A Tale Of Two First Thursdays

Perspectives: A series authored by art world professionals on the state of the arts.

Like much of San Francisco, the Tenderloin has been in a constant state of transformation for as long as I can remember. In recent years, I’ve heard a lot of discussion about “changing the narrative” of the neighborhood, though I’ve lately begun to question why—and for whom—that narrative is in need of being rewritten. Today, the TL is often reduced to stories of open-air drug use and unhoused crises (thanks in no small part to the conservative media’s ongoing attempts to fabricate capitalism’s failures as those of the progressive policies of cities). But the Tenderloin is—and always has been—much, much more.

Among many other things, it’s a bastion of diversity, of unlikely friendships and camaraderie, resilient underground art and culture, and a great amount of humanity despite the immense levels of suffering endured here. It’s where the majority of my adult life has played out over the last two decades, and where almost all of my greatest loves and friendships have sprouted and taken root. I’ve met many of the most important people in my life here, and I’ve also lost many friends to the very hardships that led them here to begin with. For better or worse, as far as neighborhoods go, it has been the closest thing to a consistent home for me since I moved to San Francisco many years ago.

Moth Belly Gallery, San Francisco, CA

As is often the case, where some people find home, refuge, and community, others pursue only opportunity. This is something San Francisco has witnessed many, many times over the course of its history, and it has accelerated in the past few decades with the sprawling development coinciding with the migration of much of the tech industry to the Bay Area. With somewhere near 50% of its housing tied up in nonprofit-owned SROs (single resident occupancy hotels) and subsidized housing, the Tenderloin itself has historically been a very difficult place to gentrify, but that does not mean efforts have not taken place and are not currently underway. From the early to mid-2000s to a decade later, rent for a studio apartment climbed from $800-$900 to upwards of $2,000 or more; not to mention the proliferation we had witnessed of chic clubs, restaurants, galleries, and other establishments that had (non-coincidentally) coincided with the gradual closure of most of the neighborhood’s gritty yet beloved dive bars.

While rising rents and changing landscapes are by no means exclusive to the Tenderloin—or even to San Francisco—what has always stood out to me specifically in the TL has been the juxtaposition of these attempts to gentrify, with high rents and posh boutiques, against a backdrop of a full-on humanitarian disaster taking place in the streets. Despite the affordability crisis in our city and nation, and the fact that the Tenderloin has a long way to go before its most vulnerable residents are adequately provided for, it should come as no surprise that this is seen as little hindrance by developers. As a centrally located district in the heart of the city, it seemed only a matter of time that such sights were set on the area. And as is unfortunately the case with gentrification, it is art and artists that are often ruthlessly exploited to fuel its engines. What you’re reading is the account of one artist’s experience with these cycles, and their ongoing efforts to resist such exploitation.

Moth Belly Gallery owners, San Francisco, CA

A San Francisco Story (For Context)

The following is a common type of story in both the historical and contemporary fabric of the Bay Area—that is, a story of displacement. Albeit mine is a comparatively minor, even privileged one, when measured against the many devastating accounts we've heard of multi-generational families and residents—disproportionately those of color—having their homes and livelihoods uprooted entirely. I share my own experiences because I believe they may inform both my reasoning and my reactions to recent events.

Fresh out of high school, I moved from Stockton, CA, to downtown San Francisco in the fall of 2003. Just 80 miles west of Stockton, SF was the nearest cultural hub, and the Bay Area was the path of least resistance for a young and creative individual like myself who needed to escape the narrow-mindedness and lack of opportunities in my hometown. I spent the first couple of years living in lower Nob Hill, until 2005, when a roommate got me a job working the front desk at the Mitchell Brothers’ O’Farrell Theater—the equally infamous and iconic strip club formerly at the corner of Polk & O’Farrell—just before my 21st birthday. At the same time, I also moved into my first room in the Tenderloin, a block away from the club, and the 2-3 block radius of that part of the Tenderloin became my home base for the next 20 years.

While I enjoyed a few brief stints away over the years, I’ve spent the bulk of this century to date either living, working (or, for the most part, both) here in the TL. The majority of my 20s and early 30s were rife with alcoholism and on-and-off substance abuse, with in-and-out stays in several different bed-bug-ridden shared apartments and other suboptimal living situations in the neighborhood. I always somehow managed to keep my job at the strip club over the years, however, where I spent evenings battling hangovers and drawing weirdo art on the stationery and copy paper kept in the front office. I was also able to get a lot of my other barfly friends hired there, and we’d pass the time making zines with the Xerox machine or working on collaborative ballpoint pen drawings until the shifts ended late into the early mornings.

While still working at the club, the longest living situation I had outside of the TL began around 2012, when a friend and co-worker of mine moved out of their one-bedroom apartment in the Western Addition that they had lived in for several years and passed on to me. It was part of a four-apartment complex that had been in the owner’s family since the early ‘70s, and I was able to afford it because he was kind enough not to raise the rent of the little over $1000 my friend had been paying per month. As an adult, this was hands-down the best living situation I had ever had, and for years prior it was something I had only fantasized about and never thought that I would have been able to afford (and wouldn’t have been able to under normal market rates). The apartment was pivotal in helping me start to improve my life, and given the opportunity, I very well may have stayed there for the rest of my life. But, as it seemed too good to last—it was.

After two years, when the housing market was at its peak, the owner, like many others, decided to sell the complex. It didn’t take long to find new buyers, who ended up being a new-to-SF couple that had $1.2 million to invest in the homes of my neighbors and me. Their first move was kicking out my friends Joe and Lisa from one of the upper units, so they and their family could move in, and their next move was installing security cameras all over the property, including one that greeted me the moment I stepped outside my front door. Their demeanor and approach to my neighbors and me didn’t seem like they were prioritizing long-term neighborly relationships, and they weren’t. Within a few months, we all received notice that we were being evicted under the Ellis Act and had 120 days to vacate the property.

For those who don’t know, the Ellis Act is a loophole in California state law that allows landlords to evict tenants without fault under the pretense of “taking their properties off of the market.” In reality, it is mostly used so investors can boot long-term residents protected by rent control, in order to hike rents or convert the units into newer, pricier condos. The caveat is that invoking the Ellis Act comes with a slew of stipulations placed on the property owners, including having to keep the property off the rental market for at least five years. It’s in order to bypass this that landlords sometimes offer long-term residents enormous buyouts, often upwards of $100,000, to vacate their homes. This was not the case for my neighbors and me, who received the state-mandated minimum of around $5,000 each as required by the Ellis Act.

Moth Belly Gallery openings

The 120 days between receiving the eviction notice and leaving my apartment were rife with panic and anxiety—and with the rental market the way it was at the time, I began to feel like this might spell the end of my decade-long tenure as a resident of San Francisco. At my income level, working at the strip club, I basically had two options: either move into a closet-sized apartment or SRO in the Tenderloin, or try to find a roommate situation that hopefully wasn’t akin to the squalid flop houses of my 20s. As a now 30-year-old trying hard to hold my life together, both of these options were far from ideal. Then, almost miraculously, about two weeks before I was out on the street, my friend Emily got me an interview to take over her resident manager job at an apartment building near the corner of Post & Larkin. One week after handing over the keys to my Western Addition apartment, I was moving rent-free into one of the 43 units of the building I would be the onsite manager of for the next six years.

While not paying rent for that long was undoubtedly liberating in many ways, the apartment I was living in was anything but “free.” The way I came to look at it was that a resident manager is less like an employee of the property management company, and more like a tenant who opts to pay in time and labor rather than cash for their domicile. I soon learned that it was much more than time and labor I was exchanging, though, as supervising a six-floor apartment building on the outskirts of the Tenderloin in a lot of ways made my life more chaotic than I’d ever imagined possible. Regardless, not being suffocated by rent every month was a game-changer in allowing me to restructure my life more around my art. I was able to cut down on my shifts at the strip club, and within the first couple years of building management my art practice began to grow immensely. In 2018 I quit my job at the O’Farrell Theater completely, began a tattoo apprenticeship, and devoted myself even more to the things that fulfilled me—all of which I can at least partially thank my building management job for enabling me to do.

Tensions, however, began to brew between myself and the property management company, as I was given an inside look into their dishonest and often immoral business practices. As someone who had previously lost their home to the culture of treating housing as a commodity, I had found myself feeling increasingly implicated in the very system that had displaced me. This realization was fully actualized when, one day, I opened an email and saw—cc’d on the thread—the name Raimondo Forlin, the man who had evicted my neighbors and me four years prior. Apparently, he had become a portfolio/asset manager for the company I worked for, and I could only imagine that he’d used his successful Ellis Act eviction against several tenants as a credential in applying to work for that company. Little did I realize it at the time, but looking back I see that moment as the beginning of the end of my life as a building manager.

The year 2020 then came and hit San Francisco—and the world—like a hurricane. Despite the rampant fear, uncertainty, and death that besieged us, many of us also received a fleeting glimpse of what life could be like if our basic needs and expenses were met each month. Receiving government checks allowed me, and many others, to truly and exclusively pursue our passions for that short window of time. Between the boarded-up storefronts and the outdoors being one of the safest places to socialize, street art made its way to the forefront of my hobbies and through it I made many friends. There was also widespread support for the arts during this time, unlike anything I had ever seen before. Between the superfluous income and the solace many sought in art—and street art in particular—many artists, myself included, were selling work left and right. It was the first time I had ever experienced anything like it, and naively I felt like something had shifted: like we were entering a new era where the average person could get by doing what they love, because the support was suddenly there.

Moth Belly Gallery opening exhibitions

At the end of 2020, my new friend and neighbor KT Seibert and I had the idea to open a gallery and community space—both as a response to the mass shuttering of venues we’d seen in the Tenderloin and San Francisco during the pandemic and in the years prior, and as a way to foster and support the blossoming creative landscape of downtown San Francisco at the time. In October of 2020, we held our first of many fundraiser auctions to raise what we needed, and through the support of the community, we managed to reach our goal of $40,000 for opening expenses. In January of 2021, we signed the lease for 912 Larkin Street—less than a block away from my apartment building—in the space that would become Moth Belly Gallery for the next five years and counting.

By spring of 2021, I had all but checked out of my building manager job. Between the rampant nepotism and moral bankruptcy within the company, the increasing demands of the work, and the company’s responses to the events of 2020—which I considered tasteless, to say the least—I had had enough. In June of 2021 I finally decided to put in my two weeks’ notice: a decision that, despite the challenges that followed, I have never regretted.

Moth Belly community and art

A Jaunt Through The Belly Of A Moth

I would like to begin this chapter by prefacing that neither KT nor I had any idea whatsoever about where to even start when it came to running a gallery or small business. Aside from curating a few art shows at the t-shirt shop and lowbrow gallery The Loin that used to inhabit 914 Larkin next door to where Moth Belly is now, I had virtually zero experience when it came to any of this, and KT even less. While we both brought our own complementary skillsets to the table, and have managed to wing it fairly well, our complete lack of business acumen has made keeping the doors open a near-constant challenge. And while we never started this project with either the goal or illusion of making much money, I don’t think either of us anticipated how much ongoing work and sacrifice it would require—and for how little compensation in return.

We spent the first nine months of 2021 fixing up and renovating the space—painting, cleaning, installing drywall, and putting in light fixtures in an otherwise uninhabitable basement that has since become studio and office space for ourselves and other artists. It was countless hours of hard work but it was exciting and it gave us time to plan and to try to figure out what the hell we were doing as far as opening up a gallery space. As nervous, scared, and even doubtful as we were about whether this was the right thing for us to be doing at that point in time, when I look back, this little era was also perhaps the most magical. I guess you could call it the honeymoon period, if there ever was one.

On July 1st, I moved into Moth Belly in what was supposed to be a very temporary transitional juncture, but ended up squatting there for almost three years. Out of all of my challenging living situations, staying at the gallery that long took the cake as the hardest, hands-down. I was lucky a few weeks here and there throughout the year when I would be invited to house- or cat-sit for friends in the Castro or Nob Hill—but for the bulk of 2021-2023 I was camped out in Moth Belly with a sleeping mat and a rice cooker, showering at friends’ apartments nearby a couple times a week. At first, I slept in the basement, but the stale, damp air and the thumping bass from the neighboring bar led me to start sleeping upstairs in the gallery, where I’d instead go to sleep to the sounds of car alarms and the screams and howls of a neighborhood that increasingly seemed to be falling apart. At night I would console myself with the reminder of how fortunate I was to be inside and not in the tents and sleeping bags that so many others inhabited outside.

Moth Belly Gallery openings, community gatherings, and music events

It was also during this period that I became and remained completely sober for the first time in my life. After several failed attempts in the years prior, moving into the gallery coincided with me cold-turkey quitting cigarettes, alcohol, and whatever other garbage I’d occasionally put into my body while drinking. I think I knew that to both run a gallery and endure this living situation for however long it was to last, I couldn’t be subjecting myself to the hangovers, depression, and erratic behavior that had accompanied my habits. Metaphorically, opening Moth Belly Gallery was probably the closest I would ever come to being a parent, and I got my act together accordingly. It was also during this period that friend after friend of mine were dying from consuming drugs tainted with fentanyl—a fate that very well could have awaited me had I not changed my behavior.

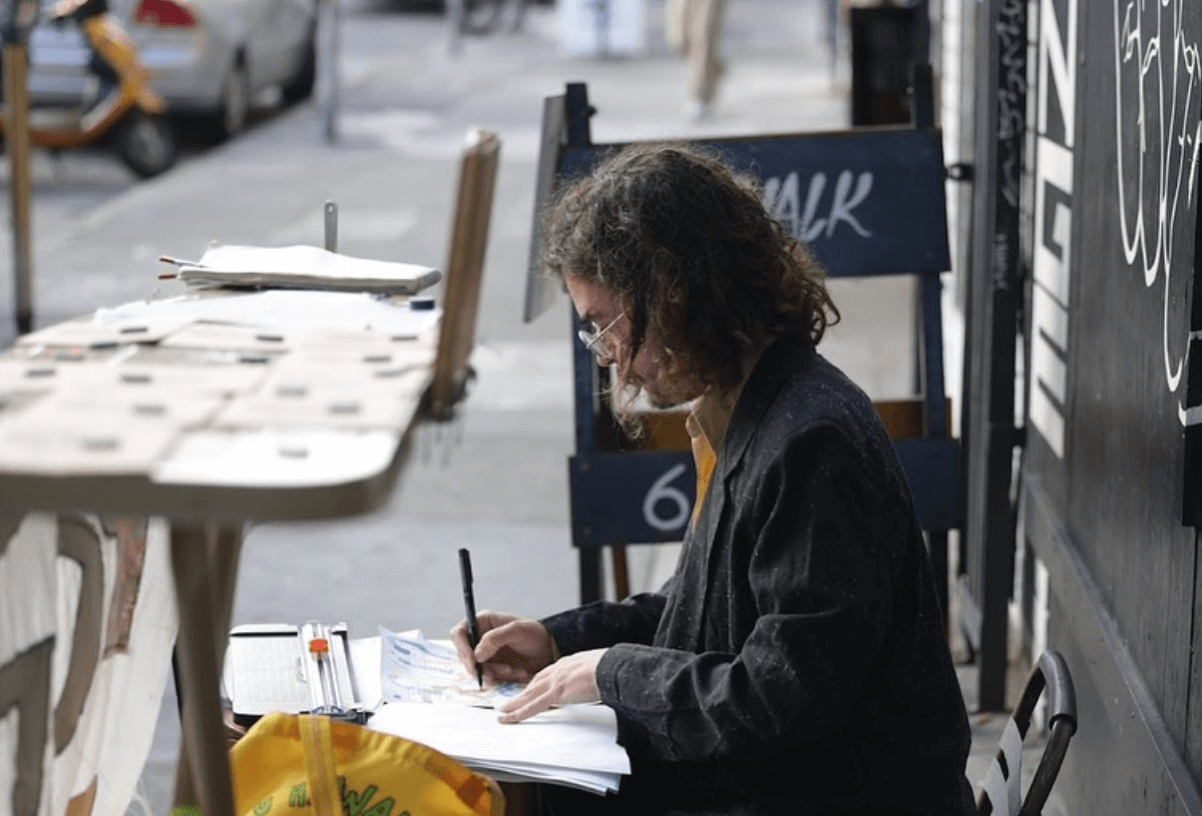

Moth Belly then officially opened in October 2021, and largely to success as far as we could tell. Our first exhibits mostly featured our new street artist friends, KT’s LGBTQ+ peers, and other painters, illustrators, and makers of all sorts that were close to us in the neighborhood and the community. I also began using our website to interview artists and creatives in the Bay Area as a way to give a platform to all of the new voices that were entering my life, and to document what was beginning to feel like a very special chapter in the history of the Bay Area art scene. Despite the persistent fear and doubt, things were taking shape, and the momentum could be felt.

I can say without hubris that, in a relatively short period of time, we became one of the more reputable and desirable-to-show-at galleries for many artists in the city, and the crowds seemed to keep growing and growing. Unfortunately, we’ve always had a hard time translating that traction into paying the bills while still upholding the DIY ethos upon which we were founded. By 2022, the majority of the support for artists that had blossomed during the pandemic had all but disappeared, and for us—and many in the Bay Area—each year has gotten harder since. We’ve had small wins here and there: the occasional $5,000 or $10,000 grant, or once-in-a-blue-moon home-run exhibit where we might not take a total loss, but they were always just mere dents in the enormous overhead of having a commercial storefront in SF and the never-ending barrage of fees, taxes, and monthly expenses that come with it.

Moth Belly Gallery bathroom.

Over the course of the next four years, we’re proud to have given hundreds of (mostly) Bay Area artists opportunities and exposure via exhibits, collaborative releases, and both printed and online features. On top of our exhibit programming, we’ve hosted a growing assortment of other events, including all-ages punk and hardcore shows, movie screenings, drawing nights, workshops, fundraisers, artist talks, poetry readings, artist residencies, endless varieties of pop-ups and craft sales, and one solitary (and disastrous) attempt at an open mic. We’ve also always done our best to let anyone in the community use the space free-of-charge or on a pay-what-you-want donation basis—the latest example being Harvey Milk Democratic Club who had been holding their semimonthly meetings in our space for the past year.

While very proud of all we’ve accomplished, and immensely grateful for all of the beautiful friendships and relationships that have been forged in and through our gallery, there is also a darker side that most don’t see—the brooding, insurmountable, and ever-present burnout. The lack of compensation aside (if I had to guess, I’d say we’ve been able to pay ourselves what averages out to about $5 an hour over the past 5 years of our work for Moth Belly), it’s the social demands that have by far taken the largest toll. Year after year, the one thing that never seems to change is the imbalance of all the wants, needs, and expectations placed on us compared to a level of support that has never quite lifted us above barely scraping by.

One of my biggest faults has always been trying to wear too many hats at once—sinking my heart and soul into one, two, or even three things has never been enough, and some insatiable impulse from somewhere inside me always urges me to take on as many pursuits as possible at any given time. The gallery, in a way, has been the perfect vehicle for this aspect of my personality. Looking back, perhaps the burnout from Moth Belly would have been more manageable had it just been a gallery, and not so many other things compounded into this one space and platform. And perhaps even more so if, on top of the gallery, I hadn’t been juggling so many additional responsibilities myself—including my own art practice, my sobriety, and, not least of all, the stewardship of the Tenderloin & Lower Polk First Thursday Art Walk.

A Tale Of Two First Thursdays, Part 1

The exact origins of the First Thursday Art Walk (@sffirstthursday) aren’t completely clear, either to me or those I’ve spoken to that preceded me. The earliest online artifacts I can find date to around 2011, the era of White Walls & Shooting Gallery and an array of other spaces that have long since disappeared. One thing that seems to be confirmed is that it began as simply the Lower Polk Art Walk, and absorbed adjacent Art Walks that emerged in its wake, including a Tenderloin Art Walk that started in the mid 2010s. It can also be assumed that it either sprang from or was inspired by the greater First Thursday event that encompassed multiple neighborhoods and was a popular gallery-going night in the 1990s and dissolved likely due to changing socio-economic demographics and overall culture shifts in the 2000s.

Throughout the latter half of the 2010s, and as far as I personally remember, the Art Walk was managed by Nico, the owner of Fleetwood—a gallery and screenprinting studio that formerly occupied 839 Larkin Street (where Rosebud Gallery currently resides). During the pandemic Nico took the opportunity to move Fleetwood closer to her home in the Richmond District, opening a new shop on Clement Street where it remains today. Fleetwood’s departure from the neighborhood almost perfectly coincided with our opening of Moth Belly, and Nico saw me—a diligent organizer and long-term resident of the Tenderloin—as the right candidate to pass the torch to. The opportunity aligned with our goal of combating the loss of spaces and outlets for creatives in the neighborhood, so accepting the role was an easy choice. In October 2021, just as Moth Belly officially opened to the public with our first monthly exhibit, I became the de facto shepherd of the First Thursday Art Walk.

If you’re unacquainted, the Tenderloin & Lower Polk Art Walk is a once-a-month event where galleries, shops, bars and other venues in the neighborhood hold openings or other activities in unison. It’s basically a strength-in-numbers approach to bringing foot traffic to our respective events and fostering community, and for many spaces—including Moth Belly—it has consistently been the single most important night of the month in terms of generating revenue to keep our doors open. At the time of the transition in fall of 2021, a lot of the Art Walk had been all but leveled after so many venues had closed or moved in the two years prior—and in the beginning there would be only five or six places open on average each month, including us, Tilted Brim, Low Key Skate Shop, and a few others. Regardless, it didn’t take long for the crowds to return, and in a short period the Art Walk regained its reputation as one of the more revered underground happenings in the city. Within a couple years, we grew those five or six spaces each month to 20 or 25 on average, pulling in larger and more consistent crowds than the Art Walk had seen even prior to the pandemic.

Art openings at Moth Belly Gallery

For the first 27 months of stewarding the Art Walk, I did so entirely on a volunteer basis. As the First Thursdays grew, so did the workload, which entailed event outreach, query handling, social media and promotions, and monthly map and itinerary creation. Those 27 months also consisted of a dogged pursuit to reacquire funding for the Art Walk after the Lower Polk Community Benefit District had decided to stop sponsoring it, since the majority of it was now taking place outside of its jurisdiction. After several meetings and phone calls with different city organizations and the OEWD (Office of Economic and Workforce Development), I found myself constantly being given the runaround, despite how obviously integral this event was to the struggling small businesses of the Tenderloin and adjacent areas. The impression I was given was of a mentality that questioned why the city should fund it when someone was already organizing it for free. All the while, I witnessed the city pour massive amounts of money and resources into initiatives like “Vacant To Vibrant,” which temporarily filled empty storefronts with pop-ups and galleries to incentivize landlords to not leave their commercial properties tenantless for years on end, or their sister program “ENRG” which funds ongoing street activations in effort to make parts of downtown seem like anything other than the ghost towns they have become.

After I had all but given up on ever finding funding, at the end of 2023 I was encouraged by the OEWD to apply for a 2024 “Mini Events & Activations” grant being awarded via the TLCBD (Tenderloin Community Benefit District), the neighborhood nonprofit through which many both public and private funds are distributed. For 2024, through the grant, we received $15,000 for the Art Walk. Not a vast sum, but after more than two years of failed pursuits, it felt like a huge triumph. Then, in early spring 2024, to my surprise, a friend forwarded me an article about a new monthly street fair slated to begin called “Downtown First Thursdays,” organized by the Civic Joy Fund in collaboration with local event producers Into The Streets, with the ambition of luring office workers and tourists to the otherwise declining Financial District.

For those unfamiliar with the Civic Joy Fund, it is a local nonprofit focused on neighborhood “revitalization,” founded by our current mayor and heir to the Levi-Strauss fortune, Daniel Lurie, as well as café owner and aspiring politician Manny Yekutiel, and funded mostly by contentious crypto billionaire Chris Larsen, along with Bob Fisher (heir to The Gap fortune), Marieke Rothschild, and others who sit among the Bay Area’s ultra, ultra wealthy. The organization has been riddled with controversy since its inception in 2023, with criticisms ranging from gentrification to political influencing, art washing (the use of art and artists to launder unethical practices), and new-to-the-lexicon “joy washing.” Not to mention the ties to Chris Larsen, whose other philanthro-capitalist ventures have included a near $10 million dollar donation to the SFPD for drones and mass surveillance technology.

Somehow, amidst the formation of their event, it appeared that nobody from the Civic Joy Fund or Into The Streets thought to take the initiative to reach out to the original SF First Thursday (which, mind you, is also located in neighborhoods that would be considered “downtown”) to see if a “Downtown First Thursdays” event might be stepping on our toes at all. So I reached out to them. Rather than provide much information via email, they insisted on coming and meeting with me in person to discuss the situation. By this time, I was already starting to be bombarded by phone calls, emails, and DMs from people—vendors, performers, journalists, and others—thinking that we were Downtown First Thursdays because of the near-identical name and location.

Community connecting at Moth Belly Gallery.

On April 1st, 2024, Manny Yekutiel and Katy Birnbaum (Founder/CEO of Into The Streets) came to Moth Belly Gallery to meet with me face-to-face. They admitted that they knew about the pre-existing SF First Thursday, and their excuse for not reaching out to us was literally that “things just moved so fast” with the event planning and they didn’t have time. They also claimed that their reason for holding their event on the first Thursday of the month was to coincide with SF MOMA’s free admission day, while simultaneously asserting that Downtown First Thursdays wasn’t an art-centric event and therefore not in competition with us. Their proposed resolution was offering to include our Art Walk in their promotions to help boost us alongside them, which was an easy and immediate “no” from me. Aside from not wanting in any way to be fiscally or reputationally tied to these people, I wasn’t about to let our very hard-earned, grassroots event become a sideshow to a big corporate block party in the Financial District. If that wasn’t an insult enough, they next offered to just give us a “grant” that we could use for our own promotions or however we wished. I told Yekutiel that I did not want their money, and that this was not about money. They said they would not change the day or name of their event, but the best they could do was begin referring to it simply as “DFT” to try to divert confusion. They also said they would “make it easy” for me to forward the mixed-up solicitations to them, which I told them I would not be doing (as I did not work for them). The meeting ended unresolved, as I expected it would.

Since then, as the steward of the SF First Thursday Art Walk, DFT has been nothing short of the bane of my existence. While the phone calls and emails have gradually decreased over the past couple of years, our Instagram account is inundated every month with people messaging us thinking we’re them, trying to collaborate with us on posts, or tagging us in pics or stories in front of DFT’s giant disco ball which has become somewhat of a mascot for their event. If you google “San Francisco First Thursday,” nearly all of the search results yielded pertain to DFT—with our website and the little press about our work becoming lost in the deluge of their multi-thousand dollar marketing campaigns. And while the Tenderloin & Lower Polk Art Walk community has been resilient, it’s hard not to feel that DFT has had a damaging effect on our attendance. There are several people I can think of who used to regularly attend and support the Art Walk, who since have begun spending their first Thursdays down in the Financial District.

Around the same time as DFT announced itself, I was contacted by a woman named Abra Allan who was in the process of organizing another monthly downtown “revitalization” event that would take place on Market Street via her organization “Market Street Arts” and operating with a sizable grant from the OEWD. She herself expressed some criticism of DFT and the way they were going about hijacking our event, and asked me about the possibility of holding this Market Street event of hers in conjunction with the First Thursday Art Walk each month. Based on that initial conversation, I had appreciated her reaching out and approaching the situation in a seemingly respectful way, and told her I would be more than open to the possibility of our events working together. I then heard nothing else from Allan until August 15th, 2024, when she emailed me to inform me that her event, now titled “Unstaged First Thursdays,” would be a promotional partner of DFT, and asked if she could partner with our First Thursday Art Walk as well. Of course, my answer was “no,” and Allan’s motives for having contacted me in the first place now, in hindsight, appeared questionable and even suspicious. The First Thursday Art Walk at that point had two massively funded, newly coalesced block parties casting their shadows over it.

The absolute worst part of all this for me was that over the following two years, in order to remain eligible for the grant for the First Thursday Art Walk we had been receiving from the TLCBD, I had been more or less ordered not to say or do anything that could be even remotely construed as critical or injurious to DFT or the Civic Joy Fund. Apparently, there were “conflicts of interest,” likely pertaining to overlap in donors (e.g., Chris Larsen) and affiliations with Manny Yekutiel. As if having our event walked-on and co-opted wasn’t bad enough, I was not even allowed to publicly attempt to create any delineation between the two respective First Thursdays, under threat of the little bit of funding we were getting being revoked. Anytime the press reached out to ask me about DFT and how it was affecting us and our community, I was instructed to simply refrain from comment. All I could do was try to focus my energy on our Art Walk, and repeatedly untag our Instagram account from the dozens of pictures of the giant disco ball that came in month after month.

Moth Belly Gallery owner and gallery goers

A Tale Of Two First Thursdays, Part 2

Fast forward to the end of 2025—Moth Belly Gallery is on its last legs (or wings should I say). Every year gets harder and our fundraising efforts come up shorter and shorter. We start thinking that barring the event of some miracle funding falling from the sky, we will be closing our doors for good at the end of 2026, if we even make it that far. It’s bittersweet, but between the burnout, the constant worrying about money, and the thought of toiling away in a city that feels growingly hostile to the arts, we accept it’s maybe best for us to just move on to the next chapters of our lives. Then—in November—our contacts at the TLCBD reached out to discuss proposed funding for us beginning in 2026, which would potentially include everything we could hope for: an increased budget for the Art Walk, salaries for ourselves, stipends for photographers, assistants, contractors, and even a new front gate for the facade of our building. It seemed like the Hail Mary miracle we were hoping for, one that might rescind the otherwise imminent fate of our gallery.

As the discussions progressed over the following couple weeks, I learned that these offers to fund Moth Belly and the First Thursdays were part of a bigger vision for the neighborhood, dubbed “Larkin Street Revival.” The plans included daily street cleanings, filling more of the vacant storefronts with small business grants, and recurring street festivals featuring everything from circus acts to performances from SF JAZZ, and organized in collaboration with none other than Into The Streets. The goal, they said, was to eventually rebrand this corridor of the Tenderloin as an “Arts District,” starting by amplifying the preexisting businesses like Moth Belly Gallery and our neighbors. Furthermore, upon inquiring where the funding would be coming from, we were informed—no surprise—that Chris Larsen would be the one footing the bill. As should be obvious at this point, it didn’t take much thought to conclude that I would let neither my labor nor our space have anything to do with these efforts. I reached out to the TLCBD to let them know that I would be respectfully declining, and that unfortunately, the time had come for me to sever ties with their organization.

Before proceeding, I should interject that I have no intention of villainizing anyone at the TLCBD—since we opened our space they have been incredibly helpful and supportive of us every step of the way, and generally do a lot of important work in the neighborhood. Everyone I’ve met who works for them also, in their own way, genuinely cares for the Tenderloin and wants to see it thrive. I also understand that, especially in our current economic climate, organizations like the TLCBD need to take whatever funding they can get—public or private—and selectiveness is not a luxury everyone can always afford to exercise in the nonprofit sector. That being said, it has become apparent I have some major philosophical differences with them regarding what our neighborhood needs right now, and it’s my opinion that it isn’t a sleek makeover aimed at transforming it into a trendy and up-and-coming place to live. We’ve all seen what similar initiatives have done in neighborhoods like Bushwick in Brooklyn, and Boyle Heights in Los Angeles—and they almost exclusively result in erased cultures, higher rents, and ultimately displacement.

Moth Belly magazine with Bay Area artists interviews and t-shirt

All opinions aside, however, the move to bring that same money—and the same people behind DFT—into our neighborhood to manufacture this rebranding was something more than an ideological difference at this point—it was personal. If watching this cabal of billionaires and their money usurp the First Thursdays wasn’t hard enough, not being able to speak up or do anything about it for two years has given the umbrage I’ve carried plenty of time to ferment. This was, not to mention, compounded by the recognition of the greater motives at play—to further transform San Francisco into a playground for the ultra-wealthy along with their ensuing urban development and unchecked tech experimentation (e.g., Waymo). Offers to bolster and fold the First Thursday Art Walk into this “Larkin Street Revival” program struck me as a textbook example of Art Washing—because, of course, if efforts to “revive” and gentrify a commercial corridor are underway, what better place to start than with a monthly art walk?

Beginning on January 1st, 2026, the First Thursday Art Walk officially found itself without funding once again—and admittedly of my own volition this time. The TLCBD offered to try to find additional funding that did not come from Chris Larsen’s $5 million donation, but I decided that the affiliation, even if only by proxy, was too strong, and I was thus resolute in cutting my ties with them. I did, however, acknowledge that while I was the steward and the main organizer, I did not start nor own the Art Walk. It was a community event, and the community ought to decide what was best for it. If the community chose to take Chris Larsen’s money, I would not stand in their way—however, neither I nor my gallery would have any part in it. On January 27th, I called a meeting that brought together a congress of those of whom I considered the most active participants of the Art Walk—those who regularly organized events each month and had some level of investment in the growth of the First Thursdays. The objective was to educate everyone on the situation, share opinions, and discuss whether they as a whole wanted to accept this money, and if not, then what to do in the interim until alternative sources of funding were found.

Gallery openings and community connecting.

Among the dozen or so small business owners and representatives present, the consensus on whether to take the money was generally divided. A few people wholeheartedly stood behind my decision, while a few others were quite vocal in their beliefs that the money could benefit the community. Most, however, acknowledged both the pros and cons equally and expressed little more than indecision. One of the biggest arguments for accepting it was that the money was going to be allocated to the neighborhood anyway, and as the pre-existing small businesses here, we should be the ones to receive it and put it to use. An understandable perspective, but one that, for me at least, begins to break down in light of the increasingly exposed designs underway in the reshaping of our city to fit the wants and needs of a select few at the cost of many. And if we believe these billionaires are inherently unethical, along with their constant bypassing of democracy through “charity,” the question remains: how can we accept their contributions without incurring the moral and existential toll?

While no conclusion was reached at the meeting, more or less everything was laid out on the table, and it was decided that the matter of accepting Chris Larsen’s money would be put to a vote in the coming weeks. This would give everyone time to do their own research and come to their own conclusions before making a final judgment. The Art Walk now sits in limbo, and the future of its governance rests in the hands of its most devoted participants.

Go To Hell With Your Money, Bastards

Of all of my favorite pieces of dusty, twentieth-century art history lore, one of the perhaps most inspiring is the response of Danish artist and thinker Asger Jorn (co-founder of the COBRA group and Situationist International) to receiving the Guggenheim International Award in 1964. The esteemed award, which included a $2,500 prize, was promptly rejected by Jorn who, via telegram, immediately responded with “Go to hell with your money, bastard,” and a demand that public confirmation of his refused participation be made. In a day-and-age when selling out is not only increasingly acceptable, but the active goal of many artists and institutions, the sentiment of Jorn’s telegram rings for me now louder than ever.

While the term “art washing” itself is relatively new, the practice has existed in many forms over the course of not just decades, but centuries. As early as the Renaissance, the aristocracy has used art to both launder any number of their own misdoings and as attempts to share credit for the achievements of greater minds than their own. Jorn most certainly saw past this veil, just as many now collectively recognize the sly employment of artists, muralists, galleries, and subcultures as tools for real estate speculation and development. Given such understanding, I would think the choice to not accept money from the likes of Chris Larsen, Daniel Lurie, or the Civic Joy Fund should be an easy one.

The unfortunate reality, however, is that the reigning narrative of modern-day San Francisco just may no longer be one of conviction, compassion, and standing up to power that it has historically been touted for. That narrative has been replaced by one defined by mass surveillance, hostile anti-houseless architecture, and the full embodiment of our century’s tech-entrepreneurial response to Manifest Destiny. And the remaining pockets of genuine culture and community that exist here seem under constant threat themselves of either co-option, exploitation, or eventual displacement. For those of us who are still clutching onto some vision of the San Francisco we fell in love with however many years ago, the choice is now ours as to whom we align ourselves with.

Moth Belly Gallery’s community of creatives.

I know a lot of people view the Civic Joy Fund and their donors and affiliates as some sort of vital and even necessary force in the resuscitating of our city and in helping it to thrive. Others, like myself, see it as yet another arm of the technocratic billionaire class’s crushing stranglehold on the soul of San Francisco, but all the more nefarious in its masquerading as culture, equity, and inclusion. It is of my humble opinion that a city is not “thriving” when a small group of the ultra-wealthy are having to bankroll endless free street concerts and activations to try to make the city more fun for exactly the same class of people who helped decimate it in the first place—especially when those activations are co-opted and at the expense of pre-existing traditions like the Tenderloin & Lower Polk Art Walk.

A city thrives when working-class families, individuals, and artists can afford to live in it and aren’t constantly suffocated by rent, rising costs of living, and the looming fear of eviction. A city thrives when workers, students, and small businesses are supported both by infrastructure and by demographics of people who not only inherit the city but are actively interested and engaged with it. San Francisco’s problem for too long has been pandering to an industry of people who are generally detached—and whose only incentives for living here lie in the close proximity to their tech jobs and the convenience of being able to order a near-infinite variety of meals from DoorDash while they isolate in the safety and comfort of their condos and can only be lured out with enormous (and free) block parties.

As I write this, the corporate street fair known as DFT, about which I’ve hitherto been prohibited from speaking, continues to rage on at the start of each month, along with the endless other events and activations they’re trying to use to invigorate San Francisco and, in turn, preserve the investments of the city’s wealthiest shareholders. Meanwhile, the future of the First Thursday Art Walk—or at very least my involvement in it—is precarious. These recent events have led me to do some deep introspection about whether a gallery like ours, and a monthly art walk, can even exist at all in a neighborhood like the Tenderloin without, in some way—if even inadvertently—feeding the cycles of gentrification, no matter how intent we’ve become on resisting them. Looking back, I question whether my endeavors to work with the city at all have been the right idea, and whether my efforts would have matured better had they remained in spite of, rather than in collaboration with, these institutions shaped by conflicting incentives and entrenched in the power structures that govern San Francisco.

Moth Belly Gallery, bringing the community together.

Documenting this all has also prompted me to do some serious ruminating on not only my own complicity, but that of artists and galleries in general within these extractive economic systems we’re immersed in. Unless one keeps the creative work they do entirely divorced from commerce—and I praise the few that do—there is no practical way to vet every transaction that helps uphold our practices. As the adage goes, there is no ethical consumption under capitalism. This raises the question: when, and where do we then draw the line? For me, I’ve concluded it’s when my work risks being weaponized, either directly or indirectly, to perpetuate harm or promote the agendas of those I stand in moral opposition to. Witnessing what has happened in San Francisco over the past few years, I’ve grown to understand how challenging it can be for artists to evade such agendas, as they often arrive disguised as much-needed patronage and support, and prey on a financially vulnerable class of people. But that does not excuse us from having to ask ourselves these hard questions, and with what’s happening in our city, the time to be asking them is now.

The closure of Moth Belly Gallery at this point may be all but imminent, but I’d much prefer that over having our legacy tainted by any affiliation to the rampant sterilization of this city and the billionaire money propelling it. Besides, five years is a long time to have run a space like ours, and it would be in line with the ephemeral nature of DIY, artist-run galleries to clock out around this time. If that means getting a regular job again, all the better—as I’m at a point where I’d rather do that than continue to be constantly beholden to the interests of others when it comes to the things that I cherish. And if that also entails the true end of my now 23-year tenure as a resident of San Francisco, I also accept that fate, and am thankful for having at least caught a short glimpse of the marvelous city San Francisco once was before being devoured by the mass corporatization of the twenty-first century.