Francesca Wilmott, Sara Morris, Curators at the Crocker Art Museum

Francesca Wilmott is a Curator at the Crocker Art Museum, where she is responsible for the Museum’s collections of post-war and contemporary art as well as photography. She holds a Ph.D. in art history from The Courtauld Institute of Art in London. Wilmott's writing has appeared in Artforum magazine, A World History of Women Photographers, Marcel Broodthaers: A Retrospective, and Yoko Ono: One Woman Show, among other publications. She is currently organizing the career retrospective of Gladys Nilsson, which will open at the Crocker in summer 2026, and is co-curating the Crocker's 2028 exhibition Black Artists in California with Unity Lewis.

Sara Morris is the Ruth Rippon Curator of Ceramics at the Crocker Art Museum, where she oversees its collection of historic and contemporary ceramics, as well as its craft and decorative arts collections. She is a PhD candidate in art history with a doctoral emphasis in Feminist Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara, where her research focuses on craft and material culture of the United States. Her writing has appeared in Ceramics: Art and Perception, The Journal of Modern Craft, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art, and the Archives of American Art Journal.

The following are excerpts from Francesca Wilmott and Sara Morris's interview.

Hugh Leeman: Sara, I want to start with your research, it traces how figurative ceramic sculpture uses the body narrative imagery, hand making and community to convey identity. How does that scholarly lens feed into how you read objects even beyond ceramics? For this exhibition at the Crocker Museum? Making moves.

Sara Morris: Oh, wow. So first of all, I guess I got to go all the way back. I'm pursuing my doctoral studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara, where I've taken feminist art history courses in both the art history department as well as the feminist studies department. And it was through the real privilege of learning from my professors and from reading so much feminist theory, from so many brilliant thinkers and having time to sit with their ideas. Um, in which I was kind of able to think about how feminism is really a lens or a series of perspectives with which to understand the world and with which to understand, um, power and oppression. And so I think in my dissertation, this really comes up through the artists that I decided to write on, which are three women artists based on the West Coast. Granted, I was writing my prospectus during twenty twenty, so my travel was very limited, and at the time I had to think, what archives can I foreseeably drive to if this pandemic were to last another two or three years? so my focus was on the West Coast, but I would say that in my dissertation and in all of my curatorial projects, the stories that I'm telling, as well as the artworks that I decide to include in in my stories, are really influenced by feminism and through craft. I tend to write about artists who are drawing on material or cultural cultural traditions that are really rooted in, ways of making that have to do with women's work or associated with craft. So ways of making that have historically been overlooked or undervalued because of their associations with femininity. I think that in so many ways, my dissertation on figurative ceramics on the West Coast has really inspired everything that I do since.

HL : You bring up this really interesting point mentioning, studio craft, and I want to pull Francesca into the conversation here because. Previously, Francesca, you've spoken about studio craft as being, quote, often overlooked and canonical narratives. What do you think museums need to change practically and philosophically to stop reproducing those hierarchies?

Francesca Wilmott: Yeah, I think the the word you use hierarchies is exactly the point. It's there are so many hierarchies that exist within the broader art world, and those we see in museums as well, and museums like the Crocker. We're really trying to break down these hierarchies between, you know, so-called fine art and craft or functional art. and I think that it takes coming together with your colleagues and, sharing expertise across our different areas of discipline. I mean, even thinking about our training. And I don't want to date myself too much, but I, you know, I studied art history first in the early two thousand, and there was very much a division still between craft, decorative art, functional art and fine art. And it's important as a curator to stay abreast of scholarly discourse, of the ways that artists are thinking and making. Because most artists are not really working within these silos. Some are. And that can be really productive as well. Um, but I think it's really about collaboration. That's a key part of it. Um, as well as staying critically informed about the larger discourse.

SM: I would just add that, you know, as curators, sometimes we feel siloed. You know, we feel siloed by these art categories, these hierarchies, our collections that we are in charge of, or the galleries in which we show the work in. And so I really feel like through an exhibition, like making moves, we're able to work together and to learn from one another and to see why or how there are so many more similarities than differences between the artworks that we're working on and the artists that we're interested in.

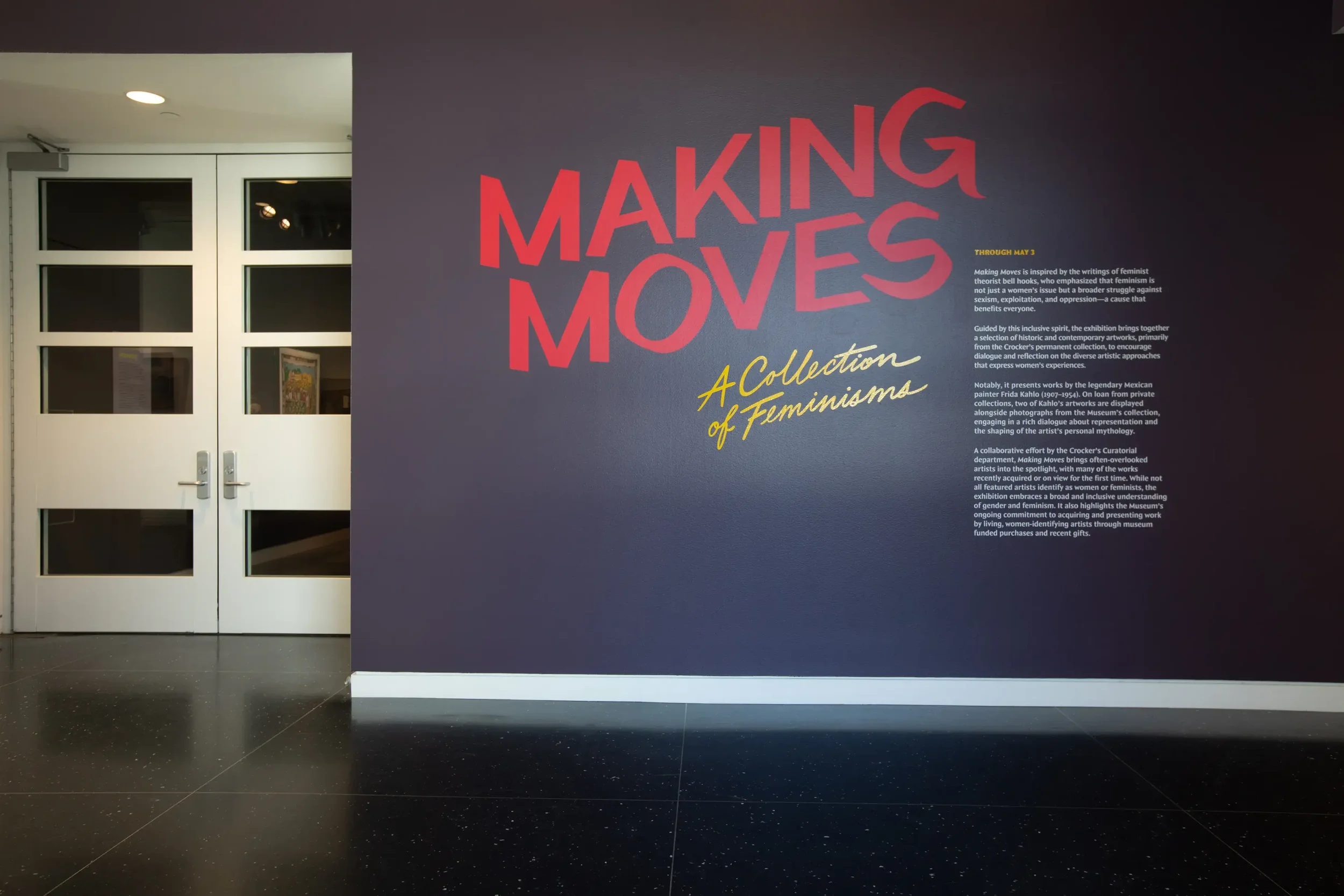

HL: Thank you. Thank you for adding that. I want to pull on that thread a little bit further because it's very interesting. And earlier, Sara, you mentioned feminism and the way that informs your curatorial practice. So the exhibition Making Moves is inspired in no small part by bell hooks insistence that feminism isn't simply a women's issue, but it's a broader struggle to end sexism, exploitation, and oppression. How did this framing shape your curatorial decisions, from artist selection to interpretive voice?

FW: Yeah, Bell hooks was present, as you said from the very beginning. Um, we both have read and engaged with bell hooks for many years, and this idea of an inclusive plural Feminism was the driving force behind the show. As you know, the title is Feminism's Not Just a Singular Feminism. And so we were thinking about it in very literal terms in that it's not just women in the show. There's also male artists and non-binary artists. Um, and we're also thinking about it in terms of the diversity of women's experiences.

SM: Yeah. I think what this show demonstrates and does really well is what Francesca was saying. There is no one female perspective out there. And in fact, feminism takes so many different forms, not only now in contemporary art, but across time. Um, and so we're really seeing the many different forms that feminism or feminisms takes in visual art especially.

FW: Yeah. So we use the term pretty broadly in the exhibition feminism, you know, as we think about it and as we know it, today was not a term that many artists were using at the time that they were making the works in the show. For example, we have an oil on canvas painting by Angelica Kauffman of the singer Sarah Bates from seventeen eighty, and that predates feminism as we know it by many centuries.

SM: Yeah.

HL: Well, I want to zoom out on the exhibition as a whole because of what you've just said. It brings up this very interesting point about making moves is it's drawing primarily from two centuries of the Crocker Art museum's acquisitions. With that idea in mind. What did the museum's collection itself over those two centuries of acquisitions tell you about different feminisms over the generations, and what are some of the gaps and silences in the holdings that you wanted the exhibition to make visible?

SM: Oh my gosh, that's a huge question. And it's one that we've been thinking about and trying to answer for two years. I think that it was the Crocker's institutional history, the founding of the institution by Miss Margaret Crocker, which served as the real inspiration for the exhibition. Um, you know, when visitors come to the Crocker and they enter the historic building and they see the double grand staircase and these really colorful tile floors, they might miss this marble plaque on the wall that says that, um, the museum, the building, as well as it as well as its treasures, was gifted by Margaret Crocker to the city of Sacramento in eighteen eighty five. And at the time, our collection had European and American paintings in it. Um, and it was this gift of the building and its art collection, which makes the Crocker, I believe, the very earliest public art gallery in California, if not the West. And this is the institutional history that we've inherited, as well as like, you know, centuries of our predecessors and brilliant colleagues adding to the collection. And I would say a huge source of inspiration for the show was the many different women who have been a part of the museum, who have helped shape the collection and the museum sense.

FW: So yeah, so it doesn't end with Margaret Crocker, but she had many daughters who were really influential as well. And we have a case dedicated to the daughters and photographs of them. Um, and that's within the memory, uh, subsection of the exhibition. Uh, but one of the daughters I might highlight is Jennie Crocker Fassett. And she helped raise money to purchase the mansion building of the Crocker and reunite it with the gallery in the early nineteen hundreds. because those two parcels were then split, and so she helped change the foundation of the museum. But she also acquired some of the first Asian artworks in the collection, as well as founding the ceramics collection. so in nineteen twenty five.

SM: So this year would mark one hundred years of the ceramics collection.

FW: So very forward thinking and very dedicated to their philanthropy. Um, and we've seen through the years how their legacies have been honored in different ways. So one thing I know we both really love about the Crocker's history is that the museum has taken risks in giving career retrospectives to women artists, and that goes way back. But Ruth Rippon was nineteen.

SM: Oh, well, I mean, even my position as the curator of ceramics here at the Crocker speaks to the importance of the artist Ruth Rippon and her legacy to the institution. My position was founded through the generous support of the late Anne and Malcolm McHenry, um, in honor of Ruth Ripon and kind of her shaping of, uh, ceramics as a discipline for art in Northern California. And so she did have a retrospective exhibition. But not only that, she was so instrumental in bringing different retrospectives, organizing, organizing exhibitions here at the Crocker when she was alive, as well as, um, adding work to the collection.

FW: Yeah, so very multifaceted. And, um, the legacy continues today. Um, just a plug, a future exhibition that I'm working on, um, in summer twenty twenty six. So about six or seven months from now, um, I am organizing Gladys Nelson's first career retrospective, and she's a, an artist who is most often associated with Chicago. But she lived in Sacramento between nineteen sixty eight and nineteen seventy six, and the Crocker actually gave her her first solo museum show in nineteen sixty nine. Even though the Whitney is often cited as her first solo show in nineteen seventy three. Um, and so we are honoring and really nodding to that long career. And, um, the fact that Gladys is not just a Chicago artist, but she is an artist in her own right, no geographic identifiers needed. Um, and that will be her first career survey this summer.

HL: It's impressive to hear this backstory. And, you know, from the way that you frame this, there's this incredible you might even call it the vanguard of putting these issues in front of the public and giving opportunity for people to to discuss this either either publicly and creating discourse or in a more private sense, in their own homes and in the privacy of their own minds. I think art has an incredible power to do, if that gives us a bit of a backdrop historically for the museum, if we come back into something more specifically to to your exhibition of making moves. This show invites viewers into themes like self-representation, memory, care, and the erotic. When you were building the exhibition's internal logic, what were the conversations like that landed upon these themes?

FW: Yeah, I wish we could.

SM: Internal logic.

FW: Yeah, I wish we could show you our dry erase board because the themes evolved over time. And I would say what we did to begin with was we made a list of all of the women, women identifying artists and another artist, um, in the collection who were exploring women's experiences, who we felt like had to be in this show. And as we kind of winnowed that list, it, you know, sometimes it grew, sometimes it shrunk. Uh, the themes naturally emerged. There really was not like a didactic approach to it. Uh, we allowed the artwork to guide us every step of the way.

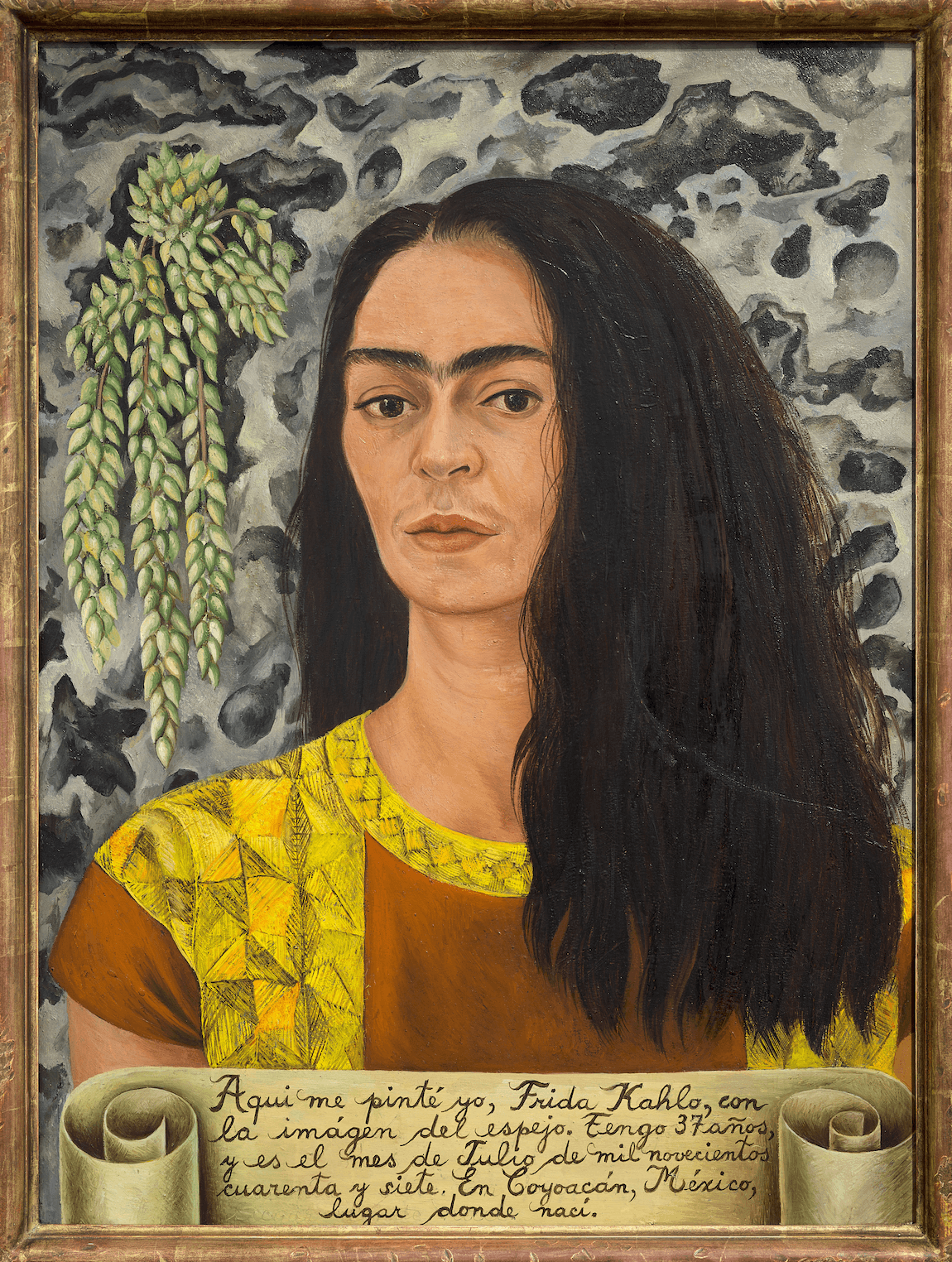

HL: With the idea of the artwork guiding the steps along the way. So one of the works that's not a part of the collection, that is a part of the exhibition, and of course, is really one of the hero images on the website and so on, is Frida Kahlo's Self-Portrait with Loose Hair. It's on loan to the museum. It's shown alongside Kahlo photographs from the museum's collection. How are you thinking about storytelling around Frida Kahlo in this in this exhibit? And what do you want her presence to address in the exhibition's larger ideas that we've just mentioned?

SM: Well, Frida Kahlo is kind of a branch. Um, she has her own gallery, including the photographs that you mentioned and she kind of branches off of or is a continuation of the gallery in which we explore the representation of women by women. Um, and so it's a lot of portraits of, um, of women by women artists or Are self-portraits. Um, and so you kind of turn a corner and you see Frida Kahlo's self-portrait there, and it's just really it's a really stunning sight line in the show, and we're so happy to have it in the exhibition.

FW: Yeah. And I think the self-portrait picks up on themes and helps extend themes that, as you were saying, are already present in the exhibition. And so within this really stunning self-portrait from nineteen forty seven, we see Frida Kahlo with her hair loose, kind of cascading over her shoulders, and she looks weary. It's not like this done up, Frida, that we all know and love. Um, with embellishments in her hair, but she looks really natural and very kind of tired, for lack of a better word. Um, and we learned as we were putting together this section of the show that she had had spinal surgery just shortly before she painted the self-portrait. And she called this period at the beginning of the end in her career. And she passed away not too long after that, about, I think, about seven years later. Um, and so she painted the self-portrait, as she says in the inscription while looking in a mirror. And so it's this really candid self-portrait that, of course, does have a lot of self-mythologizing. That's part of her work as well. And Frida Kahlo was known for often representing herself in mirrors or using mirrors as a kind of surrealistic device in her work. And within the photographs in this section of the show, we see Frida looking into a mirror, in this mirror, in this beautiful photograph by Lola Alvarez. Bravo, Bravo! And then we also see a photograph of, um, Emmy Lou Packard of Pre-dose belongings in her vanity mirror. And so there's this, um, mirrors. They show up throughout the entire exhibition. Really?

SM: And what's great about this section? Um, it really turned out quite well, I think, because it speaks to Frida's larger artistic circle and the friendships she made, especially with women during her lifetime, who are themselves trailblazers and really notable figures within their own fields. Um, Emmy Lou Packard being one. And so people, I hope you know, will come to the exhibition to see the Frida. But in doing so, they'll also learn a little bit about artists like Lola Alvarez Bravo and Emmy Lou Packard. Um, and Dora de Larios, who is a ceramic artist, also kind of in the same gallery space.

HL: I want to pull that idea of a past generation so that Frida, of course, represents and that she's got her own section there and then pull this into a contemporary realm. Can you talk about how contemporary artists that are in this exhibition are addressing issues around feminisms in comparison to past generations, artists such as Frida or others that you've mentioned?

FW: One of my favorite sightlines in the exhibition is when you're standing in the care section of the exhibition, and in the foreground is this really stunning painting by Rupi C tut, and she's a Bay area artist. She grew up, um, in India, and she immigrated to to the United States. And a lot of her work is exploring migration and diaspora and family stories and narratives. And in the background is the Frida Kahlo that we just discussed. And the works together just form this really striking dialogue between the past and the present, between different geographies. and also ideas of self-representation and care. So even though the Frida Kahlo is not in the care section of the exhibition, it certainly is. she's thinking about her ailing body and self-care in ways that she probably didn't, you know, have the same language that we use to explore it today.

SM: What I really like about this question is you're getting at something that we really strove to do within the display, that we created with within the layout of the show. And what we wanted to do was kind of create these unexpected and surprising pairings between both historic and contemporary works in order to draw out larger themes and ideas. And most of the time, these kind of came to us when we were looking at the artworks together and we're like, wow, you know, even though there's a hundred years separating this Mary Cassatt and this Wendy Red star. They're both thinking about themes of motherhood and care. Um, one of my favorite pairings in the exhibition is also in the care section, and we have this, like, exquisitely beaded dyak baby carrier that was made in Borneo, Indonesia. And these took many months to create. They were usually begun once a woman found out she was pregnant and created by many members of the family. Um, people would kind of collaborate and contribute to the piece by bringing like, say, animal teeth or shells or other beads to the piece. And so it's it's beaded from these very, very tiny seed beads. And it has this motif on the front that has like faces and flowers on it. And it just is so beautiful. And I can't believe it's made to carry a baby. Um, and then you see next to it we have this small intimate painting by an artist, page Jiyoung moon. That's right. And it's called Three Generations. And it's this painting of a bedroom. And in the bedroom we see a baby, a mother and a grandmother all kind of laying on this floor mattress, and they're surrounded by their belongings. They're surrounded by, um, like a stuffed animals. They're surrounded by clothing, everyday objects that kind of speak to the labor of caretaking and child rearing and motherhood. And yeah, so I think that, you know, there are plenty of these little surprises to be found in the exhibition.

FW: Yeah. And as you're describing that combination, I feel like these works continue to open up new meanings for us. Page Jiyoung moon painted that the first time that she took her young daughter back to her native Korea to experience her homeland and meet her side of the family, and the painting was done in, I believe it was a hotel room or some kind of temporary dwelling while they were traveling South Korea together and thinking about that in relation to the baby carrier and this idea of motion and transit, um, that is also really poetically resonant as well. Um, so it's a lot of fun to visit the to visit the show and just see what new meanings might come up for you.

HL: In a minute here. I want to turn our attention towards some of the programming, because you've created an incredible robustly of programming for this. But before we do, I want to. What you both have just mentioned on here is a very interesting idea, because it can be easy to visualize oftentimes that an exhibition is a lot of figurative work, especially with some of the themes that we're talking about here. But then the piece that you've just mentioned, clearly, it's not that, and pulling this into that larger conversation that these pieces are sparking, making moves spans the figurative and abstract expressive approaches. How do you think abstraction speaks to lived experience differently than the figurative works in this exhibition?

SM: Oh, I could talk about this one. And you can. We have so many thoughts about abstraction, um, in regard to this exhibition. And I think it pops up in a few different areas in the exhibition. One of my favorite in the section on the erotic, which we're calling Reclaiming the Erotic in part, there's a lot of work that is figurative, and they're using more like, um, like humor as a strategy to kind of unpack the erotic in art, um, as a genre that has historically been dominated by men. And in the other part of the gallery, there are plenty of kind of semi-figurative abstract works. One in particular that we were very excited to include is a large abstract painting by Joan moment, and I believe it's called Heavenly Body. Um, and. And an assemblage of notables. And it's, um, a painting in which you see all of these pinkish purple or, or discs kind of floating or orbiting around one another. And in looking at the title, you're like Heavenly Body. Perhaps this is some kind of abstract celestial imagery. We're looking at the cosmos. Um, there's a a million different ways you can kind of read the imagery and the colors and the composition. It's very harmonious. It's very beautiful. There's a lot of rhythm to the piece. Um, but we display it next to a preparatory work by Judy Chicago that she made, um, to prepare for her monumental feminist installation, The Dinner Party, which is really known for these beautifully China painted plates and table settings that each honor a notable woman from history. And each of these plates famously has kind of vaginal iconography, which is very colorful and very abstract. And so when you see the Judy Chicago plate next to Joan moment, all of a sudden these celestial discs or orbs tend to take on a semi-figurative general or genital. They look a bit more representational than they did at first.

FW: Yeah, and Sarah and I did many, many studio visits leading up to this exhibition, and we met with Joan Moment in her studio in Sacramento last year. And we learned that what might be just seen as an abstraction with the heavenly bodies does have strong ties to erotic imagery. Um, around just a few years before she painted that piece. She made this large panel that she just covered with condoms. Um, and they become this kind of Agnes Martin esque, um, geometric, repeated pattern. But it's condoms. Um, and so she's, um, Joan moment is certainly exploring these ideas. Um, and I think her work can be approached from many different angles in that way. Um, but another section of the exhibition that is exploring abstraction is one of we have two sections on memory, and the section on material memory is looking at how artists, women artists, primarily have used their body to make these large scale abstractions. Uh, there's a large print by the Korean artist Kyung Soo, who lives here in Sacramento. Um, and she is both using her body to do the mark making, uh, But she's also interested in this alchemical mix between, um, different, like water and shellac, for example. And, um, that is next to a fireplace screen by Nancy Jen, who is a notable, um, abstract expressionist, uh, Bay area abstract expressionist who was, uh, just kind of getting her due. Now, she recently had a retrospective at the Sonoma Valley Museum of Art, and together, I think those two works and the way that the body is this index for identity, as well as for movement and abstraction and memory, um, they really play out and play upon each other really nicely.

SM: It's really fun how the body seems to kind of linger below the surface in this part of the exhibition, and then surface either through like materials or processes after you learn a little bit more about the piece.

FW: Yeah.

HL: What's particularly impressive about what you've done beyond the exhibition is there's all of this programming for making moves and you've got performances, conversations going on. And this is since the opening. I'm curious about how can museums, the Crocker itself, and other museums across the country, around the world, begin to incorporate some of what you're doing here in this idea that programming becomes more central, as opposed to a peripheral add on, so that it becomes core to museums role in society. And it's so much societal change and institutional challenges.

SM: It helps to have a really amazing education department. I must say, our colleagues in the education department are incredible, and they are sources of inspiration for us, and they're always feeding us, um, different ideas and things that they would like to do. And sometimes it's a lot. Yeah. And they have a lot of ideas. And so it's really about finding the programs that are appropriate for each exhibition.

FW: Um, yeah. I might mention the performance that kicked it all off. Um, we invited Katja Krakowski, who is a performance artist based in New York. Uh, but she was out here at UC Davis as an artist, a teaching artist in residence last year. Uh, we know each other back from Chicago, and, um, she did a performance in the historic ballroom called Bad Woman laughing. And she was inspired by a Betty Saar work. Um, woman with two parrots. That's on view in the Making Moves exhibition. Um, but it was about an hour long performance, um, where there was a combination of the surreal, the grotesque, the uncomfortable, the absurd and comic. Um, and I think one of the goals with that program and where it was really successful is the way that it it brought the museum to life. Um, you know, the museums are living entities. Um, they're not just closets where you shut works away for for decades and centuries. Um, and I think that Katya, the way that she made people feel in their bodies and in their the space, it made you aware of your presence within this, this being that is the museum.

SM: And what I loved about that specific program, which coincided with the opening of the exhibition, is that it created space inside the museum for performance art. Um, historically, there hasn't been a lot of performance art at the Crocker Art Museum. And really, since Francesca was hired, um, we've been able to host. This is the second performance.

FW: Yeah, this is the second. We hosted a performance by Chiffon Thomas in the ballroom about two years ago now. But it's something we want to continue to do more of. I think it pushes you out of your comfort zone in a really productive way. And I think that's what makes contemporary art so compelling and so vital.

SM: And then, um, an upcoming program that we have is we have invited Doctor Rachel Middleman, who is a professor of art history at, uh, California State University, Chico, and she wrote this incredibly important book called Radical Eroticism women, Art and sex in the nineteen sixties. And when Francesca and I were organizing this exhibition, we came together and we both had our copies of Radical Eroticism. And both of these copies were just dog eared and had so many post-it notes in them. And so in so many ways, Doctor Middleman's research has really inspired the erotic part of this exhibition. Um, and so we're just so thrilled to invite her February twenty eighth to the Crocker for a lecture.

HL: Wow. Thank you. It's impressive to hear this idea. I think that so much of the potential for museums is sparking civic discourse after they leave the actual institution itself. And so these ideas filter out into the community. You know, one of the things that in your past research that you mentioned, Francesca, is you talk. You tell a story where you're inspired by Jenny Odell, who is a Bay area writer, and you're specifically referring to a book in which she's focusing on time and how our collapsing of time in the twenty first century kind of affects our beliefs, our behaviors, and so on. And museums, in no small part, are machines for organizing time. What do you think museums need to, quote unquote, unlearn about time right now in our contemporary world, and what should replace what they're unlearning?

FW: It's fascinating that you bring up Jenny Odell, because she's definitely an influence on my curatorial practice and just the way that I think about the world. I love her work. And in that book, Saving Time, she talks about kairos as this kind of synchronistic time. So it breaks out of linear time as we know it, and as so much of history is written. And it's this it's almost like the flow state this time, or this sense of time where there is no beginning, there is no end. It's everything all at once. And I think that is very much our approach to this exhibition, making moves in that there isn't really a starting point or an ending point in the exhibition. And we're not placing any more value or priority over the contemporary works. Um, as we are over the more historic works, or even those artists who are already written into the history book books versus those who are really emerging, and this might be their first museum Exhibition. And I think to have this fluid notion of temporality as well as, um, training of the way that we move through space, um, I think that is an undercurrent throughout so much of our thinking.

SM: Which is very non-hierarchical, I would say also, which is a very important part of kind of the organization of the show. And in thinking about how it's not a chronological show, it's not a show based on geography, um, but instead it's like a different type of movement. Yeah, yeah.

FW: Making moves, making moves.

HL: Indeed. So, you know, this idea of the future of museums in what you are doing beyond the, the exhibition space? Uh, we've got, you know, thousands of years of history with painting and even more so with art forms like ceramics, which Sarah you in no small part have expertise in. Season. And as you mentioned at the start of our conversation, your research around ceramics and how that's informed all of the decisions that you've made in many ways in the museums and your curatorial practice. One of the things I think is particularly interesting is that amidst finding, amidst the changes in the world, is finding relevance of an ancient art form like ceramics or even painting. And how does that pull into the contemporary art world and contemporary art museum exhibition spaces? So what is the role of the museum and ancient art forms like ceramics in a digital society?

SM: I think that is such a very timely, pressing, urgent question. And it's something that I think about all the time. What is the importance of something that's handmade? What is the importance of craft? What is American craft today? In a society in which, um, is becoming more and more mechanized? I mean, with all of these companies, um, you know, creating unlimited amounts of knowledge and resources were made to think that we have more choice, right? We live in a society full of choices. Um, but in fact, I sometimes feel like our choices are becoming more and more limited and kind of prescribed. Um, and so through craft, through ceramics, through the handmade, um, artists are having the opportunity to kind of create something, whether it's a pot or a so say it's a ceramic cup. They are starting from square one with a cup, but they still are in control of the process of making from beginning to end. And it's through that process they're able to make new choices, new decisions, um, ones that are not prescribed. And yeah, I just think, you know, as as our choices become more and more limited, craft has never been more important in the twenty first century.

HL: I want to ask a couple more questions here to see if we can pull things full circle in our conversation. Francesca, taking some of what Sara just said, you've described wanting to broaden the way museums tell stories of of art and experiences that have shaped society's ideas. How does that concept show up in your day to day choices at the Crocker for this exhibition, and the other one that you mentioned that's coming up next summer?

FW: Yeah, that's a great question and I think with the Crocker, you know, we've inherited this incredible history that we've already spoken about at length today. Um, and I think that history is really a beginning place for us to think more expansively. And part of what attracted me to this position is the way that the Crocker is pushing up against the bounds of what we define as California art, which is a very arbitrary designation, if you really think about it in a very contemporary one that is so politically fraught and can mean different things for different people. And when I joined the museum three years ago, I joined colleagues who were really thinking critically about some of these terms and these histories that we've inherited. And so I think it's our role as a museum to continue evolving, um, to continue, um, staying engaged, as I said and as Sarah said. And I think one of the best ways to go about that is by starting in a really focused way. Like it might feel like a niche area. Um, but like a ceramic cup or a vessel, and then zooming out from there and looking at all of the different networks and the communities that are bound up within that. Um, and so kind of using the, the micro in order to approach the macro and some of these larger questions and tendencies of our times.

HL: Wow. I love this idea of approaching the larger tendencies of our time. And even, you know, defining California that becomes something that's, uh, socio politically fraught idea. Uh, to close out here, I'd like to hear both of your thoughts on this overarching theme of what you've really started doing with this incredible exhibition of making moves and where that might move to in the coming years. So when you picture the Museum of the Near future, what do you think will matter more than institutions currently assume, especially in how exhibitions are framed or interpreted and cared for as a part of the public experience?

SM: I think the future of museums and curatorial practice more broadly is that I see a future in which we figure out new and better ways to work with one another and in order to tell new and different stories. So I think the future of museums is much more collaborative, much less about the legacy of a specific institution and kind of the importance of their collection and their their own institutional history, but much more about, um, relationships and fostering and sustaining those relationships and building bridges, um, with other institutions and figuring out how to work with living artists better than we already are. Um, yeah.

FW: Yeah.

FW: And I think within the relationships of the museum, uh, museums are one of the few sites within our contemporary society where the public can come together and gather and experience people and ideas that they might not be familiar with. And so the public piece is also an integral part of that. Um, and the way that our programming is really it, you know, it's there isn't a hierarchy between curatorial and education, but that we are going together and looking for ways to engage the public and learn from the public as well.

Hugh Leeman: Francesca. Sarah, thank you very much. I feel like what you're doing, it really illustrates what you've just answered in this last question here of this collaborative dialogue the two of you have had for this exhibition. But furthermore, you know, before we started, you were talking about how you had crossed paths in your career before coming to the Crocker Museum, and that this is kind of revitalizing that crossing of paths. And it's a beautiful thing that that we all stand to benefit from. So thank you both very much for doing what you're doing.

Francesca Wilmott: Thank you so much for having us.

Sara Morris: Thank you.