Superradiance, Memo Akten and Katie Hofstadter, Gray Area

Superradiance, Gray Area San Francisco

February 11 through 20, 2026

By Scott Snibbe

Three decades ago, I read a sentence that changed my life: “You are only made of non-you elements.” Without mentioning the Buddhist notion of emptiness, Thich Nhat Hanh led me to an early experience of it—a dizzying, delightful sense that things are not as they seem. Our bodies began with our parents’ coupled sperm and egg; grew exponentially from nine months of mother’s meals, then countless more and millions of breaths taking in molecules of just about every substance on earth.

Our minds, too, he explained, are built from letters, words, and languages we learned from others; concepts, feelings, biases, insights received from everyone else. Ideas I too gleaned elsewhere, including every one included in this review of a phenomenal immersive video installation touching on this truth of interdependence: Superradiance, on view at San Francisco’s Gray Area.

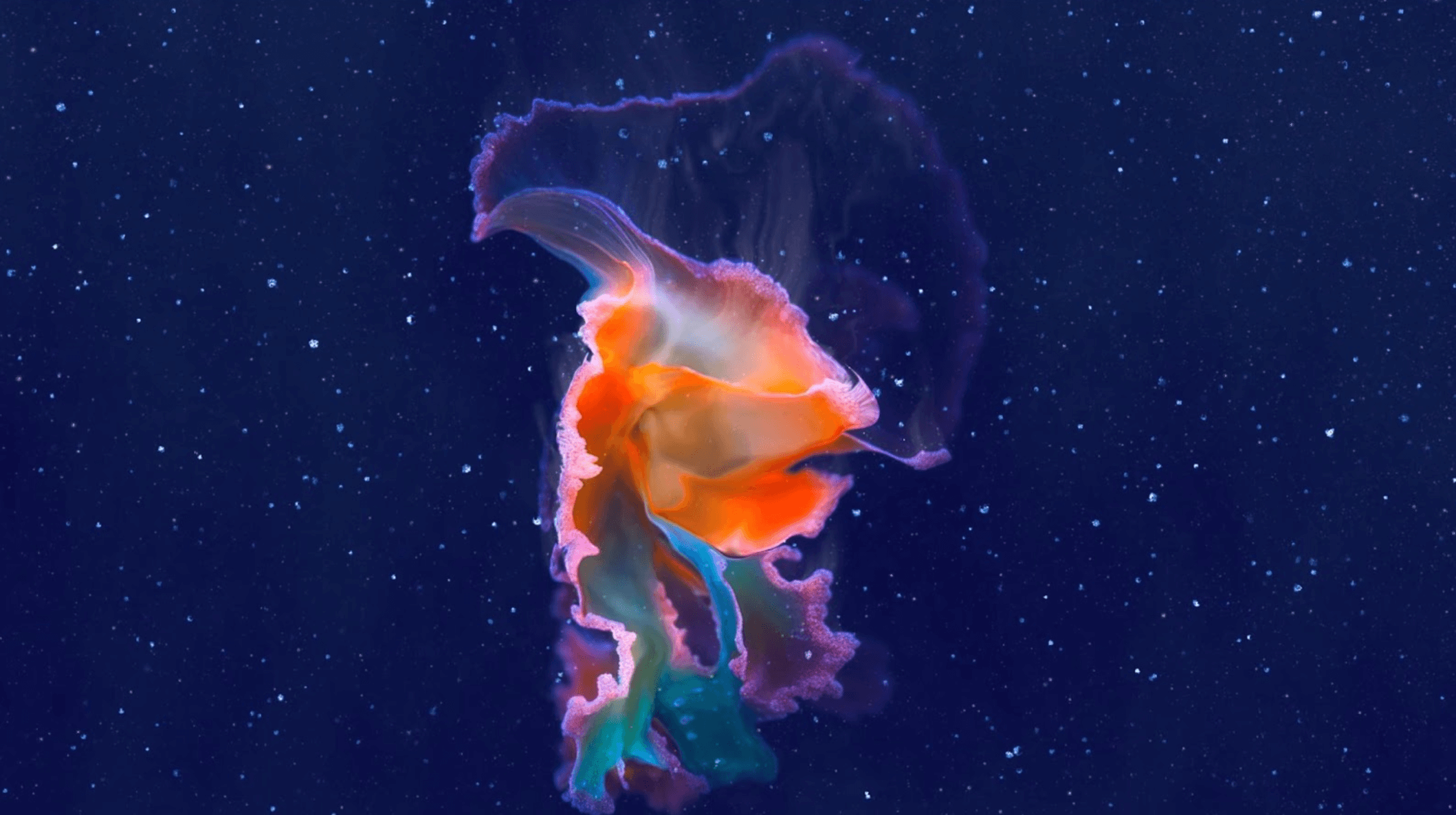

Memo Akten and Katie Hofstadter have produced something profound and rare: imagery none of us have ever seen before. Katie’s dancing body is the centerpiece of this work, which appropriately, we never see. Instead, her liquid movements materialize nebulae, plankton, trees, worms, and mushrooms that seamlessly blend into video backdrops of earth’s beauty. The illustrations to this article prove the illusory nature of the art, because it is only when she moves that we perceive her body. In a still, she appears only as grouped fungi, anenome, and ferns.

Most of us have heard that “we are all made of stardust.” But in this piece, we are rocks, sand, leaves, waves. Literalism can be the bane of good art, but in this case, it’s a literalism that most of us have forgotten and desperately need to restore.

Understanding that we are not separate from the people and world around us is an antidote to the disconnection we feel as individuals, racial and identity groups, political parties, and nations. These conventions serve us at times (and don’t at others), but we are also so much more: part of a magnificent planet from which we emerged and will return.

Activist art also often falls flat, with messages too blunt and obvious for the questions good art provokes. But here too, Superradiance bucks the trend. This is a work of spiritual activism, a call to let go of limiting notions of our past and self-centered projections for our future to bask in the limitless now. This piece doesn’t tell us that we came from stardust, trees, and rain, but that we are these even right now.

An earnest, awestruck (and a bit nerdy) poem accompanies the images, through the voices of its two creators in the present tense:

I am not just the network of the cells within my body. I am also the network of

atoms that I borrow, and exchange with my environment, with other living and nonliving things.

The atoms that I eat and drink; the atoms I inhale and exhale.

Forged in the dying hearts of stars, exploding into supernova, billions of years ago, billions of light years

away, spewed across galaxies to come together — for a very brief moment in time — to momentarily

become me

and you.

These words remind me of the first time I learned of my body’s connection to the earth as a nine-year old boy from an episode of Carl Sagan’s marvelous Cosmos series. Sagan gathered before him a mixture of all the elements comprising the human body: vats of coal, water, chalk, and other elements. Then he playfully mixed them together to see what would happen—of course, nothing much but a bubbling vat of muck. And yet, organized differently, they turn into dinosaurs, octopi, Beethoven.

How do these transform into life? Honorably, just like Sagan, Akten and Hofstadter decline to unpack this inexplicable leap, but lead us to question it for ourselves.

Cosmos, Episode 9, 1980, Carl Sagan

Also included in the exhibition (and on their website, if you miss seeing it in person), is a “making of” documentary explaining how Superradiance was created. At first, I was disappointed in this, wanting the artwork to speak for itself. But when, late in the evening, I finally strolled over to watch it, I was grateful I did. I realized that the notion of emptiness, that everything is interdependent with everything else, extends to this artwork too. It is made of thousands of lines of code, stacked upon centuries of human technological development, filtered through the life experience of its creators. Most tellingly, it employs generative AI technologies in its finishing passes that are responsible for a seamless continuity of body forms with natural environments.

Some may bristle at discovering this, but I urge you to watch the documentary and listen to Memo and Katy’s insights into their process. Early on, Memo teases the public understanding of AI art: most people think all you need to do to make a movie like theirs is to ask, “Computer, make me a beautiful art, very detailed, magical.” The rest of the video then goes on to destroy that illusion.

The artists demonstrate the colossal effort of research, composition, and coding that goes into such a work, while also revealing the late—and yes, magical—pass that stitches together Katy’s movement, thousands of personal and research photos, and the emotion and intention of their work to render the final, beautiful whole. At the moment, I find this piece the greatest example of art created with generative AI I have yet to see.

Fitting within the lineage of experimental animation, Superradiance brings to mind one of its antecedents, the lovely Pas de Deux (1968) by Norman McClaren, a film incorporating the optical printing technologies of its time to extend the movements of dancers into a “long now” impossible to see with human eyes. While many enjoyed its celebration of human movement, some at the time critiqued it for technical virtuosity and unapologetic joy. Don’t make the same mistake when you visit Superradiance.

Pas de Deux, 1968, Norman McClaren

The only critique of the work I might gently voice is the academic language the artists sometimes use to explain it. “A superposition of epistemologies” is a Rubik’s cube of words that many may fail to unpuzzle. But having known Memo’s work from its inception, I understand that it comes honestly from his and Katy’s shared passions for contemporary art theory, scientific inquiry, and technological critique.

I urge you to enjoy this extraordinary work that resets our sense of place on earth, in nature, and among the mysteries of the universe. If you can, visit in person while it’s here in San Francisco to experience it with your own body (and friends’). If not, tonight, dim the lights, send this video to the largest screen in your house, and enjoy a work of art astonishingly new and beautiful that connects you to your deepest, ancient roots.