Cunning Folk: Witchcraft, Magic, and Occult Knowledge, Cantor Arts Center at Stanford University

By Alexandra Ellison

Black bands stretch and arch like bars, marking the surface of the page, registering its materiality while positing another reality. Image above language; one reads along the lines as they merge to construct picture and story simultaneously. The contours are elemental, curving to create bodies and landscapes. Shape, shade, shadow, chiaroscuro. Print is a principally monochromatic medium; the impression of space and imitation of reality achieved through gradations of black and white.

At Stanford’s Cantor Arts Center, a spotlight exhibition entitled Cunning Folk mobilizes a small but carefully selected group of prints from the museum’s permanent collection as the starting point for a single-room show dedicated to depictions of magic in the early modern world. The exhibit explores the idea that to be cunning was to occupy “a broad and varied realm of secret knowledge,” elaborating the complex conceptions and representations of divine and demonic power that were prevalent in Europe and its colonies during this tumultuous period (c. 1450-1780).

Although prints form its foundation, the exhibition is accentuated by an assortment of objects ranging from medieval amulets and early modern books to contemporary sculpture. Taken all together, it seems and one senses – hearing the deceptively dulcet tones of folksong echo through the gallery and spying a life-size cast of a naked female body riding a broom – that this is a show about witches or the popular perceptions, common portrayals, and even practical evidence of witchcraft across Europe (and eventually America) over the last six hundred years. Divided into the sections Sabbath, Spell, Stranger, and Suspicion, this presentation reveals how, in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, artists (as well as writers) from Germany, Italy, Spain, France, and North America were united by a “visual vocabulary of witches,” characterized by themes of sexuality, secrecy, and superstition.

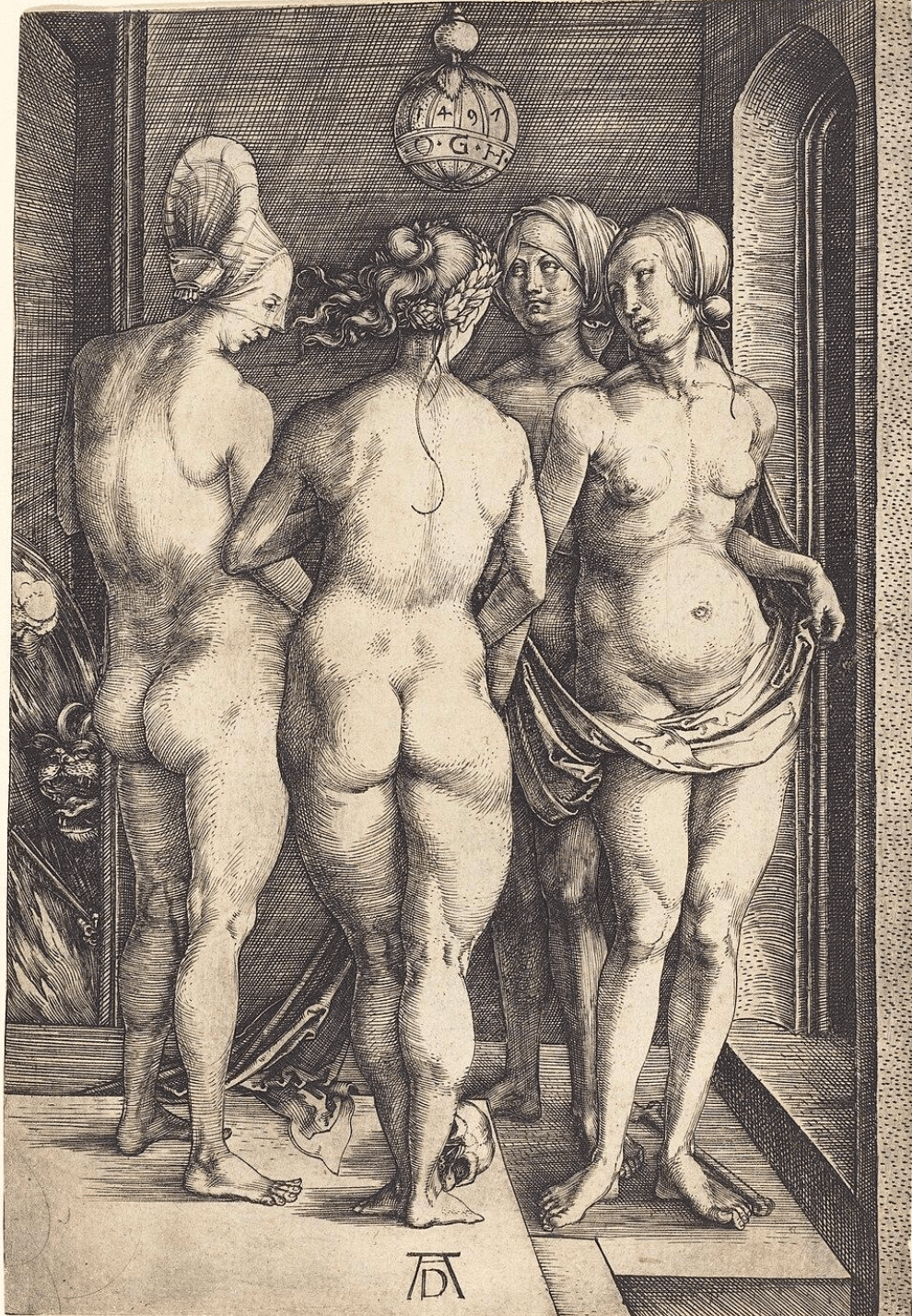

Repeatedly, we see twisting trees, curvaceous bodies, long hair, women gathered together, nocturnal scenes in nature or by the hearth, the depicted figures’ closeness inherent, wisdom evident, and power made apparent amidst the chaos. The communal and elemental are everywhere throughout the exhibition. In particularly strange and enchanting chiaroscuro renderings by Albrecht Durer, Jacques Callot, and Francisco Goya, that sense of atmosphere and tension is pervasive. This style complements the fundamental concept of contrast on view – light versus dark, good versus evil, learned versus local, male versus female, us versus other.

Chiaroscuro, in its original Italian, literally means light-dark. It encompasses dual forces, positive and negative, presence and absence. It is an artistic technique that imbues an image with visual depth and, at the same time, an enigmatic and mysterious air. The word aptly describes many of the pictures on display in Cunning Folk, but it is also well poised to take up the paradoxical (or rather, heterodox) ideologies on display.

Hans Baldung (Hans Baldung Grien) (German, 1484-1545), The Witches' Sabbath, 1510. Chiaroscuro woodcut, printed in black and gray-green inks. Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco, Achenbach Foundation for Graphic Arts Art Trust Fund, Ludwig A. Emge Fund, and Gift of Ruth Haas Lilienthal. 1984.1.111

Directly adjacent to the gallery’s main wall, text explaining how the exhibition takes the term cunning from English clergyman and philosopher Joseph Glanvill’s pivotal treatise on witchcraft from 1681, one encounters Hans Balding Grien’s dense and provocative image of five witches making their sabbath in the murky night. Their nude, voluptuous bodies are busy performing profane acts out of doors, in a landscape cluttered with bones. Grein expertly employs a relatively new practice in printmaking: the chiaroscuro woodcut. The technique developed in Germany and Italy in the early sixteenth century allowed artists to achieve a greater sense of form and depth in a composition by using multiple woodblocks to print and layer different inks. In the scene, as one of the women lifts the lid on a mysterious vessel inscribed in a cryptic, pseudo-Hebraic language, a torrent of smoke or perhaps water (some kind of substance) erupts outwards, gleaming with shards of stone, flecks of white, and even a small frog. We observe dark and light, and something emerges in between. The imagery is disturbing, yet there is pleasure in the discovery; in letting the gaze flow along the lines that shape locks of long hair and seeing that same line echoed in the bending branches of the nearby tree, the shag of the flying goat’s fur.

Among the depictions of ambiguous and arcane rituals performed by women participating in the devil’s sabbath, we encounter an especially grotesque witch, mounted on a cage-like carcass, riding through the tall grass in another lush landscape. Once again, the witch is old and naked. Agostino Musi portrays her hands clutching at a brood of babies while she sticks out her wicked tongue and lets her long hair fly loosely. Her grim chariot and quick chase are made possible, somewhat perversely, by an assembly of young men. Their strong, supple, and equally naked bodies pull the scene forward, giving it pace. A similar sense of motion and dynamism is observed nearby in Jan van de Velde II’s The Sorceress (1626), an engraving which takes this subject to its strange zenith. A younger, although equally long-haired and scantily clad witch waves her hands above a cauldron, accompanied by a rabble of strange creatures, who smoke and crackle with energy in an image that glitters with the same kind of alchemical magic it endeavors to represent.

Informative wall text and panels cover impressive ideological ground, providing succinct explanations for each artwork, object, and treatise on display. The exhibition effectively conveys the complex and multifaceted beliefs about witches and wise folk as these ideas continued to evolve and disseminate during Europe’s era of exploration and encounter, leading up to the Enlightenment. For it was in the so-called “New World,” in the English colonial settlement of Salem, Massachusetts, that perhaps the most famous persecution of witches took place.

What strikes a chord is that most of these threatening, suggestive, and transgressive portrayals of cunning folk consist of women. Of the nineteen unfortunate souls executed at Salem, fourteen were women. During the early modern period, tens of thousands of people were accused of witchcraft. Women were disproportionately victimized, with contemporary estimates placing the number of female executions in Europe and North America between 30,000 and 50,000. Non-Christians and foreigners, the ultimate “others,” were also frequent targets in witch hunting. Giovanni Battista Tiepolo’s eighteenth-century etching of an elderly turbaned Turk, with his fateful finger pointing at a decapitated head, underscores the ways in which fear is strengthened through and by difference. During the Age of Discovery, the heretical power of magic and witchcraft became increasingly viewed as both an internal and external existential threat.

The imaginative artwork and unusual objects on display at the Cantor invite us to open our minds to alternative theories about the mysterious potential of certain “cunning folk” to transform the natural world around them. As these different narratives unwind around the gallery space and the notions of cunning and wisdom give way to witchcraft, one may begin to wonder why? From Madea, engraved with her caduceus, to the peasant woman drawn with her distaff, why is it that women were predominantly, not just depicted, but accused, convicted, and punished as witches?

(L) Louis Desplaces (French, 1682–1739), Jason and Medea, c. 1720. Etching and engraving. Cantor Arts Center, Stanford University. Robert E. and Mary B. P. Gross Fund, 2007.15

(R) Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo (Italian, 1727–1804), Woman with Distaff and Sleeping Figure, 18th century. Pen and wash in brown ink over black chalk. Cantor Arts Center, Stanford University. Gift of Mortimer C. Leventritt, 1941.279

Silvia Federici’s book Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body, and Primitive Accumulation (2004) provides a clearly defined conceptual bridge between fear of the female and fear of the other, as well as a fruitful framework for beginning to understand what seems so shocking to us in retrospect – the intensive witch hunts which took place during the same period the exhibition spans. Frederici’s main argument considers the alienation of the peasantry from the land as well as the dramatic change in work and societal conditions as communities shifted from feudalism to the wage-based economies of capitalism. The prints exhibited in Cunning Folk elucidate the association between witches and untamed nature, emphasizing their powerful relationship with the land and its animals, their supposed ability to influence and harness the elements, and, thus, to metamorphize reality. Magic may have been something as simple (or sinful) as contraception.

The large seventeenth-century herbal on display alludes to what is now generally accepted, that in some cases, witches were women who had specialised, remedial knowledge. In the medieval and early modern world, women acted as midwives and healers, but as science and medicine began to coalesce in the centuries leading to the Enlightenment, women became increasingly unauthorized to participate in such practices. In Caliban and the Witch, Frederici argues that unique cunning women within communities became regarded as subversive, and their practical magic (valued remedial knowledge, domestic labor, and reproductive abilities) seditious. The female body was thus destined and designated for control, discipline, and punishment under capitalism. Taking these concepts further, the body of the colonized person is, unsurprisingly, subject to the same and even more extreme subjugation (slavery).

It is natural that we are captivated by what we don’t understand. This show, in its celebration of different ideas and embodiments of magic, occult rites and rituals, presents audiences with works of art that open up space for important discourse about what caused this intense fascination with and fear of witches across different cultures just as the rise of science and a Cartesian, mechanistic view of the universe was beginning to “disenchant” the world.