Harry Bowden, Works from the Estate, Incline Gallery

By: Kelly Jean Egan

This exhibition at Incline Gallery in San Francisco brings together over ninety works by modernist painter Harry Bowden, many of which are being shown publicly for the first time. Sourced from the estate of Charles Campbell and Glenna Putt—Campbell having unexpectedly inherited Bowden’s entire body of work after Bowden’s wife, Lois, passed away in 2001—this collection offers a rare chance to see the full breadth of his practice in one place. The available works entice both devoted Bowden collectors and those simply drawn to good painting.

Harry Bowden (1907–1965) was multifaceted, he formed a part of several important artist subcultures in the mid-twentieth century. Born in Los Angeles and later drawn to the energy of 1930s New York, Bowden moved in the kind of circles that shaped American modernism from the inside out. He studied under Hans Hofmann, a well-known abstract colorist, and painted alongside artists like Willem de Kooning and Fernand Léger on WPA murals. A friend and collaborator of Edward Weston, Bowden photographed contemporaries like Lee Krasner and Jackson Pollack, and helped launch the American Abstract Artists group—all while quietly forging a style that was his own. He belonged to an era when art was shifting, unsteady, full of risk—and Bowden, in his steady, thoughtful way, was right there in the thick of it.

Bowden started out like many young artists of his time—studying at the Los Angeles Art Institute and continued in NYC at the Art Students League, later picking up commercial design work in LA to get by. But everything changed in the summer of 1931, when he took a class with Hans Hofmann at UC Berkeley. Something clicked. He wasn’t just learning technique; he was seeing the world differently—through rhythm, structure, color. That summer made his path clear. He left behind the safety of commercial design, moved to New York, and threw himself into painting. Studying with Hofmann again, eventually becoming his assistant on E 57th Street in 1935, Bowden found himself surrounded by artists who were breaking the rules and making something entirely new. It wasn’t about chasing fame—it was about chasing the work.

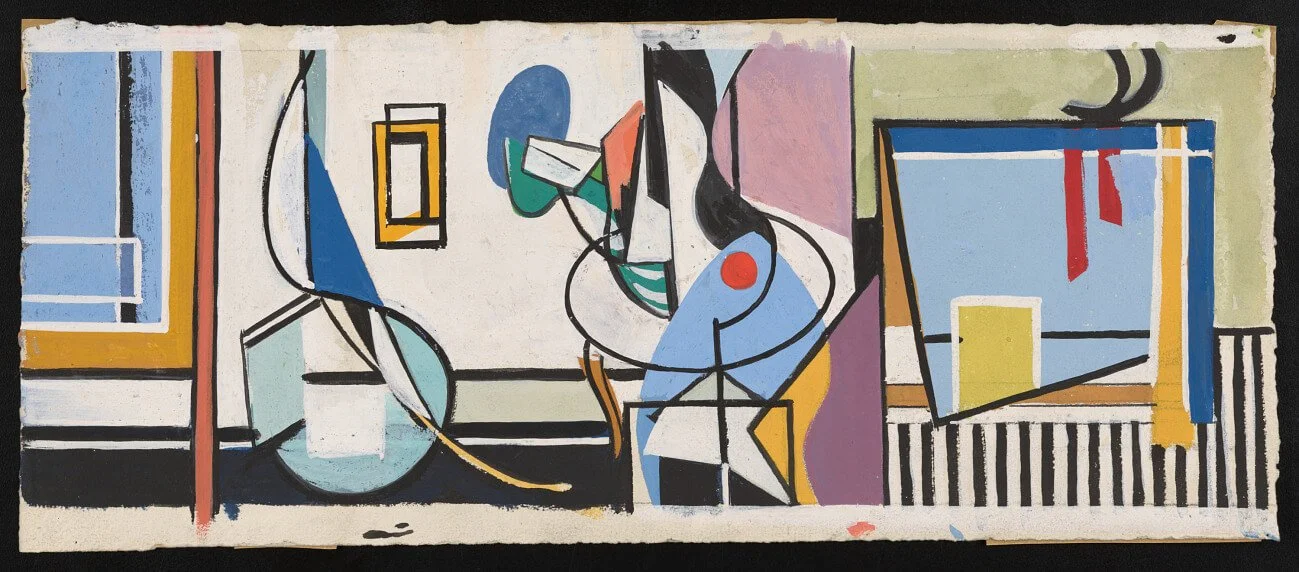

In those early New York years, Bowden’s work leaned into abstraction—bold, architectural compositions that echoed the influence of Hofmann but carried a quieter, more lyrical tone. He joined the Federal Art Project sponsored by the Works Progress Administration (WPA), and collaborated on mural designs alongside artists like de Kooning and George McNeil. It was a formative time, both in the studio and out—nights spent in conversation, canvases traded between friends, ideas passed back and forth like currency. Bowden helped found the American Abstract Artists group in 1936, aligning himself with painters who believed in the radical potential of non-objective art. His paintings from this period balance clarity with experimentation—shapes hovering between the constructed and the intuitive, color fields that hum rather than shout.

Take Untitled, 1938, for example—a gouache that shows Bowden at his most subtle and searching. His hand feels both assured and exploratory, with soft washes of translucent blue forming a backdrop that immediately evokes sky, or at least the sensation of open air. That airy ground shifts the viewer’s perception: what might otherwise read as pure abstraction begins to suggest space, even atmosphere. Against this gentle expanse, Bowden overlays a loose scaffold of ochres and rust-toned lines—angular yet tentative, like the memory of a structure rather than the thing itself. This creates a nostalgic melancholy as though the viewer is looking at a photo of old friends. The painting holds its form loosely, inviting you to consider not just what you see, but what might be vanishing or forming within it. There’s no urgency to resolve it. Instead, Bowden lets the gouache breathe, as if he's more interested in evocation than in answers.

Bowden’s turn toward figuration in the late 1930s to early 1940s brought with it a remarkable body of works on paper in pastel, many of which will be on view in this exhibition. Pastel suited him—it offered immediacy, richness of color, and a directness of touch that mirrored the intimacy of his evolving subject matter. In these pieces, figures and forms emerge through luminous strokes and soft edges, balancing structure with a sense of fleeting presence. Some may view them as mere studies, yet they exude the sophistication of fully realised works that capture Bowden’s hand and mind in unguarded conversation. For viewers, their rarity and freshness lie not just in their beauty, but in the way they distill the artist’s vision—bridging his abstract foundations with a more human, tangible world.

Building on that intimacy, Untitled, Pastel on paper offers a vivid example of how Bowden harnessed the pastel medium to its fullest potential. Here, velvety sweeps of color—warm terracottas, muted greens, brilliant blues and pale ochres—gather and dissolve across the surface, their edges blurring as if caught mid-thought. The renderings suggest the human figure, but only just; they drift between recognition and abstraction, inviting the viewer to linger in that space between one’s form and one’s aura. Bowden’s touch is confident yet tender, each mark carrying both intention and openness. There’s a sense of immediacy here, as though the work was created in a single sitting, but also a quiet precision that speaks to years of disciplined observation. It’s a piece that hums in the present moment, holding you there with its balance of warmth, mystery, and restraint.

Moving into the 1950s, Bowden’s main work took on a new density and deliberation. While continuing to work with the immediacy of pastel and watercolor, adding the layered richness of oil paint, he began producing more detailed compositions that balanced abstraction with recognizable subjects. In these years, landscapes and figures emerged with greater clarity, yet still carried the structural experimentation and spatial ambiguity that had always defined his vision. The result was a body of work that felt both grounded and elusive—paintings that could suggest place or presence without ever surrendering fully to depiction. It was a period of refinement, where Bowden’s command of form, color, and texture reached a quiet maturity.

(Above) Untitled, Pastel on paper

The Bay, Oil on canvas, 1957, depicts an abstract Sausalito shoreline, the home of Bowden and his wife, Lois, for many years. The painting, from Bowden’s mid-century period, demonstrates how oil allowed him to layer his ideas into something both lush and deliberate. Earthy greens and rusty horizons anchor the composition, while fractured planes of deeper blue and sienna break across the surface like shifting light. At first glance, the forms might read as landscape—a skyline suggested here, a cluster of shapes implying trees or structures there—but Bowden resists full disclosure. Instead, he builds a rhythm of color and geometry that keeps the scene suspended between place and abstraction, giving the viewer the liberty to co-define the scene. The brushwork is patient yet alive, each mark seeming to answer the one before it, creating a conversation between solidity and movement.

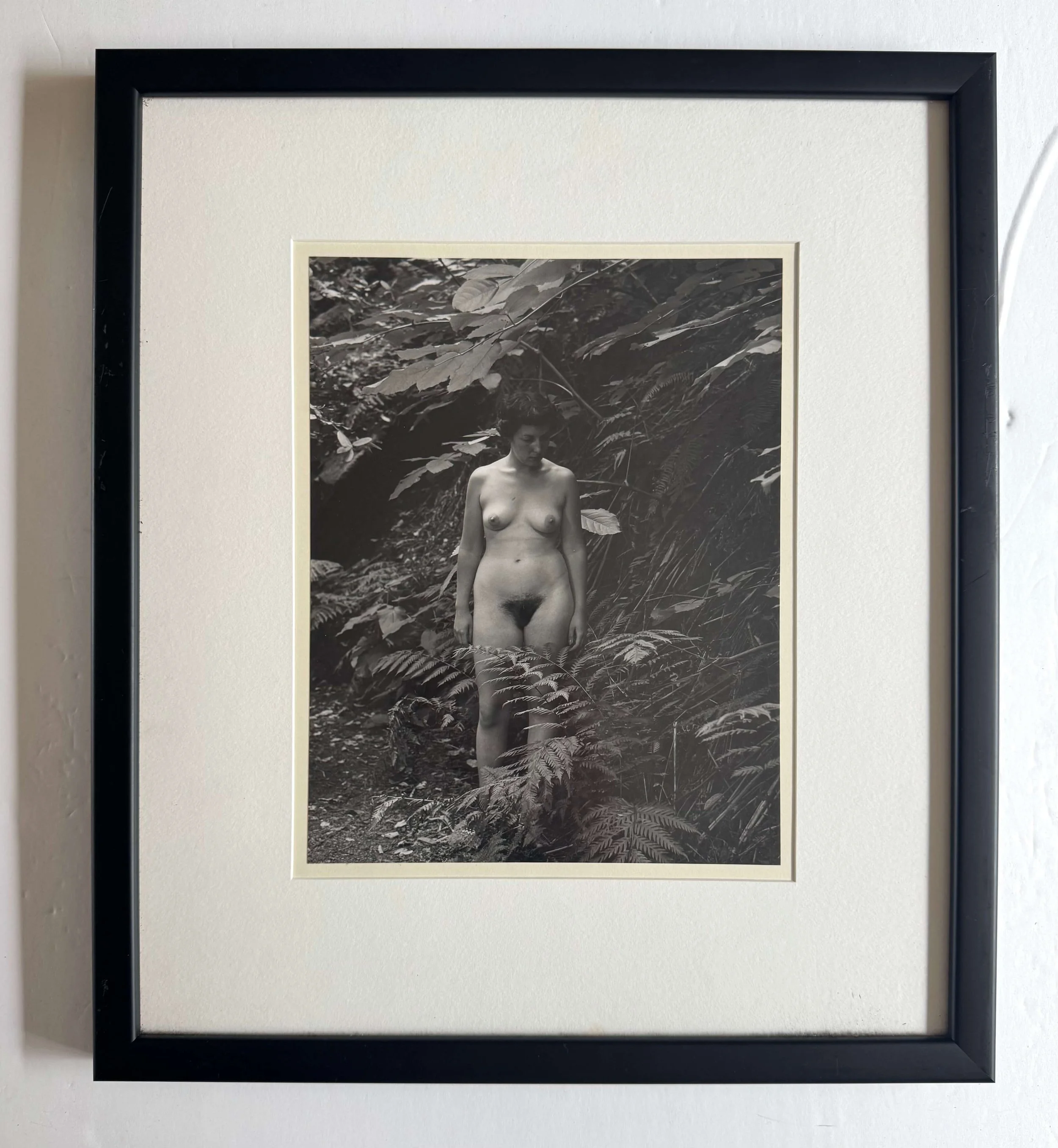

Standing Nude, oil on canvas, 1952 turns that same formal language toward the human figure, though in Bowden’s hands the body is refracted through a prism of abstraction, drawing from his earlier pastel works on paper. The scene depicts a nude female figure, foregrounded on the right with an abstracted background. The central form is anchored by strong verticals and deep, warm tones, yet its edges dissolve into surrounding color fields, as if the figure were emerging—or receding—into its environment. Bowden uses the viscosity of oil to create subtle transitions, letting some passages bleed and others remain crisp, heightening the sense of ambiguity. It is difficult not to acknowledge the parallels with early 20th century German Expressionism. It’s a portrait without specificity, a study of presence rather than likeness, and it reveals how, even when drawing from the figure, Bowden remained committed to exploring the space where recognition gives way to feeling.

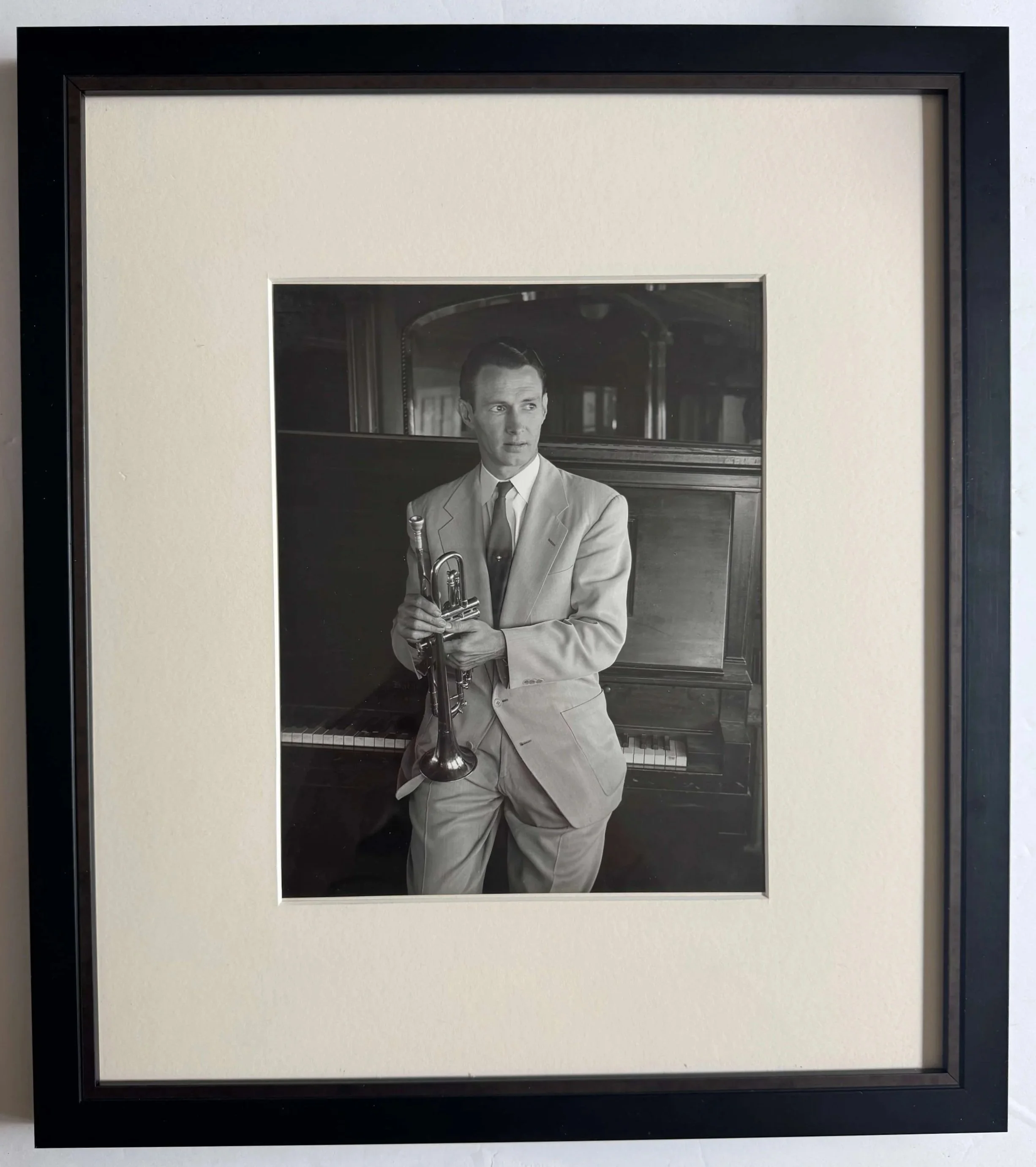

One of the most interesting and underappreciated facts about Harry Bowden is that he was not only a painter but also a remarkable photographer who quietly documented the emergence of various art scenes—capturing candid portraits of Ad Reinhardt, Gordon Onslow-Ford, Luchita Hurtado, Hassel Smith and Imogene Cunningham amongst many others, often in their studios or at work. Bowden did not exclusively photograph fellow painters and photographers, the portrait below titled Bob Scobey on Ferry Boat Fort Sutter, 1953, is a fine example of this. Bowden reportedly took to the traditional jazz revival movement in 1940s San Francisco, making a number of portraits and photographs capturing this movement. Bowden has been described as a reserved and quiet man, however when it came to art and jazz, he spoke with fervorous enthusiasm and passion. Charles Campbell, from whose estate these works have been sourced, had a similar love for jazz, often attending performances with Bowden and posing for photographs alongside notable musicians. This forged a solid friendship between the two, built on their mutual love for all things art and jazz.

Unlike many of his contemporaries who either painted or photographed, Bowden did both with equal seriousness. His photographs were not just snapshots—they were composed with a painter’s eye, revealing the mood, tension, and intimacy of the emerging postwar New York art scene. He moved fluidly between media, and his images are now considered essential visual records of mid-twentieth century American art and music history. What makes this especially compelling is that Bowden wasn’t a documentarian from the outside—he was inside the movement, painting alongside these figures and shaping the discourse through both his brush and lens. It’s a dual legacy rarely seen and even more rarely credited. It's noteworthy that Bowden’s photographs are in the permanent collections of the Museum of Modern Art, New York, and the University of Los Angeles Library Special Collections.

While many attribute certain styles of Bowden’s to particular time periods, in reality we know he practiced multiple disciplines simultaneously, weaving his quintessential characteristics into every artwork he created. One could even argue that Bowden fits into the Bay Area Figurative Movement which emerged during the time period he was in Northern California (in 1948 he taught color, anatomy, and figure drawing at the California School of Fine Arts), although his self-identification was as a New York abstract artist. The collection on view is not only robust, it truly offers attendees a comprehensive view of a lifetime of work, assembled and displayed together for the first time. The show, at Incline Gallery in the Mission District of San Francisco, opens tomorrow Friday, August 15 and will run for two successive weekends, closing on August 24, 2025.