Rebel Forms, Romer Young Gallery

This review is part of our “Artist on Artist” series.

Chad Abbley is a working artist living in San Francisco.

By Chad Abbley

Late afternoon on opening night at SF Art Weekend 2026. Romer Young Gallery—my first time seeing it in person, though Erik Barrios-Recendez, the curator, had been my studio neighbor at Root Division before I left at the end of last year. The space is small in a good way, the kind of intimate scale I'd choose if I had a gallery myself: bright, clean, enough room to build an environment without feeling monumental. What caught me first was the lighting. Then Ana Teresa Fernández's Coatl, positioned in the corner, bridged the back wall and the left wall.

I didn't read the press release before I went. I wanted to see what the work did before I heard what the intention was behind the show. What I got was visual cohesion—a woven through-line connecting the pieces, a shared sense that these things had been constructed, built rather than just painted. Nearly everything was fully abstract, but Facundo Argañaraz and Julio César Morales had subtle photographic elements embedded in their work, just enough representational imagery to make it a 98% abstract show. That 2% felt intentional, a small contrast that makes everything else sharper. What struck me most was how solid everything felt. These didn’t feel like precious objects. They had weight, utility even. The weaving in particular—there's something about that technique, the way it's built to last generations, that felt like it connected to something bigger than formal experimentation.

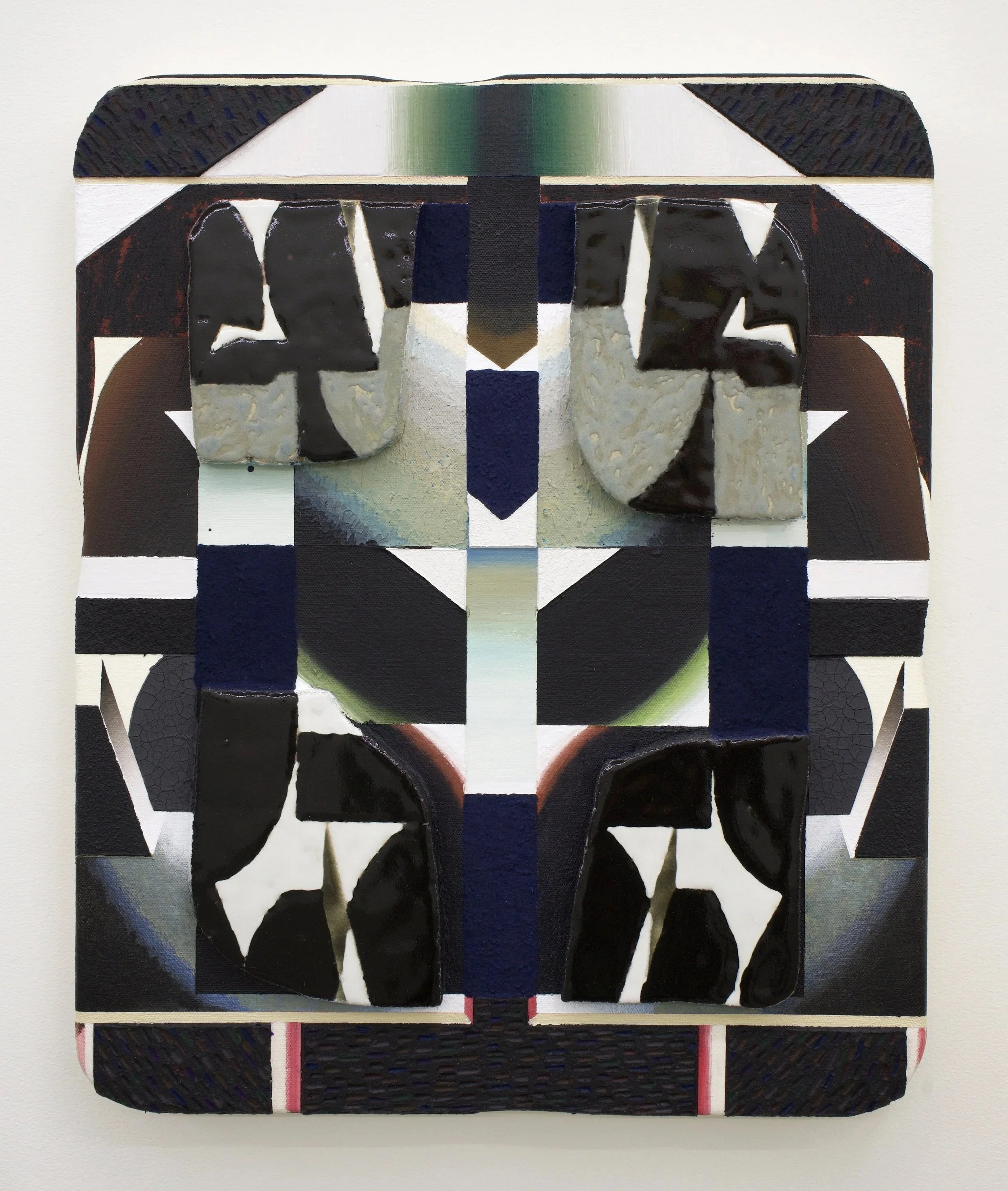

Kevin Umaña's Night Driving With Halo Around Lights and Increased Glare hit me with its dimensionality. Ceramic pieces—fired separately, then attached to the canvas-wrapped panel—protrude from the surface. I build my own canvases, so I noticed the radiused corners immediately, that level of craftsmanship. This is assembled work. Multiple processes happening separately, then brought together.

The textured paint used does something specific: it acts as an intermediary between the smooth gradients of paint and the ceramic elements jutting out. The piece moves through a full tonal range, white to black, high contrast hitting both ends of the spectrum. It's about transitions—smooth and abrupt, gradation butted up against hard edges. There's symmetry too, almost like a controlled Rorschach test. The ceramics reference chrome on cars, the refraction of streetlights or a sunset on a glossed finish. They feel like they shouldn't belong on the surface of a painting, but they're camouflaged in through patterning. Floating but integrated. Foreign but fitted.

Even without literal weaving, there's a visual weaving happening, a pattern assemblage that speaks to the other works in the show. The piece holds contradictions: angularity and smoothness, the rigidity of the support softened by wrapped canvas, those radiused edges softening what would normally be sharp corners.

Pablo Guardiola's Sea Glass Wall is the densest thing in the room. A single brick—weathered—with sea glass embedded in concrete on top. Eight inches by four inches by two inches, sitting on a pedestal.

The brick is a building unit. In Latin America, bricks like this get stacked onto walls around homes, topped with broken glass bottles. Sharp edges meant to keep out intruders. But this glass has been tumbled by the ocean, transformed over years from something that could slice skin to something safe to touch. The threat is softened.

Transformation takes time. Glass doesn't become sea glass overnight. The ocean works it against sand and rocks, wearing down sharpness year after year. What was dangerous became harmless. What was meant to wound becomes something you want to look at, maybe even touch.

A single brick doesn't make a wall. Alone, it's not protection. Here it's removed from function entirely, placed in a gallery as an object of contemplation. The materials are hard—brick, concrete, glass—but there's something almost edible about it. Like a small cake, the concrete reading as frosting, those smooth green and brown glass fragments catching light on top.

Standing in the gallery, I kept thinking about what's happening outside of it. Art week brings the community together, which San Francisco needs right now. But there was something in the air that night—the suppression happening across the country, colleagues and neighbors being targeted.

The show is framed around abstraction as rebellion. I kept coming back to that. The work's refusal to be immediately legible does something direct protest can't. It operates in a different register, filling different gaps.

I'm a white painter born in America. My perspective isn't the same as the artists in this show. But I can see what the work is doing. These are my neighbors and my friends. The formal strategies—opacity, construction, that refusal to perform identity clearly—those translate. Those make sense to me, even if I'm seeing them from a different angle.

What matters is that the work doesn't ask permission to be complex. It doesn't clarify itself for easy consumption. In a moment when people are being forced to prove belonging, to show papers, to make themselves legible to systems designed to exclude them—there's something to making work that refuses that demand.

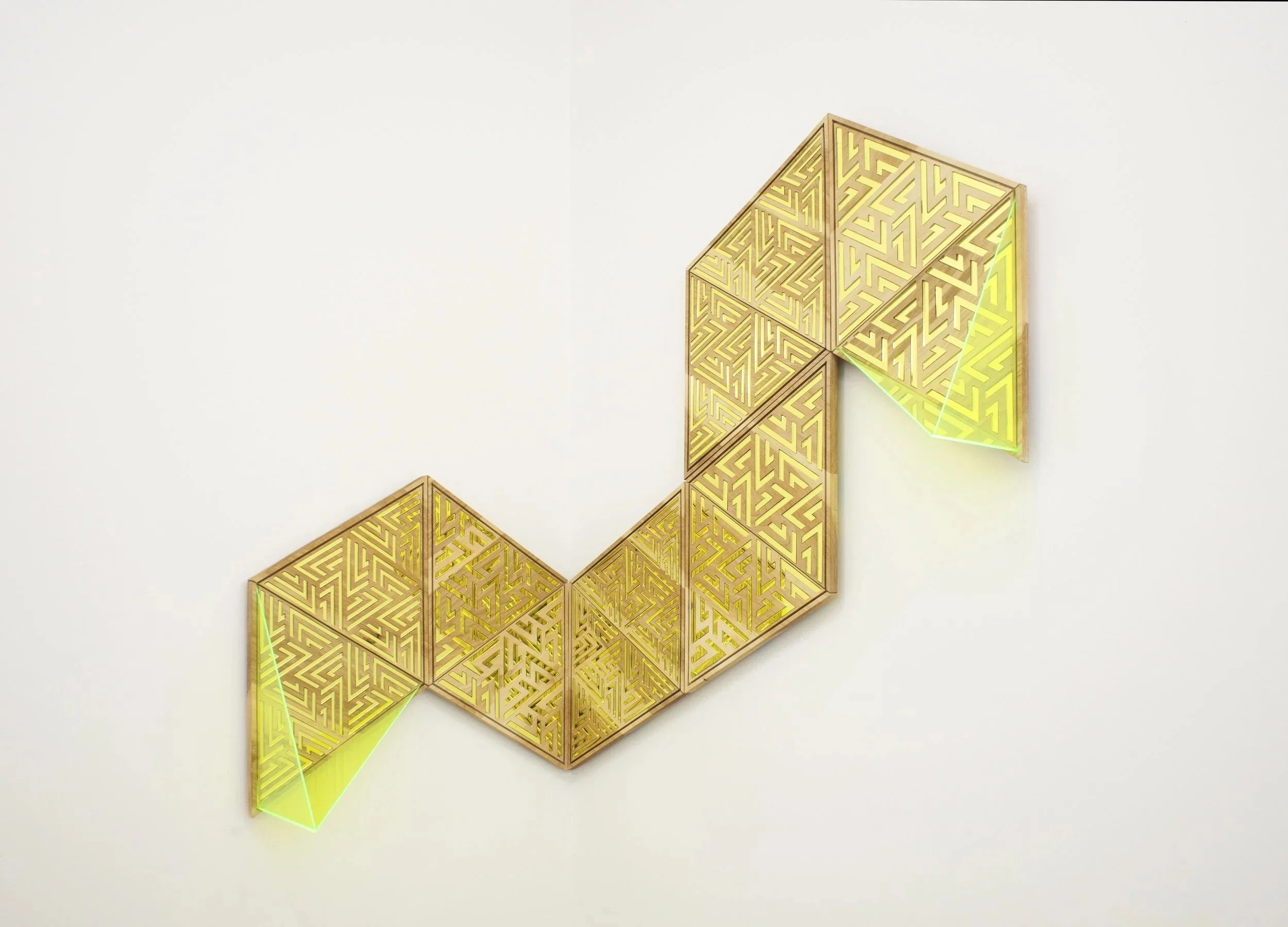

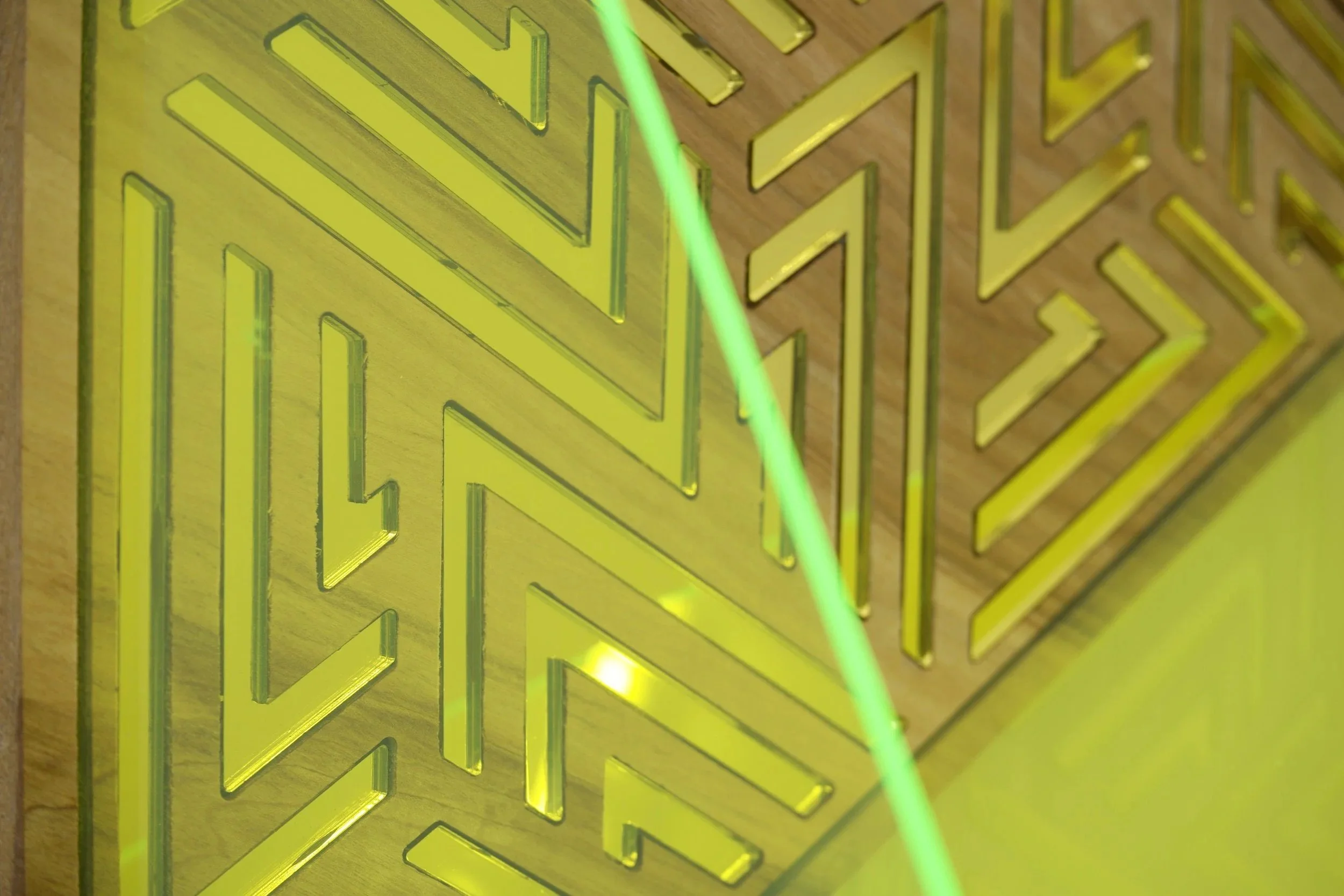

Ana Teresa Fernández's Coatl was the first piece I saw walking in, positioned in the corner, bridging two walls. Wood and plexiglass forming a geometric snake, triangular segments that reference structural reinforcement—the kind of bracing that makes buildings strong. The inlaid pattern connects to the weaving in other works without being literal about it. Repetition, rhythm. The plexiglass at either end catches the ceiling light, filters it, casts color down onto the wall. The mirrored finish reflects whoever stands in front of it. I wasn't expecting to see myself in it, but there I was.

Detail: Coatl , 2025, Ana Teresa Fernández

wood and plexiglass

42” x 60” courtesy : Romer Young Gallery , San Francisco

What stuck with me, leaving, wasn't heaviness. It was something closer to agency. A reminder that there are multiple ways to operate, multiple strategies available. Abstraction does work that other forms can't—it creates space that resists relaxed categorization, refuses to simplify itself.

These pieces are built to last—woven, constructed, assembled with care. They'll outlast the exhibition, outlast this political moment. Having different ways to tell stories, to communicate ideas. That's why work like this is as important as ever. Abstraction allows that.