Wayne Thiebaud, The Unknown Thiebaud: Passionate Printmaker, SebArts

LINES ON WAYNE THIEBAUD @ SEBARTS

“Lightning bolts seldom come down from the sky, but one thing does lead to another, so ideas recur, and changing anything changes everything.” Wayne Thiebaud

Remember the children’s book Harold and the Purple Crayon? In portraying the imaginative adventures of a four-year-old boy who is the single artificer of his world, the author and illustrator Crockett Johnson also tells the story of how art is made. It begins with a simple act: drawing a line and being curious about where it will lead.

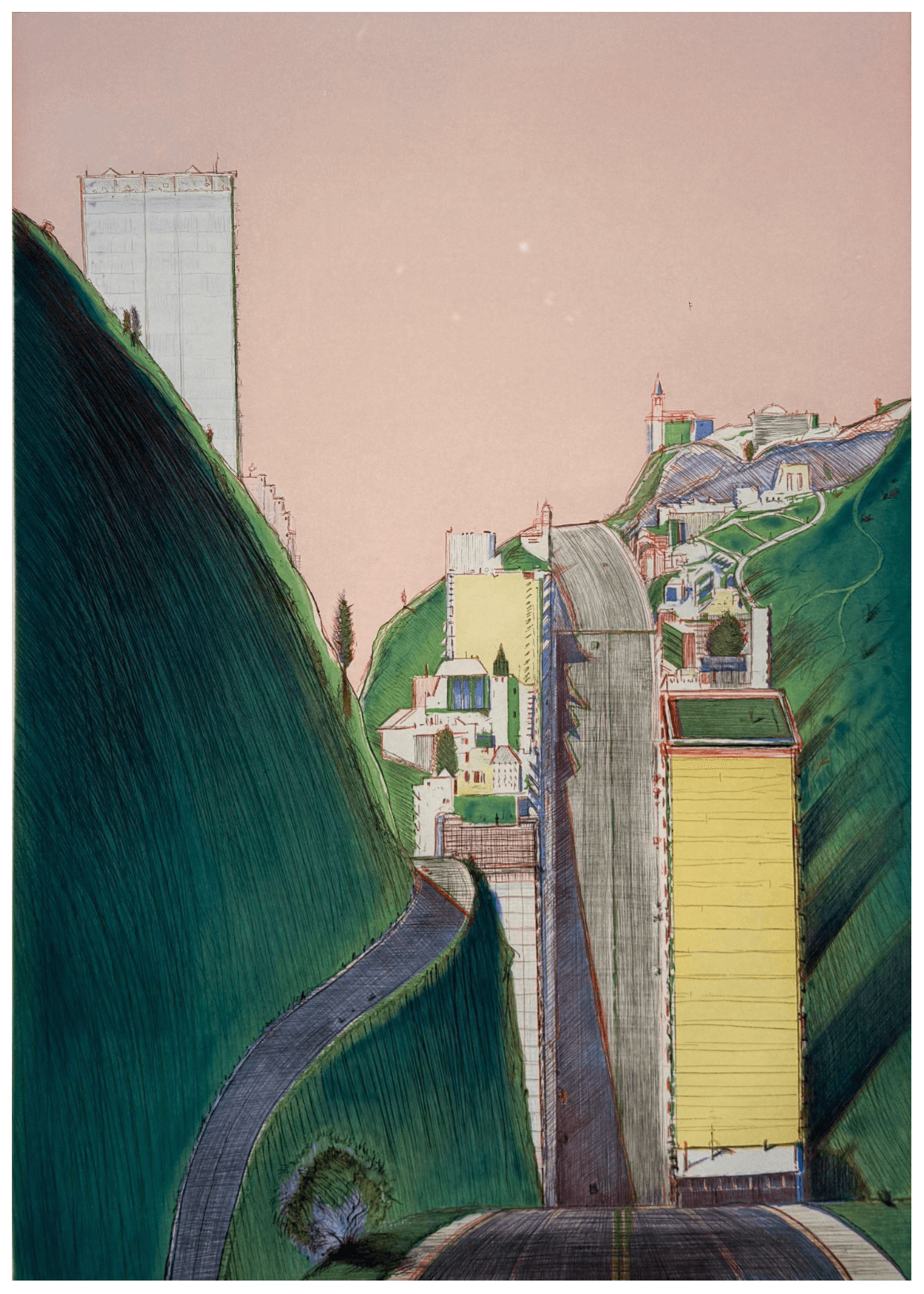

The simplicity of cakes, cones, counters, cliffs, and cityscapes solved a problem for the artist Wayne Thiebaud. They allowed him to draw a line and follow his curiosity. Thiebaud was interested in how ordinary things become extraordinary. Scenes of simple geometry allowed him to slow art down to its most basic grammar in order to experiment.

Though his ebullient paintings often overshadow his printmaking, the process was central to how he thought about the mechanics of seeing. Printmaking allowed him to probe the questions that first drew him to desserts as a motif of image-making: how an image is built through layers, how repetition sharpens perception, and how small shifts in color or pressure can radically change what we notice.

Curator Alan Porter has assembled six decades of printed artwork to showcase Thiebaud’s lifelong pursuit of printmaking for an illuminating exhibition at the Sebastopol Center for the Arts. The show titled “The Unknown Thiebaud: Passionate Printmaker” presents over 60 prints, along with hand-colored prints, paintings, and pastels. Throughout, the exhibition illuminates Thiebaud’s “critical interrogation” of line and form, as well as his unusual working methods. It traces the artist’s transposition of triangles, squares, ellipses, and spheres through varied techniques to achieve results that feel fresh and dynamic.

An additional bonus is the element of Thiebaud’s storied relationship with legendary New York gallerist Allan Stone, who gave Thiebaud his first major show and represented him for over 45 years. Four of Stone’s daughters have loaned work for the SebArts show, and The Collector, Olympia Stone’s excellent documentary about their father, will be screened on February 28.

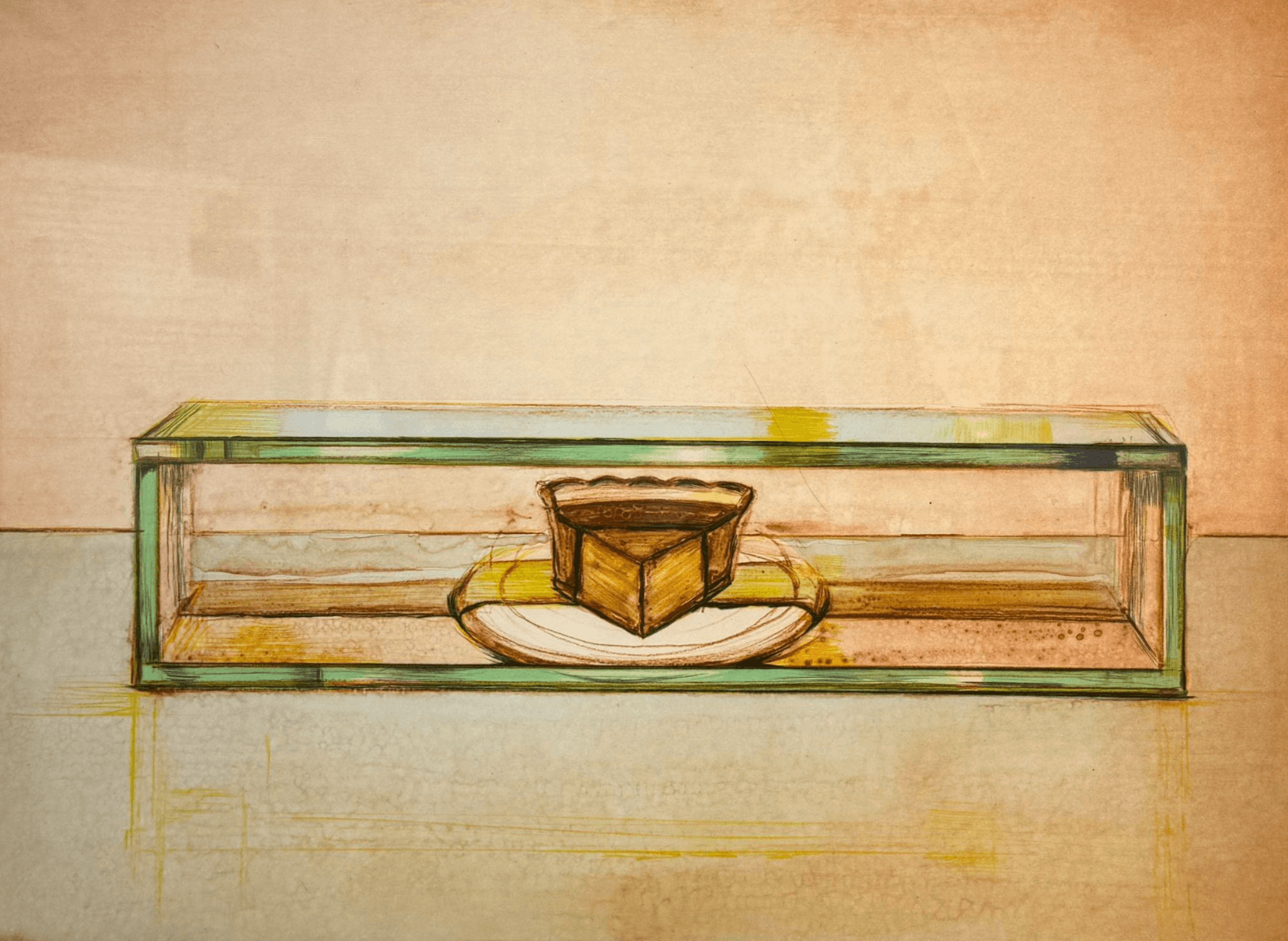

Thiebaud’s long and fruitful collaboration with Crown Point Press is also on display. The relationship began in 1964, with the “Delights” series of etchings. 10 of these 17 iconic food-themed ethics are represented in the exhibition, along with 2 copperplates that were never printed. The artist and the press continued working together until 2021, shortly before Thiebaud’s death at age 101.

The exhibition makes abundantly clear that his prints weren’t just translations of paintings; they acted as a parallel practice where his ideas became sharper, more novel, and more graphically articulate. The slow accumulation of marks in etching or the greasy crayon of lithography echoed his belief that drawing was foundational, in other words, that images emerge through disciplined looking rather than invention.

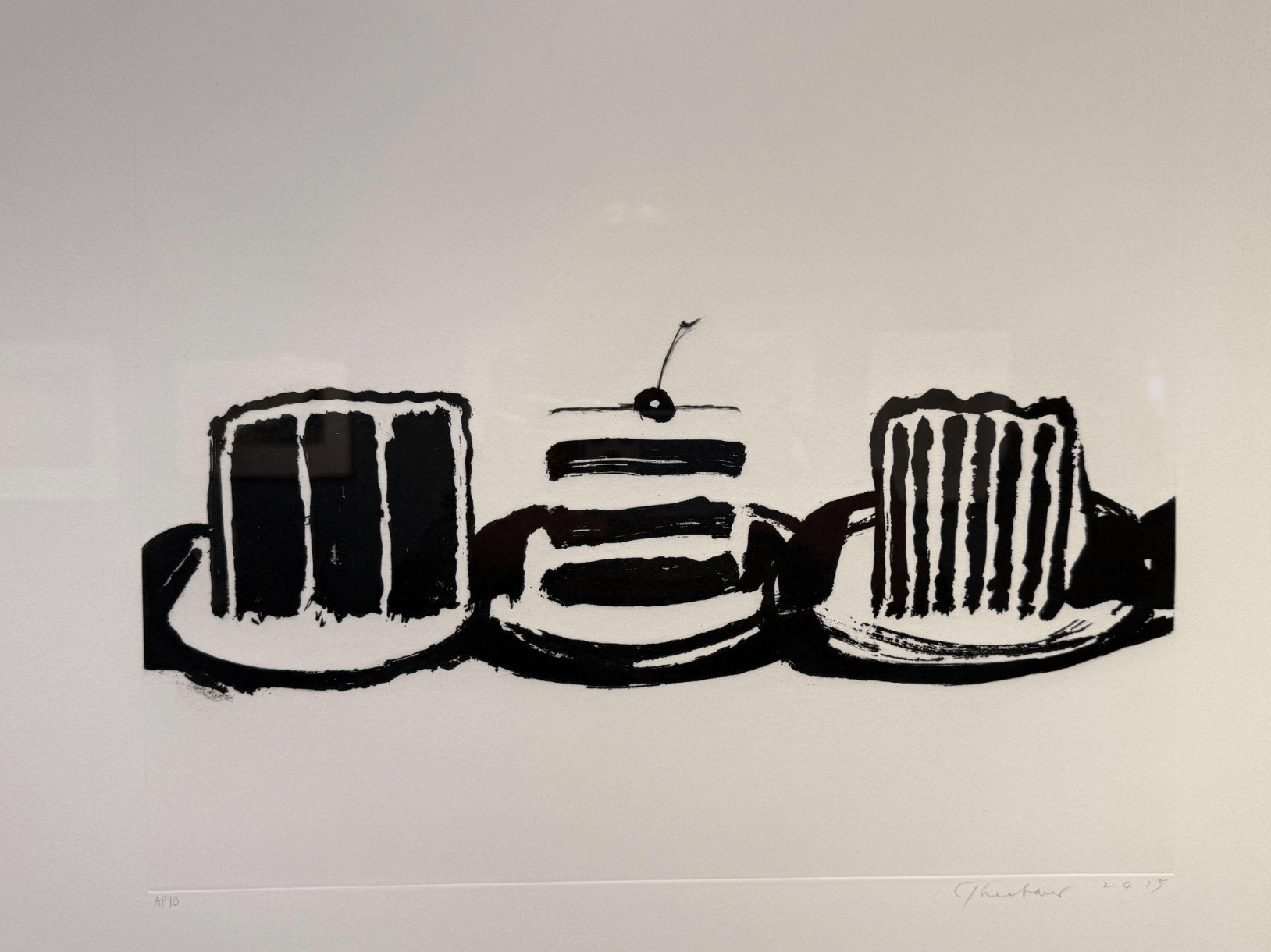

The foundational importance of line is evident in Thiebaud’s etchings and lithographs. Contour goes to work to create thick, deliberate outlines that stabilize forms and give objects their clarity. Printmaking amplifies the reliance on line because every mark must be either cut into a plate or drawn onto stone. Line articulates both boundary and architecture.

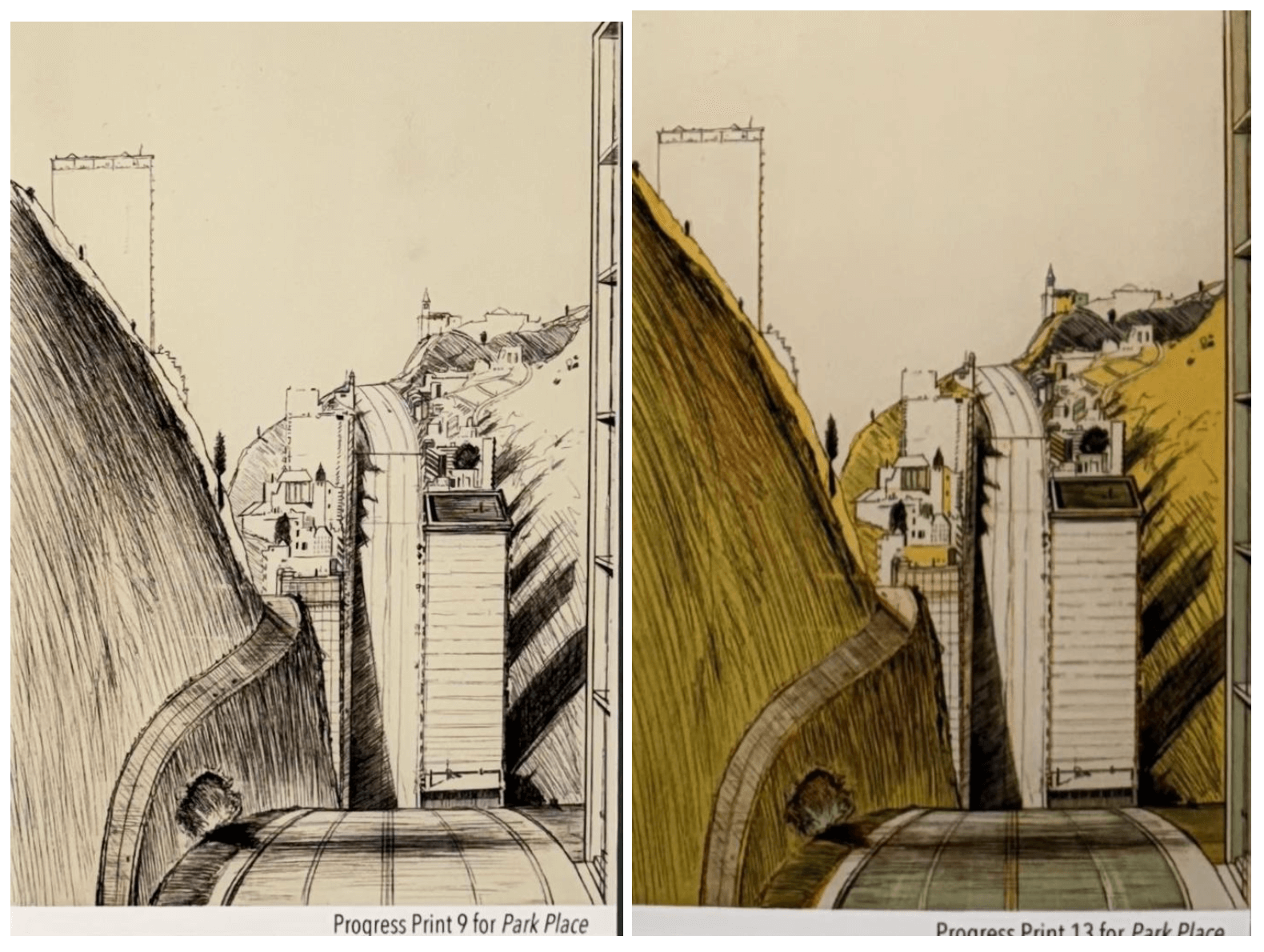

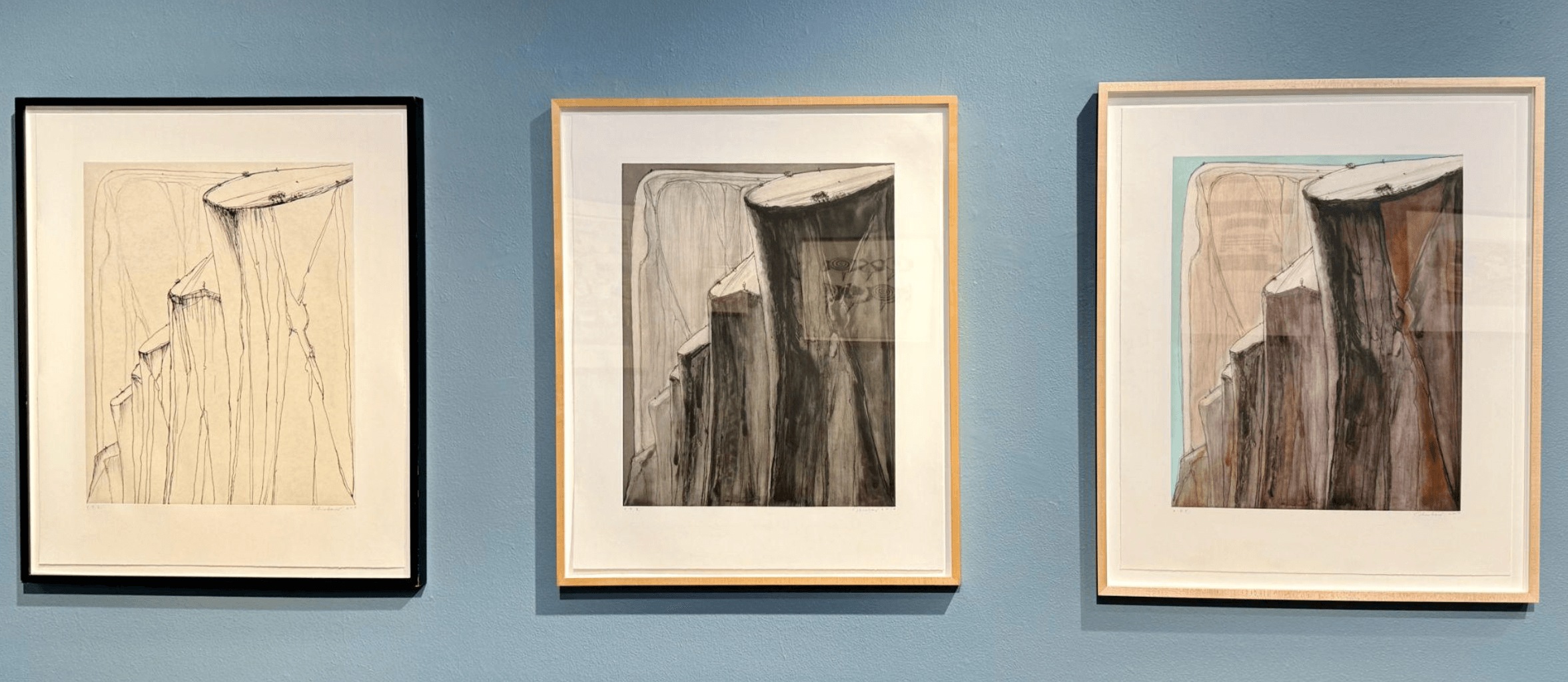

Images of all progress prints are courtesy of Crown Point Press

The centrality of repetition and variation to print culture aligned perfectly with Thiebaud’s interests. Multiple states and editions allowed him to tweak a single image incrementally, isolating what changes when a line darkens, a color shifts, or a shadow slides. This serial thinking reinforced his belief that perception is built from small, repeatable decisions. In progress prints 9 and 13 for “ParkPlace”, we see Thiebaud go much farther than adjusting a detail or reconsidering a color change, he crops the right side and bottom of each of the 6 plates used to make the print, in order to erase a building and shorten the road in the foreground, making the result a more vertiguous and dramatic experience for the viewer.

Thiebaud uses repetition like a refrain, returning the eye again and again to familiar forms quietly transformed. Arrays of cakes or shoes unfold in measured sequences, where likeness gives way to variations of light, shadow, and surface. Through printmaking, Thiebaud pares his subjects down to line and tone, allowing texture to emerge across the paper. When the dense, frosted weight of his painted desserts is translated into the spare language of print, repetition becomes a critical method of attention.

Repetition occurs in space across Thiebaud’s rows of objects, as well as across time. Often, quite a bit of time. For instance, the show includes an early oil painting of a land cloud, to which Thiebaud returned 31 years later in a hard-ground etching and drypoint.

Printmaking, with its matrices, reversals, and sequences, is an art rooted in construction. It showcases technical and compositional elements that may be less clear in a painting. One of the great gifts of this exhibition is that it reveals the undergirding of Thiebaud’s tireless artistic process. It gives us a glimpse into how he worked and reworked. It shows us the places that his curiosity took him. It hands us a thread (a line) and invites us to follow.

It’s hard to pick a favorite from this exhibition’s rich trove, but have a look at “Van, 1989,” an etching hand-worked by the artist with colored pastel pencil. It’s a wonderful example of how Thiebaud used crosshatching to create the sensation of movement. There’s a jumpy quality to the air, the vehicle, and the road itself, like the music inside is cranked up loud. The van teeters right at the crest of the hill as if it’s about to spill down with wild abandon. And, doesn’t it appear that we’re looking at the back of the van? So, it’s driving on the wrong side of the street (at least in the United States). And those brake lights, barely visible, certainly don’t appear illuminated. Love.

If you’ll pardon one final comment (and a bit of wordplay), a cherry on top of this showcase is the wall dedicated to the legacy of Allan Stone. The Allan Stone Gallery opened in 1960 and quickly made a mark by taking bold risks with unknown artists, including women and artists of color, such as Robert Arneson, Eva Hesse, Joseph Cornell, and Oliver Lee Jackson. Stone was also notable for his early support of and deep engagement with key Abstract Expressionists, many of whom he showed, including Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline, and Arshile Gorky. He was a true visionary and iconoclast. Thankfully, he ignored Barnett Newman’s advice to “... get rid of the pie guy.”

The Unknown Thiebaud: Passionate Printmaker The visionary Partnership of Wayne Thiebaud + Allan Stone at the Sebastopol Center for the Arts from Jan 10th to March 8th, 2026. See SebAts.org for additional programming.