalls, "When I wrote those words, I was attempting to do the impossible—to think in terms of how a tree might conceptualize humans. My first draft was something on the order of 'To your politicians, you are camouflage.' Our politicians may hide behind us, or what they assume about us. I shortened the line later when I thought more about how we create camouflage fabric to blend into our environment, to appear undifferentiated from our surroundings. Perhaps to a tree we blend in, seem no more important than any other living being. Perhaps we are camouflage—perhaps we are continually hiding ourselves in one way or another for various purposes."

The Never Lost Forest supports innate sympathy with woodland spaces, and it projects collective nature's reflection of us as being nuanced and mutable like us, indicating how we, too, might be strong yet vulnerable.