Pamela Carroll, The Beauty Inherent, Bakersfield Museum of Art

By: Hugh Leeman

Pamela Carroll's exhibition, The Beauty Inherent, at the Bakersfield Museum of Art presents 45 hyperrealistic still-life paintings depicting brightly lit produce, plants, and seashells, staged in elegant minimalism with complementary tonal shift backgrounds. Beneath her thin-layered glazes, history's symbolism hints at a contemporary commentary connected to the 17th-century Dutch and Spanish masters who inspire her art.

Although the paintings transmit the academic acumen of an atelier education, Carroll is a self-taught artist. She began making art as a child, and in adulthood, she was taken by photorealism, painting fruits and vegetables in the 1970s before taking a 16-year break from her art practice to raise a family. The long-running thread through her career of still life realism stretches towards the 1950s as she notes, "From a young age I really liked copying things and making them look real." [1]

Still-life painting remains synonymous with the 17th-century Netherlands for its hyperrealism and coded cultural commentary amidst phenomenal social change. Yet, Carroll's works are far more compositionally influenced by the contemporaneously created bodegónes. The term "bodegón" comes from the Spanish word "bodega," which refers to a storage room often used for storing food goods.[2] Unlike the more lavish 17th-century Dutch still life, which featured dynamically stacked objects to add depth, bodegones were typically minimalist in their composition, with objects isolated in shallower space, often depicting uncooked food stored in such a room.

Bodegones, like Dutch still life, often appear as a celebration of objects, the former frequently more aesthetically austere than the latter, which testify to the rapidly expanding 17th-century Dutch economy, globalization, and their brief domination of the colonial sphere. Both, though, possess the potential to tell stories through their often inanimate objects that expand our understanding of social issues and, to varying extents, warn of excess.[3] In Carroll's work, at times a vegetable is just a vegetable, undeniably celebrating the beauty in daily life; yet, in others, a complex syntax of symbolism speaks to societal changes similar to those experienced by her 17th-century predecessors. The origins of which date back to her early fascination with still life, as the artist says, "When I started painting still life, I thought it would be fun to weave a story around the objects."[1]

For Carroll, like her precursors in the 17th century, fruit on a table may well be simply fruit, though through her careful curation of objects, an encoded allegory emerges. Such a story of societal change, woven around objects, is best illustrated through Succulents with Basket. The succulent, well-known for its ability to survive in water-scarce areas, acts as a symbol of adaptive resilience. The basket, long used as a symbol of harvest, contains multiple succulents that rest atop a raw wooden table, beside a wrinkled linen cloth hanging off the edge of the table, its squared fold pattern indicating attempts at imposing order. Light from above heightens the soft organic tone of the table and the basket's wood.

In 17th-century Netherlandish still life, objects like lemon peels and tablecloths frequently hung precariously off the edge of tables, underscoring the inherent uncertainty of the future while alluding to the dangers of excess. In Carroll's Succulents with Basket, the hint at modernity is in the mass-produced plastic pot, suggesting the succulent it holds is to be transplanted, yet for now it sits so close to the edge, its freshly watered soil has released a small puddle dripping over the edge.

The painting's objects and precarious placement paint a portrait of the artist's native California, specifically where she lives in Carmel. Carroll has said of her paintings' realism, "I want the viewer to feel like they have a connection to my work."[4] Such a connection is deeply felt in her hometown, where water scarcity poses such a significant challenge that it has led to building moratoriums.[5] While the artwork was painted in 2021, four years before the museum exhibition in Bakersfield, the visual metaphor of water scarcity easily extends to the historically rich agricultural area that makes significant contributions to America's domestic food production. It has and is currently experiencing such water insecurity that fields have gone fallow, and barren land is being covered with solar power.[6] Through the warp and weft, the basket of historical abundance weaves a modern warning that the artist made four years before, around an ancient idea: what we reap is ultimately sown.

While Pamela Carroll's storytelling through subtle symbolism is present in several works, her technical prowess is never absent. Making her paintings all the more impressive in a technologically dependent modern world is her process. Reached by telephone at his home in Monterrey, Post-modern artist David Ligare, who exhibits with Carroll at Winfield Gallery in Carmel, noted of Carroll's art, "Pamela is a wonderful artist, in a very interesting way. First of all, those still lifes are all done by eye, using no camera. She is able to look at a piece of fruit or shell and then analyze it and recreate it on the surface of the painting. It is an important metaphor to analyze something, act on it, and recreate it." This process, like the symbolism within her still-life realism, distances her from contemporary still-life painters' use of photos for reference and further connects her to the 17th-century masters who laid the foundation that she builds upon. Ligare adds, "She is a camera, she has an incredible eye to see what is on the surface, seeing what is there, seeing the light and what is coming from the surrounding area."

In Lemons in Spongeware Bowl, the artist further connects symbolism from past centuries' still-life masters to contemporary challenges through subtle tones of allegorical prose and phenomenal realism. An idealized prime of the life cycle is transmitted via pink citrus flower buds and lemons at all phases of growth from unripe lime green to plump lemon yellow. An abundance of fruit overflows the Spongeware bowl, and some have rolled across the table. Such bowls gained popularity in 19th-century Scotland and were subsequently exported to America via England. Notably, they often emulate luxury-priced blue and white Chinese porcelain and its later Dutch Delftware counterpart.[7]

However, Spongeware is the most modest of imitators as it is neither porcelain nor glazed in cobalt blue; it is simple, earthenware clay painted with blue splotches using a sea sponge. It served as a utilitarian object in the common person's kitchen, underscoring the beauty the artist indicates is inherent in everyday life. Its presence here conveys humble restraint, contrasting the desires of overflowing excess. The gorgeous citrus's surplus seemingly whispers of an external beauty contrasted by the sour insides of excess.

In allegory's absence, there is a spiritual presence transmitted through Carroll's hours of looking, observing, and rendering an object. Such a presence shines off the skins in Heirloom Tomatoes; the greatest element of the image is its imperfection. The fruit's asymmetrical form, unmodified by modern agriculture's mass production, and marbled flesh with the green curling calyx recount what is often lost in an era of Photoshop and filters. In the absence of a camera in Carroll's process, we can reconnect with the painter's profound role throughout centuries of art history when documenting was more than the push of a button.

Beyond produce, Carroll's talent as a realist painter shines in glistening light reflecting off the edge of seashells. A collection of conch shells and bivalves decorates a linen-covered table in Sea Shells. The wrinkled linen beneath the collection of shells bears square fold lines suggesting humans' desire to impart order and structure amidst the wrinkled chaos of daily life. The shells' beautiful luster makes it all too easy to forget they were once a living thing's home, reminding us of loss.

While Spanish and Dutch Still Life painters depicted such shells to address a broad spectrum of their contemporary concerns, a common theme was the fleeting nature of worldly possessions, as seen here one can't help but return to Carrolls native California and her town's Carmel Bay, where significant ocean acidification, makes it difficult for sea creatures to produce shells effecting their ocean ecosystem.[8] Carroll's careful rendering of the shell collection as one pokes past the table's edge, coupled with current circumstances, imbues the beauty of the shells with a powerful, foreboding tone in our era of excess.

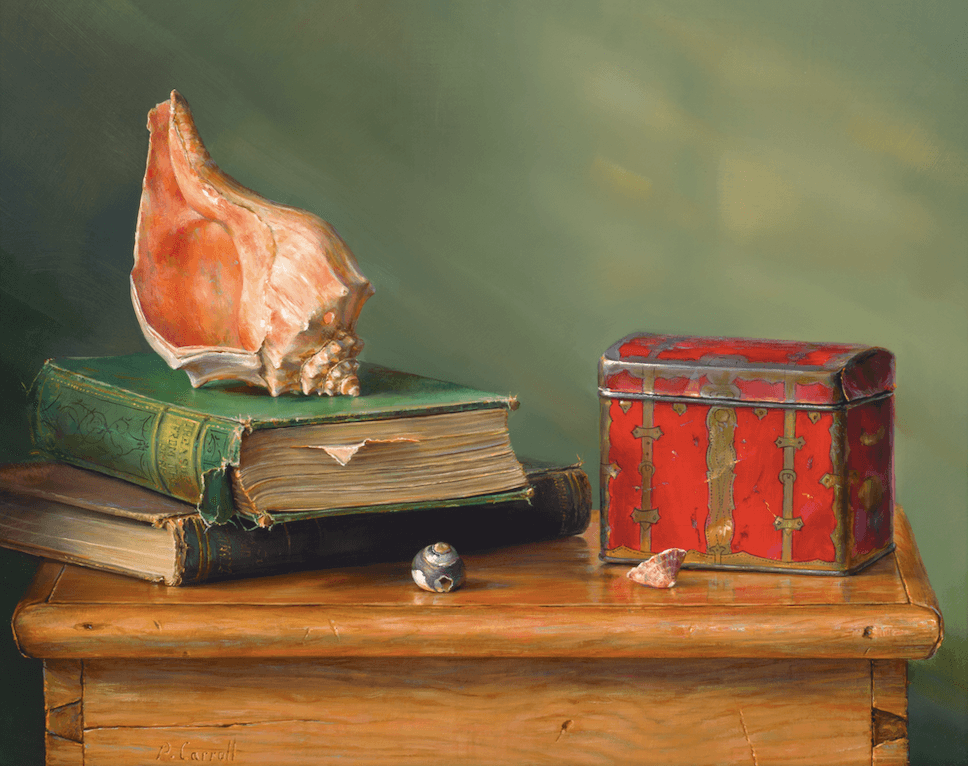

Still Life with Shell, Books, and Tea Chest collects elements of symbolism through the objects, setting them on a worn-down bedside table, whose seams widen like those of the dented tea chest; one can imagine the table wobbling under the weight of the objects. Its well-worn state forms a visual connection with the aging edges of the fraying book covers' yellowed pages. One book's title, Treasures From the Deep, infers a deep-sea of memories, a protruding bookmark denoting the passage of progress toward the end of a story, reminding us that objects like life itself give way to time. The seashells take the well-worn metaphor one step further as two of the three bear the mark of predatory holes, their body gone, the third shell cracked in half, each telling us, amidst the shiny veneer, what once was is no more.

David Ligare went on to share with me that "Though she [Pamela Carroll] is not looking at Cézanne, she is making something that is made of Cézanne's thinking, where he said he would like to paint the world in an apple, what he meant is that he paints the apple and the atmosphere that the object is in and this is what Pam does, with the reflections, the wonderful points of light and the lightened areas around these points that make them so round and so real." Clearly, at times, an apple is just an apple; yet, at others, the whole world can be found in the light that reflects off the fruit's skin, allowing us to see the world in novel ways as it is reflected back at us through art.

Amidst Carroll's pursuit that started in childhood to copy things and "make them look real," she describes her love for still life as a place where one can find what she calls "part illusion, part reality."[9] She has clearly created an incredible visual illusion, but the reality they express is more complex. Amidst the grammar of art history, Pamela Carroll's The Beauty Inherent constructs sentences that speak of the present through a language of the past bearing echoes of history's tendency to, if not repeat, then rhyme. Patiently, in immaculate depictions, they display the beauty of a simple berry and the profundity of observing. Via a ciphered syntax, Carroll's more complex compositions remind us, with optimism, that if we heed the warnings found in the still life of 17th-century empires, cautioning against excess, our resilience, like that of the succulent, can carry us through.

Citations:

1.Art, Southwest. "Portfolio | Keeping It Real." Southwest Art Magazine, 20 Oct. 2015, www.southwestart.com/articles-interviews/feature-articles/portfolio-keeping-it-real.

2.Bodega, N. Meanings, Etymology and More | Oxford English Dictionary. www.oed.com/dictionary/bodega_n?tl=true.

3.“Bodegones.” Obo, www.oxfordbibliographies.com/display/document/obo-9780199920105/obo-9780199920105-0094.xml.

4.Carmel Art Association. “Solo Show, ‘FRESH PRODUCE’ Featuring Pamela Carroll | Carmel Art Association.” YouTube, 18 Nov. 2020, www.youtube.com/watch?v=bZpvjgJCl20.

5.“Fact Sheet | Mpwsp.” Mpwsp, www.watersupplyproject.org/fact-sheet.

6.Vollmer, Madi. “KERO 23 ABC News Bakersfield.” KERO 23 ABC News Bakersfield, 20 May 2025, www.turnto23.com/news/in-your-neighborhood/bakersfield/as-water-dries-up-solar-moves-in-across-the-central-valley.

7. Diagnostic Artifacts in Maryland. apps.jefpat.maryland.gov/diagnostic/Post-Colonial%20Ceramics/SpongedWares/index-spongedwares.htm.

8.“Monterey’s Not-So-Hidden Secret for Addressing Ocean Acidification: Marine Protected Areas.” Center for Ocean Solutions, 28 Oct. 2015, oceansolutions.stanford.edu/news/montereys-not-so-hidden-secret-addressing-ocean-acidification-marine-protected-areas.

9.Principle Gallery. “Pamela Carroll - Principle Gallery.” Principle Gallery, 17 July 2025, www.principlegallery.com/alexandria-artist/pamela-carroll.