Pictures of Belonging: Miki Hayakawa, Hisako Hibi, and Miné Okubo, Monterey Museum of Art

By Robert Brokl

Picture of Belonging: Miki Hayakawa, Hisako Hibi, and Miné Okubo, the exhibition currently view at the Monterey Museum of Art through April 19, is timely in the extreme, not simply because exposure of the three featured Japanese American women artists is long overdue, but because the anti-immigrant oppression and racism in the 1940s that so profoundly affected their lives has returned in force.

This exhibit was curated by Dr. ShiPu Wang, art history professor at the University of California, Merced. The show has traveled from the Smithsonian Museum of American Art in Washington, D.C., and other venues, and moves to the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles after Monterey, its only stop in Northern California.

Bay Area Beginnings

The exhibit convincingly demonstrates that Miki Hayakawa (1899-1953), Hisako Hibi (1907-1991), and Miné Okubo (1912-2001) are significant contributors to American art history, and their careers began with their studies at prestigious art schools in the Bay Area: Hibi and Hayakawa at California School for the Arts (later San Francisco Art Institute, now shuttered), and Okubo at UC-Berkeley.

Okubo was born in Riverside, California., where she attended Riverside College. Hayakawa immigrated with her parents from Japan, and they settled in Alameda. She was married at 18 to an older man at her parents’ instigation but left her marriage to pursue art; Hibi also immigrated from Japan with her parents.

A rapturous review of the show by Aruna D’Sousa in the New York Times, Jan. 26, 2025, highlights the tolerant, nurturant quality they found in the Bay Area: “These three women — Okubo, a second-generation Japanese American, and Hibi and Hayakawa, first-generation immigrants — were all acclaimed artists in a remarkably multicultural San Francisco art world before the war. When Hayakawa’s work was featured in a big retrospective at San Francisco’s Golden Gate Institute just shy of her 30th birthday, she was called a genius by the San Francisco Examiner’s art critic, who was himself an immigrant from India. This milieu was all the more amazing considering it was happening during the decades of Asian exclusion, marked by laws that restricted Asian immigration, prevented Asian immigrants already in the United States from becoming citizens, and barred immigrants and citizens alike from owning property. (Some of these laws were only fully lifted in 1965.)”

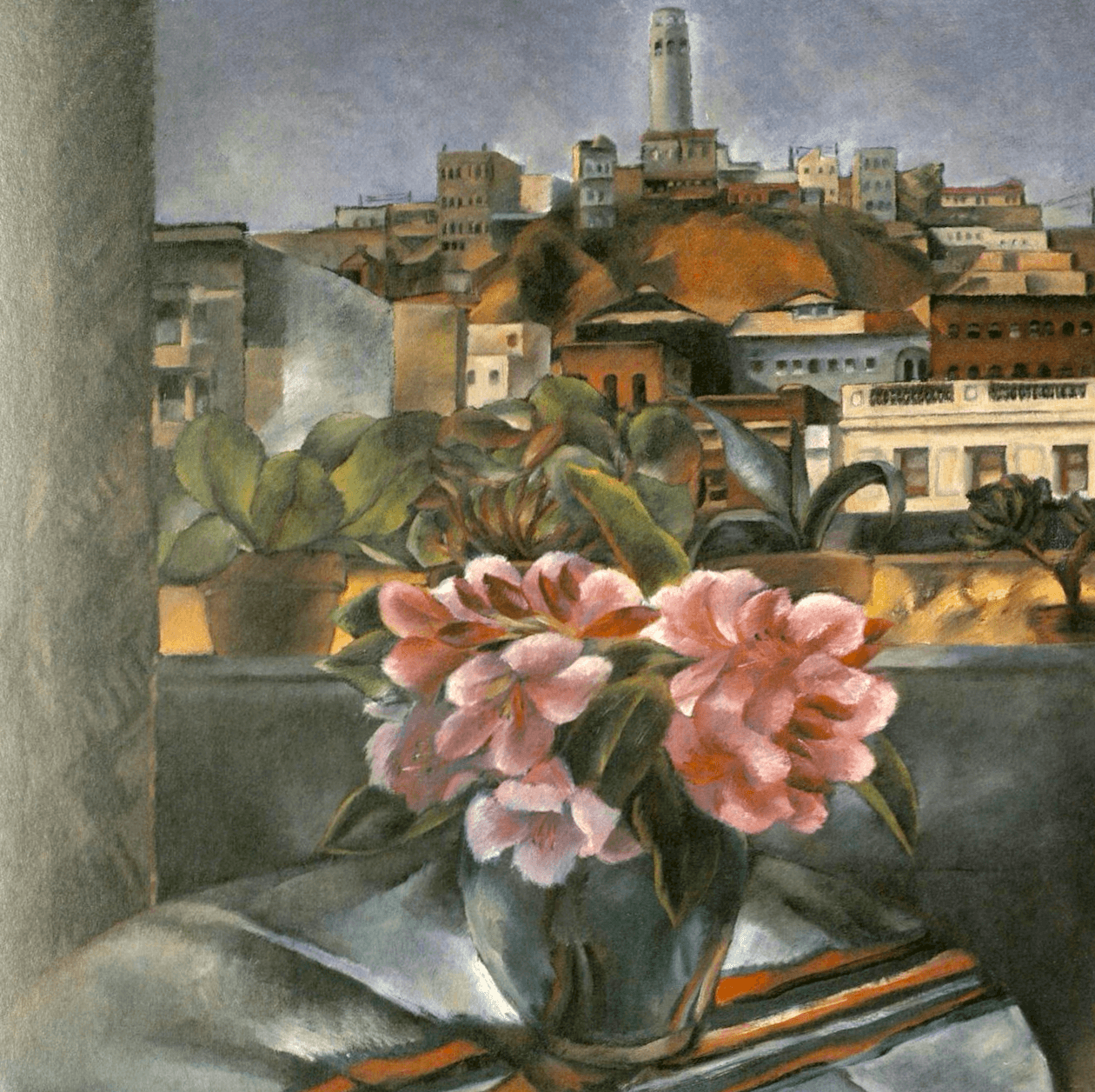

All three worked in a Western and realistic manner early on—Hibi depicting buildings and landscapes around her home in Hayward, Hayakawa producing skilled paintings of nude models— volumetric, muted fauve color, in a cubist/art deco/Bloomsbury blend of style, eschewing the coy salaciousness of a Tamara de Lempicka. A couple of loose portrait sketches of children are eerily evocative of expressive Alice Neel portraits. From my Window, a 1935 oil on canvas, currently on loan to the Huntington Art Museum, depicts with cubistic flattening a vase of flowers against a window with Coit Tower and Telegraph Hill looming in the background.

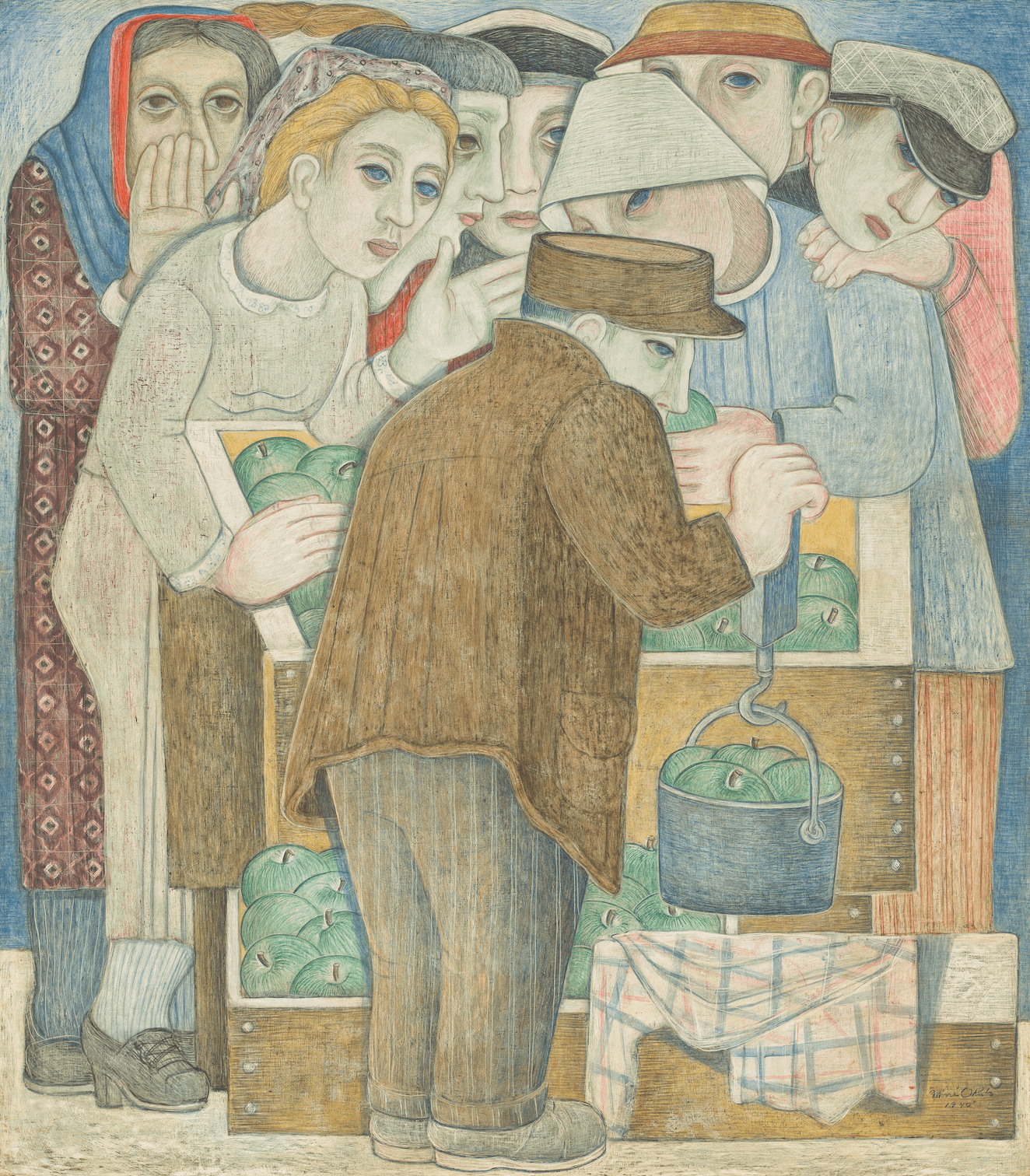

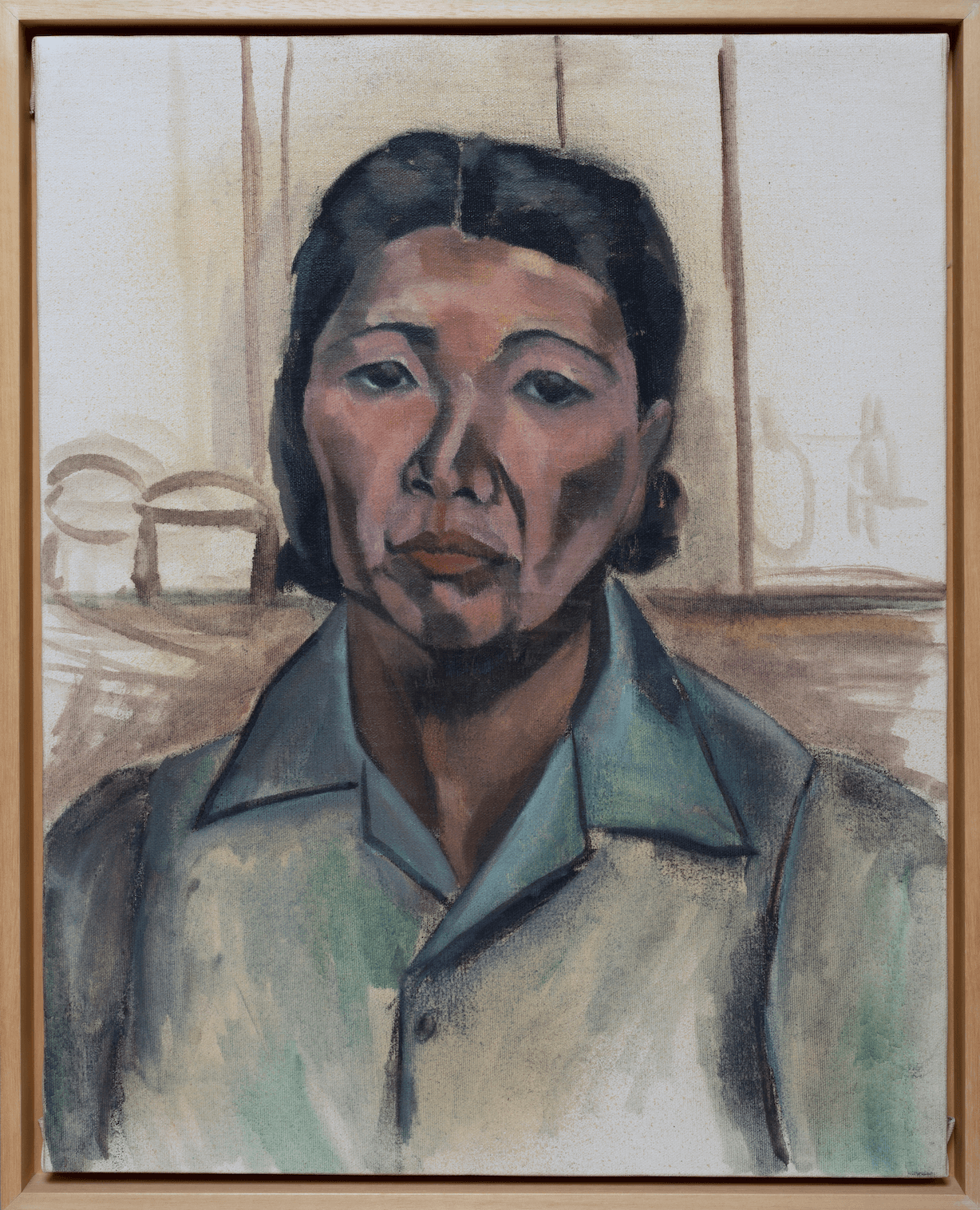

Their work was met with acclaim—Okubo won academic prizes and a traveling fellowship to Italy and France, where she studied with Fernand Legér, and Hayakawa was the only Japanese American woman artist included in the inaugural show at the new SFMOMA in 1935. Okubo was influenced by the Mexican muralists, Diego Rivera and José Clemente Orozco, reflected in her portraits on view (including a self-portrait loaned by the Oakland Museum of California), and subjects like Grocer Weighing Produce, tempera on hardboard, from 1940 (Smithsonian Museum of Art Collection), with flat solidity of the figures and colors of faded fresco.

Incarceration

Their lives were abruptly disrupted after the bombing of Pearl Harbor and President Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066, from Feb. 1942, that ordered the evacuation of 120,000 Japanese Americans, 112,000 from the West Coast, two-thirds of whom were American citizens. HIbi and Okubo were first sent to the converted Tanforan race track in San Mateo, where the new inmates were forced to clean out and outfit the horse stalls for living quarters, and then to the Topaz Relocation Center in Utah. Dorothea Lange photographed Hibi and her young daughter Ibuki on May 8, 1942, waiting to be shipped off with other detainees. It’s unclear whether Lange knew their identity. Hayakawa’s parents were both interned, but she moved to New Mexico and avoided the same fate.

The works that Hibi and Okubo managed to create in the camps are not just diaristic documentation, but triumphs of resilience and pluck, in similar grim circumstances like Charlotte Salomon and Max Beckmann hiding from the Nazis in Europe. Hibi made small canvasses of barracks and barren terrain in gray washes of oil paint, such as A Bathroom, 1945; only the still lifes of produce and flowers grown by the internees themselves from the infertile soil have more positivity. The vivid red sunrise in Eastern Sky 7:50 A.M. Feb. 25, 1945, collection of Japanese American National Museum, suggests her personal turmoil and emotions. She and her husband, artist Natsusaburo “George” Hibi, conducted art classes at Topaz, along with Chiura Obata, who had been removed from his position as a UC-Berkeley professor; George Hibi and Obata had both belonged to the East-West Society in 1921-2.

Life After

Okubo made drawings of the residents coping with the harsh conditions, and in 1946, she published her epic Citizen 13660, a graphic novel illustrating her camp experience. She had been released from the camp early, having been offered a job with Fortune magazine illustrating their April 1944 Japan issue. She spent the rest of her life living in New York City, 60 years in a rent-stabilized apartment/studio in Greenwich Village, making a living as an illustrator and then concentrating on her painting.

Hibi and her husband were among the last to leave the camp, moving to Hell’s Kitchen in New York City in 1946, which, from her artwork, appears not much of an improvement over their previous grim circumstances. She and her husband both developed cancer, and he died in 1947. She resettled in San Francisco and became celebrated with accolades and honors, including San Francisco’s official Hisako Hibi Day on June 14. Her day job was as housekeeper to Marcelle Laubaudt, dismissed as a “socialite” on the wall label, but the reality was more interesting: as the widow of muralist/art war correspondent Lucien Labaudt, Marcelle Labaudt established the art gallery in his name, which lasted from 1943 until 1980, giving shows to young artists, such as the two person Richard Diebenkorn and Hassel Smith sculpture and painting show in 1950. Hibi used the garage as her studio.

Hayakawa settled into the Santa Fe arts community, her palette brightening with the Southwestern climate and landscape. She continued with portraiture. Three of her earlier portraits of a young man remembered only as Edward are clustered together at one entrance to the exhibit, including the large (40” square) painting One Afternoon, circa 1935, now in the New Mexico Museum of Art. A male figure lounges casually on the floor, surrounded by mounds of fruit, cala flowers with prominent pistils (Georgia O’Keefe wasn’t the only one to notice their erotic symbolism), and curved stove pipe which underscore the sensual atmosphere. In the other two, Edward wields a saw and plays the ukulele.

In Santa Fe, Hayakawa married and melded into the artistic community. Unfortunately, she died quite young in 1953, “with no biological children and no estate trustees.” A Santa Fe gallery showed her work in 1985, which then became scattered.

Both Okubo and Hibi developed mature styles that one might not have expected from their earlier work. Hibi’s Buddhist beliefs seem to have given her detachment about her interment and lightened her art—the washes of color are now predominantly yellow, calligraphic letters, figures, and nature appear in the vapor. Given her history and training, these cannot be dismissed as decorative abstract color fields, but rather existing in the spiritual tradition of other Northwest School artists like Mark Tobey. Autumn, a large oil on canvas from 1970 in the collection of the Smithsonian Museum of Art, is a fine example of her late work.

Okubo, too, made a turn. Paintings like Clown and Horse, from the early 1950s, reflect the influence of Picasso; later still, work like Boy, Goat, Fruit, acrylic on canvas, before 1972, collection Riverside Community College, are called “childlike” for their bright, bold forms, but are perhaps more indicative of artistic simplification and reduction that may come with age, i.e. Matisse with paper and scissors. Many of the loans for the exhibit came from 8,000 objects of the Okubo estate at the Center for Social Justice & Civil Liberties, Riverside Community College District.

Epilogue and Alert

Pictures of Belonging is much more a celebration and showcase of well-deserving artists, even if late in coming, than a depressing “if only?” or “what if?” Scholars such as ShiPu Wang are to be congratulated, but their work is cut out for them: the Hibis, for instance, left their work behind to a Hayward neighbor when they were interned, but the neighbor died in 1954, and the work disappeared. Two examples of Hibi’s work from 1940 were discovered in the collection of the Hayward Historical Society and appear in the show. It’s heartening that important institutions like the Smithsonian Museum of American Art, the Oakland Museum of California, and the Japanese American Museum of Art own works by these artists, and lent them to the show, but where are NYMoMA or SFMOMA, LACMA, the Whitney? And widening the lens, it’s not that better-known, even among international artists like Yasuo Kuniyoshi and Fujita Kuniyoshi, Japan-born expats who straddle cultures and continents, who aren’t interesting but are still marginalized. Maybe the canon’s not quite as open as we would like to believe.

Also alarming: with the wholesale disruption of communities, especially people of color, in the current drastic immigration disruption and expulsion, what other artistic contributions are being destroyed, and careers blighted?

Celebrating California Art: Artistic Alliance in Monterey, 1942-1946

A small but valuable show in the museum’s Currents Gallery, guest curated by Jane Dini, highlights the Monterey community reaction to Executive Order 9066 (1942), including petitions signed by local artists and writers asking for the return of their former neighbors, and artwork by artists from the area, 1943-46. Many Japanese Americans who were rounded up had been intrinsic to the arts, fishing, canning, and agriculture of the area.