Wayne Thiebaud: Art Comes from Art, Legion of Honor

This review is part of our “Artist on Artist” series. The writing is presented in the artist’s own voice.

By: Cedric Wentworth

I went and saw the Wayne Thiebaud exhibition at the Legion of Honor. The man has a sense of humor. He takes himself with a grain of salt. He's one of the only artists I know who knows how to laugh at himself. While making great art.

It's not a big show, but a good one. With some wonderful works by other artists, incidentally, including De Kooning, Balthus, Petersen, Gorky, and Park.

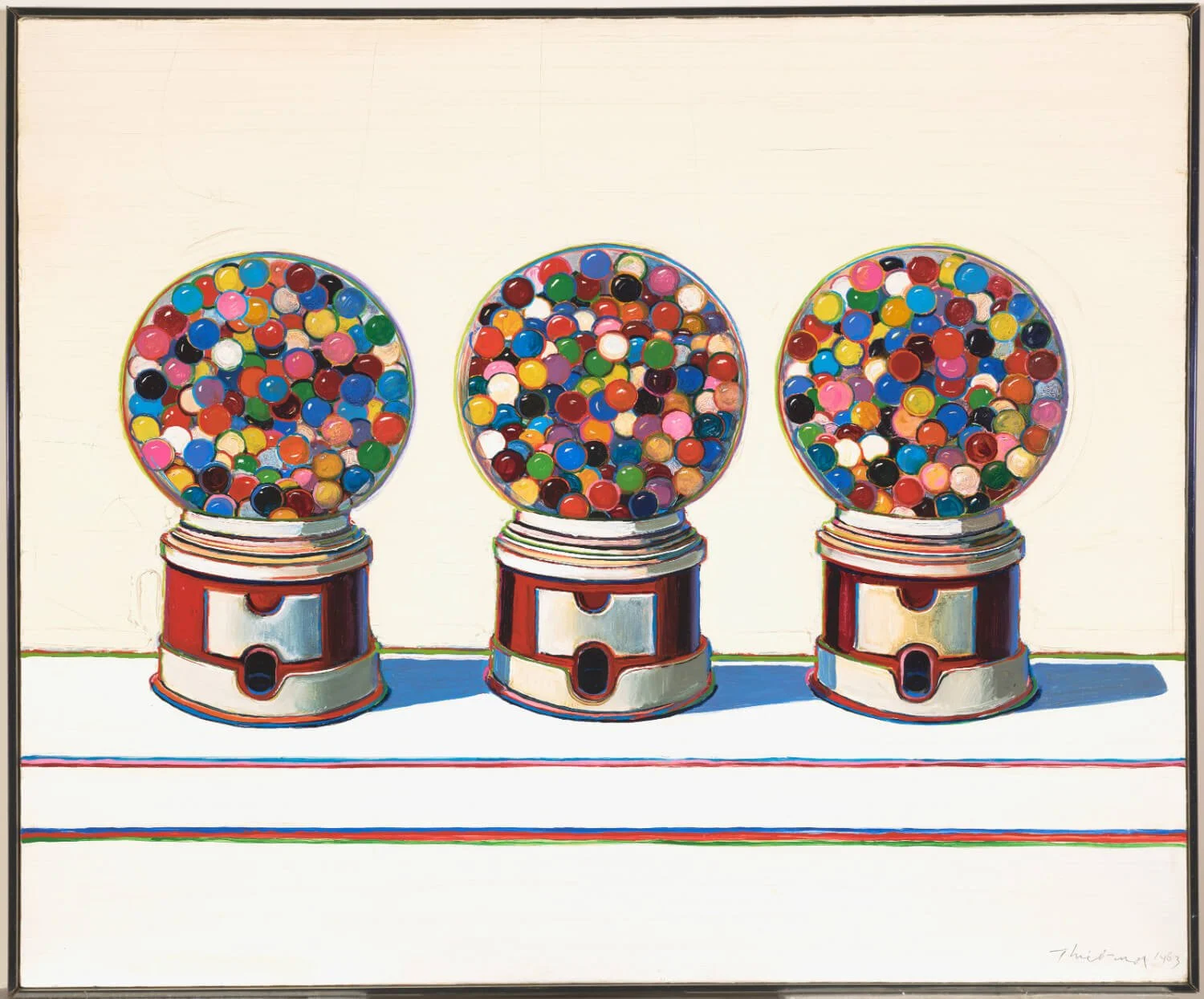

Let's face it: no one goes to the museums. Attendance is down across the board. When I went, with a good friend, we were practically the only ones there, which made for a wonderful afternoon absorbing the selection, followed by a bowl of delicious Korean noodle soup on Clement Street. Thiebaud cut his artistic chops as a commercial sign painter in the forties. As he transitioned into fine art, he brought the wry advertising humor of the roadside billboard with him. Thiebaud understood the power of the image in American popular culture and used that understanding to his great advantage. Take his iconic canvas, Three Machines, owned by the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco and included in the exhibition. Three gumball machines sit on a shelf, clear plastic domes filled with candy. Thiebaud flattens the background, ridding the image of anything extraneous and presenting the candy up close in almost clinical fashion. Doing so allows the viewer to project his own meaning into the work. What do we do with these machines? Look at them as symbols of a 'simpler, happier time'? See them as metaphors for suburban middle-class post-war prosperity? Stand-ins for loneliness and alienation, masquerading as a sugary plenty? The very neutrality of the canvas allows for any number of interpretations.

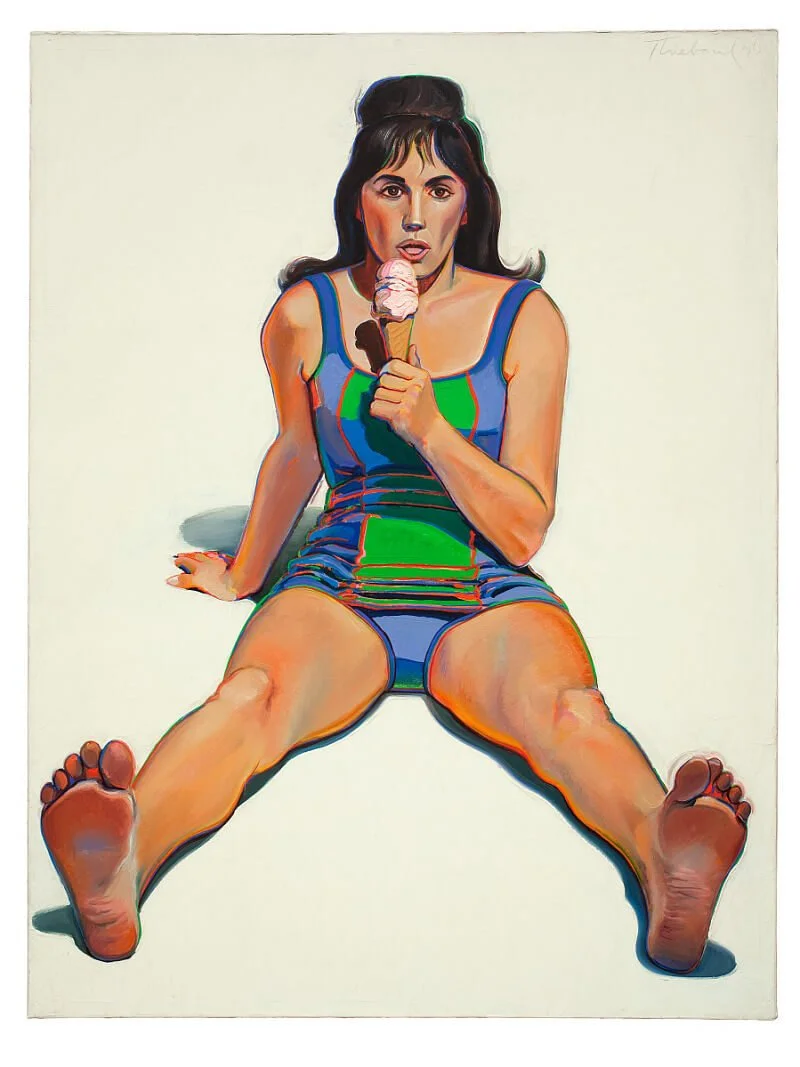

Girl With Ice Cream Cone does the same thing with a human being that Three Machines does with gumballs: takes the subject of the painting and sticks it in an environment devoid of the familiar, like an insect pinned to the interior of a specimen case. An attractive woman in a bathing suit sits on a flat white ground, right arm propping up her torso, left hand clutching a double strawberry cone. Her mouth is open, she's about to take a lick. The pose is frontal, symmetric- almost Egyptian in its symmetry- lending her a sort of stiff formality and to some extent countering the eroticism of her beautiful figure and seductive, languorous expression. She occupies the same chilly psychological space we experienced in Three Machines. We're not sure whether to feel aroused or repulsed.

What's a Thiebaud exhibition without a few slices of cake? They're here, presented on raised cake platters for our visual consumption. Cakes and Pies is a canvas populated by twenty-five delicious confections. Once again pushed to the foreground, and painted in a pastel palette of pinks and greens, rich chocolate browns and pale whites, the sugary food invites us to remember that childhood satisfaction that accompanied a perusal of the glass counter display at the neighborhood bakery. The image is large, measuring six feet by five feet four inches, lending the work a sumptuous grandeur. Again, we aren't sure where to go with it. Is Cakes and Pies merely a decorative 'what you see is what you get' arrangement of form and color? Is it a critique of gluttony? Or is the canvas a wry depiction of the baker's craft?

Cakes and Pies, 1995, Oil on canvas, 72 × 64 in.

Similar to Hockney, one of Wayne Thiebaud's peers, the Sacramento artist objectifies his material, resulting in the divestiture of any emotional or psychological content contained within the subjects of his paintings. What remains is a neutral visual vocabulary that manages to uncannily reflect the bland cultural landscape of a postwar American society stripped of spiritual meaning. Of course, the American Dream is at its core a bold rejection of spirituality. It is all about upward mobility, keeping up with the Joneses, green lawns, and deserted backyards boasting sparkling kidney bean-shaped swimming pools. In such an environment, the human being, like a beautiful trophy wife hanging off the arm of a smirking politician, is as interchangeable as a piece of lawn furniture, simply another thing we wish to consume. Suffering, the pain of loss, the joy of connection, and the unique individual emotional experience that makes humans human and defies analysis except through the artist's genius, have been stripped away, as indeed these experiences remain extraneous to consumer culture and should be recognized as an impediment to capitalism. Seen through such a lens, Thiebaud's canvases may be interpreted as powerful metaphors of the New World society from which they have been birthed.