The Bridge Studio Collective, 111 Minna Gallery

By: Doug Welch

The Bridge Studio Collective, comprising Adam Feibelman, Daniel Chen, Alice Koswara, Jon Stich, Robert Bowen, Daryll Peirce, David Choong Lee, Eric "HiERICBRO" Broers, Jillian Knox, Jennifer Banzaca, Leon Loucheur, Lisa Kairos, and Chad Hasegawa—brings together painters, illustrators, photographers, paper sculptors, textile artists, and designers who share studio space at 333 Bryant Street in San Francisco's South of Market neighborhood. Formed in 2023 when the building was converted into artist studios, the collective now presents its work at 111 Minna Street Gallery in an exhibition curated by Robert Bowen. The gallery space truly lends itself to such a diverse display of art. With its two massive exhibition rooms, the high ceilings, vast wall space, and well-designed lighting, each artwork receives its due, creating a fluidity as one traverses through the show. Though the artists' practices vary widely, they are united less by style than by a shared attention to detail, an unwavering dedication, and a deep immersion in their respective processes. The show includes a site-specific mural by Hasegawa, wholly created and installed at 111 Minna.

Adam Feibelman, a Bay Area artist for nearly 30 years and a graduate of California College of the Arts in illustration and printmaking, is best known for transforming stencils into artworks in their own right, not merely as guides for paint, but as forms themselves. For this exhibition, he presents three mixed-media pieces, including Home is Where the Heart Was, a composition of cut paper, drawing, collage, and intricate stenciling. Essentially, all of Feibelman's work included here consists of dozens of separate works within the confines of a larger composition. Each work is an amalgamation of figures, abstractions, geometric forms, and representations of nature, several narratives coexisting at once. In one vignette, a bird hovers above what appears to be a snake beside a series of paper-cut stars; in another, two people hold hands beneath a flower. Notably, the same snake reappears elsewhere, now superimposed on the figures, transformed from snake into something more ambiguous perhaps a visual metaphor for the flow of emotion in human union. Interestingly, the same motif triggers different sensibilities and activates separate narrative and emotive qualities.

Feibelman's piece allows for an almost infinite number of interpretations, depending on whether the viewer focuses on the whole or a single vignette. Gridlike cut-paper patterns, peace signs, and faces create a sense of familiarity amid apparent disorder. The work recalls the noisy landscape of the mind, thoughts, memories, and themes colliding. As a natural narrative develops, the best path is often to simply observe. By populating countless possibilities into one frame, Feibelman relinquishes control of meaning as his title suggests intention yet remains open-ended, inviting viewer participation. The fragile paper elements, framed under non-reflective glass, resonate without contrivance. This complex work does not disappoint.

When it comes to Daniel Chen's paintings, the human eye is tested. The artist uses oil on canvas to create linear, pixelated art pieces. Chen, a San Francisco based artist with degrees from the Academy of Art University and the California College of the Arts, presents six oil paintings in this exhibition. In "A Love

Story" the lines are clean and precise, making one question whether the entire composition is machine generated, (it isn't). Hand-painted diamond pixels create an urban scene; a street intersection. To the naked eye, shifting colors delineated by the diamond pixel are most prevalent. The image depicted is highly abstracted through painted pixelation; its true form is perceptible but barely so.

Interestingly, when the painting is photographed with an iPhone camera, the underlying shapes and forms of a city become abundantly clear; the phone's automatic processing features, which can adjust color and contrast, distorted what the human eye saw. Although in this case, it penetrated the intended op art quality and offered an image that eliminated Chen's visual distortion. Shifting colors suddenly become a person, cars, lights, the façade of a building, and other essential parts of a city neighborhood; it was as if the painting came into focus. Rather than spoil the painting, the camera revelation heightened understanding and appreciation of what Chen conveyed with pigment. The street scene, which comes alive with this augmentation, is viewed in its painted form as though one were looking at it from a distance. The intentional distortion invites the viewer to connect without the weight of pre-scripted narratives about San Francisco. An attention to detail is required to establish a scene and formulate a full narrative. The abstraction forces patience and attentiveness, mirroring the conflict between promised usability and the reality that technology is initially confusing to navigate.

Alice Koswara, a San Francisco–based artist who earned her BFA in Graphic Design from the Academy of Art University in 2009, brings her background in design, detailed illustration, and bold color to the acrylic painting Lady and a Red Fox. The work combines a portrait of a woman with that of a fox. The colors are bright yet soft: a pale blue background contrasts with dark voluminous hair, while the face is animated by hues of red and orange. Similar tones carry into the woman's coat, on which a red and white fox looks upward toward the sky. A warm orange ground and yellow sun complete the scene, leaving the impression of a day's end, with the sun in slow descent.

Placing the fox on the woman's coat conveys a union of human and animal; the fox is not a possession but an equal. The mirrored colors of fox and desert with those of the woman's face suggest interconnectedness, or perhaps shared qualities—intelligence, cleverness, adaptability. The heat of the background evokes survival, resilience, and perseverance. What might initially appear as a simple portrait reveals layers of symbolism and mystery, encouraging a personal connection with the viewer. Koswara exhibits 19 additional artworks, all of which are female figures, usually from the waist up. The works vary from acrylic to watercolor with each piece solidified by the bold, contrasting block-style colors and soft yet cemented lines. The pieces are inviting and friendly, as though they are photos of old friends or illustrations from your favorite childhood novel.

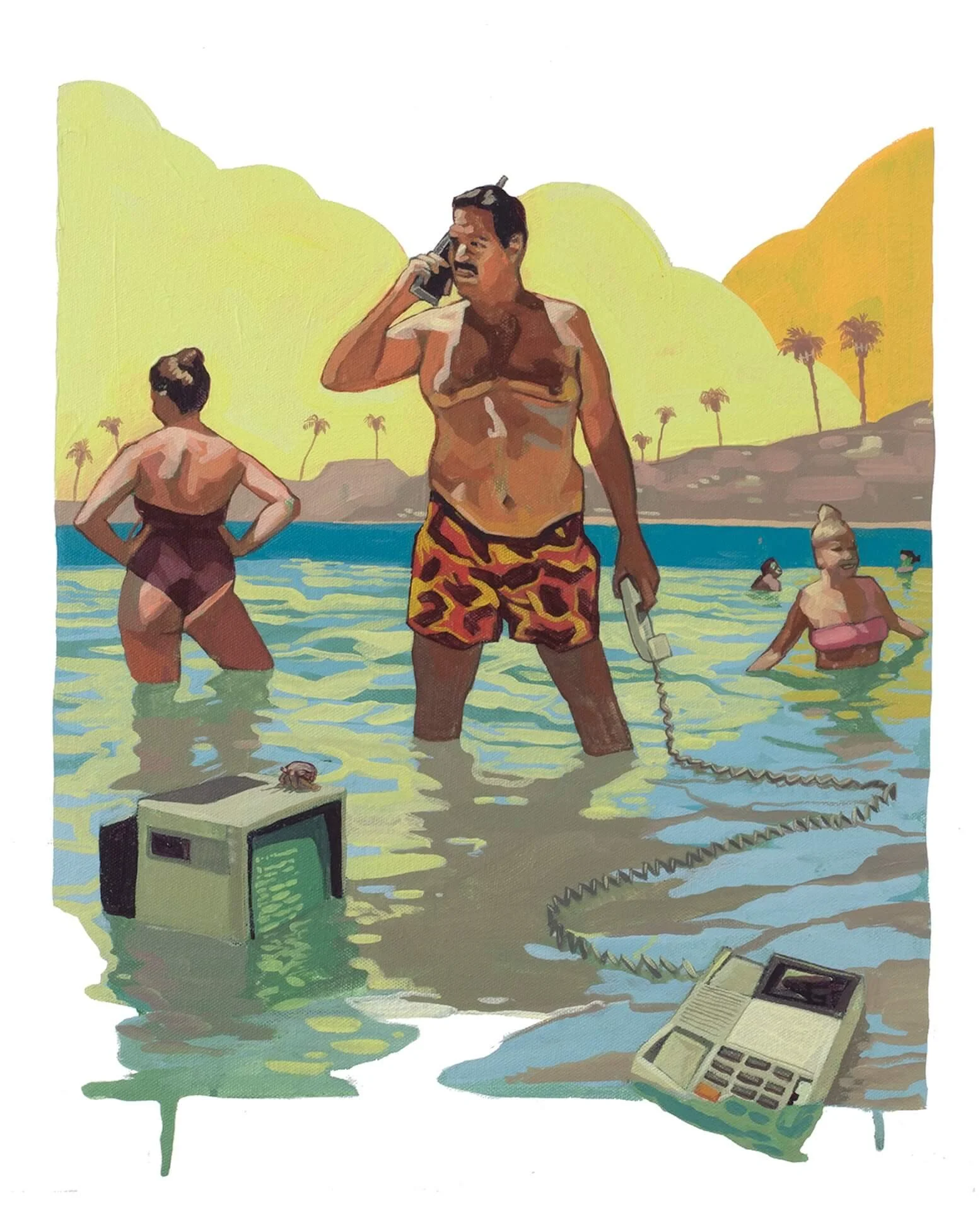

Jon Stich, a San Francisco–based artist who graduated from California College of the Arts in 2004 and whose illustrations have appeared in numerous publications and brands, brings his sharp eye for narrative and absurdity to the acrylic and colored pencil painting Business Center. The work presents people in water—perhaps a communal swimming pool or hotel pool—while a man holds the receiver of an analog phone with its base partially submerged, at the same time pressing a first-generation cellular phone to his ear. Nearby, an older model computer with green-on-black text glows faintly, a crab perched atop it. All of this unfolds against a desert landscape. The man's seriousness contrasts with the absurdity of his surroundings: obsolete technology sinking into water. Do we have a misplaced sense of importance here? Or is this a comment on our search for meaning, security, and continuity amid chaos?

Business Center layers incongruous elements to unsettling effect: neither phone nor computer belongs in water. Stich compels us to reflect on how devices have infiltrated spaces once associated with relaxation. The dual phones suggest both technological progress and our tethering to it. Even as devices become freed from cords, are we ourselves less free? Do we ever really break from our work responsibilities? The corroding electronics remind us that today's most advanced tools, too, will eventually be obsolete. The piece reads as a single absurd moment yet also as a meditation on transition and impermanence. As viewers, we are invited to question technology's omnipresence and our complicity in it. The work resists easy answers, leaving us with questions that feel increasingly urgent.

(Above Left) Jillian Knox, La Mesa de mi Suegra, Digital Print on Crystal Lustre Archive Paper | 24″ x 36″ | 2020 | Profits benefit CHIRLA

(Above Right) Jennifer Banzaca, Blue Oasis, Acrylic on Canvas | 17.25″ x 13.25″ | 2024

(Below Right) Flail, Robert Bowen, Acrylic on Canvas | 86″ x 62″ | 2025 (above)

While this review has highlighted only a handful of works, the exhibition is enriched by contributions from Robert Bowen, Daryll Peirce, David Choong Lee, Eric "HiERICBRO" Broers, Jillian Knox, Jennifer Banzaca, Leon Loucheur, and Lisa Kairos, artists whose practices stretch across illustration, abstraction, photography, textiles, and sculpture. Together, their works expand the range of voices within the Bridge Studio Collective, underscoring the strength of a group that thrives on difference as much as connection. On view at 111 Minna Gallery through mid-September, the show rewards slow looking and repeat visits. The gallery itself equal parts bar, café, and cultural hub remains one of San Francisco's most inviting spaces to encounter contemporary art, where the experience of the work is inseparable from the atmosphere of community it fosters.