Alternating Currents: Austin Thomas and Nick Polansky, Municipal Bonds

Austin Thomas and Nick Polansky were paired, a Municipal Bonds’ gallery sitter was telling each gallery entrant when I visited, because both create work using found or reclaimed materials. The two bodies of work, on view through February 28, also–unmistakably–share a vibe, suggesting additional commonalities.

The gallery’s main space contains five of Polansky’s sculptures at its center and 16 of Thomas’ monotypes, arranged in groups of five, plus one diptych on its own, lining the walls. A side room houses two central sculptures, plus three prints on two opposing walls. In classical ballet, the stage picture consists of principal dancers surrounded by the corps de ballet; here, the setup is similar.

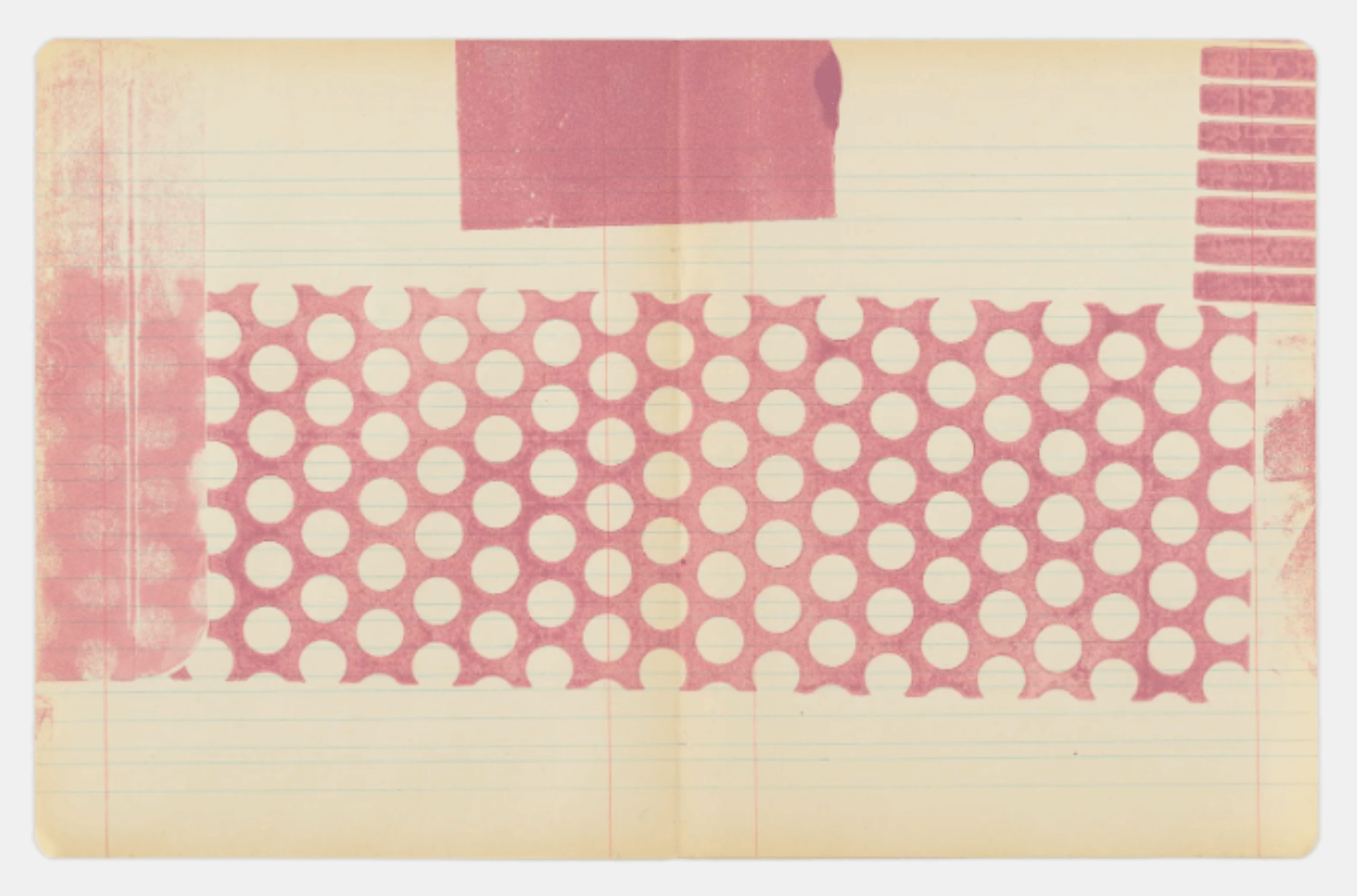

Thomas’ monotypes are printed on all sorts of papers, including notebook paper, Pantone paper, yellow legal pad paper, and proofing paper. Although all of the prints are based on a single vocabulary of shapes--rectangles, triangles, circles, ladders of stripes—alternate groups of monotypes take up different compositional strategies.

One set of prints from 2024 makes lined notebook paper the background pattern and inks over it in a single color. In these prints, shapes overlap only a small amount or not at all. Instead, each form, including some having an origin in the detritus of everyday life, is treated as a member of a collection of treasures (a specimen, if you will). In some of these prints, the shapes appear randomly pinned; in others, they coalesce into a super-form.

The prints on Pantone paper are, by definition, color-on-color, and they tend to lean into that, pushing shape after shape, in different colors, one over another. An unusual print on vintage ledger paper features a cloudy gray layer between, at the bottom, a yellowing, green-lined background, and, on top, a three-by-three pattern of pink quasi-rectangles that resemble pieces of packing tape, torn from a roll. Two mostly grayscale diptychs arrange their partially fractured shapes as if they were interacting, possibly having a conversation, early twentieth-century style.

Thomas plays with shapes as a kid might with blocks. Eventual viewers are not a concern; what Thomas is thinking about is what she has found and what she can do with it. It’s an approach that results in prints that radiate a refreshing, unforced purity.

Polansky’s sculptures are made primarily of various types of reclaimed wood—mahogany, white oak, cedar, walnut--mounted on improvised metal stands. A few pieces include non-wood materials such as copper pipes or flat stones. In all of the works, wood is foregrounded, and the material is always cut, whether to create lines by removing pieces or to separate it into strips.

In several works, the wood is shaped into compositions sharing a degree of ambiguity that is unusual in sculpture. Split no. 21 (2025), made of white oak and copper pipe, is placed on the diagonal of its podium. The work doesn’t have a clear front, but, because it is also not 360-degree-symmetrical, it provokes the viewer into searching for one. Turbine no. 04 (2025), made of nearly paper-thin cedar slices, starts with the soft beauty of the wood, then adds the grain, which produces large painterly streaks, and finally creates an accordion-like structure with vertical, elongated, half-lenticular openings that are regular until one suddenly yawns wide open.

Grid no. 13 (2025), made of mahogany, resembles a flattened skyscraper. Its secret is strips of missing wood in a horizontal direction on one side and in a vertical direction on the other, creating a lattice. In the small room, two Waffle works are variations on a theme, as in music. One mahogany slab, more than five feet tall with its stand placed on the floor, features narrow lines of missing wood on its broad face, which, because of how they are spaced and the fact that they extend about three-quarters of the way through the wood, create zigzag patterns on the edges of the slab. A smaller slab, about two feet in height and resting on a tall podium, features cuts from either narrow side, placing the zig-zag on its broad face.

Then there are the two eye-catching Splay works. These consist of blocks of wood that have been cut into strips above an uncut base and forced to fan out by flat, oval stones wedged between groups of strips. The works’ simultaneous evocation of freedom and restraint lends them an erotic air. Another contrast: the lightness of the cut wood and the heaviness of the stones. These works share unexpectedness with other sculptures in the show–but diverge from those works in their 20/20 legibility.

There’s an experimental ethos behind Polansky’s works that rhymes with Thomas’ playfulness. The sculptures try new things, and they are not afraid to be strange. But Polansky’s work has more of a plan, more cleverness. It also has less interiority, addressing its viewers directly.

The vibe between these two bodies of work has multiple sources. A good part of it derives from how seriously Thomas and Polansky treat their found or reclaimed materials. For both artists, two things interest them equally: the beauty they have come upon, and their own interaction with that beauty. Both Thomas and Polansky make use of mechanical tools, be it the press or the saw, and both compose their works from simple, fundamental shapes. Both Thomas and Polansky speak quietly; their audience leans in to listen.