Kota Ezawa

Kota Ezawa (b. 1969 Cologne, Germany) visually transforms imagery he mines from the news, the history of art, photography, film, and popular culture in his acclaimed video animations, light boxes, murals, sculptures, watercolors, and other artworks. His process of translating primarily charged depictions from one visual form to another, is an inquiry, for the artist and viewer alike, into our cultural consciousness shaped by images.

Kota Ezawa’s artworks have been presented in solo exhibitions at the Baltimore Museum of Art, Baltimore, MD; Museum of Contemporary Art, Santa Barbara, CA; SITE Santa Fe, NM; Mead Art Museum, Amherst, MA; and Vancouver Art Gallery Offisite, Canada. Ezawa participated in the Whitney Biennial in 2019 and the Shanghai Biennale in 2004.

A recipient of a Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation Award, a SECA Art Award, and a Eureka Fellowship, Ezawa studied at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, the San Francisco Art Institute, and Stanford University.

The artist lives and works in Oakland, CA.

Kota Ezawa’s website.

The following are excerpts from Kota Ezawa’s interview.

Hugh Leeman: Kota, you studied with Nan Hoover and Nam June Paik at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf. How did that shape the way you think about time and movement and reduction, and what concept or principle from either of them still shows up in how you create today?

Kota Ezawa: These two professors, the way you studied in Germany at art school back then is really that you studied with one professor, very different from art school in the US, where you take a class with this professor here and this professor there. But in Germany, after your freshman year, you approach a professor and enter his, her or their class. And in my case, it was the class of Professor Nam June Paik. And he was at that time, very busy with his own career and had kind of a sidekick, New York performance artist Nan Hoover, who was much more present and very nurturing and also kind of, I don't know, instilled in me like kind of an idea that the United States might be an interesting place to take my next steps as a young artist.

You ask about movement and time. Those are such universal concepts. I feel most people think about them in one way or the other. I entered art school as a sculpture major and that was just what I was doing. But then video, which was really kind of new as a fine art medium at that time, offered a new, new kind of outlet for my thinking and for my making. And paradoxically, the first videos that I made were not moving. They were completely still. I thought that was like a genius idea. I didn't stick to it for the rest of my career, but, yeah. So movement and time developed over time, no pun intended.

HL: It's interesting to think this idea that you just mentioned, that you felt like it was a very genius idea of making this still video. At what point did that start to change for you, where you felt this sense of self and identity and confidence in it than you think? You know what, maybe it's time to move on. How did that inner dialogue happen?

KE: Yeah. So these still videos, I mean, every now and then I show them in an artist talk, but they haven't seen the haven't seen public eyes in I don't think since they were made. And it came out of, the nineties when I was in Dusseldorf was like one of the forces on artists was conceptualism. And I was, you know, infected. I thought about making very conceptual artwork, and I thought that was, you know, a concept to make something that a video that's not moving.

But then you asked about when that changed, and I can pinpoint it to the moment when I moved to San Francisco. So in nineteen ninety four, I applied for a year of study abroad, and on recommendation of Nan Hoover, I did this year of study abroad at the San Francisco Art Institute. And one of my first professors there was Nayland Blake, who a New York based artist, and he saw these very conceptual, text based, thinking heavy projects. And his advice to me was to stop being a smart ass. I'm very, I'm very grateful for that. I don't think you're thinking is, you know, part of making work, but it's not everything. And there's also, I don't know, your emotional investment in the work and what your body, how your body relates to what you do. So I'm very grateful for this advice I got.

HL: That's a very interesting thing to say, that you were very grateful for advice of someone telling you to stop being a smart ass at a bare minimum. The implication is, is that you were doing things that now you look back on and perhaps, are not so proud of. And I think many of us can say that in our younger years, what was the smart ass thing that this person was referring to?

KE: I think it was just kind of a I also got, you know, that's not the only conversation I had with Nayland. And I also got a lot of encouragement from them. And the stop being a smartass was just like one that landed very heavily with me. That's why I'm repeating it. But, repeat what you were just asking.

HL: I suppose in some ways it's if you kind of look back on who that Kota was at this time compared to now, what was it that you can look back on and see that how you were behaving, that you're like, God, I'm so glad that person gave me this recommendation to stop being a smart ass. What were you doing that he was referring to effectively about being a smart ass, so to speak?

KE: I think I kind of build a box around myself, you know, it has to be this, like exercise in being the smartest kid in the room. And Nayland broke that box for me, and that felt very freeing. But I'm not, you know, dismissive of the work that I did as a young person in Düsseldorf. I think it's also like, I feel after doing this very kind of conceptual, text based work, I veered extremely in the other direction and made very, like, heartfelt, personal work. And now the work that I do today, I would say is probably somewhere in the middle. There's, I feel very emotionally and personally invested in the work that I do, but I also think about it, and ideas are still kind of like the starting point of everything I do.

HL: It's interesting that you mentioned this kind of changing trajectory, not only of the work, but of yourself as a as a human, and that crediting this this teacher with breaking down that box that you've over the years, then had incredible names attached to what you're doing, the exhibitions you've. It's really impressive. The Shanghai Biennial, the SECA award winner from SFMoMA, the Whitney Biennial, Art Basel, the list goes on and on, not to mention major public art commissions. Amidst all of this, how has your relationship to visibility changed specifically? What feels different now in terms of perhaps pressure? Expectation? Freedom? Responsibility?

KE: I guess I have a little bit of experience now, but I, I must say, you know, like, I don't feel that you ever graduate as an artist. Like, there's no point where you say, like, okay, I got it down. I know how it rolls. Now I just have to open the tab and let out the let out the let the art come out. There's always uncertainty. These kind of engagements that I had with art world institutions that you mentioned, I'm super grateful for them, and I feel they helped also, you know, when you start out as an artist, people, the reaction you get from your parents and many others are like, yeah, right. You're you're an artist, you know? And then when you did go to art school and got your BFA or MFA or something, and then if you had a show at a museum and if your work is in a collection or if it's a work of you is on public display in a civic space, it kind of lends a stamp of legitimacy to what you're doing that I'm definitely grateful, but I still feel I'm making it up every day and I feel uncertain and nervous and excited about what I'm doing.

HL: What's the nervousness?

KE: I mean, I don't want this to be like a discussion about, like, what art is, but, like, one thing that art is, is it's, in my opinion, it's this kind of like walk on a on a very, very narrow path. You could also say it's like a dance on a razor's edge. And if you go towards one direction too far, you fall off. And if you go towards the other, it's a very delicate balance, I would say, when Art, you know, I make a lot of work and not everything I do is just completely brilliant and amazing. But I have done a few things where the effort that I invested in the artwork or video kind of incited an energy that leapt on to the viewer and like, you know, created some kind of amazing energy. And that is really what I'm after. And to create this energy through a work, through a video, through a print, through a three dimensional artwork is incredibly difficult. And that's the nervousness, like, how do I how can I fine tune my idea to generate this energy?

HL: Wow. Thank you. I appreciate you sharing so, so honestly on that. The the visualization you give of being on this razor's edge. And on one side you say you fall off. What happens on the other side of the razor's edge?

KE: You fall off as well.

HL: It's very perilous. So in researching your career, you know, in preparation for an interview, I came across an interview you did in two thousand and seven with SFMoMA, and there was a quote from it that I wanted to read to you and hear your thoughts in response to. You said, quote, I look at the history of photography not so much as a history of a medium, but as a kind of graphic novel and a kind of fiction of a history, end quote. It's a really interesting lens through which to see photography. For those who aren't familiar with your work, can you share more on the context of what this idea means to you now?

KE: Yeah. So this quote that you just recited is, is, you know, almost twenty years old. I'm still the same person, but I feel I'm a different version of the person that said that. But I can still kind of transport myself into the mindset that led me to say this. So the history of photography, like my engagement with the history of history of photography was quite random. Like I was an MFA student in the studio art program at Stanford, and I needed to two credits to graduate, and I was just looking at their offerings of summer classes and saw the history of photography. And I thought, like, that's probably doable for me. I'll just take that class and get my diploma and I'm out of here.

And the class was taught by Corey Keller, who for a long time also worked as a curator of photography at SFMoMA. She was a PhD student in art history at the same at that time. And, even though I had this kind of like, practical reason for wanting to take this class, I really got into it, and I got into it not because I had this like scholarly interest in photography, but because I thought the history of photography was so, it was like a crime slash war slash mental health slash. I mean, there's so much going on in the history of photography that's not purely art historical. There's the crime photography of Weegee. There's early, there's nineteenth century photography, which was like purely like a circus act. And then there's the writing of Susan Sontag, which I really dug, which thought of photography as an instrument of protest. And there's so many facets of it. And I thought it was I always look forward to that class and thought it was so entertaining. And that's maybe how why I likened it to a graphic novel. It was like a riveting story being told through images.

HL: I really like this idea. Riveting story told through images. You have this very interesting way of understanding, I think, the power of images. I want to come back to that later. But to build on this idea of the history of photography, there's a project that you engage with, the history of photography remix, and you speak of a leveling, iconic images and family snapshots into the same graphic language. How has that project changed the way that you think about the photographic history, which you were just referring to, and then which images specifically become canonical?

KE: Yeah, I mean, that project, the History of Photography Remix came straight out of this class, and I had an opportunity to do a small exhibition at the Santa Monica museum of Art, also in the early two thousand, maybe two thousand and four, two thousand and five. Shortly after I graduated from Stanford. And instead of showing a video, which was what I had done mostly until then, I wanted to show this slide show called the History of Photography Remix, which, I would say was really piggybacking on, on these ideas that you just mentioned.

And it started out as kind of taking the usual suspects of the history of photography. Weegee, who I mentioned, or Winogrand, August Sander, the early early twentieth century German photographer, and translating them into my visual language. But then I realized that that's again, kind of too small and narrow of a container. And I started including images that were just, like, lying around on my desk or that, images from the world of sports or that are not normally thought of as part of the history of photography, but definitely are part of the history of photography.

I mean, this one, the word iconic has been attached to my practice also for a long time, and I've always been, it's been a tiny bit uneasy with it, because I don't know that I really want to create like icons. Icons have a also a religious connotation, and that's not really what I'm after. But I do like when an image becomes accessible or recognizable and when it stirs an emotional response in the viewer. And that oftentimes happens when they when somebody encounters something in my work that they have encountered before like a memory.

HL: This idea of memory and reproduction. I want to talk about this because there's another project you did that connects art with history, with with memory and the power of Images. The Crime of Art project. It revisits the stolen artworks from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum and then other heist. And you put them in light boxes. How did working with these quote unquote missing artworks reshape your thinking about authorship and reproduction? And then I suppose we could even say the stealing back of these images.

KE: Yeah, the stealing back. I know also, you know, as an artist, just like as a athlete or I feel it goes for almost any profession. Now, you you're constantly asked to provide sound soundbites or statements. It starts with your artist statement as a as a art student. And then you know this stealing back, which I said prior to the release of this work, was probably the sound bite that I gave my gallery to put in the press release. And then it, you know, traveled on to the internet.

Yeah. Authorship is a tricky question. I'm it's something I don't. I like making the work that I do, but I never really think about the work being specifically about me. It's about the work. And I think some of the practitioners that have influenced me early were also hip hop artists. The early first wave of hip hop artists, people like Grandmaster Flash or Tribe Called Quest and they took samples of Lou Reed or Kraftwerk and remix them into new dance songs. And that's how I sometimes think about the work that I do. So rather than stealing back, maybe better thing is like sampling and remixing and giving things a new form. And there has been kind of like controversy about it, intellectual property, copyright, all of that. But I think it's so sad. I just listened to it's a what it's called it's a Hard Knock Life by Jay-Z in the car. And I think it's so good. And if anyone would have told Jay-Z not to remix this song from the Annie musical, it would have been a tragedy. Yeah.

HL: I want to go in on this a little bit more. There's an interview where you say, quote, I gravitate towards these almost overused images because I'm looking for some kind of community with the viewer, end quote, and that context. What does community mean to you in relationship to, say, mass media images that everyone's already seen so many times?

KE: I can also just go back in the history. It's not my personal invention. Artists have done this for decades and maybe much longer. If you think of Andy Warhol like who used photograph of Marilyn Monroe or of Popeye as a source or the Brillo, laundry detergent as the source material for his artwork. And it seemed kind of like, you know, it's the thing that everybody looks at all day long. Why would you not want to see that in an artwork? And, yeah, you know, art is such a huge field. I'm not saying that my way is the highway. I was never really interested in showing something really obscure and marginal and bringing it to the forefront that other artists are quite good at that, but that's not my forte. I think my I have, if I like it or not, some kind of a pop sensibility and I just have to go with it.

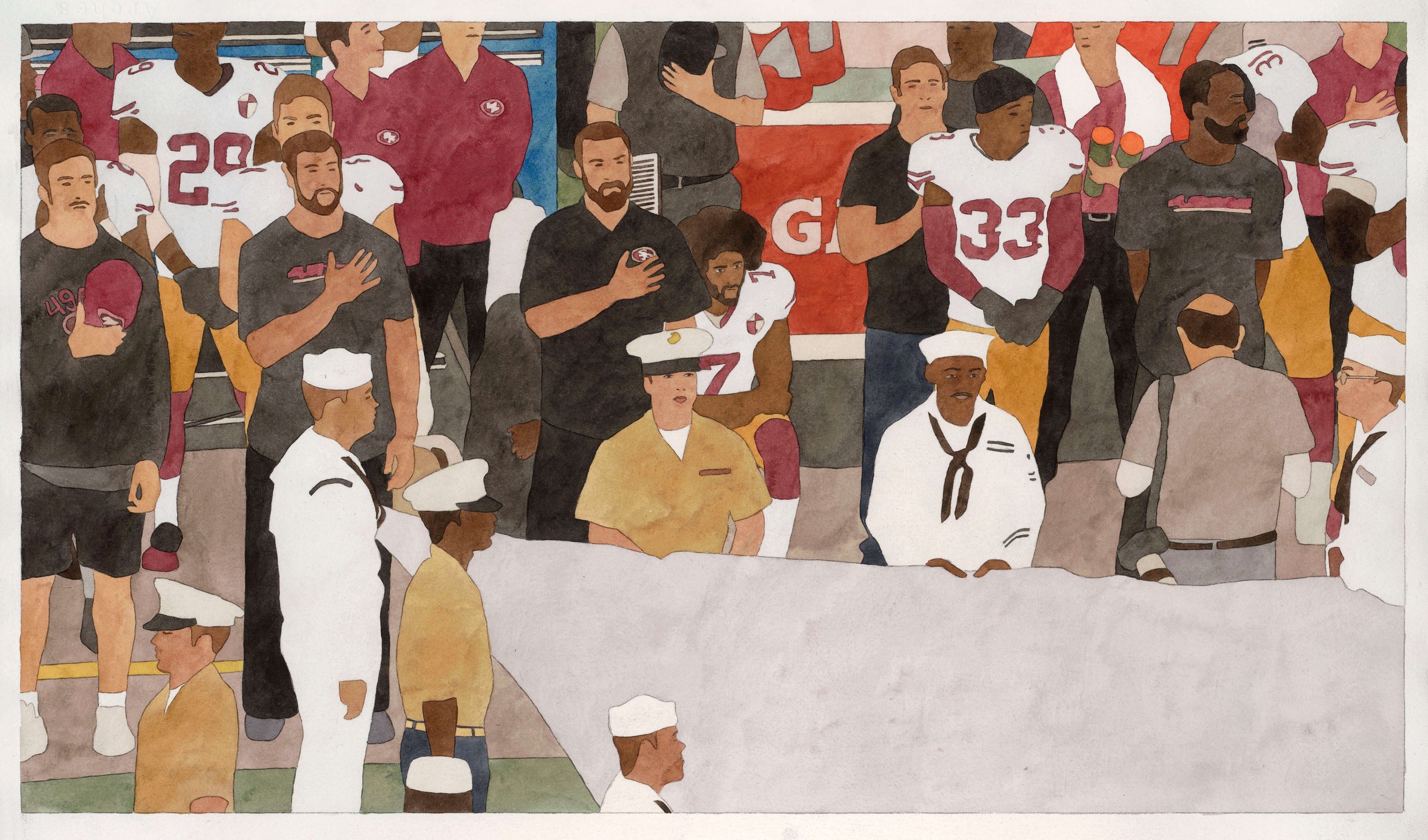

HL: These very well known images, you know, you've got the the Simpson Verdict, the History of Photography Remix that we've talked about the Crime of Art. I want to focus here a bit on the National Anthem, the piece that you showed recently at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. You translate NFL players taking a knee into watercolor animation. What are the medium of hand-painted frames allow you to say about protest and patriotism that, say the raw broadcast footage itself could not do?

KE: Yeah, it's a good question. When I make the work, I don't know. I can't say that I know what I'm saying. It's more kind of a hunch or an intuition that I go with. I even don't know what came first. The wish to make watercolor animation or the wish to work with these images. But very quickly, this, it was there was, for me, a clear connection between the two and I can't say what it says, but I can. Having lived with the work for a few years now, I can say that there was something that the watercolor did.

On the one hand, it kind of softened it visually. Like when you look at your phone or your laptop, there's kind of a harshness to the image and to the photographic image that the watercolor, just by using the medium of water and pigment, kind of softens. And then there's also this aspect of labor like this was not done using a watercolor filter in Photoshop or After Effects, but this was really like every color that's seen in watercolor animation was mixed. And then, you know, tested and applied to two paper and then photographed and animated. So and most of the work was done by myself. So it was also an exercise in labor. And I think this labor somehow connects to the subject because labor is time. Labor is kind of dedication. I didn't do this work as a publicity stunt or to land on the radar of someone. It was really something that I felt was worth spending fifteen months on. And that's also something that's expressed through the watercolor.

HL: You mentioned labor, and that's a really interesting aspect of it because the work that you do is very labor intensive. I know for some projects, you've even talked about hiring assistants to do things that could have been done much more efficiently, but you've purposely chosen this more analog approach to it. What is it that has kept you going? Because it seems like it could be very tempting to to do things in a more efficient way, so to speak, with using new technologies. What's kept you going with this?

KE: So also full disclosure, I have worked with assistants, and I even don't like this this work. Assistant one. Someone I work with, her name is Rhiannon Thayer. We've worked together for fifteen years, and I, Rhiannon was my student at CCA and then started working at the studio, and it's almost like like a game of ping pong that we play with images. And so I don't do every single brushstroke. And I work with an incredible studio here in Oakland, Magnolia Editions, and there are some like wonderful artists and artisans working at Magnolia. So it's there is an element of collaboration in my projects, for sure.

But I'm not like a movie director or film director where I'm just calling the shots I spent. I very purposefully take time every day to draw. And this kind of drawing exercise is almost like like going for a run or going for a swim. It just seems a kind of a necessary ingredient to what I do. I can't just it's not an intellectual exercise. It's also a physical exercise. It's living with the images. It's seeing the images very, very up close. There was a second part to what you asked, but I can't pull it up right now.

HL: I think, you know, you you've really touched on that. And I think the the thing that's really interesting about what you're saying is that there's this labor that you're putting into these things. And you really mentioned a beautiful idea here. That part of it is just the process of the labor, and you're finding appreciation in that, as opposed to saying we're trying to I think in the tech industry, you know, it's an idea of it's an efficiency of, of labor to get to a consistent product over and over and over. And art is not that and it really hasn't been. And I think that's what makes it meditative or whatever words we want to apply to it. And I think that's really what sounds like what I'm that's what I'm pulling from what you're saying.

KE: And then it's also, I mean, quite honestly, I've alluded before to the fine line that every artwork walks and I just have not found any automated, even though I work in a digital space, I draw on a computer with a stylus. I haven't found any automated press processes that can replace what I do with my hand and with my eye. The eye hand coordination thing is like is a necessary ingredient to what I do. It's not just about the colors and the shapes.

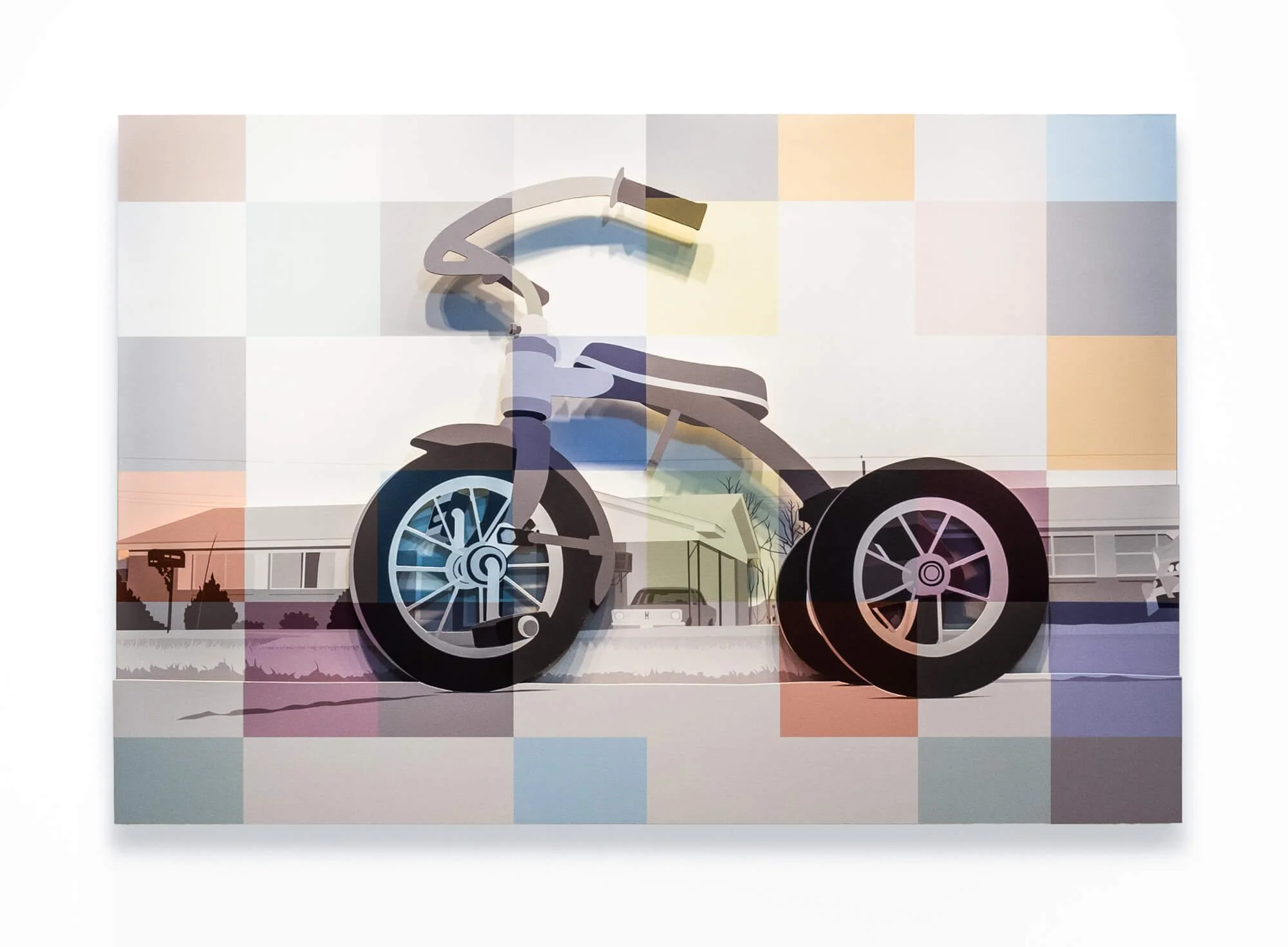

HL: I want to go back to something we said at the beginning, or we discussed at the beginning of the conversation about the expectation that, you know, as you go and show at different museums and the visibility of your work grows. And there's also these major public artworks that you're doing. I want to go to one specifically that takes place in Vancouver at the Vancouver Art Gallery, which is the museum there in the city of Vancouver. When you scaled up the size of the piece, Hand Vote, so that it could be put into a public street setting. What effect did that have on you conceptually and emotionally about the scene itself, about voting? How did that affect you?

KE: Yeah. Yeah. You mentioned this piece I did in the it started in two thousand and eight as a small scale sculpture, and then was reproduced in really large scale at the site that you mentioned, the Vancouver Art Gallery offsite, like an off site space of the museum. It was definitely a first. I didn't I was thrilled to have the opportunity, but I didn't really know. I couldn't imagine what the effect would be of seeing it in in this scale. So it was like eighteen foot foot tall sculpture and then maybe thirty feet wide and six feet deep, taking up like a good portion of a of like a public plaza in downtown Vancouver.

And it was weirdly, um, it's almost like when you have a kid or a pet, and then the pet grows and it comes like, and it's not really like it almost didn't feel like I made it. I mean, there were many. I worked with a team of fabricators, so, to one degree, it was not just made by me, but it was also made by this fabrication studio. But then it also felt like really external to myself. And, um, I say this, I talk about this with a friend often, like, it's really thrilling when an artwork develops a life of its own. And that's kind of what it felt like with this piece. I saw us tourists walking through Vancouver, downtown Vancouver, taking selfies in front of the sculpture. And that was definitely not an intention of the artwork. But like, it's a part of the life of the artwork that I totally welcome.

HL: I really like this idea of it taking on a mind of its own, because it speaks to the power of the imagination and the viewer seeing it, and they get to project some of their own internal landscape on it and interpret it in some ways. And it almost talks, I think speaks to this idea of a sort of common consciousness that people start to form their own opinions, and they influence other people's opinions about this image. And, you know, this is something I feel like is a main through line in your work. I want to focus on one last question here, to see if we can pull things a bit full circle with your career, your decades long practice here, and what might be the future of this. So you once said, quote, symbolic image content is in no way inferior to photographic image content. And in the same interview, you go on to mention that kids grow up watching these sorts of symbolic images that you're referring to as cartoons, and that we as children are able to read those so much more intuitively, clearly, from what you just said to even this quote here, you have a keen sense of power of images to shape perceptions of reality. So with that in mind, with all the technological changes today and a constant flood of imagery, not to mention your own kids, how are you thinking of the future of image's ability to impact art and perceptions?

KE: I mean, the our times are changing so quickly. I feel the world we live in today is so different than the world we lived in three months from today are, you know, so it's hard to say, like what the world will look like in ten years or fifteen years. But I guess my and my relationship to images is evolving. But for example, this like flood of images that you talk about that were exposed to, it doesn't make images irrelevant. It may be just changes, like what images rise to the surface and which images I pass by or like, don't care about.

And I feel like, you know, you can say we live in this image world that we didn't live in maybe a few decades ago. But then, on the other hand, Image World seems to have always been a part of, like, humans. What we do. Like cave paintings are images. Magic lanterns are images. Oil paintings are images. You know, they're this stream of images. It doesn't only go back with the invention of iPhones, it goes back way further.

HL: I want to ask one more question. I'm thinking back to what you said is such a powerful thing that you mentioned earlier, the the artists on the razor's edge. And if you go too far this way, it falls off and too far. The other way one falls off is when one falls off. What is that? That metaphor they fall off into. Into what?

KE: Yeah. I mean, it's just like, I think what I'm talking about is the making process, you know, you're a painter yourself. So I feel you had these moments where you just look. And this moment has been described in so many different ways by so many different people. Sometimes you do something. It can be a painting, a drawing, a video, a sound piece, and you look at it or you listen to it and you're just like, ding! You know, you, you hit some kind of mark for yourself. It's just for yourself. It doesn't mean that this piece will be enshrined in the Louvre or anything. It's just like for yourself, this piece hits something and it's just just like the most wonderful moment or feeling that you have as an artist.

And you live for that to replicate this moment over and over, and it's a constant effort. And then what happens after you have this moment is very like open ended. You know, it could be like five thousand people have the same experience that, you know, this it's basically an excitement that lives on this razor edge. And you want to create this excitement first for yourself, then for someone you care about and to other people. And then if more people can join this excitement, that's really thrilling. And to kind of and the unfortunately like this excitement is like fresh baked bread. It's good for like five days and then you have to work on your next excitement. Otherwise you know it, it gets stale. You can't just like repeat. So yeah, that's the dance we're doing. And it's in some ways it's exhausting because you're never done. You just always have to bake the next bread. But yeah, it's also what keeps it going and keeps it moving endlessly.

HL: Kota Ezawa, thank you so much. That's beautiful. It's inspiring to hear your thoughts.

KE: Yeah, I enjoyed it. And thanks so much for inviting me.