Beau Stanton

Beau Stanton's worldwide practice includes large-scale murals, mosaics, stained glass, and animation. He focuses on the specificity of a site and illustrates the parallels between past human narratives and contemporary human issues.

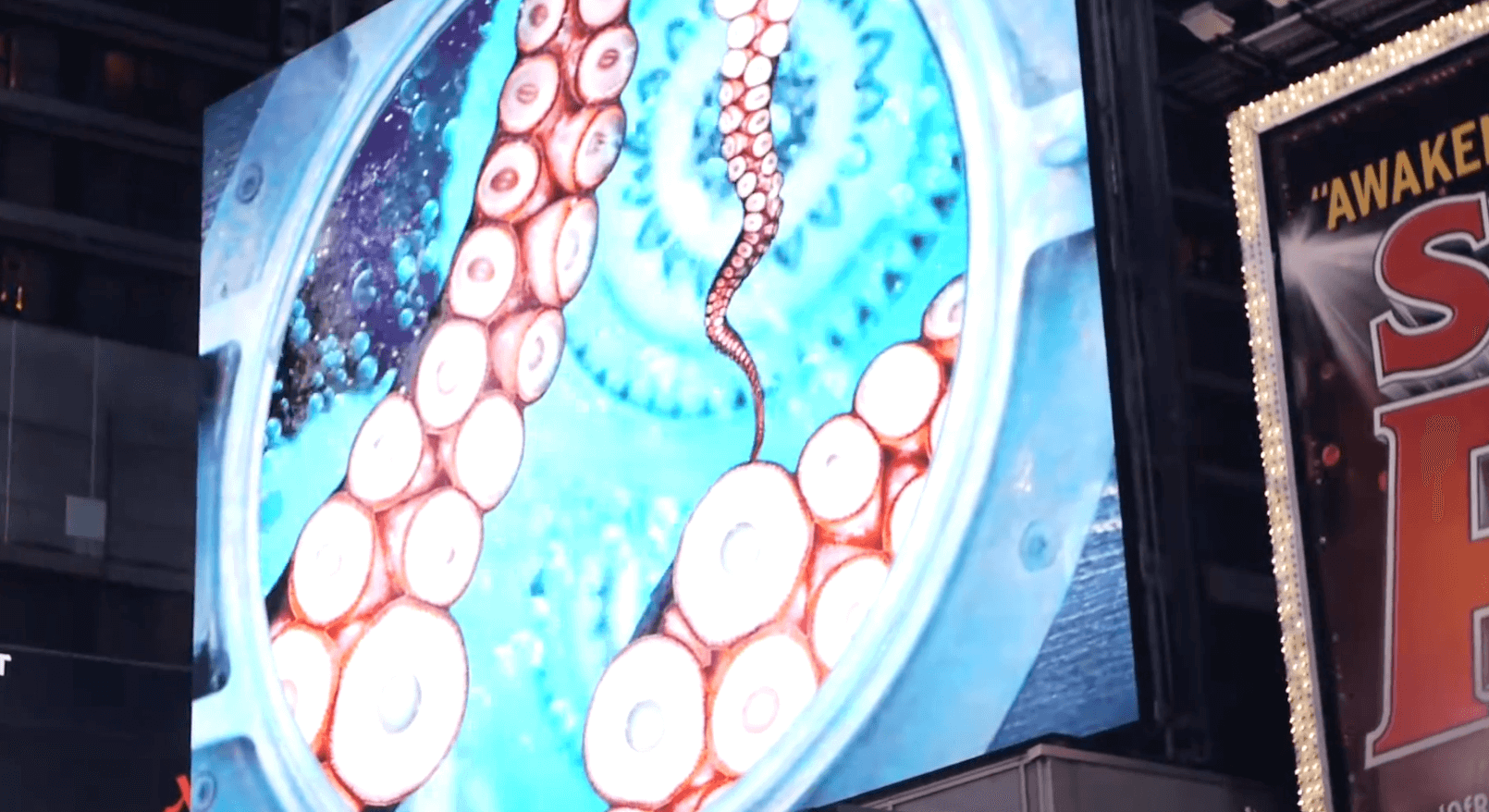

Stanton draws on classical ornamentation as well as sculpture, mythology, post-industrial, and nautical themes to create work that often centers on the environment and our place within it. Stanton’s work has been installed in a 13th-century crypt, on the Berlin Wall, across the electronic billboards of Times Square, and in galleries and on walls worldwide.

As of today, he has created over 60 public artworks in 25 cities across 16 countries. Notable project partners include The Nature Conservancy, the Albright Knox Museum, Times Square Arts, When We All Vote, The World Trade Center, PangeaSeed Foundation, The Explorers Club, The US Embassy to Italy, Wynwood Walls, and The Atlantic Magazine

The following are excerpts form Beau Stanton’s interview.

Early Career and Apprenticeship with Ron English

Hugh Leeman: Bo, right after college, you got a job as a studio assistant to the renowned pop artist Ron English. This is a role that you got, interestingly enough, by answering a Craigslist ad, and you ended up working with him for some five years. How did that apprenticeship shape you as a young artist and beyond art technique? What did you learn from Ron?

Beau Stanton: So I moved to New York in two thousand and eight from Southern California, because it seemed to me like the best place to pursue a career in art. And I had no idea really how to do that. I had gone to art school, you know, I'd been oil painting since I was ten. I had always been obsessed with making art, but I didn't really know how that translated into, you know, like being an adult person and making a living and all the rest. And so when I moved here, you know, it was right before the economic crash of two thousand and eight. And jobs for everybody were really scarce already, but especially for a twenty two year old with an art school degree that really isn't worth very much. It was tough. And I was doing a lot of interning for a couple of artists. I was doing a little freelancing, and I was just really trying to find my footing. And I got really lucky after about a month in the city after I responded to this Craigslist ad for a studio assistant. And I did know who Ron English was at the time, I had seen his work in a museum exhibition in Laguna Beach, California, which is the town I went to college in. And so I thought, oh, you know, this is a really great opportunity. Of course, I was applying to, you know, dozens of things a day. So I didn't really expect to hear back. And I got called in for the interview. It was in Jersey city, which is pretty far from Red hook, Brooklyn, you know, train commute wise. And so I got there really early. I got there like an hour early. And I remember seeing this guy, like walking up the block, kind of suspiciously looking at me like he knew that I was probably coming there for the interview and it was Ron. And so he and I just got along really well. And I ended up getting the job. And so, you know, he's an eccentric guy, you know, he's got a million ideas. He's always in his head. And so working with him initially was a little puzzling because you're like, what? You know, does he want to talk in the studio? Does he just want to work? And so it was really an interesting process, sort of like learning how he kind of maps out being an artist in the studio. And that was one of the biggest things, the first things that I learned, which was like, this guy is in the studio for twelve hours a day. He's painting nonstop and that's what it takes, you know, that amount of hard work. So fundamentally, the work ethic was the best thing that I learned from him. But then after that, it was technique. It was, you know, he hired me because I could paint in the studio. But then he started bringing me outside to help him with murals. So I had actually never painted a mural before working for Ron. I was always interested in them. You know, it was always an appealing thing, you know, learning about Diego Rivera and the big three and all, you know, I mean, throughout history, public art. But learning how to scale up what I could do small and make that was like, the big breakthrough. You know, that was the most exciting thing because it's very, very intimidating at first because when you're painting in the studio, your process is secret. You can mess up, it can have really awkward stages. And as long as you pull it all together before you take it out of the studio and put it on the gallery wall, you know, everything's fine, but you're baring it all when you're painting in public. And so that was a major hurdle and just started learning to embrace process and embrace like people participating in the process and commenting on it halfway through and, you know, pointing at something like, is that going to be this? You know, there's all these unexpected kind of interactions that you get working in the public space. And so working with Ron, you know, he not only showed me what it took to be a professional artist, but then I got some of those very specific techniques and also just generally learning how to create a compelling image because he's a real master of that and being able to really grab people's attention with his images. Sometimes positive, sometimes negative, controversially. You know, he's a master of that. So I was fortunate to have him as a—I still have him as a mentor. I mean, I call him all the time and ask him for advice. So it was actually working for Ron, took the place of going to grad school, basically.

Hugh Leeman: Wow. He's the master. It's an interesting relationship that you're mentioning here. And you hit on something that's very interesting, this idea of the privacy that takes place in the studio, and there's a finished product, and very seldom does the public see what happens behind the curtain. But that's all very public.

Public Art and Street Art as a Democratic Medium

Hugh Leeman: When you're outside painting these incredible large murals that you're doing and you've painted in impressive and unconventional venues, there's a thirteenth century crypt in Bristol to fragments of the Berlin Wall, the electronic billboards of Times Square. You've mentioned that one of your favorite things about street art is how people can just stumble upon it and unexpectedly arrive at ideas that come with art in their daily lives. What's the importance to you in bringing art into these unexpected public spaces?

Beau Stanton: Well, obviously it's an extremely democratic, egalitarian form of art. You know, in the sense there's no barriers to entry like a museum or a white walled gallery. And I think that's one of the main things that makes it special. And then also, you're responding to the environment when you're painting and, you know, often there are obstacles in your way for getting up to this corner and you kind of have to—you're always problem solving in that space. And people are witnessing it from start to finish. And yeah, these unexpected interactions that you have with people when they're just kind of surprised to see something like this happening along their way to work or in their neighborhood. It's extremely rewarding. And also, I think that it's, you know, we're in a really special part of history because public art has gone global. Like, you could say street art or whatever, however you want to call it is the biggest art movement that's ever been because it's literally around the globe simultaneously. And I think that cities got to enjoy the fruits of it first, but it has fully trickled down to some of the smallest towns in America. And it's very cool to be a part of that process. Like a couple years ago, I had the opportunity of painting the first piece of public art in a very small town in rural Iowa called Monticello. And I painted this pretty large mural, especially considering, like, the size of the walls in that town at the kind of crossroads of two main arteries that went through Monticello. And everybody was excited about this thing. I mean, people—it was, you know, the whole town showed up for the unveiling when I signed it, you know. And that kind of stuff is so special. You know, I could be painting on the corner of Fifth Avenue and, you know, sixtieth Street and one of the biggest, grandest walls and most, you know, few people might look up, but, you know, it's New York, right? Like, people are not easily impressed. And you just you have this much more sense of involvement when you're painting in these smaller towns, which is very cool.

The Mural Renaissance and Contemporary Art Trends

Hugh Leeman: You mentioned the idea of street art and this globalization of imagery that comes with it. And there's no barrier to entry as there is, say, at a museum. You've spoken of it in the context of a renaissance of sorts. The Renaissance was, of course, well documented as a rebirth, so to speak, of the classics from the ancient Greco-Roman world, its art, politics and ideals. Of that you said, quote, we're in the middle of a renaissance in the United States and worldwide. It's part of a global street art movement underway for twenty years. End quote. What is being reborn in the mural Renaissance, and what is the street art movement say about the society that we live in today?

Beau Stanton: So I think that the sort of beginnings of this thing really started to go global because of social media and the internet, obviously, you know, that was—it was really well timed. And so the introduction of these different techniques that allowed you to like, get up really quickly and paint something because, you know, until fairly recently, there wasn't a lot of legal opportunities for artists to be creating large scale artworks in public, you know. So I kind of came onto the scene probably about like, you know, halfway through, right, as muralism was really starting to take off because, you know, in the beginning you had a lot of stencil artists because that's very quick. And other techniques, wheatpasting and stuff like that. So it's really cool to see that there's a huge value being placed on the handmade. I think that says a lot about right now. That places like these small towns are embracing having murals because having things that are, that make a place special. It's as a means to revitalize downtowns and all that kind of stuff. Yeah. In terms of it being a renaissance, I think that our society kind of ebbs and flows between placing value on representation versus like more kind of minimal modern kind of aesthetics. And I think that we've definitely been going through a period of becoming excited about representation and maximalism and bringing more color and kind of energetic imagery into our cities. So, you know, without trying to read into it any more than that, I think that those are the trends that I've sort of seen helping this thing along.

Hugh Leeman: In the representation, you mean in the sense of figurative work or figurative?

Beau Stanton: Yes. Figurative representation of some kind, I think has been, you know, when I was in art school, there was very little figurative representation in the actual like, art world. You know, it was anything that was considered blue chip was highly conceptual or abstract and that has changed a lot. I mean, there's a lot of very successful figurative artists in all echelons of the art world now, which is very exciting.

Gentrification and the Role of Public Art

Hugh Leeman: It's beautiful to hear your thoughts on the crossroads, so to speak, of America in many ways in this small town in Iowa, and the energy and the beauty that it generates for people's lives, if nothing else, just getting people together and coming together and finding some sort of civic pride in that. You've mentioned that just now in our conversation, and you've also spoken in other interviews, kind of the potential other side of the coin, we might say. So public murals, as you well know better than anyone that they become popular in urban revitalization, but they can also be controversial in neighborhoods that are facing change. You've noted that artists are sometimes blamed as, quote, the tip of the spear for gentrification, end quote. What are your thoughts on the role of mural art and gentrification and revitalization?

Beau Stanton: Yeah, I mean, it's—I think it's very important that we understand sort of the role that we play. And maybe the way that the public art is, is get people excited about. I think when I made that quote that was—that was a very hot topic. I mean, it still is, but I almost feel like most artists have just kind of thrown their hands up because it's like, how do we, you know, how do we not participate now? It's like it's so widespread, you know, and also I think it's if we're going to have to deal with the difficulty of gentrification and all of that, these new buildings have art on them, you know, like that's at least a silver lining. But I do think that this subject has become very potent and rightly so. And I do think that oftentimes neighborhoods are undergoing these changes and so part of the way to, you know, is to work with the local community and to also uplift the local artists when they're doing these types of public art projects for new developments. So, you know, I don't think it's ever going to be a perfect system, but I do think that that's a really positive development.

The Creative Process and Evolving Interpretations

Hugh Leeman: So murals, as you very well know, can take a long time with these extended timelines and not to mention their multiple partners that can have input on this from the people that are funding it, to the community that lives where that mural is at, to the building ownership, and then putting that at the confluence of something you've said previously, which is that art stimulates questioning. Everybody brings their own interpretation to the table. With these longer timelines and the multiple collaborative partners and community input and so on, and these multiple interpretations, how has your interpretation of a work that you did changed from when you first did it till years later when you see it again?

Beau Stanton: Yeah, it's an interesting process. I think I can see that pretty clearly, even six months after, or even just a few months after because, you know, often when you're working on something, your brain is in critical mode. You know, you're like, how do I solve this puzzle? How do I make this thing the best, you know, work of art that I know how? And so I usually don't—I'm usually not happy with the work until like months or even, you know, a year later when I can come back to it with fresh eyes, like a regular person, and look at it and appreciate it for its quality without my brain locking in on, oh, I need to do, you know, this kind of thing. So that space away from the artwork is really an interesting thing because then you can actually see it without your critical brain picking it apart all the time. But yeah, like I'm working on a—I've been working on a project for two years that is supposed to be executed this year. And it's really funny to have to look back on something that I designed two years ago and be like, all right, I'm going to jump into this now because, you know, totally different person, you know, two years later. And so it's a unique challenge when some of these projects are complex logistically and do take a very long time to get from, you know, the initial contracting all the way to the signature, you know, so it's tricky because you, when you—as an artist, you always question yourself. And when there's so much time between the design and the execution, you definitely have a lot more time to do that.

The Ava Gardner Mural Controversy

Hugh Leeman: The idea of this changing of interpretations you've just shared on this really interesting perspective of what goes on inside the artist's mind when there's multiple partners that have inputs on this. But then, as we spoke of at the start of our conversation, the idea of the community that lives with this and around this, and then of course, we can add on to that dynamic reality interpretations changing over time, especially with the idea of public art. I want to go back to twenty sixteen, your mural depicting actress Ava Gardner at the Robert Fitzgerald Kennedy Community School in Los Angeles came under threat of censorship. Its sunburst background was controversially alleged to resemble the Japanese Imperial Rising Sun flag, and it sparked calls for the mural's removal. But during the controversy, Robert F Kennedy Jr wrote a passionate letter defending your artwork, and even at one point he called the plan of censoring this—an obliteration of your murals, antithetical to all the values of American democracy and a searing offense to his father's memory. End quote. How did it feel to have someone of his stature draw such powerful historical parallels in support of your artwork?

Beau Stanton: Yeah. That was definitely a hell of a moment. To have—it was both RFK Jr and Maxwell Kennedy both wrote letters of support for the work at the—well, it was because of Shepard Fairey defending my work. And he actually sought out—he brought it to their attention because he had become friends, or friendly—he become acquainted with both of them after he painted a portrait of Bobby Kennedy, because it was at the location of the former Ambassador Hotel where Bobby Kennedy was assassinated. So that was the Kennedy tie in. Right. And the funny thing is, looking back, that was actually—I think this all happened twenty seventeen is when it all really kicked off. And this was obviously well before the pandemic and well before RFK Jr was known for his views that not everyone agrees with. Myself included. And so it's very—it's a funny relic of my past to have this letter from him defending my artwork, which I'm still very happy to have. It was a—it was a very much a tightrope walk for me because I wanted to defend my artwork from what I saw as sort of an arbitrary decision on the part of the school district to capitulate to a single subjective point of view without hearing everybody's point of view on the artwork. And so I was vigorously defending the artwork from the decision to have it whitewashed by the school district. The school district made that decision because of a Koreatown based community organization that sort of drove this push to have the mural taken down. And so ultimately having Shepard Fairey's support, RFK Jr's support, Maxwell Kennedy's support, Paul Schrade, who was also injured—he was a good friend of Bobby Kennedy in that kitchen when Bobby Kennedy was assassinated, he was a very old man—he also defended the artwork and also a large amount of other artists who painted the school also defended my right to have further discussion about what to do with this mural, which is really what everybody was kind of trying to say. And so I was very fortunate that I had that community rally around the mural. And ultimately that allowed me to have the, you know, the time to have a more nuanced conversation and actually do something thoughtful with the mural. So ultimately it was not whitewashed and ultimately I did not leave it exactly the same. I actually ended up adding to the mural to talk more about the history of the site and make it really—it actually ultimately was a better work of art after the additional layers were added. So it was a very tricky situation to try to assert some protections for public art and really stand up for that and stand up against arbitrary censorship on the part of the school district, while also listening to the concerns of that segment of the community and making them feel heard. So that was really my goal was, how do I thread the needle here? And ultimately, I was very fortunate that everybody was very satisfied with the outcome.

Navigating the Controversy

Hugh Leeman: When you're going through this because it's clearly not an overnight process, who was it that was giving you advice or walking you through some of these steps? As you mentioned, it's a tightrope, which implies that there's this fear that one can fall off and it will cause some irreparable harm in some way or another. How did those conversations—because you mentioned that there were, you know, this kind of community dialogue that was a bit perilous. How do those play out, the actual conversations?

Beau Stanton: Well, initially I found out about the fact that there was a group of people that were opposed to the mural just because I was contacted by South Korean media. So, you know, there's a few media organizations that operate in Koreatown in LA that are a bridge between the communities of the Korean diaspora that's in LA. And they contacted me to just ask me questions about the intention of the mural. And so initially, I answered the questions. I said, hey, look, this has nothing to do with Japan. This is a very common visual element that I've used in my work for a lot of years. A lot of other artists too. It goes back in, you know, thousands of years in history, and it's usually a symbol of, you know, it's usually kind of a hopeful symbol. And for me, it's really a visual device for kind of drawing in the focal point. And it also references Art Deco kind of style which really does tie in with the vibe of the mural and talking about that period in history with the Cocoanut Grove, which was now the school's theater and all that kind of stuff. So once, you know, I thought that would be the end of it, and it definitely wasn't. And then I started to hear about the other kind of outspoken criticisms of the mural by this organization. And ultimately, there were some images being floated—well, posters around the school, on the outside, calling for the mural to be taken down, which basically were superimposed a swastika over the background to illustrate that the mural was that offensive to this community. So, you know, at that point, I was like, okay, we got a problem. This is—this is—my explanation clearly was not adequate here. And so after I went through some channels to have any of the swastika imagery taken down, because that was my prerequisite for meeting with the organization, I ended up meeting at their little headquarters or their offices in Koreatown. And I had prepared a visual presentation where I talked about sort of the development of my artwork, why I used this symbol, where it comes from, you know, from my point of view. And I just, you know, I wanted to fully explain myself. I didn't want there to be any gaps or miscommunication through the channels, you know. And what I started to realize at the end of this meeting was that really there were—there was—the person who was leading this whole charge, I think really wanted to sort of control the conversation and ultimately wanted the mural taken down in order to dictate a new mural. And so at that point, I was starting to see that there were some other kind of agendas at work. And it just started to get a lot more complicated than I originally thought it was. Nonetheless, still met with this person a lot or frequently. We had some interviews together. We were on, you know, Larry Mantle's show on NPR. And we had some really good conversations and ultimately we just kind of got to a little bit of an impasse where, you know, I thought that the conversation was very useful that we were having because I think a lot of people, including myself, learned a lot about, you know, why this—about the sort of colonial period of Japan and brutalizing South Korea, why that is a sensitive spot. And also, you know, the—so we kind of came together on the sort of educational component of that. And then also I really wanted to be able to defend the mural's right to exist and have conversation around where we go from here. And so ultimately, I ended up hearing from another local organization called Quiapo, which is made up of Korean American women who are associated or somehow are very associated with the art world, actually. So museum curators, artists, gallery owners. And so after meeting with them later on, I ended up coming up with an idea, this idea, the solution really which was to add to the mural instead of taking something away, you know. So and by adding it was also in line with the original concept of showing some layers of history. And so this process of coming out of this really long kind of intense conversation and then adding additional layers to the mural, felt it felt honest, it felt interesting, and it also felt responsible. It felt like this was the right way to proceed because it's breaking the binary conversation of just keep it or take it down. And so for me it felt like the right choice. And ultimately I think most of the stakeholders felt the same way.

Impact on Future Public Art Practice

Hugh Leeman: It's incredible to consider the power of public art and the way that you've experienced it firsthand. With those experiences in mind, now that it's behind you, how did that experience affect how you think about creating public art since then, and how does it continue to impact the way that you think about communicating your intent as a public artist?

Beau Stanton: Yeah. So visual symbols, just images in general are very powerful and they can elicit very emotional responses from people, whether or not the artist intends that, you know, and that is the subjectivity of art. We all bring our own baggage with us when we see something, when we're looking at art and the takeaway really was, I want to—you know, I learned a lot from this experience coming out of this very intense process and learning about the sort of the other side of the coin, really, because up until this point, I had only had very positive responses to my public artwork. And so understanding there is another side of responsibility when you're painting in somebody's neighborhood and there should be processes in place to avoid artists getting in this kind of mess again. And I do think that most of the public art projects that I participate in generally will have a public comment period, and we'll show—we'll have the design available, particularly if it's not available completely publicly. It is available to, you know, city council meetings or something that it can be talked about and sort of have a little bit of a trial run, you know, just to make sure that there's not something that somebody didn't notice, you know. And I think that that's a healthy evolution to public art. Of course, we all want to avoid the dreaded art by committee, you know, or something like that, which is a nightmare. But I do think that there is kind of a happy medium where you can have community involvement in the process and also avoid something getting picked apart before it's even been made. So that's the delicate dance there.

Technology and Digital Art

Hugh Leeman: Several years ago, you worked on another very public project that ends up in Times Square, effectively taking your analog art—these oil paintings and murals, and turning them into the digital realm so that they could be displayed on a massive scale throughout much of Times Square for months. And the thing that becomes particularly interesting on this is that use of technology to begin to convert analog to digital. And these were animated in some ways that become a part of the story that was told with new technology from anything from, say, procreate on an iPad to, of course, artificial intelligence. How are new technologies being integrated into your art practice, and what do you see as being the future? If we were having this conversation years in the future, what are the future impacts of these technologies on artists?

Beau Stanton: Yeah, so the Times Square Arts Midnight Moment project was definitely a high point in my budding career. It still is. And that was twenty sixteen. That was a very big—I had a lot of really exciting things happen that year. And it was—I was given this opportunity because I had done several animation projects that were displayed as physical artworks in years past. And so I collaborated with a couple of animators. I had created a lot of the—basically, I created every physical element as like layers. And then I worked with a really talented animator on the first one, which I debuted as actually running on an iPad behind a salvaged porthole window for at Art Basel in Miami. And these were actual, like, editioned little artworks. And they were very cool. It was just a little like, forty five second loop or something like that of this little ship kind of rocking on this sea of these ornamental waves, like some of my early nautical paintings. And it was really fun. I really loved—it kind of got me hooked on taking what I do in paint, you know, my style that I've developed in painting and bringing it into other mediums, which I later would do in stained glass and in mosaic as well. And so I had done a few of those and I was introduced to the curator of midnight moment, Sherry Dobbin, by another curatorial partner and friend of mine, Laurie Zimmer. And so when I got that opportunity, it was a very overwhelming really thing to tackle because you can—you have, you know, there's several dozen screens that you can actually see at once and you can have more than one channel going. And so it was a really, really exciting project. And this was before NFTs were really a thing. You know, I mean, they existed, surely, but they were definitely not anywhere near the mainstream. I don't think, you know, anyone outside of kind of real crypto enthusiasts would have known about it back then. And so it was kind of cool to be doing this at a time when that kind of digital art really didn't have a platform, you know. And when the NFTs came about, I had all these animations from these projects and I was like, should I try to jump in these waters? And I almost felt like they were just of a different time and they just didn't have a place in this new thing. So I didn't actually—I have not NFT'd any of them. You know, maybe I could have made some easy money had I done that, which sometimes I feel stupid about not doing it. But, you know, sometimes you got to go with your instincts on stuff like that. And I just felt like it wasn't really honest to the work to use them for that. So but yeah, digital work is obviously now a very, very common, massive thing, whether in NFT form or in experiential things like, I don't know if you went to any of those like Van Gogh experience or, you know, all that kind of stuff is very common now because artwork as experience is such an industry now and it's cool. I mean, I think anything that gets more people to enjoy art is positive.

The Internal Landscape of Confrontation

Hugh Leeman: Maybe as a way of closing up here with one more question. So you mentioned earlier in our conversation this moment where you're walking into this meeting at the headquarters, the offices in Koreatown in Los Angeles to have this conversation. Clearly, that's this tightrope moment where you're walking into, you know, I'm almost thinking in the dramatic tones of, say, Daniel in the lion's den, where you feel like there's this conviction and your faith, but there's also the other side that is perhaps equally convinced of their belief and their ideology. When you're walking into that meeting, what was your internal landscape like in that moment?

Beau Stanton: Well, during that whole process, especially the first half of it, I mean, I was very much flying by the seat of my pants, just like really trying to be thoughtful and really not—I mean, the biggest mistake I thought I could have made was to be angry or defensive. And so I really made a point to listen, number one, and to be as understanding as possible and also keep, you know, obviously, continue to defend the artwork in terms of allowing the conversation to play out, really, which was my biggest goal. So I think you asked a little bit earlier, like how I was navigating this and, you know, if I was, you know, who I was listening to and, you know, maybe I should have gotten a PR coach or something like that, but this was all instinct. And, you know, I called my mentor Ron for some advice. I talked to Shepard a lot about it and some other folks, trusted confidants, which definitely is always helpful. But ultimately, it was a—it was a seat of the pants kind of situation.

Hugh Leeman: Beau Stanton, seat of the pants sort of situation. Thank you so much.

Beau Stanton: Thank you very much.