Abby Chen

Abby Chen is Head of Contemporary Art and Curator at the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco. Since joining in 2019, she has led the museum’s Transformation project, commissioning large-scale works by Asian American women artists and acquiring major collections, including the largest holding of Bernice Bing. Previously, she worked in the Chinese Culture Center of San Francisco in Chinatown for over a decade on creative placekeeping.

She also founded the museum’s Practice Institute, a think tank and digital laboratory for reimagining museum practice through innovation and global collaboration with artists and communities.

In 2024, Chen curated Yuan Goang-Ming: Everyday War for the Taiwan Pavilion at the 60th Venice Biennale and co-curated the American Pavilion at the Gwangju Biennale. Recipient of the 2024 National Art Education Association Distinguished Art Educator Award, her curatorial approach explores intersections of race, gender, sexuality, migration, and technology, advancing new narratives of contemporary Asian art worldwide.

The following are excerpts from Abby Chen’s interview.

Hugh Leeman: Abby, you have an interesting backstory on your path to becoming an art museum curator. You were working at a corporate finance job and felt a deep sense of emotional disconnect with your colleagues and a sense of social distance in personal values, which set in motion a major life change. Can you tell the story of that change amidst heavy family expectations, and what was your inner dialogue like as you traded the more esteemed financial stability in the finance world for that of the arts?

Abby Chen: I think at the time in the corporate world, at a lot of levels, we got along very well. Because if you're not getting along very well, you don't have the desire to share more. But because we got along so well, you started to feel the gap. There's so much more you want to share, but there was no bridge, no avenue. I think that was one of the starting points.

Also, I was actually quite empowered by the American corporate environment at the time. I mean, later on, I started to see the other side, but at the beginning, this very motivational new way of building culture within corporations was something very new to me. I think if there's anything that corporate America should be praised for, I think that should be given credit. But because of that, it helped me to really think about where I want to position myself, how I'm positioned in society.

Also, that finance world was very different from any other place because it was working with all these stealth mode companies. You'd see these people coming in with their dreams, just thinking about all these impossibles, and that's very close to art actually. I think that was a big part that made you feel like, oh, I could do it too. Also, I was at a point where I felt like I just had to do this, and it wasn't strategic. I had no idea. I'd never quit a job before. I'd never resigned before. I didn't even know what it felt like. But the creative side, the art side just continued to pull me and I couldn't resist it. That's how I made the change. I think I left around 2002, and it wasn't until 2006 when I joined the Chinese Culture Center that it finally started to feel like this is a more solid direction that I'm moving towards.

HL: When you were at the Chinese Cultural Center, under your direction it was often described as process-driven rather than product-driven. What does that mean?

AC: I think very soon after I joined the Chinese Culture Center, I realized there was a preset way of doing things. There's a preset community expectation. When I joined, I never went through that kind of process, and if I followed that process, I knew I was going to come out with an outcome that is not me, that is not what I see the future should be.

Also at the time, the way the community expectation was, I think there was a lot of desire for change but no one could really articulate it. Everybody knew this isn't working, but no one could really articulate what that change should look like. I didn't either. But I knew it needed to be different.

I think there are certain culture workers or curators who will know exactly what that looks like and just get that out. For me, I felt like, what if we change the way we do things and let that lead us? That's how more and more it became a very formative sort of journey that allowed me to learn from the process. You really dig deep working with an artist. You conceptualize with them together. You work with the space. You try to understand the community, the environment, the city together. And then you think about what, after you're mapping out all of these parameters, what is the path to navigate all of that and then get the outcome that we wanted.

Also, I felt like having worked in corporations before, I was well trained in logistical planning and thinking. Also, by leaving a very comfortable job and doing all kinds of odd jobs and trying to do my small business and all of that together, it taught me a lot about money and budget. So I was able to work within our means while also trying to figure out additional revenue sources.

I remember one of the things was that Chinese Culture Center was actually one of these organizations that very early on had a website, I mean, talking about when the internet was just starting. At the time, the board and staff had a very rudimentary HTML kind of website, but because of when it was built, it actually accumulated a lot of credibility. Certain areas, particularly the site on Chinese Culture Center, had a lot of visits. I don't think I've told anybody about this before, but Google was just rolling out AdSense and we found a new revenue stream. I remember we got at least a few thousand dollars a month by putting Google AdSense in there. So that was an incredible revenue source. I mean, of course they're looking at a nonprofit, I forgot, was it $30,000 or $50,000? It's not a whole lot in the annual budget, but at the time the bookkeeper was saying, "Oh, it's peanuts," but no, it's actually not peanuts. It's actually a lot of money when you have this kind of passive income, when you don't need to fundraise, when you don't have other revenue streams. This is actually very good income.

So I was able to find money here and there, and we started to reapply for grants and all of that after being dormant for a few years because of the renovation. So the whole process was very different, and particularly on the art side, we turned so much more to co-production, co-creative, than the final product, like just receiving the artwork, hang it, that's it. But we were really thinking strategically on branding and thinking about how Chinese Culture Center could build a very unique sort of program and stand out in the country.

I remember I looked at the landscape of Chinese cultural institutions in the country. I mean, there are a few. Actually, the first museum show I did was before joining Chinese Culture Center. It was with Museum of Chinese in America, MOCA in New York, and I was doing a photography show there. So when you look at these cultural institutions with the immigrant identity, you can call them identity-based institutions, they all share a lot of burden, and what they could provide to the living artist was very limited because the organization is trying very hard just to survive.

So in a way, I think I saw a huge potential for creating and inventing some very innovative programs. That's how we created the Shenray, which means fresh and sharp. I remember when I was thinking about that title, because in Chinese there are a lot of people who will use a similar word, but they call it xīnruì, which is new and sharp. But I thought, they don't need to be new, they actually need to be fresh. So that's how the fresh sharp idea came about, and also they share the same sound. One is the last two words and the other is the first two words, so Fresh Sharp just became a branding identity within CCC.

Good that we came up with this to support mid-career artists to launch, giving them a springboard, a platform to launch to a new phase. But then after the first one we did in 2008, I mean, now it's 17 years later, it remains the only, still remains the only program in the country. I mean, what the hell?

So at least with this Fresh Sharp series, you're highlighting solo artists. You want to give a boost to their career, and you really want to look at what the migrating experience had as an impact on their creativity. Some of them were first generation, but more and more later we started to work with second generation and beyond. And even sometimes there are artists that don't even speak Chinese, but it was important that their strong connection with Chinese in this country and Chinatown gave us a new dimension to this contour on what we think the art coming out of Chinatown should look like.

Also, I remember when I was in school, when I was in art school, I was reading Homi Bhabha's "The Location of Culture." It was one of the hardest books I read at the beginning, but later on I found myself constantly referring back to the so-called location of culture, the locality of it, because this is happening in the center of where the migrating experience is. You have the high and low. You have the rich and poor. And even geographically, 750 Kearny sits right at this street that divides migration and also divides rich and poor, the Financial District and Chinatown. And then of course another irony is that you can't really just find it. You have to get into a hotel to locate it.

So the location of this culture that came within that started to burst this energy, and it had to be largely driven by process. It cannot be driven by product or outcome, and it's only that process that will guide the outcome. More and more we realized it was actually not the outcome, it's the process that will make that difference.

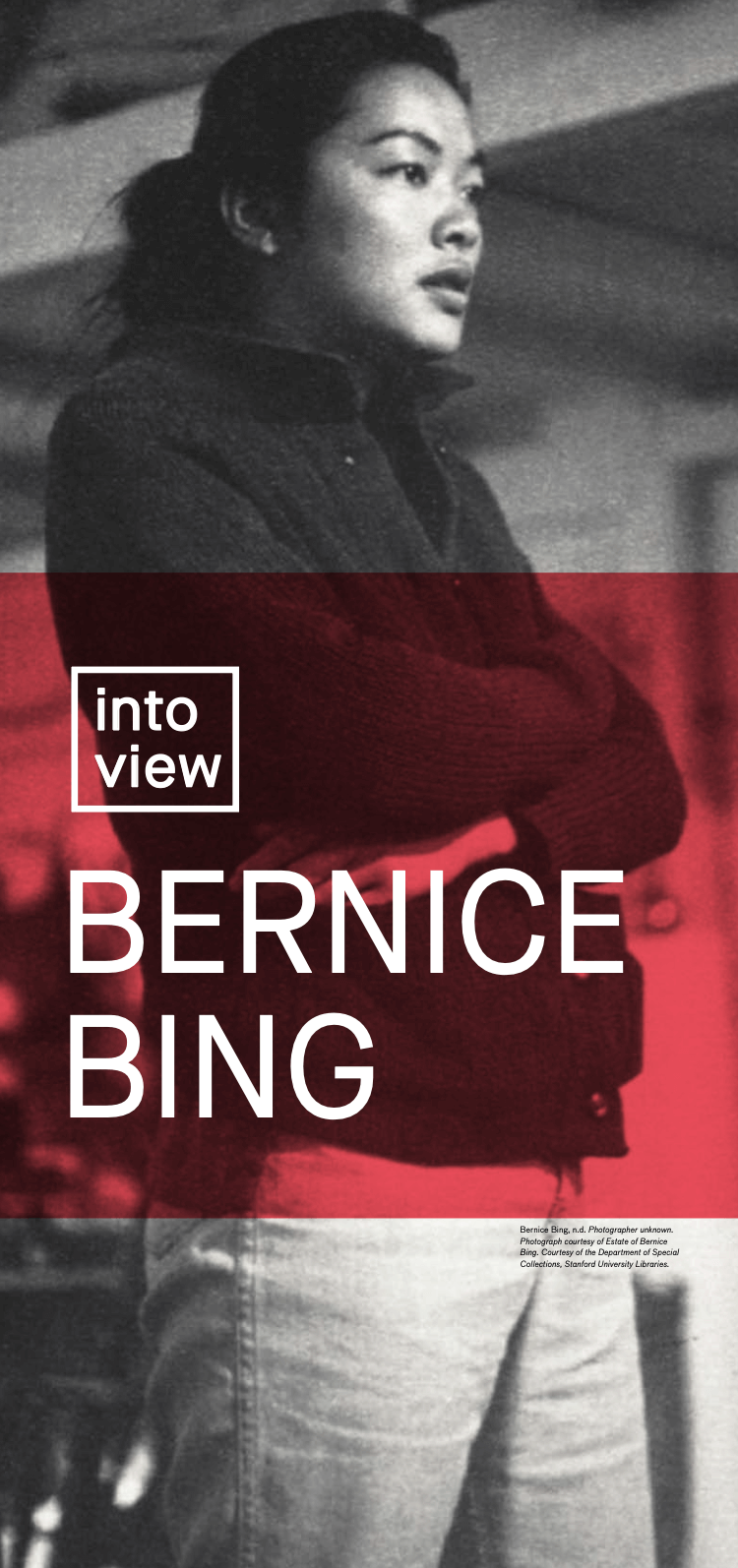

HL: That's fascinating, especially this idea where we talk about the division line at 750 Kearny. I want to segue into your time going from the Chinese Cultural Center towards more recently the Asian Art Museum with "In View with Bernice Bing," where you helped reposition Bing from this marginal figure to a central reference in Bay Area art history. When you think about how the show you curated impacted museum collecting priorities, what could be repeated by other curators to do the same for artists that have long been at the fringe?

AC: Oh, that's such a good but complex question. I think about this question a lot. I think about the history, what makes a city or region, what gives character to a region a lot. What makes us feel attached to a place? And so when I think about that, I think about what is city building? What is history building?

I think for a very long time we've been talking about how history should not be written by the so-called winners. But in terms of writing, rewriting that history, we still need to look at what we turn to, which is some of the most concrete, detailed people and the kind of micro actions that they do.

With Bernice Bing, definitely I think there's luck involved, but more importantly I think this strong sense of, you need to follow what's happening and you also need to unfollow. In Bing I see a lot of myself because she was at the beginning Western art trained, and she basically had to untrain herself, the so-called unlearning and relearning or create new learning, because there's no model to follow. So I see myself doing a lot of that. You need to follow what is happening, what's trending, but then on the other hand you also need to tell yourself to unfollow. You need to unfollow all of these trends that could be misleading and noises, whatever that is just trying to program you.

And then, and I think we talked about this at that AI conversation as well, you need to detect what you also need to follow. Actually, it wasn't until I came into Asian Art Museum I realized how few Asian American artists were collected, because in my knowledge building up to the moment to Asian Art Museum, I thought that these artists, really critical artists like Bernice Bing, Carlos Villa, I thought they were probably collected in places already. Maybe not as many as Warhol or Judd, but they should at least be collected by quite a few. To my great surprise, it's actually not.

And of course, Asian Art Museum has its own burden and background because for a very long time the museum was positioned only to collect artwork from Asia. So that prevented them from collecting local artists or American artists with this very strong Asian tie or migrating history. But this was my following and unfollow experience.

When you say can that be modeled by elsewhere or others, absolutely, especially now. I feel there's so much we need to unfollow, and we need to develop some kind of a new follow. We can't just think about, oh, is it going to be a trend? If you want to set some sort of trend, I think that's very dangerous because you're actually aiming for something else.

It will be critical as we unfollow certain kinds of patterns that we need to also be very clear that we are treading into a lot of unknown territory that we just need to live with some of the uncertainty and unknown. And in so many ways, Bernice Bing or Carlos Villa, they're not unknown at all, so it's already a lot easier for us to follow them. And then I think it's just about, okay, you know that you want to follow this and how do you negotiate to carve out that path or to carve out the resources to do the following?

I remember very clearly the conversation at the time I had with the estate. She was telling me that there were other institutions that were interested, but they just only wanted the gift, and she was like, something was not right about that. And I was like, I agree. I said, with institutions collecting the work, I feel like for Bing, we should pay to get her work. And that was what we did. We paid for "Lady and the Road Map" as well as the really major work that she made called "Epilogue." I mean, it was very intentional. She actually named it "Epilogue," like a way of closure or saying goodbye. So those two significant works we made the purchase.

And then of course the estate was very generous and gifted us quite a few works, including one which I thought is the most significant, that's her self-portrait. And very thankfully, because of the impact "In View" was able to make, then we got phone calls or contacts from others, like her friends contacting us and willing to give us access to her other work, and we were very lucky to get the portraits that she did in the 1970s with a trip that she made to Smithsonian. She saw this Dutch painter's portrait, I think it's called "Portrait of a Lady" or something. And she saw that and she was just like, I really love the way that this was painted, and I was thinking, why can't I make a portrait of all ladies? And so then she basically used the same structure and started to apply all different kinds of ethnicity to that portrait, which was something, I mean, I thought that in the 1970s she already thought about doing this kind of reverse appropriation was just so incredibly intelligent and thoughtful.

I'm thinking about writing actually, writing an essay about it, from her self-portrait that she did in the '60s to the '70s when she started to make portraits for the people. So from appropriating herself to this idea of applying that to everyone else, like democratizing this language. So I just thought that was so beautiful. It takes a very strong mind, a very intelligent strong mind to figure out how to do it in a tasteful way.

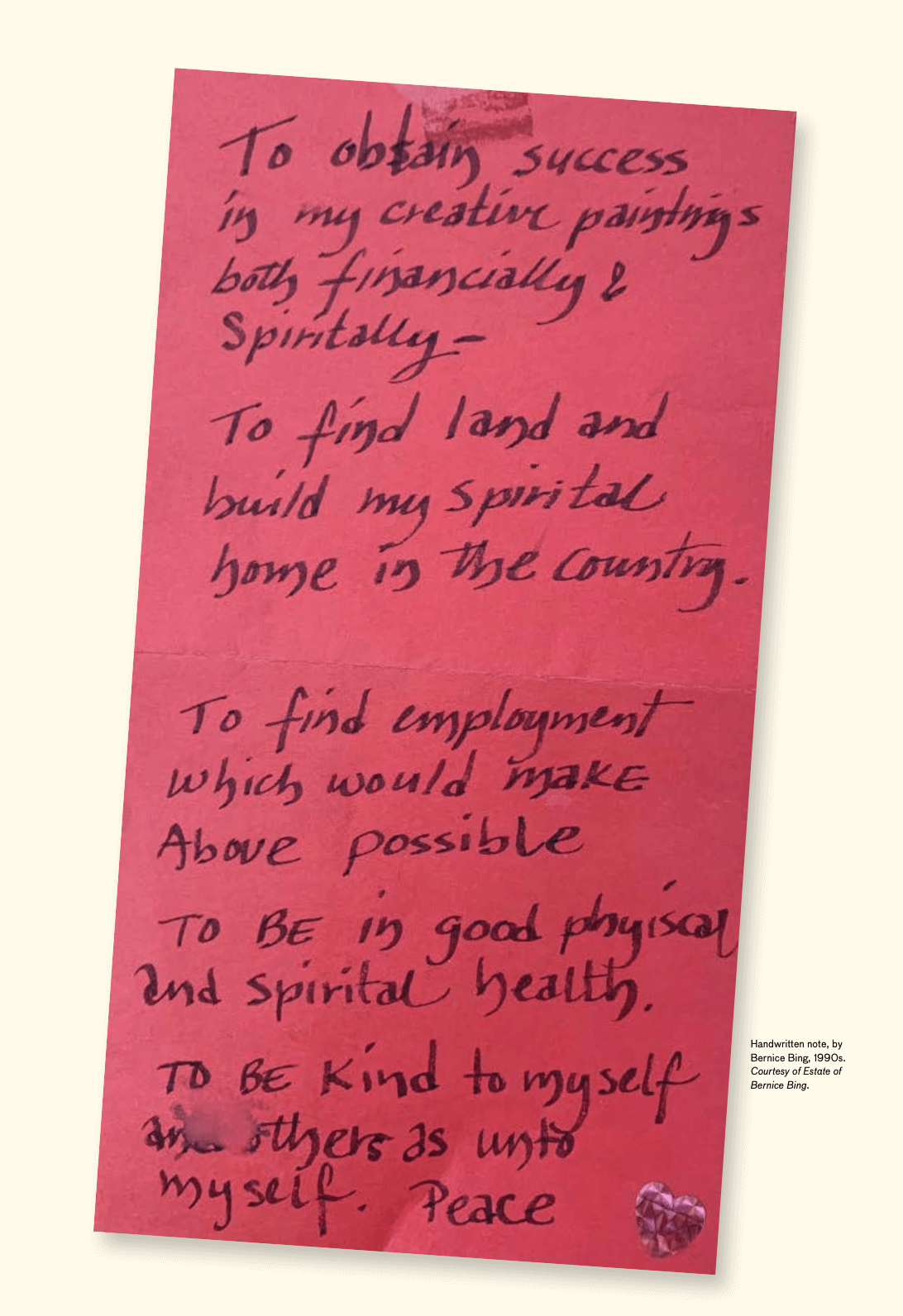

I just feel like I continue to learn and absorb the energy that illuminated from Bernice Bing. Because she was at a time I think is equally volatile as now. And one of the things I showed in "In View" was her handwritten poem that she copied from a poet she really loved, and the title was "In the Dark Times." Yeah. So a lot of those, and I feel really lucky that she was documenting her thoughts, probably for herself, because she was quite alone even though she had a lot of friends when she was thinking about these deep ideas.

HL: I want to switch from Bing to something much more recent. So earlier this year, you opened "Everyday War" in San Francisco at the Asian Art Museum after curating Yuan Goang-Ming's exhibit at the Venice Biennale. For those who have no context on this, can you talk about his exhibition, its geopolitical implications, and then the potential vulnerabilities of the artist in putting this work forward?

AC: So I feel really honored and privileged that I got invited to curate "Everyday War," which is Yuan Goang-Ming's solo show representing Taiwan at the Venice Biennale. I knew about his work for many years, but the one that really struck me was actually one I just saw accidentally when I was in Japan in their new acquisition show at the Mori Museum. That was "561 Hours of Occupation."

I mean, from a critical standpoint or even from himself, he is always looking for poetry in life despite the environment, and he always looks for the poetic. But that was really, I mean, beautifully shot for a very intense moment in Taiwan's history as the young people, the younger generation, was taking the lead to occupy the legislative hall of Taiwan. The way that he was shooting it, I feel like it really makes it very holy in real time, but almost like both a church, a shelter, and a place of triumph and celebration.

And that is a moment I was deeply moved, because thinking about me as a teenager in 1989 and seeing how the young people were trying to have a voice in Hong Kong, and then at the time, because I saw this in 2019 where the actual event that took place in Taiwan was 2014, you all of a sudden in this nonlinear moment, but all of the memory kind of all collides into one. So I was very touched by that.

And then we worked together on "After Hope." So that was one of the 52 videos in "After Hope." And then later on I got invited to do this, and I got the opportunity to look at all the previous work in a very detailed way. And at the time I knew that he was working on this work called "Everyday War." And I had not seen it, but he described it. He had a script and he described, and I thought it was, at the time it felt a lot like a dwelling, but it was very hard for me to imagine how they're going to be different from each other, especially since he has done so many explosives.

And then he also told me that he wants to do this flat world, but the exhibition title is going to be "Everyday War." There was no discussion about that. It was just like, it's going to be "Everyday War," that's it.

But one of the most critical discussions we had at early beginning is when I saw the artwork list that he proposed. The "561 Hours of Occupation" was not part of the artwork list. And because I had such a strong connection with the work, I did ask him, what is the reason that that work was not in if you actually want to talk about this everyday war as an artist born and lived in Taiwan?

And he was like, "Oh, that work might be too political and this whole exhibition has got nothing to do with politics. It's actually really about me myself, how I live through the everyday war. And the everyday war for me is about this pandemic, cyber attack, disinformation, climate change. This is the war I'm talking about." So I felt like that work was not relevant in this context.

And I said, I need to respectfully disagree as a curator. Of course, as an artist, you will make the final decision, but I feel like with all the works, everything else in this show, there's also your aesthetic and your choice. There's actually no real human being in all of these other works. So you're showing, you're representing Taiwan in Venice. And I'm sure probably in any recent decades of Venice Biennale, there's not going to be a shortage of commentary on war or conflict. This is where at the world stage people want to bring all of this topic forward.

And I found it really critical that when you show a lot of these kinds of chaos, problem, anxiety, at the same time, you do have, if you don't have that kind of work, okay, but you do have a work that actually demonstrates action that leads to hope amongst all these unthinkables. And I feel like in order to make this show holistic, you need to allow people to have an outlet to actually, among this, be able not only to connect with the chaos and the anxiety, the fear, but also connect to what everybody can do, can take action and can have hope. And I think that is really the strength of "Everyday War."

And he said he was actually immediately convinced and decided to put that work in. And so that goes hand in hand with "Everyday Maneuver," which is again an actual air strike drill in Taiwan that takes place every year. It's a top-down approach from the government, from the authority trying to keep their people safe. And it's a mandate, right? It's massive. It's very macro because it's not just Taipei City, it's a whole island, including the offshore islands.

And then you'll have something that is very micro, that is very individual-based, even though it's a mass event that took place, and it was a bottom-up approach. And one is very external and one is very internal. So I think those two mirror each other is really important for the people that come to Venice to understand what he's trying to say and what he's living through. Both what's happening inside of his mind and also what's happening in the real environment.

HL: I want to dig in on that idea of what was happening inside his mind, then even with you personally on that show. So Yuan Goang-Ming's family story is entwined with the Chinese civil war and unresolved displacement between mainland China and Taiwan. When you were curating this, first in Venice, then here in San Francisco at the Asian Art Museum, how did your own Chinese heritage and your feelings about the China-Taiwan relationship enter into your thoughts?

AC: Well, I'm such an odd choice. Actually, I'm probably the first one ever that was born in mainland and also as an American and got invited to curate this show. So you think about this tension of the strait, I in a way sort of embody the two big forces, or even if I personally don't think so, I reject that idea, but then still, I mean in the optic that was the forces that are trying to influence Taiwan.

But then on the other hand, I also feel very fortunate that I'm the curator to do that because for me I hope is not just an exhibition about Taiwan itself. It is an exhibition about a narrative that spans close to a hundred years. Multiple generations living under, through, and away from the fear, the trauma of the war. And when Yuan Goang-Ming was growing up, watching his dad and his dad's same generation watching a Chinese opera about the inability to return to homeland and just all crying in a theater and not quite understanding it but remembering it. By the time from a son he became a father, and this tension of war has never been this close for him and his family. And looking at his children, looking at his own daughter, and he's constantly navigating between the trauma that accompanied his upbringing and the unknown and the uncertainty that is hovering now over himself and the younger ones.

So I think for me as a curator, something very important about this show is to communicate that narrative. I actually wish more Chinese or mainland Chinese can see the exhibition so that we can create some shared reality, understanding, and really very precious but not easy shared empathy. Because I feel like, I mean, in this world of information we really don't have a shared reality. When we don't have a shared reality, there's no way we can have a shared empathy. Probably the only thing that you could share is hatred. And that's really sad, right?

So I would say that was what my ultimate goal is. I don't know if it's an ultimate goal, but I would say one of the goals is to at least carve out a space to allow a peek into someone's mind by really living in that condition. And there's no other way. I don't know how many news reports that people can see these days can really allow that to happen. The only channel for me is through art.

And particularly as people sitting down, and so the chair setting was very important for me when I was thinking about the show with Yuan Goang-Ming, both in Venice and here in Asian Art Museum. This is probably the exhibition that has the most chairs or sofas, actually, sofas to be more exact, because I was very adamant that it needs to have a backing. People really need to feel very comfortable sitting in there. And that for me is a physical sanctuary that we could provide among this chaos. That is a place that you can sit comfortably. If you want to look at your cell phone, you want to take a nap, you want to talk to people, all of that is fine. And as they look at the screen, whatever that they're feeling inside, it might not be the war on Taiwan, but it could be the war on the climate, the war on our public policy, disinformation, cyber attack, or your email, you got a phishing email. I mean, all of these things. But there's a moment you can sit there comfortably, and that part becomes actually something very important in this holistic experience.

HL: With your connection to curation and the work that you've dedicated to this sensitive topic in mainland China, how does your connection to it affect your relationship with mainland China, the potential of the government, the idea of the information war that you're referring to, and what might your concerns be around that?

AC: I actually didn't really have that many concerns. Again, I look at the process, the process of how we curate it, what's the curatorial intention, what is the artistic intention. I think the intention is really trying to show what's happening in somebody's mind, what he's going through, what his family history that led to this moment. So I think to foster some sort of understanding in the current state of mind at this moment is important because "Everyday War" was created right in 2024. I mean, literally a few days before the exhibition happening, as the exhibition opening, so it's very current. And in a way it's one of these spaces that could offer some sort of authenticity.

And so for any mainland people to come in to see this, yeah, the geography is one thing, but more importantly, is there a possibility to provoke understanding and empathy, even just a little tiny bit? Because you think about people coming into exhibitions, particularly Venice, I mean, to change somebody's view is so hard, right? We have learned. But if this dial inside of them even just to turn a little bit towards empathy for the situation and actual people that are living through this, I think that is already a huge gift. Yeah. So I think that is what I feel strongly about.

HL: I want to pull things full circle here by turning the attention from this recent exhibit in the current geopolitical crisis to something that becomes about the future and also about some of your own thoughts on things. So you have two very young children. How are they impacting the way that you think about the future of art and the future of museums?

AC: Oh, funny you'll ask that. I think after "Everyday War," one thing I learned from "Everyday War" is the reaction from the audience and how they react to the sitting. I actually want to do more of that. I don't know about others, but I do feel like going to art exhibitions, particularly contemporary art exhibitions, you get very exhausted afterwards because there are so many insightful ideas, smart, sharp observations about reality that you're learning. But to the extent sometimes I feel it's too much and almost too smart in a way that I don't think I could digest or absorb, and then I get annoyed.

And those are the kinds of things I can't communicate with my kids, most of them, not for a long time. So nowadays, I actually really want to think about how I could curate shows that they could participate. Even simply just, one of the only things that my kid did at "Everyday War" was climb up to the sofa and want to jump on it. And I think I did something. At least there's one thing in there that he could participate.

And then also, except for the table he was a little shocked by it, but then everything else is very easily accessible. I don't need to worry about him touching anything or breaking anything. So that was the part that I think is a big motivator for me to think about future exhibitions. I want to think about the exhibitions I'll do in the future have multiple openings, as many as possible, and that they could access the exhibition in multiple ways.

And looking back, it has been a long time that led up to Venice and then from Venice to San Francisco. But if I tell you, I think the two things for the exhibition, one is the talk-back that people were writing down what their everyday war was, almost like a tree hole, that kind of thing. And then the other one was the chair. Actually, the chair becomes something so inspiring, and I think further on it. It's very difficult to do an art show that has the effect like that chair.

HL: I love this idea, and I want to connect the idea of the chair, the idea of empathy, and then also the current moment and the challenges. As you know as well as anyone, museums have been under great challenges from the current presidential administration and even before that due to COVID, and before that even there was a great challenge of engaging younger audiences. But you've mentioned that museums must transfer their, quote unquote, care for objects into care for beings. If you project that out over the next, say, 10 to 20 years, what does a museum look and feel like if that idea is truly adopted?

AC: That is such a hard thing, but I do feel with all the industries, particularly within culture, I feel there are so many things that museums need to change, of course the whole narrative, but the display, how the body gets into the museum and sees things, feels things. I think it really needs a very big makeover, but there's really great foundation for it. And again, we need to look into all the process that leads to what we're seeing in the museum as of right now, and that will drive us to a very different outcome. But we've got to be willing, but museum is a lot more complicated than the previous smaller organizations I was in. But the concept is the same.

"Everyday War" is the first fully bilingual exhibition in Asian Art Museum. Can that process be a model for all the future exhibitions? I think it can. Having comfortable chairs in the exhibition for people to sit down and actually allow them to just first get comfortably situated in the chair even before they look at the artwork. And then after they finish the artwork, they don't need to rush to leave because it's so comfortable. They allow them to stay a little longer. That is doable.

So these little details, as you're starting to pile them up, and change the vitrine, the display cases, can the pedestals be reusable? Can these chairs be reused again? Because so many museum productions are so costly. So there's so many processes. If we started to really go in and dig in and think about other ways of doing it, I do think that we are going to see very different outcomes.

HL: Abby, previously you've said that museums should not simply be caretakers of looted colonial trophies, but instead agents of what you called radical conversations that need to be had.

AC: And I also think I said how we can transfer or transform the care of the object to the issues that we're facing today. I feel like the sense of care is really important, and I feel like museums actually have been playing and could be playing a bigger role in terms of caring about the society at large. It started off with the caring of the object, the studying of it, the nature of the object. For our conservators in the museum, they actually all need to go through chemistry classes and really study the nature of the object.

And I kind of feel like nowadays, and particularly with contemporary art, the caring about the issue, I feel like we could take it even steps further. And it's not easy to do, but I think we are at a point in the time we're in and in the institutional setting that we're in, we are actually positioned to go to the next step. And of course, nobody can do it alone, and I feel like if we're willing to go there and if we think collectively, really think that is a direction, I think museum is a great place to do that. I think school is another one, but museum definitely could do that.

HL: And what is the next step or steps plural?

AC: I think like I said earlier, I actually don't necessarily see them as like a big step. The radical thinking needs to go down to the very basic, as basic as how we greet people, as basic as language. And I nowadays really almost don't want to use the word "access" because I feel like that word is becoming more and more formulated and becoming a little bit more superficial. I wanted to think about different kinds of languages.

But for example, how we respect, honor, respect and honor the agency of the artist, the culture that an object represents, where it was found and where it actually carries the meaning. And I think the kind of language that originated with the origin of that creation needs to be honored, respected, and in the institutional setting they need to be readable, audible, and spoken. And maybe we cannot get there all together all at once. But once you start looking at it and start thinking in that way, I do feel like these kinds of small changes can fit into the radical thinking and manifest those radical thinking and is very approachable. It's doable. It's something that we could take action and make that change that actually seems both reasonable and radical at the same time. And I do think that's doable.

Having worked in the museum and having seen how that manifested in action in reality, I think it is possible. But do we want to do that?

HL: Previously, you mentioned the couches that you guys had in "Everyday War" and how having those there gave people a place to sit and actually relax as opposed to the typical benches which are very uncomfortable, and that it becomes like their own living room. And I thought it fit into the exhibition as well. It seems like that's one of those ideas that's reasonable as well as radical, giving a place of respite from society as a whole.

AC: Completely agree. And also think about there are lots of scenarios where you're looking at a time-based media without even having anything, without even having a bench. You basically have to stand there and watch. And it's one thing if the artwork was specifically requesting that people have to stand in order to appreciate that work or something, but a lot of them don't necessarily have that kind of requirement. But just, I think you could call it a blind spot or just insignificant at times.

But more and more, not just me but I went with a lot of my friends both in the art field or not, all started to have this feeling that actually going to see an exhibition could be very exhausting. So it's very physical, is very mentally demanding. You need to think a lot. So I feel like for us as welcoming people in, what does that welcoming constitute? And is it reasonable? Yes. Is it radical also too? And is it doable? Is it changeable? Definitely.

Yeah, that's kind of what I see it. And then a lot of times these big concepts when they get first introduced, I always like to think how that can be applied in small steps or bite-size, because that is what one individual would start first advocating for it, talk about it, and then slowly see that becoming a reality. And if you think about if you got many people start doing it, then it's a huge impact, but to demonstrate is actually possible and doable is very important.

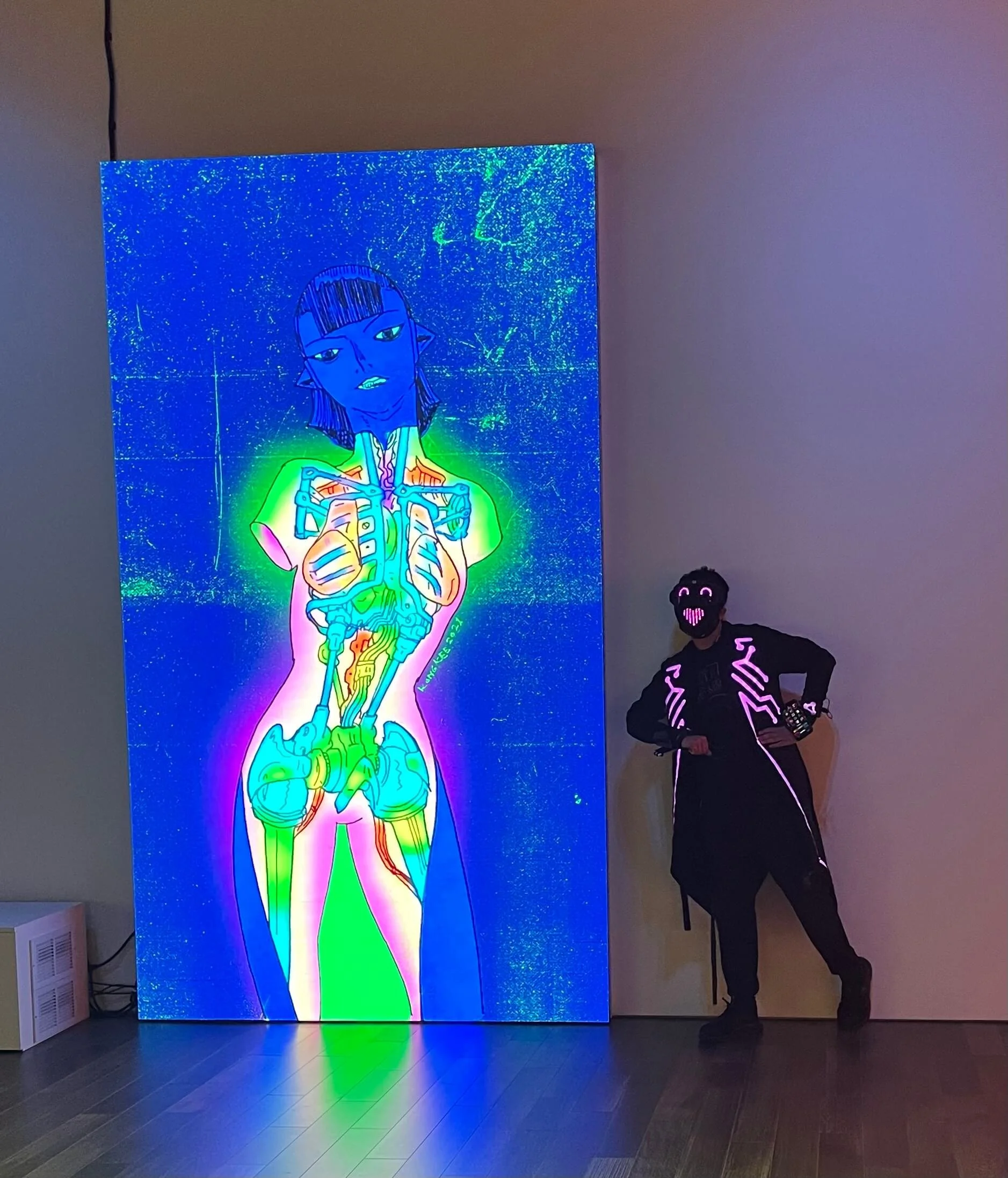

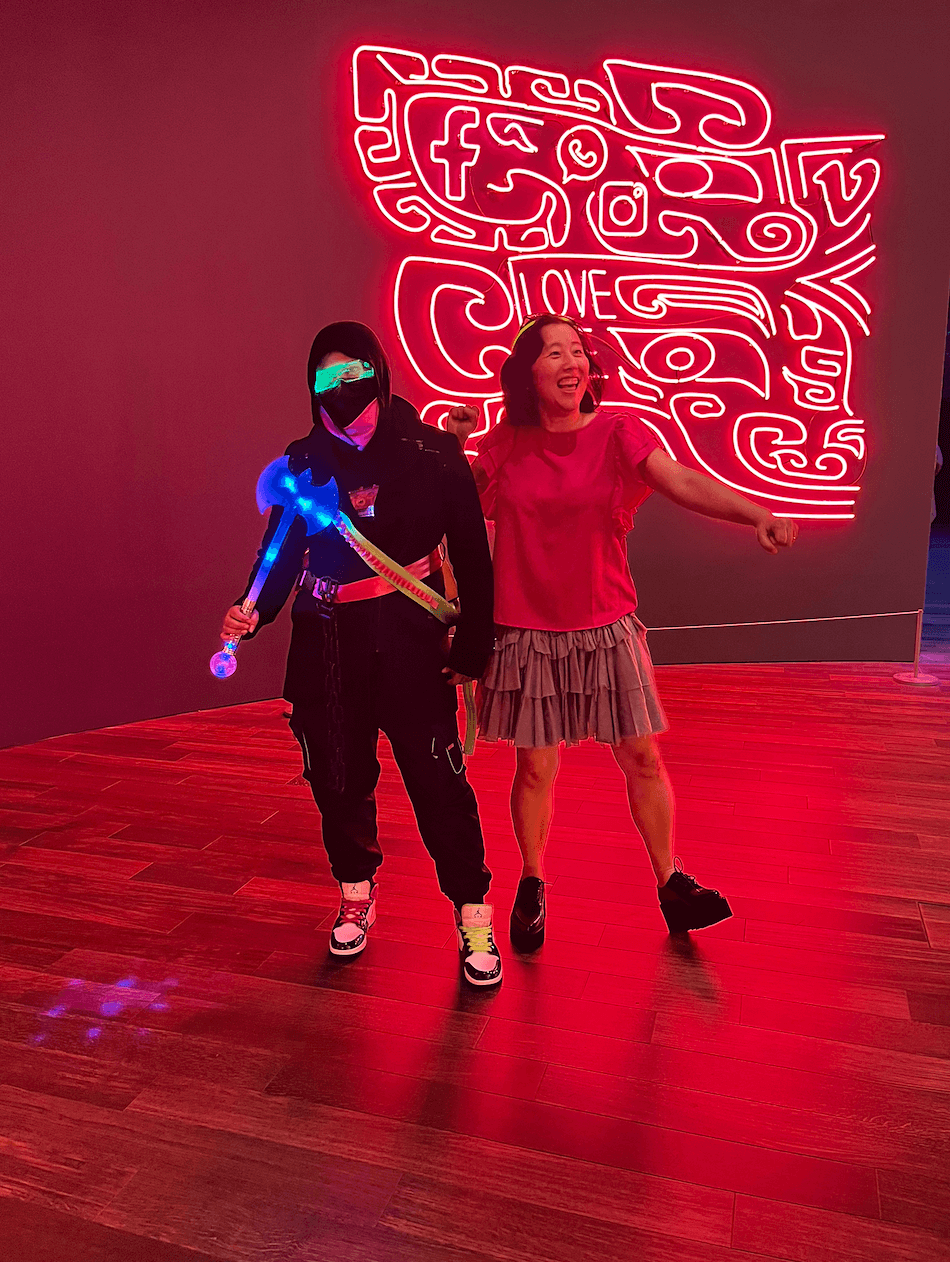

HL: I want to connect on the future of museums. At the end of our conversation the other day, we had spoken briefly about the idea of the challenges that museums are facing from not only the current administration and then also COVID and even before that, even before COVID, say 2019 and before that, there were challenges to bring in younger audiences that are typically digitally native audiences and how to get them interested. And centered within Kongkee, the Warring States cyberpunk show that you did and had an incredible ability to attract a very young, tech-savvy audience, diverse ages to the museum where you put ancient bronzes aside, Asian futurism, street culture, and video projections. What made that exhibit such a great hit with a young diverse-aged audience? And how can struggling institutions repeat that sort of success that you had?

AC: Oh my god, that is totally uncalculated. And I'm also very cautious about this idea about how do we duplicate a model or repeat a model or something like that, because when you think about, I mean, of course a model fits into a mold, right, supposedly, or you create a model so that it can be duplicated. But at the time when you create a model, most likely there hasn't been one before. That's why you create one. And as much as I want to repeat that, I actually don't know how.

I think Kongkee came out sort of, well, random is not the right word. It came out without us knowing what could have happened. And I remember even within the museum I was presenting this idea that we're going to do Kongkee and how we're going to do it. And I have to say, I always actually like to have small talks with our non-art colleagues. So like our security colleagues or in this case it was a facility colleague, but then on the other hand he's also a musician in addition to his regular job. And he was like, first of all, no one associates this museum with that kind of artwork.

And I really enjoy hearing that before we're going to do the show, and just to hear how unexpected that was kind of is telling me that that's the right way to do, that's the right path to go. But then on the other hand, before every show I become anxious and that kicked in, and I said, well, I don't know how many people it's going to draw, and he was like, nobody knows. And that was very assuring coming from your colleague and just basically comforting you, hey, nobody knows how many people you can draw, but this is very unexpected. So there is this unspoken part that, let's try and see what happens. But there is a sense of excitement I can feel around my colleagues.

And I remember there was a miscommunication and a mistake that happened on my part with the artist on the design side. And I felt like, oh, you know, Jesus, I have put my design colleague through this, a lot of time that she's been working on this, and then I probably gave her the wrong information. But very quickly she forgave me and then said, "Oh, let's move on. He's such an incredible artist. I'm willing to redo this thing and to work on the design that we all agree." And so when there's really a great excitement around a certain kind of direction, I do have a lot of people forgiving me on making mistakes. And I do feel like that part is important, with this tolerance of mistake, calculable mistakes or mistakes within certain kinds of boundaries, that when an institution is willing to take some risk, you need to allow rooms for error and different ways of doing things.

And with Kongkee, I mean, again, we have to really build this and believe in this trust that we should have with the artist. I think the exhibition could become this successful is largely because Asian Art Museum itself is so uniquely positioned with all of these bronzes and archaeology items that Hong Qi was only reading them in books that gave him the inspiration to create his animation, but actually seeing them in person and he quickly picked out the ones that he just saw a direct connection with his work.

And then our previous director Jay Xu often said that there's actually no antiquity in Asian Art Museum. They're all contemporary art. They were all created by the contemporary artists at their time. So that was a huge inspiration for Kongkee as well. And so when he looked at these bronzes and the tomb figures, he just felt like these are the characters that he's been drawing and he's been having conversation with and has been very essential part of his whole storytelling.

But then he also said, you know, as an animator, my job is to animate these objects. So that's why he thought about having this kind of flickering changing neon light behind the object instead of like normally when you light an object it's from the top or sometimes from the bottom, seldom from the side, and he did it from the side with this changing flickering light. So in a way it animated the objects into his whole storytelling, and it's not just one thing. It's not just like, oh, let's have a designer redesign these cases. No, he actually had a whole narrative set up and this is just one small tweak. And you look at the tweak, it's very simple. And our very talented staff very quickly figured out, like, this is his concept and how they can execute.

And by the time that they were shown together, I mean, across from his LED GIF artwork, you just see kids just flock to the pedestal and looking at it and wanting to know what those are. So that gave me a huge opportunity of learning because I've been thinking about how we can break away from this idea of colonial trophies. This idea of precious items is not meant for us to see them as part of our life but to only see them as a part of control and authority. So but I couldn't really figure out why and why I couldn't do that until I started to work with Kongkee.

Basically it's not just a design trick, it's really the whole narrative got changed, and within this bigger narrative you start seeing things in a different light. I mean, literally in this case it's different light, and then you feel like these objects got liberated and you reclaim the ownership and agency. And that was huge for me to start to see when we're talking about a futuristic Asian culture that this kind of alternative thinking, and you can even say an alternative way of exhibiting, all of a sudden became a reality.

And the audience came built on word of mouth. We were seeing the audience at first, it's just like slowly getting more and more, but those are just typically every exhibition sort of starts like that, and then slowly, and then all of a sudden we had a surge and then it kept going like that. So you realize people can see this all on social media, but still it's really the word of mouth.

And I remember I was giving a tour and this guy just started following us and wanting to hear more, and he's from Taiwan, and then we started talking, and then I said, "How did you know about this event? How did you know about this exhibition?"

And he said, "Oh, my Vietnamese friend told me about it."

So this is another thing. I feel like there is a fatigue about this future narrative that so often got told by Hollywood, by the mainstream, and there has already been a lot of criticism about them, and it's important that we started to build awareness that, okay, we should not be using the same way to display these trophies. Okay, what is the way to display them then? And I feel like we got a little stuck there. And I myself included, because when Kongkee happened in 2023, and that was already four years into the job, and I've been just thinking how we could do it differently, and again, it's really learning from the artist and the audience.

And then so as the audience started to come in, and we never had this many, all kinds of regions in Asia that were coming in, African American audiences, Latin American audiences. And I remember one of the African American artists that was talking to me and she's also an artist herself, and she was like, "I am so excited now that I'm looking at the show, and you know for us we talk about Afrofuturism and there's a big also a difference between African American futurism and Africa futurism. So then you know what is this? Is this Asian American futurism? Is this Asia futurism?" And started to really want to know more and having a conversation about that.

And it was from that point on I realized why there are so many people coming in. And I was so glad to see there was even a short essay that was written by, I mean, judging from his face and name it seemed like a South Asian tech person in Silicon Valley. And he wrote about his reading of the show, his experience with the show.

So it started to make me realize that we were all hungry for an alternative future. And we can't just simply stop at where we say it's not. We need to show, we need to say what it's like. And I feel like for me it really demonstrated a new way and a new possibility for the museum. And that's why you see crossing age, crossing race, crossing social status, crossing generation, they come at the same time.

HL: That's fantastic. Thank you. So maybe as a final question here to see if we can pull everything full circle is to hear your thoughts sort of prognosticating on the future of museums, especially as it relates to younger audiences and new technologies. You know, a lot of institutions are under pressure to deliver these, quote unquote, blockbuster exhibits that have social media moments that can spread things online while also doing this community-based work that allows for more traditional works to be displayed. So from your vantage point, how can museums avoid becoming purely attention economies?

AC: Very hard. Very hard. I think we all face the same pressure. I think every culture venue faces the same pressure. Nobody is exempt from that. I feel attention economy in so many ways is at least one of the big factors of why this institution can continue to exist. You cannot avoid that. But how do we create these attentions and sustain them?

And as a whole society, I think we're in a crisis because our own personal attention cannot be pinned down. And so to ask an institution to be the gathering of all the attention, and this is partially also what Kongkee is saying with that Taotie piece, is the cautionary tale against this greed for attention.

But I think as I look at it, my also how I'm dealing with this attention span for self, I think you try to survive. You try to at least survive this moment as actually so much attention has been grabbed by the virtual world. All the physical entities or physical appearance, theaters, cinemas and dancers, museums, I think are all facing a crisis. I think Hollywood is totally in panic too. I mean, some of their films that usually were the blockbuster got their lowest attendance in decades.

So I think all of these content creators, despite that we all say that content is king and whatever, but all the content creators are in this really crisis mode because we are facing the biggest attention grabber from the virtual world. And as you mentioned about the digital native, what gives me hope is that they were willing to come into the museum to see a show like Kongkee, that they're willing to come in to see something like "Everyday War." It's very different audiences.

But I do feel the challenge is how to survive this current moment. I don't know if it's going to get worse or get better or what does worse or better mean? And I feel like for many eras we do see the format of culture change. For example, having grown up in China, when I was young, I still remember my parents and my grandparents that they will hum the local Chinese opera, whether it's Beijing opera or Cantonese opera or something. So that is very attached to the local culture that each region will have their different way of singing, and we are in this era that is more and more of an era of indifference.

And so now I look back, a lot of those eras, a lot of those operas, those local operas, some of them are already completely died. Nobody knows how to sing that anymore. And those people who know we're probably facing the last generation. But I mean, a hundred years ago we don't have hip-hop. A hundred years ago we probably don't have breakdance or something. So you do have new different ways for culture to reinvent itself.

But at this current moment I'm hopeful for us to think both radically and reasonably what kind of action can be taken. But then at the same time, I'm also not super optimistic. I feel like it's hard to capture fast enough on what is developing, and even ourselves we couldn't grasp on what is the most important, what is the most. And then we've been saying that, oh, this is so urgent, we must act on it. But then at the same time I also feel nowadays I don't have that sense of urgency as much as I used to, largely because I feel like just to have that sense of urgency doesn't necessarily trigger anymore. Having that sense of urgency is kind of like urgency everywhere. So what actually needs to be done is actually to slow down.

But slowing down to do what? I think it's going to be again hard work, but we should also tell ourselves and each other that in order for change to happen we need to think, we need to act on the change that you endure the thoughtful process. Any kind of change without the thoughtfulness is not going to be good change.

And maybe it's aging that I do feel I have more patience than before. I do see the danger and the harm of this kind of quick change. I don't think radical change necessarily means speed. I actually feel like radical change requires us to think differently in a different speed, in a different dimension, and it's not about being quick.

HL: Abby Chen, thank you so much. That's wonderful. You got me thinking.

AC: I'm glad.