Marie Wilson, A Poet of Colors and Forms, Gallery Wendi Norris

This exhibition runs January 20 – March 14, 2026

Cedarville, CA-born Marie Wilson (1922–2017) is an artist I first turned onto through the advocacy of Philip Lamantia (1927–2005), the preeminent U.S. surrealist poet, welcomed into the movement in 1943 by André Breton in the pages of his WWII magazine-in-exile VVV. Breton included Wilson in a 1955 group show he staged at L'Étoile Scellée in Paris. He also owned at least one of her paintings, which appears, frustratingly undated and "sans titre," in the catalogue for the 1991 Pompidou exhibition, André Breton: La beauté convulsive. Lamantia's own brief comment on her work, apropos her 1984 show in the basement of City Lights Books, Apparitions: The Mythical World of Marie Wilson, is reprinted in Preserving Fire: Selected Prose of Philip Lamantia (2018).

This pedigree should have ensured at least some measure of artistic fame, but on the whole, like many women of the surrealist movement, she received little attention or notice in her lifetime, to the point where she was overlooked by the otherwise scrupulously thorough LACMA show In Wonderland: The Surrealist Adventures of Women Artists in Mexico and the United States (2012). The fact that an exhibition seemingly tailor-made for her eccentric trajectory (she divided her later years between Athens, Greece and Oakland, CA) didn't include her work was less a curatorial failure than an indication of how inaccessible that work has been. She only occasionally exhibited, seldom made prints, and was most likely to be encountered illustrating a poetry publication, be it a surrealist edition like Terre de diamant (1958)—a collaborative book with her husband, the Greek surrealist Nanos Valaoritis (1921–2019)—or, intriguingly, issue 6/7 of the pioneering gay poetry magazine Manroot, which contains her portfolio of drawings Psychograms (1972). The difficulty of tracking down information about her, moreover, is compounded by her relatively common name; search for "Marie Wilson" online and you're far more likely to land on, say, a member of the Supremes. You might get UK Prime Minister Harold Wilson's wife, who fancied herself a poet, even though her actual name was "Mary." But mention of the American surrealist herself remains scant, online and elsewhere.

Nonetheless, as a young artist in the late '40s, Wilson first meets up with members of the surrealist spinoff group Dynaton, including Jean Varda and Gordon Onslow Ford. She becomes partners with Wolfgang Paalen, moving to Paris with him in 1952. Accepted by Breton into the movement, she weathers a brief period as Picasso's studio assistant, before meeting and marrying the Greek surrealist poet Nanos Valaoritis in the mid-'50s. In a sense, the works of this early period—all of which are dated 1952–1954, before her artistic breakthrough—are responsible for the present exhibition, for a substantial cache of early paintings was discovered in the basement of the couple's Paris apartment after their deaths. For the first time, we're given the opportunity to see something like her chronological development as a painter.

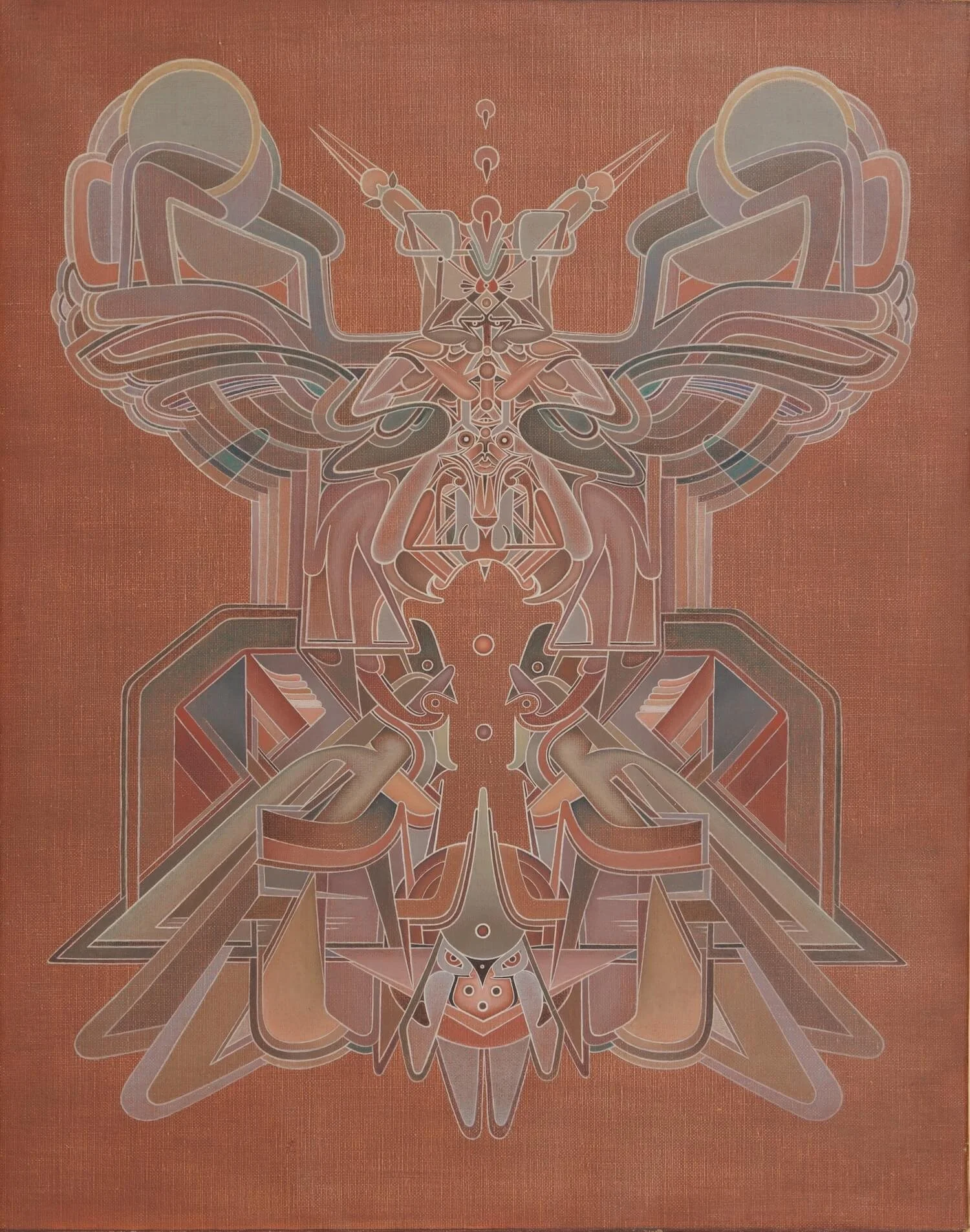

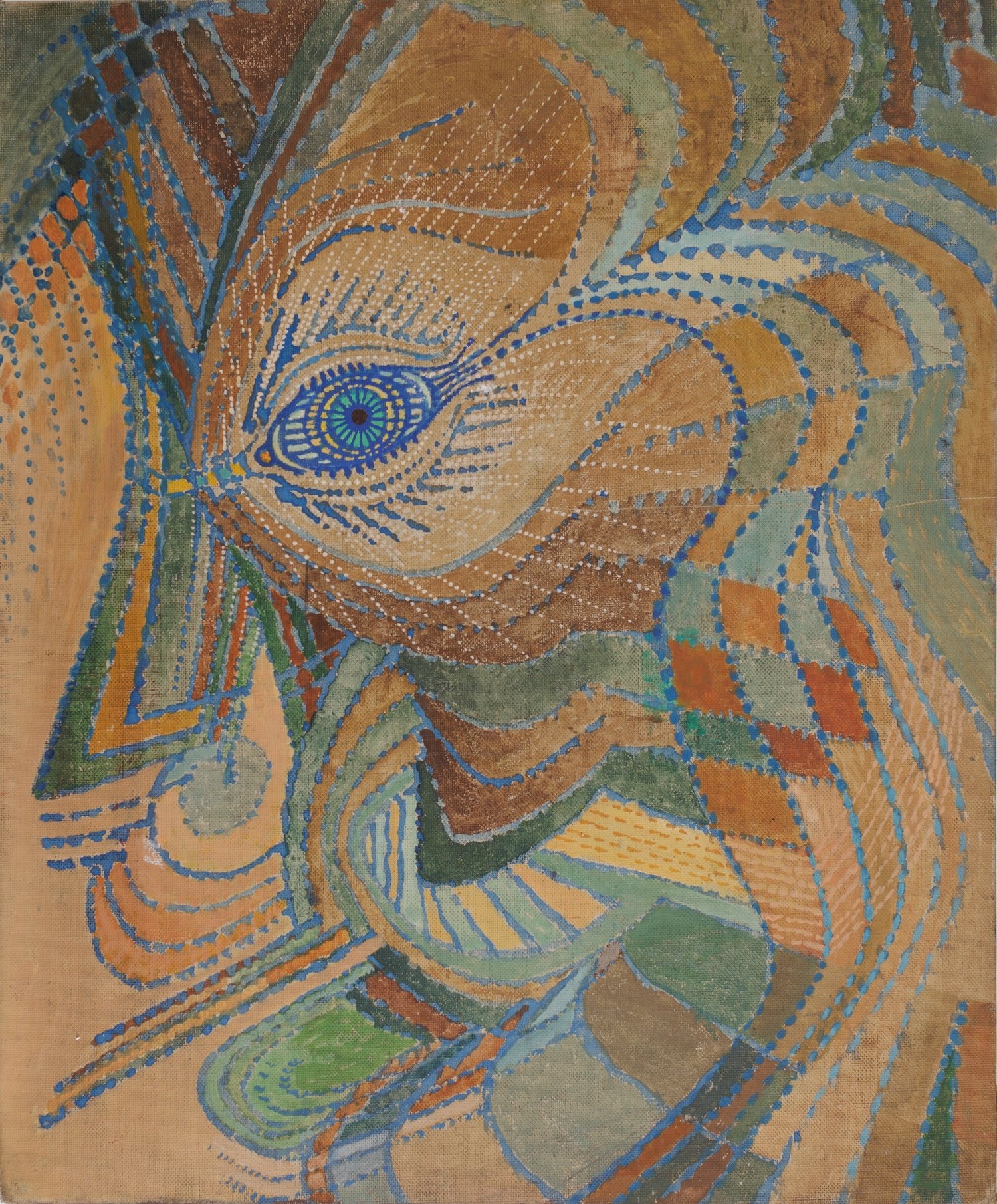

Some of these early paintings—Creation of the World, for example, or Going Back in Time—tentatively allude to Paalen's art, but not slavishly so. But the more accomplished ones—Cedarville, let's say, or Perpetual Revolution—evoke the art of Onslow Ford or Roberto Matta, even as they point to the evolution of her own distinct mode. To take Perpetual Revolution as an exemplar, within its swirl of fragmented lines appear three roughly symmetrical "figures," for lack of a better term, the leftmost of which nearly spans the height of the canvas. By 1957, however, as represented here by The Birth of the Celestial Monkey, Wilson has hit upon the distinctive manner that she will spend the rest of her artistic life exploring, centering the figure and engaging in a rigorously symmetrical pursuit of her surrealist vision. She deviates from this only rarely—as in Psychograms' portrait of Valaoritis, The Poet's Head, not included here but bearing a more-than-passing resemblance to the early Portrait of the Poet in a State of Delirium—finding more than enough to explore in her chosen approach. As we can see from paintings like Rites of Passage (1957–1958) or Sunrise Prophecy (1964), it doesn't always make sense to consider these images "figures" at this point, though figurehood doesn't entirely vanish, as made plain in drawings like Snow Woman or Minotaur (both 1970–1971).

At first glance, the deliberate compositional method and occasionally lengthy genesis of her works—one of which, Spirit of the North Star, is dated 1957–1981—seem to run counter to a surrealist movement better known for spontaneous, automatic generative principles, but clearly Breton didn't think so. That his sense of surrealism is expansive enough to include such symmetry is a point the aforementioned Pompidou catalogue makes through its juxtaposition of Wilson's "sans titre" with works by spiritualist outsider artist Fleury-Joseph Crépin (1875–1948); the kinship between these images is obvious at a glance, even though the circumstances of their generation—Wilson from the contemporary avant-garde and Crépin from the conviction that he received his art as communications from the dead—could be no more different. While Breton certainly encouraged automatic techniques, like fumage or decalcomania, he never insisted that surrealist visual art could only result from such procedures. As Wilson herself suggests, in a quotation reproduced in the gallery's promotional material, there is a type of automatism to be found even in works slowly built up over time. Always beginning in the center and mirroring every stroke of the brush or pen on one side of this center with a corresponding stroke on the other side, she likens her creative process to lacework, albeit with no preconceived pattern in mind. "I invent it as I go," she says. "I am not starting with an idea. I don't know where or what I am going to do when I begin a drawing or a painting."

There is still much to fathom of Marie Wilson's relatively compact oeuvre, which apparently numbers less than 200 works total. Her unusual choices of media—few of the oil paintings here are on canvas and more than one incorporates sand—call for further attention. That so fascinating an artist as Wilson can emerge at this late date, years after her death and well after the original Paris group's dissolution in 1969, moreover testifies to surrealism's perpetual relevance over the past 100 years, as well as its seemingly inexhaustible capacity to confront us with something new.