We Should Be Talking About John McKie’s Art

Many people never heard his name. Most never saw his drawings, those quick, deft little worlds he scratched into cardboard, paper scraps, and whatever surfaces his hands could find. But John McKie was the type of artist whose work makes you stop mid-scroll, mid-thought, mid-breath. You look once, then twice, then you look again. And that is the mark of someone who saw life clearly. Painfully clearly. Tenderly clearly.

So who the hell was John McKie?

He was a man who made things because making things was his way of being alive. A quiet worker. A relentless observer. Someone who understood that art is not always a grand gesture. It is often a modest one, repeated daily with devotion. McKie was never the artist vying for attention. He didn’t wrap himself in theory or credentials. He didn’t use prestige as a shield. He simply made work, steadily, sincerely, without fanfare.

John McKie was born in 1960 in the north of England, close to the Scottish border. He worked ordinary jobs and even ran a traditional business for years, a life that he says never quite fit. Eventually he turned toward drawing with full commitment, deciding to make art every day, often on found materials and discarded packaging. A steady online audience and collectors who recognized the rare clarity of his vision sustained his practice and ultimately helped springboard exhibitions in London, Berlin, Copenhagen, Ireland, Vienna, and the United States. The size and stature of those exhibitions is not clear, with not a lot of precise information available regarding them.

His career was not without reach. It simply unfolded without institutional noise, in the independent and self-propelled way his life seemed always to insist upon. He is survived by his wife, children and grandchildren, who knew him first as a person before the rest of us came to know him through his work.

John McKie with his beloved wife, Sarah McKie, courtesy of Sarah McKie’s Instagram.

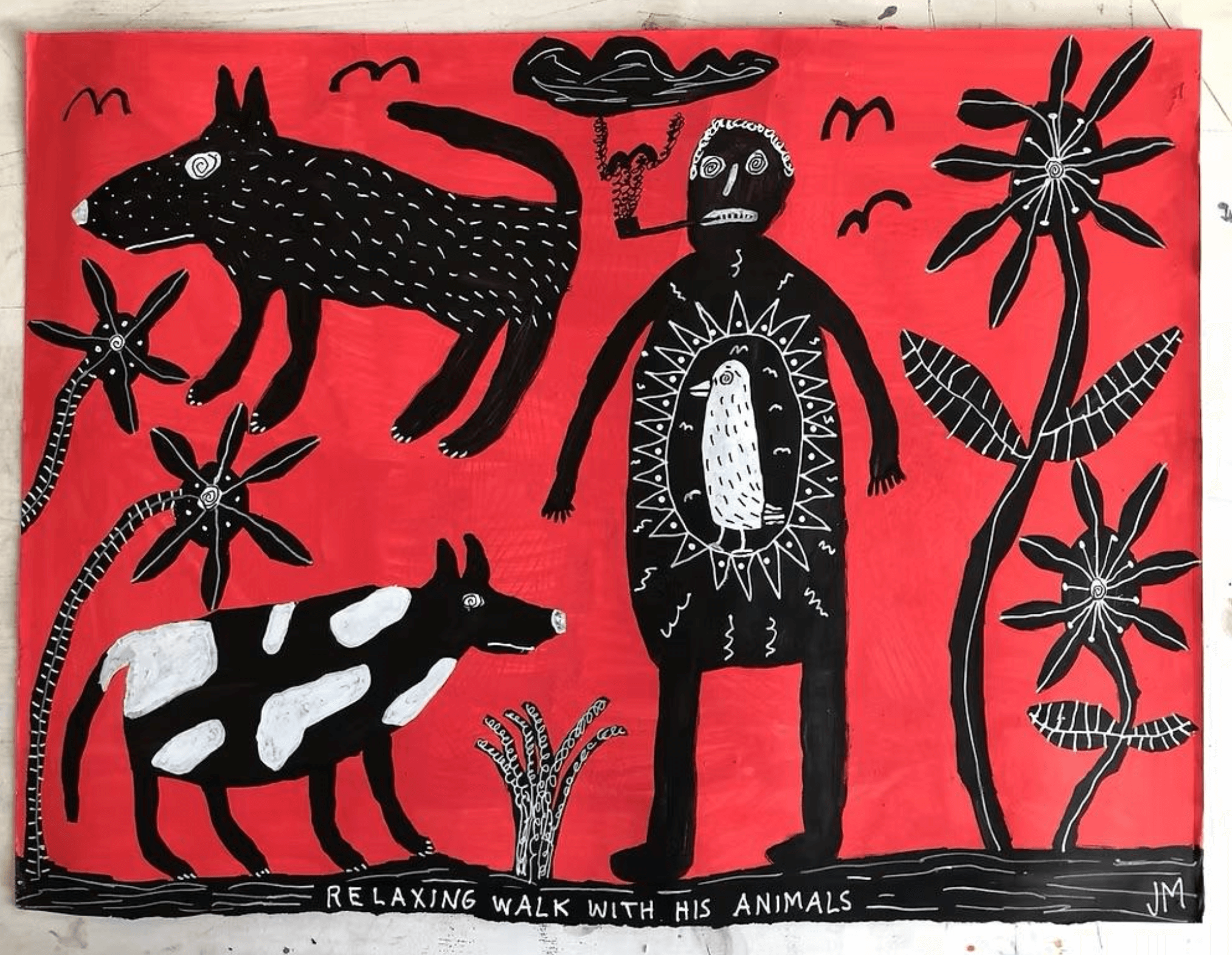

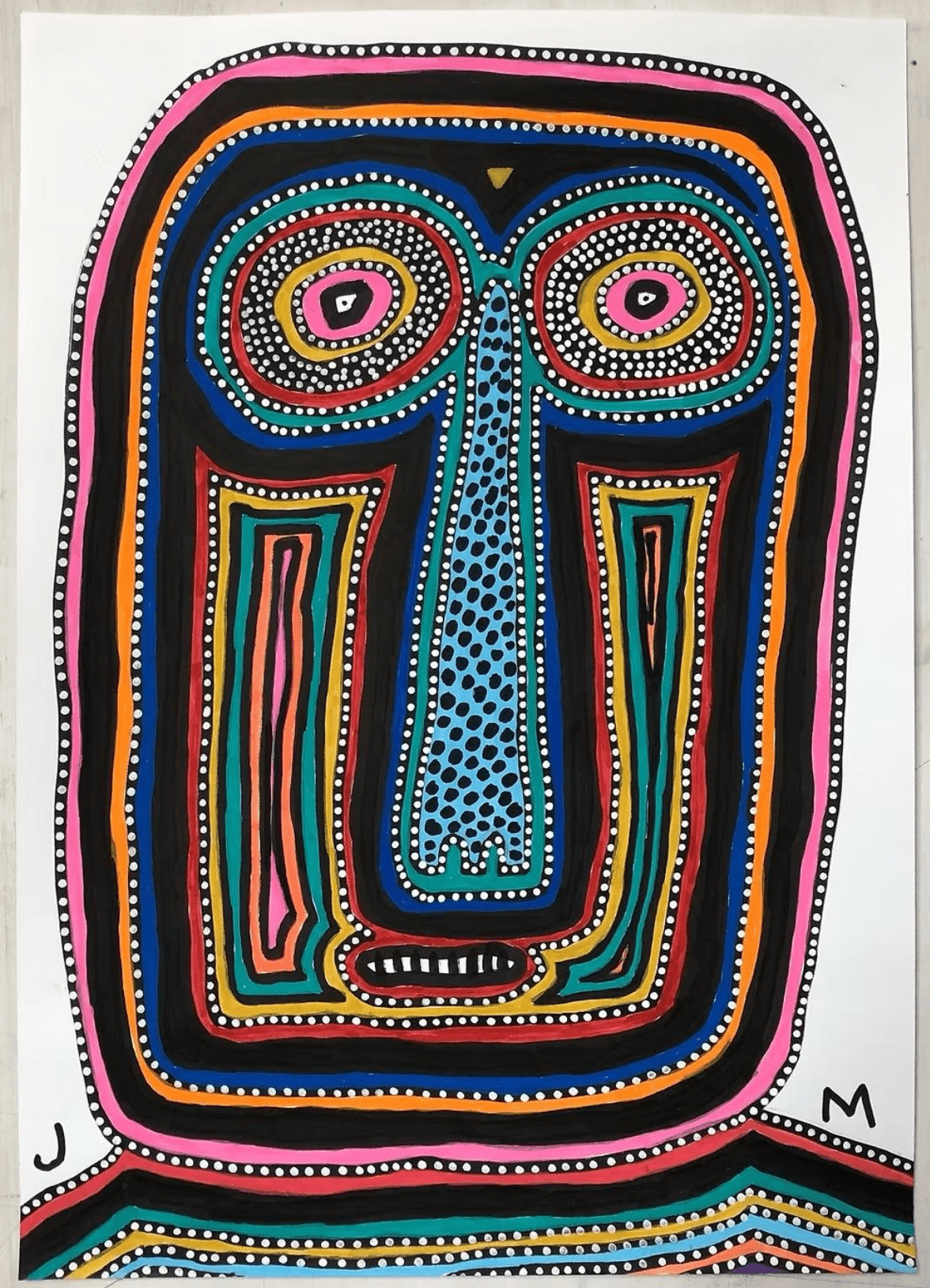

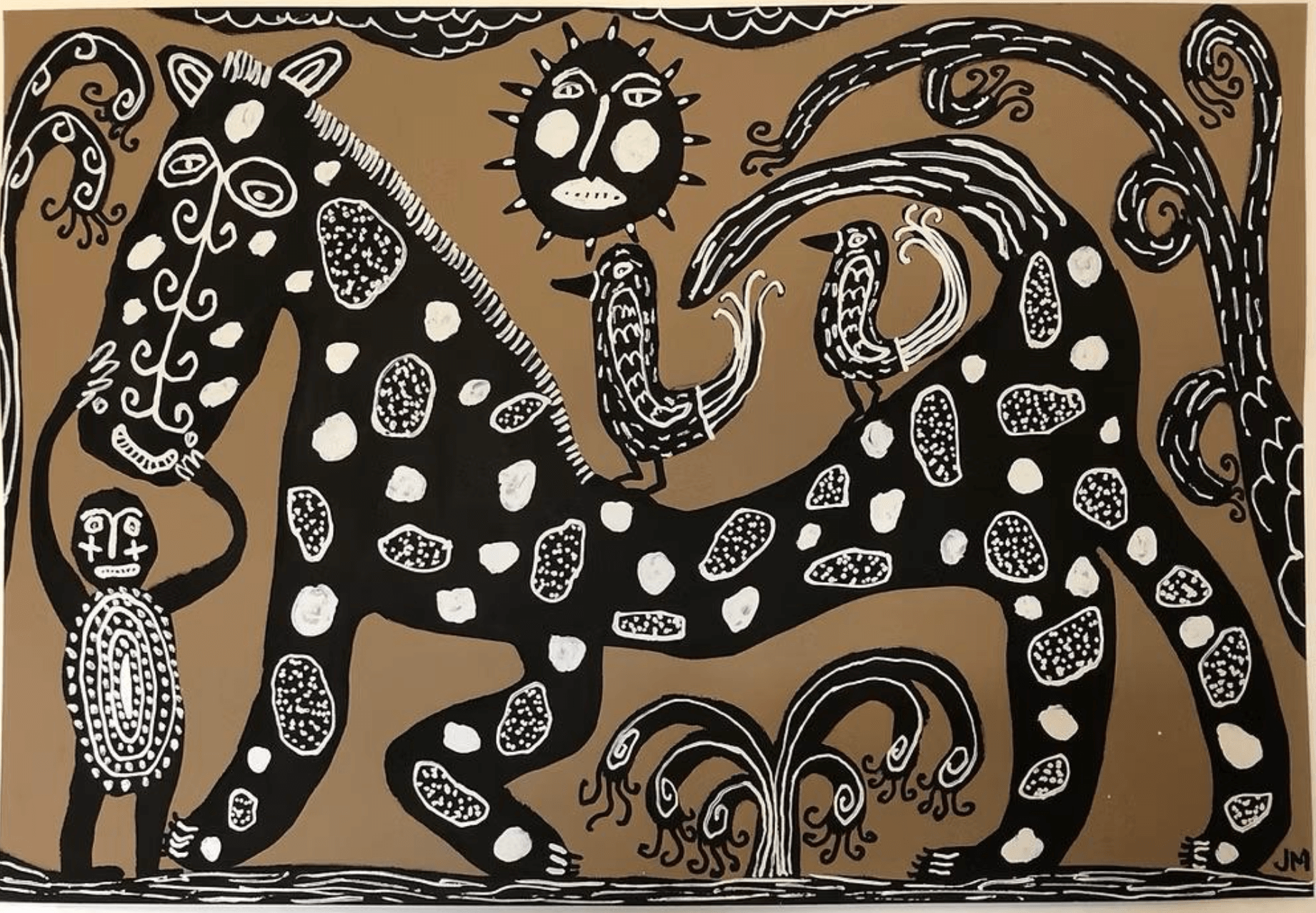

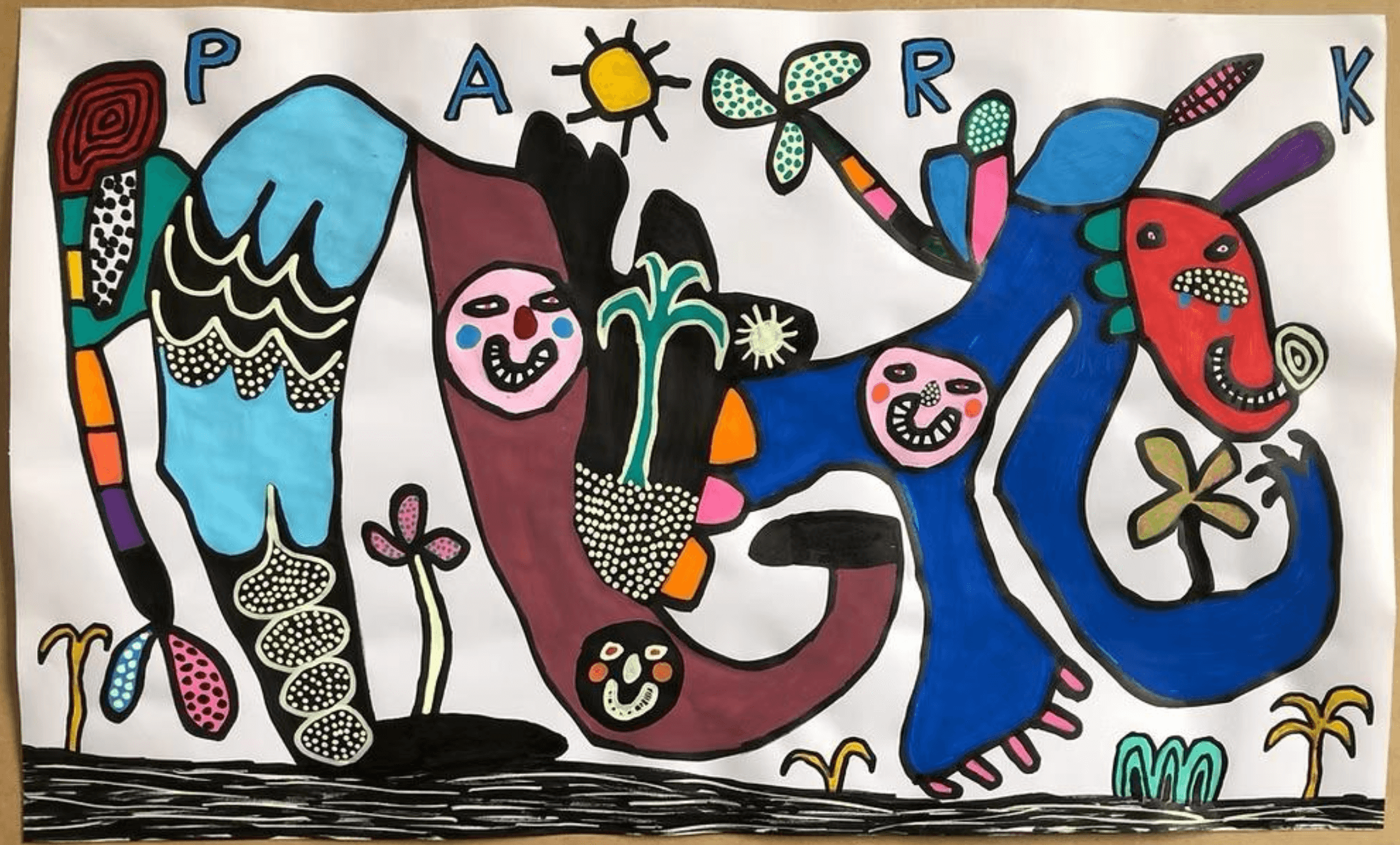

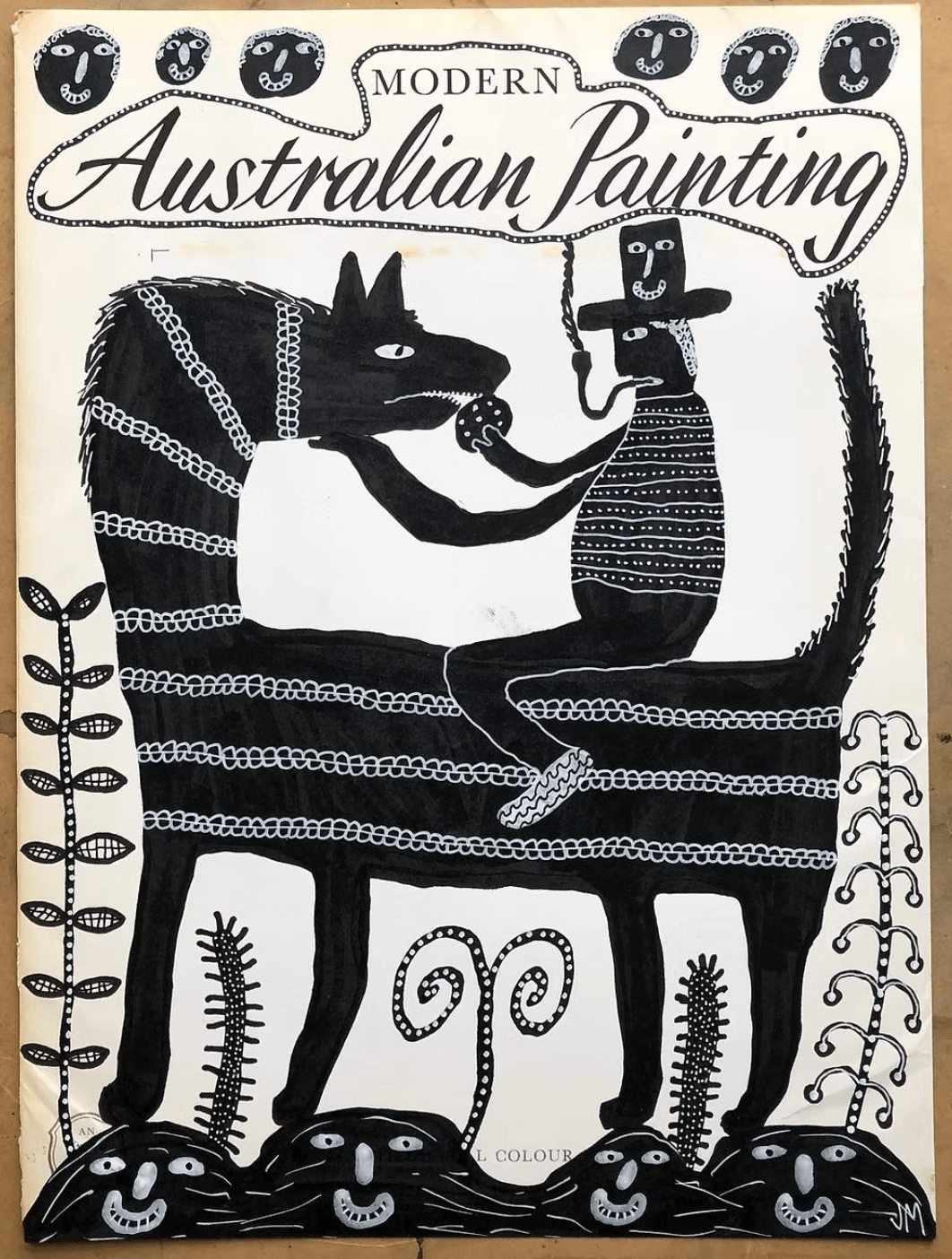

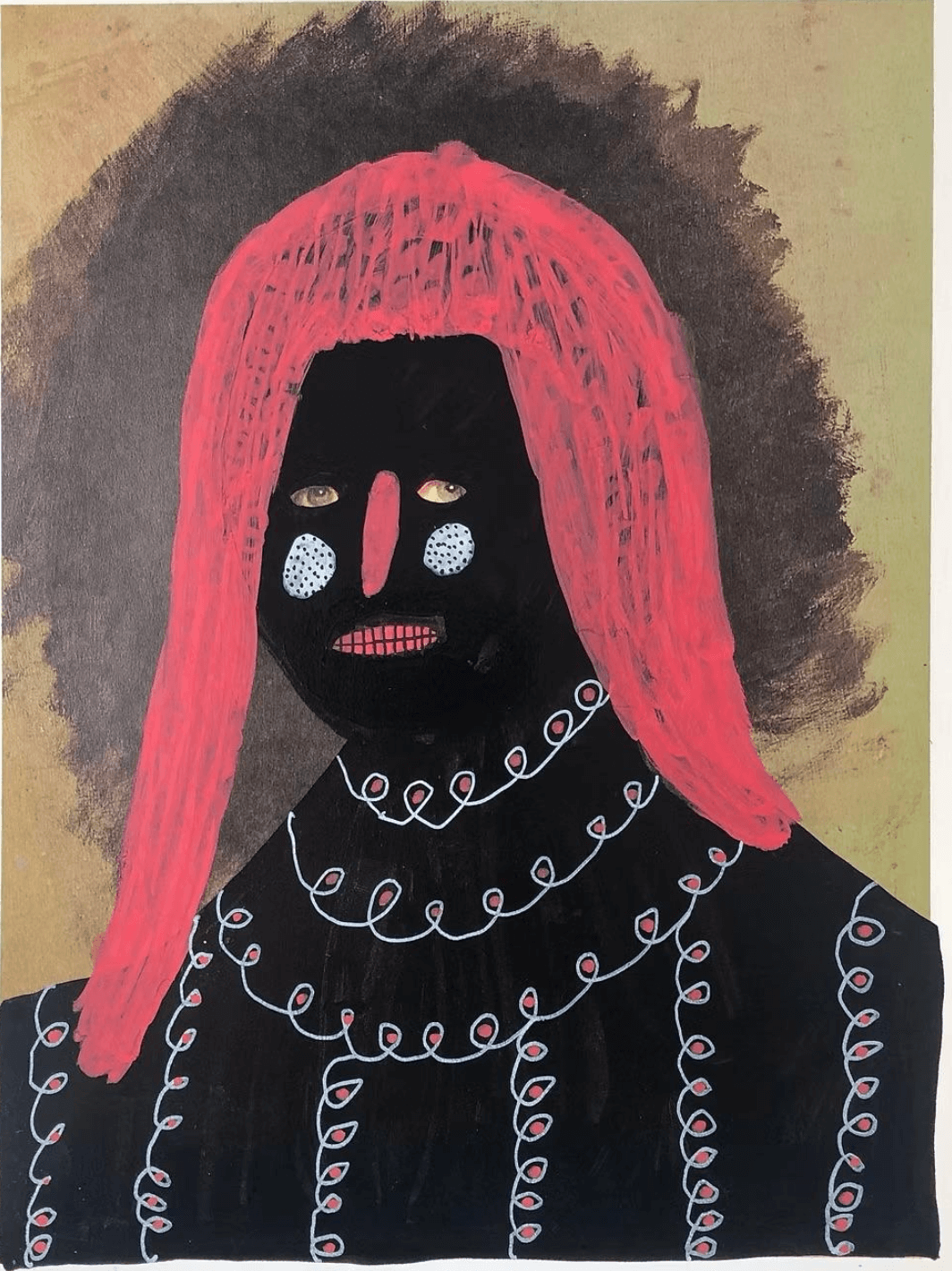

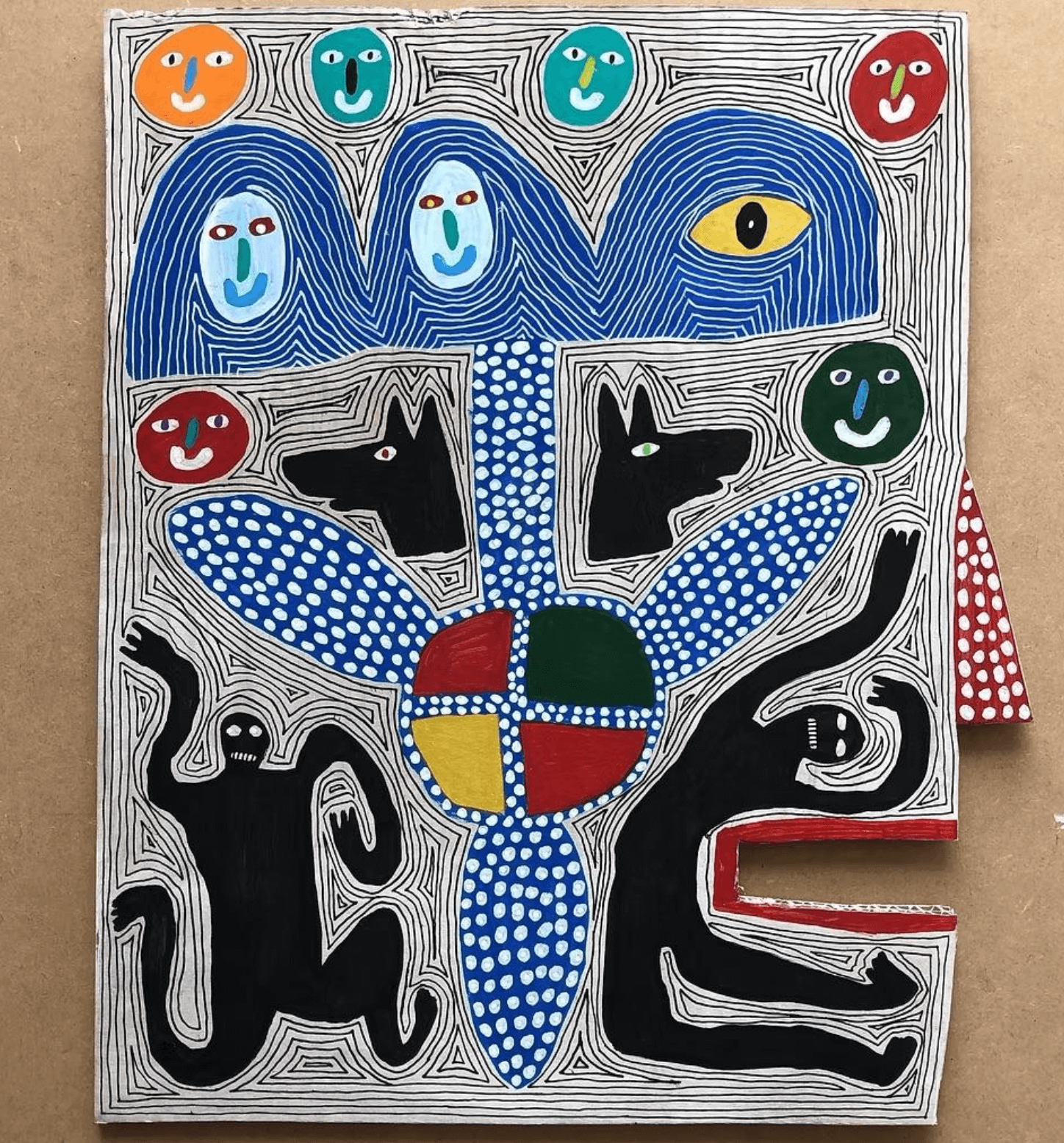

And in doing so, he created one of the most distinct and deeply human visual languages of any folk-leaning or self-taught artist in recent memory. His drawings, often built with humble materials like pens, markers, and flattened boxes, possess an astonishing clarity of character and form. At first glance they appear playful, almost naïve. Look longer and you discover an eye trained like a razor on gesture, posture, tension, and emotion. Nothing extraneous. Nothing decorative. Everything necessary.

Though McKie worked quietly, his place in the broader story of drawing is unmistakable. His instinctive, unpolished style shares a certain kinship with the raw immediacy of Jean Dubuffet, who believed that creativity exists most vividly outside academic walls. There is an echo, too, of the directness found in Bill Traylor, that ability to express entire worlds with a few decisive lines. Beneath the humor in McKie’s figures lies something akin to the late work of Philip Guston, where cartoon clarity meets emotional depth. These connections do not box McKie in. Instead they affirm what his drawings already prove. His hand belonged in the company of artists who saw the world askew in the most revealing way.

McKie’s work also reminds us how thin the line can be between what is called naïve or outsider or folk art and what is placed inside the category of fine art. Labels can be useful, but they are often lazy. What makes a drawing resonate is not its agreement with a category but its ability to surpass mere scribble and become thought, feeling, and perception made visible. McKie’s drawings do exactly that. They hold their own in the same room as so-called fine artists because they are built from the same essential ingredients: clarity of seeing, decisiveness of line, and the courage to say only what matters. But, it is a rare occurrence for folk artists to be recognized with the same stature and reverence that we see with artists formally embraced by the fine-art canon.

McKie’s figures feel as though they are only seconds away from moving. His lines are decisive, but never stiff. His compositions hold the peculiar balance of humor and melancholy that only the most perceptive artists ever reach. There is wit without cruelty. Simplicity without emptiness. Directness without bluntness.

This was a man who saw people.

Not as symbols, not as archetypes, not as clichés, but as oddly proportioned, expressive, crooked, charming creatures full of longing, awkwardness, and grace. His drawings capture that essence with startling accuracy. The fact that much of his best work was made on whatever he had around, cardboard, scrap paper, envelopes, only heightens the miracle. He proved, again and again, that great art doesn’t come from expensive materials. It comes from the eye that looks and the hand that responds.

For years, his output existed both quietly and widely, traveling further than the noise around it ever did. It appeared online, in small shows and international exhibitions, in the homes of private collectors, and in the hands of people who understood immediately what they were seeing. Yet even with that reach, his name never circulated with the volume or reverence his work warranted. That gap says less about him than it does about the art world’s blindness to artists who refuse spectacle and simply do the work.

When he passed away last year, the broader art world barely noticed. Maybe that is the clearest indicator of how the art world sometimes fails its most gifted contributors. It fails the ones who are not loud or strategic or institutionally framed. The ones whose work slips through the cracks until someone finally stops and says, “Wait. This is extraordinary.”

John McKie was extraordinary.

Not because he chased innovation, but because he embodied it without ever needing to say so. Not because he built a public persona, but because he let his work speak for him with astonishing authority. His drawings hold the kind of compositional intelligence that schools try, and often fail, to teach. His sense of line rivals the great illustrators. His ability to distill the soul of a figure into a handful of strokes feels nearly impossible to replicate.

There is nothing “amateur” about his output. There is nothing “small.” The humility of the materials and the modesty of his personal presence should not mislead anyone. His legacy is large. His work deserves to be seen, studied, collected, and written about. It should sit in conversation with other visionary draughtsmen. It belongs in exhibitions, archives, and in the homes of people who understand what they are looking at.

This piece is not an obituary. It is a doorway.

It is an invitation for the wider art community to finally step into the universe John McKie built, line by line, figure by figure, cardboard by cardboard. It honors a man who gave us a body of work overflowing with compassion, humor, odd beauty, and unmistakable skill. It recognizes that some of the most important artists are the ones who never shout, never demand, never brand themselves, but simply make the world more bearable with every image they leave behind.

If you have not encountered his work before now, consider this your introduction.

Look closely.

Look patiently.

Look with the same generosity he offered to every figure he drew.

Because now that he is gone, the responsibility of noticing him, of truly seeing him, belongs to us.