Roderick Kiracofe

The following are excerpts from Roderick Kiracofe's interview.

Interview with Roderick Kiracofe

From Small-Town Indiana to Quilt Historian

Hugh Leeman: Roderick, Tell me the story of how a guy who grew up in small-town, rural Indiana in the nineteen fifties with no artwork in his childhood home goes on to become a historian of quilting, with a quilt collection so impressive that it's been lent and donated to multiple museums.

Roderick Kiracofe: Kind of all unexpected, as most of my life. I certainly didn't set out to do that by any means. In the house I grew up in, my parents bought it from my grandparents and my great-grandmother. The three of them built the house. My mother grew up in it. Then she and my father bought it from my grandparents. So there's just this tradition and history which they made. We were all very aware of it. I think I just came in with this love of history, old things. I loved going into our garage or our basement and seeing just old stuff down there, over around the corner. My grandmother lived, she had a basement and just going down there and just kind of seeing what seemed like cool stuff to me. I think that ingrained just this sense and wonder about history, the past, what came before.

In junior high school we're studying Indiana history, and some friends and I would get on our bikes and go out to cemeteries and go to the old part of the cemetery where the old graves were. The way they looked versus the gravestones of the fifties and the sixties, the lettering and the numbers were beautiful to me. And how it described how many years they lived and how many months, how many days they lived. Again, just who were these people? We even discovered kind of an abandoned cemetery in town that I think had just been forgotten. But somehow we came across this piece of land and just started kind of digging through weeds and all, and discovered this old cemetery.

Early Influences: A Grandmother's Sewing Room

Roderick Kiracofe: My maternal grandmother, who lived around the corner, was a seamstress and she had supported herself in her lifetime making things. At one point she worked, there was a glove factory in my hometown, but I saw her making neck pillows that she would sell at the church bazaar. She was also mending clothing. I think she also would be doing kind of just creative, little creative sewing projects, but nothing, no quilts, nothing major, but just, I would love to sit in her sewing room. She had an old Singer treadle machine, you know, pumping it with her foot. I think sometime in the early sixties it got electrified, and how excited she was to be able to just press a button on the floor that would run it. She wasn't having to pump her foot the whole time. But again, just the beauty of this old Singer sewing machine to me was fascinating. And to watch her making things with her hands, creating things with needle and thread. So that stuck into my mind, I think.

Discovering Auctions and Antiques

Roderick Kiracofe: In junior high school and definitely in high school, I started going to auctions at people's houses. Now they're called estate sales, but they weren't estate sales because there was an auctioneer. Somebody would die, an older person, the family would put everything out around the house, and an auctioneer would go from one thing to another. And I just found that fascinating. Again, looking at pieces that were old. Now I realize that was just the thirties and the forties. I wasn't seeing early antiques by any means, but I wasn't interested in fifties furniture. That just was too plain, too boring to me. It didn't have curlicues and all kinds of decorative things. So I definitely wasn't an early appreciator of mid-century modern.

Then there would be auctions out on farms and so I just, it was fun to go and see and occasionally buy something. I still have, it's like a maybe a five-gallon tin can that stored lard in it. It had this beautiful label on it. I still use it as a wastebasket. So just advertising was kind of a draw.

I never saw a quilt at any of those auctions. I learned later, like years later, from auctioneers that again in the fifties, in the sixties, even in the early seventies, quilts were bedding and no one wanted to buy somebody's old bedding. And if the family didn't take it, I mean old sheets and pillowcases and blankets, but quilts were just taken to the dump and destroyed because no one was interested. No one would buy old bedding, so I never saw a quilt.

The furniture was probably mostly Victorian. Again, this is northeastern Indiana. It just didn't have probably really nice pieces of furniture. My family had some chests, old chest of drawers that came on covered wagons from the east coast, but a lot of that just wasn't out at an auction.

First Encounter with a Quilt

Roderick Kiracofe: I never saw my first quilt until I moved to Los Angeles in nineteen seventy-three. I was kind of escaping the Midwest. It was also a period where I was kind of coming out, in or out a little bit, and then back in and out, in and out. But I kind of wanted to get as far away from the Midwest. So I go to Los Angeles, the West Coast, and my girlfriend at the time, who I'd met at college, she had on her bed a quilt that an aunt of hers had made from Wisconsin. It was a butterfly pattern. It would have been made in the thirties and possibly forties. Very pastel. But just these butterflies on it with embroidered antennae and just pastel, some printed fabric, some solid fabrics. But we slept under that quilt and it just reminded me of my grandmother. My grandmother could have made something like this. So it was that connection back to family history. Here it is in the Midwest and we're sleeping under it, putting in a washing machine and then the dryer. Over time, it wore out. It started to shred, and it just wore out.

Quilts as Art: A Revelation

Roderick Kiracofe: It was the following year. I had dropped out of college, was spending time kind of trying to find myself. What am I going to do with my life? I returned to school, a small private school in Pasadena, and an instructor, it was a school that really focused on early childhood education. It had been founded by Quaker families during World War Two. It was originally started as a daycare for working families, and then it evolved into this higher education. It was an upper division school. Plus they had started offering master's degrees, but it was in early childhood education.

The teacher that I was working with that first year, I was over at her house. So this was nineteen seventy-four. She had hanging on her wall an unfinished quilt top. It was a log cabin pattern. It was silks and velvets and satins. So an unfinished top. It's not quilted. It's not been quilted. There's no batting in it. There's no backing and it hasn't been quilted. It's just the top that has been pieced together. She bought that at a yard sale there in Pasadena and paid either five or ten dollars for it, and she had it hanging on her wall as a piece of art.

For me to see something like that hanging on a wall as artwork was just, it just burned into my mind of, oh, these textiles, these pieces of fabric that get sewn together can go on a bed. People can sleep under them, provide warmth and all. But hung on a wall and you see it from that perspective. It just amazed me. It just amazed me.

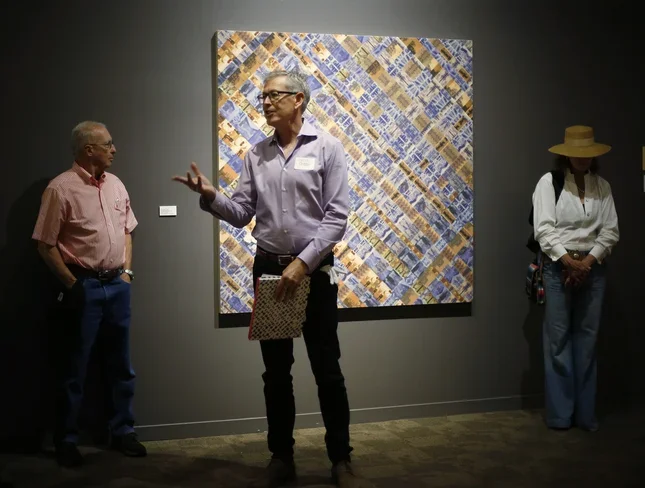

The Collector's Eye Exhibition

Hugh Leeman: I want to walk down this road with you a little bit more about this because you just mentioned something interesting. You recently curated an exhibit of your collection at the International Quilt Museum titled The Collector's Eye. What was it like for you to see these improvisational, often anonymous quilts, the kind of pieces that were long dismissed by traditionalists, now you're seeing them hanging in a museum gallery? What was that feeling like? Because here you are at that first experience of seeing it on the wall when you're a kid. Now you've donated and lent your collection to museums. How does that feel when you walk in? It seems like it feels very fulfilling.

Roderick Kiracofe: Oh, it totally is. It absolutely is. I'll jump back a little bit and I'll try to keep it, I can get long-winded.

Hugh Leeman: Please do the long version.

Roderick Kiracofe: Cut me off when you need to. But I then returned to the Midwest and was living in southwest Ohio, where my father was born. That was an area that had been settled much earlier. My father was brought up in the Church of the Brethren, and Church of the Brethren is an offshoot of Amish and Mennonite. So there is a quilting tradition among those church people.

I started going to auctions again. So this is now nineteen seventy-five, and this is just the beginning of when quilts are starting to be collected. They are appearing in farm auctions. People are buying them. They're collecting them. Dealers in New York and other big cities have started showing quilts as a collectible. And I see and I buy my first quilt at a farm auction.

Becoming a Dealer

Roderick Kiracofe: Fast forward. I have finally come out. I meet a guy who grew up with quilts. His grandmother quilted. He had quilts on his bed growing up. When I met him, he had a quilt hanging on the wall of his bedroom, quilt on his bed. So there was this sort of common interest, and we started buying quilts in the Midwest, first off, just collecting. And then a friend from college came to visit and we were showing him our quilt collection, laying them out on the lawn of the house and holding them up. He was amazed. He was impressed. And he said, "Have you ever thought of selling them?"

Well, no, they're special. We want to collect them. I am a collector at heart. But it definitely planted a seed. He came from a business background family, so he just, but he planted the seed.

Michael and I lived in Yellow Springs, Ohio, where Antioch College is, a very liberal, wonderful community. But we decided we're going to try going into business for ourselves. Are we going to go to New York where there's already a pretty big market, or are we going to go west? Certainly this is nineteen seventy-seven, seventy-eight that we're considering all of this. San Francisco is becoming very recognized as a gay Mecca. Primarily, gay men are moving, migrating to San Francisco. We decide we're going to San Francisco. We drive across country. The back seat of the car is filled with quilts.

The Dual Perspective: History and Art

Roderick Kiracofe: As we both got into it, for both of us, but particularly for me, I mean, there were two things that I carried with me. Again, it's that who made this quilt? Most likely it was a woman. What was her life like? Why did she pick these fabrics? How did she decide her quilting pattern and things like that? But then also knowing they also can be works of art. They can be pieces of art.

Two collectors, Jonathan Holstein and Gail van der Hoof in New York, had mounted a show at the Whitney Museum in nineteen seventy-one. Gail was the first one who went into Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, started buying Amish quilts and non-Amish quilts. She was fascinated by them, bringing them back to New York. They traveled in an art circle. They were showing them to artists. But the Whitney had an opening at the last minute in their schedule. They had approached museums. We want to show these as works of art on the wall. Whitney had an opening, contacted Jonathan and Gail and said, "Could you hang a quilt show for us this summer, like with just a few months' notice?" They do. Again, it's in New York. It's at a major museum. It does kind of take the world by storm. Then this whole collecting. So that's happening.

From Dealer Back to Collector

Roderick Kiracofe: A lot transpired. We became kind of successful dealers. But one thing that we did when we started selling quilts, we let people know we were not collectors any longer. Every quilt that we found and we were presenting to our customers to buy, we were not kind of taking the cream off the top, saving back some quilts. Everything was for sale. So I put my collecting kind of piece of me aside.

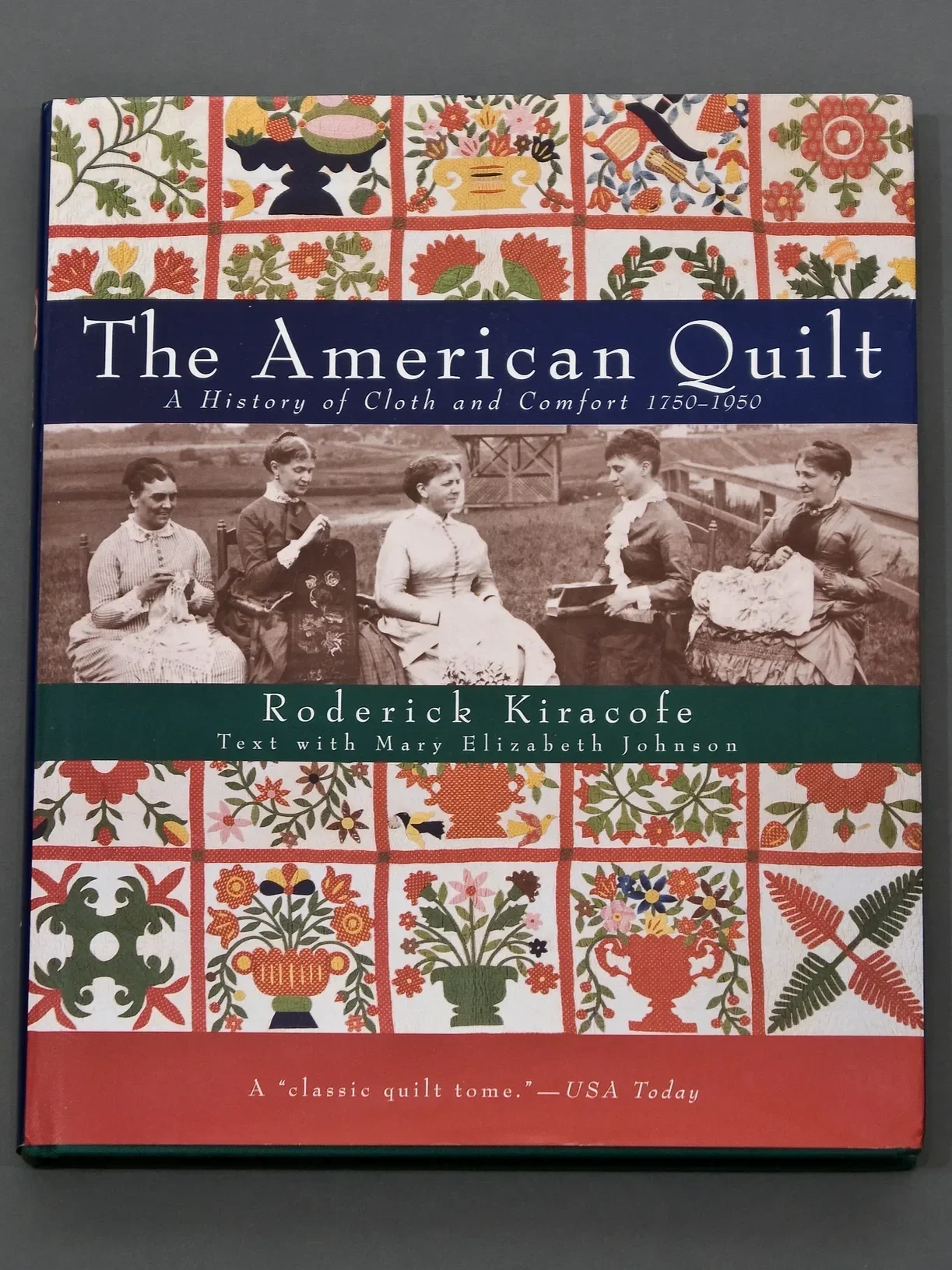

Jump forward twenty or so years. I've written a major book, The American Quilt: A History of Cloth and Comfort, which really looked more at the cloth, the fabric, the comfort of quilts, the whole textile industry, but showing this historical overview of America's quilts from seventeen fifty to nineteen fifty. The original plan was I was going to do a book, a follow-up from nineteen fifty on. That book just was not coming together. The pieces weren't falling into place. So I put it aside. I decided maybe I've said everything I need to say about quilts. I also realize I need to get a full-time job in my forties. It's been successful, but with any entrepreneur working for yourself, there's highs and lows. There is money, there isn't money.

Trusting the Eye: A New Adventure

Roderick Kiracofe: After a period of just hibernation, I got curious about the belief kind of among quilt historians that quilt making basically had stopped in the nineteen fifties, not to begin again until kind of the sixties, when a lot of back-to-the-land people and women who might have been studying art in other mediums kind of came to fabric and textiles and got interested in making quilts. So there were some early pioneer women who were starting to make quilts again, and making them pretty much as art pieces, not for the bed.

I got curious about whether or not that really did happen, whether quilts had stopped being made in the forties. And I decided I'm going to see if there are quilts out there kind of nineteen fifty on that just appeal to my eye. I've been told for decades, people like, "You have such a great eye. You have such a great eye." And I go, "Well, I didn't study art. I don't come from an art background." Like, "Well, no, I couldn't possibly." Well, I did, and I do, from just kind of training, learning myself.

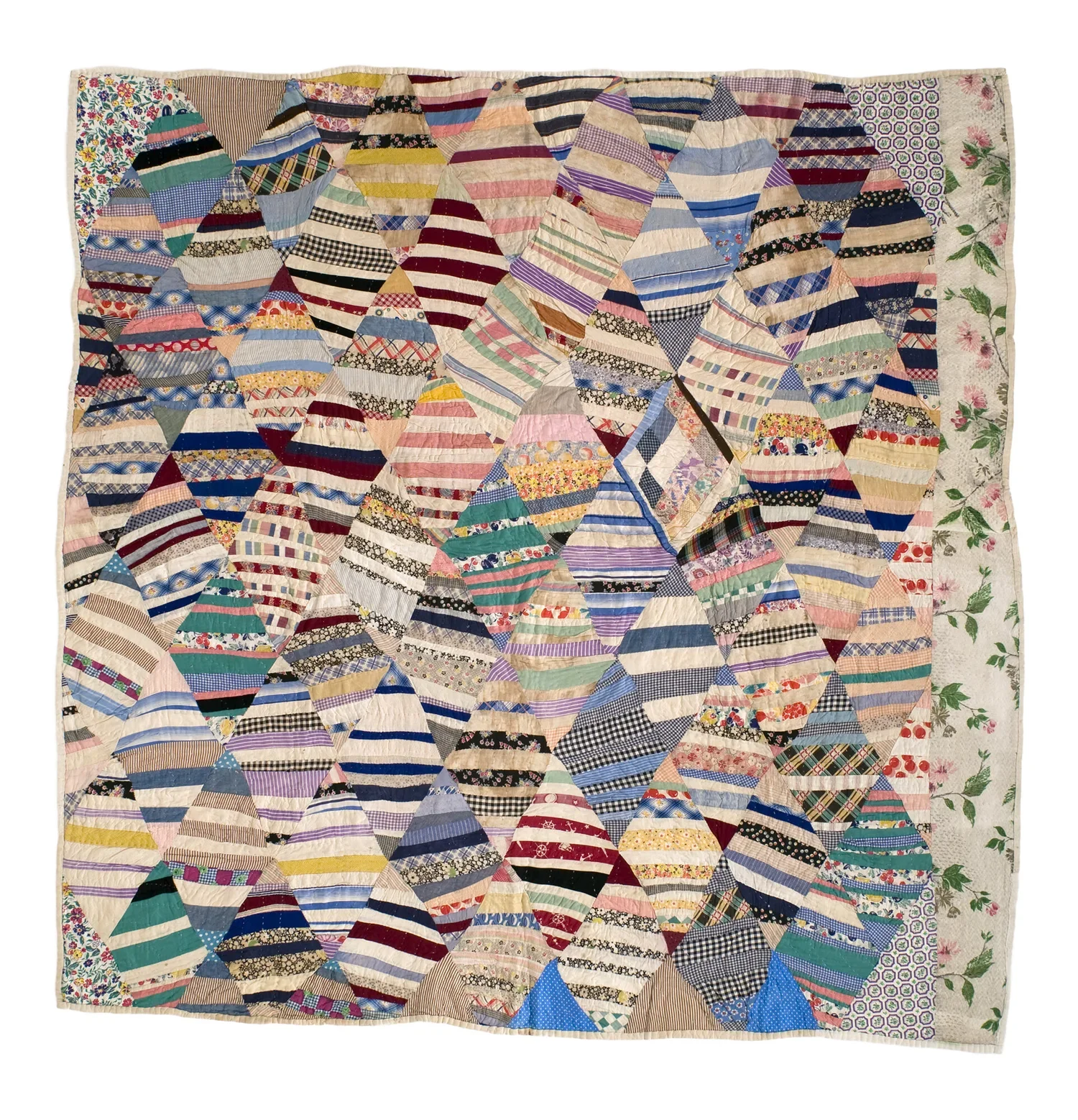

I decided to go on an adventure of trusting my eye, looking for quilts that just appeal to my eye or aesthetic, and more so I leaned into, might these quilts, do they affect me as a piece of art? Any time I found one, I did try to get as much information on the maker as possible. That wasn't always available. I had thought by, this is early two thousand that I'm starting to do this, I thought there were just so many books there. Almost every state had done a quilt search and a documentation of quilts within each state and getting all the information, getting makers' names and all of this.

So I was really surprised when people said, "Well, why would you want that?" I go, "Well, it's nice to know a maker's name, particularly in this day and age." Like the maker still could be alive. So I tried to gather and I did gather that as much as possible, but I really was just looking at them from kind of this art perspective.

Discovering Treasures

Roderick Kiracofe: I started finding one and then another, then another, then another. They would be shipped to me. I never saw them in person until the box came, and I opened it and put it on my studio wall and would stand back from it. And nine times out of ten, I just was in awe of what was hanging on my wall, what I had just purchased. Just being kind of blown away by it.

I had a lot of artist friends. I wasn't telling too many people in the quilt world what I was doing. I was kind of traveling below the radar on this project, showing them to artist friends, and they were all just, "Oh my gosh, oh my gosh, these are incredible." And or, "Boy, that looks like so-and-so's paintings, that looks like so-and-so's paintings." And I thought, I am on to something here.

When I started this project of looking for quilts and buying quilts, it was always my intention from the very beginning, if I found good things that I felt were important, and by this time in my life and career with quilts, I mean, I had seen thousands and thousands and thousands of quilts. But if I'm finding things that I feel are really good, I do want them to go into museums. I want them to be hanging on museum walls. So that was a goal.

The International Quilt Museum

Roderick Kiracofe: I don't always remember exact dates. It was pre-COVID that I know. International Quilt Museum had gotten established by two collectors, a husband and wife who had graduated from the University of Nebraska. They had shopped their collection around to a number of museums. They lived in New York. They offered them to the Met. Now they had thousands of quilts. This wasn't just a few hundred. This was thousands.

Hugh Leeman: Wow.

Roderick Kiracofe: The Met has an incredible quilt collection and overall textile collection, as do a number of major museums in the country. There are quilts in their storage vaults. So they came to realize that one museum couldn't digest this many quilts. So the idea came that, okay, we're going to start a museum. And they went to the University of Nebraska, where they had connections. They basically funded it, and the building of what was called the International Quilt Museum.

I was familiar with these collectors. I got involved peripherally with the International Quilt Museum, but always felt like, okay, this is one of the museums that I would like to see my quilts in. I also was going to major museums around the country, showing them my quilts, offering first to exhibit them, then for acquisition, either purchase and or donation.

I approached the director and curator at the International Quilt Museum saying, "I would really like to put a collection there at the museum." Of course, they were thrilled. Of course. We worked out the grouping. They picked some things. They said, "Well, you pick also pieces that you would like to include." So it ended up being originally it was thirty-five, but I sent one by mistake, so it was thirty-six. And I said, "Oh, just keep it." I just kind of forgotten on some level about it. So it was a part purchase, part donation to the museum.

The Collector's Eye Exhibition Opens

Roderick Kiracofe: Now here in twenty twenty-five, they organized this exhibition. I did not go to them and say, "Let's do an exhibition." Of course I have said at some point I'm really eager for you to show my quilts. A few quilts have been shown in other exhibitions that they've organized, but they started doing what they're calling The Collector's Eye. And so this one is The Collector's Eye: Roderick Kiracofe. And they picked a group of quilts from what is known at the museum as the Roderick Kiracofe Collection.

People go online, you can go through, I forget how many collections they have of various people and of various types of quilt. But one can go to the website, go online and look at those collections and see all of the quilts.

Bringing Contemporary Work to the Museum

Roderick Kiracofe: I then became a part of a kind of an advisory group to the curator about bringing in contemporary work. They've been acquiring contemporary quilts all along, but I was bringing to their attention, "Well, you know, there are a lot of artists who aren't in the quilt world who are using quilts now in their work." So I wanted to bring those to their attention, which I did. I started doing, and in some cases I helped acquire pieces. I donated funds or I helped negotiate a lower price on it to get this kind of contemporary work into the collection.

Now, what I was thrilled about when they told me we're doing this Collector's Eye: Roderick Kiracofe, with your collection or pieces from your collection, we're also including contemporary work that in most cases you helped to bring to the museum, and that the artists of that work either credited me with inspiration, of just the body of work that I had done up to this point in terms of getting all kinds of quilts exposed and out there into the public eye through other publications that I started myself or with a former partner or having.

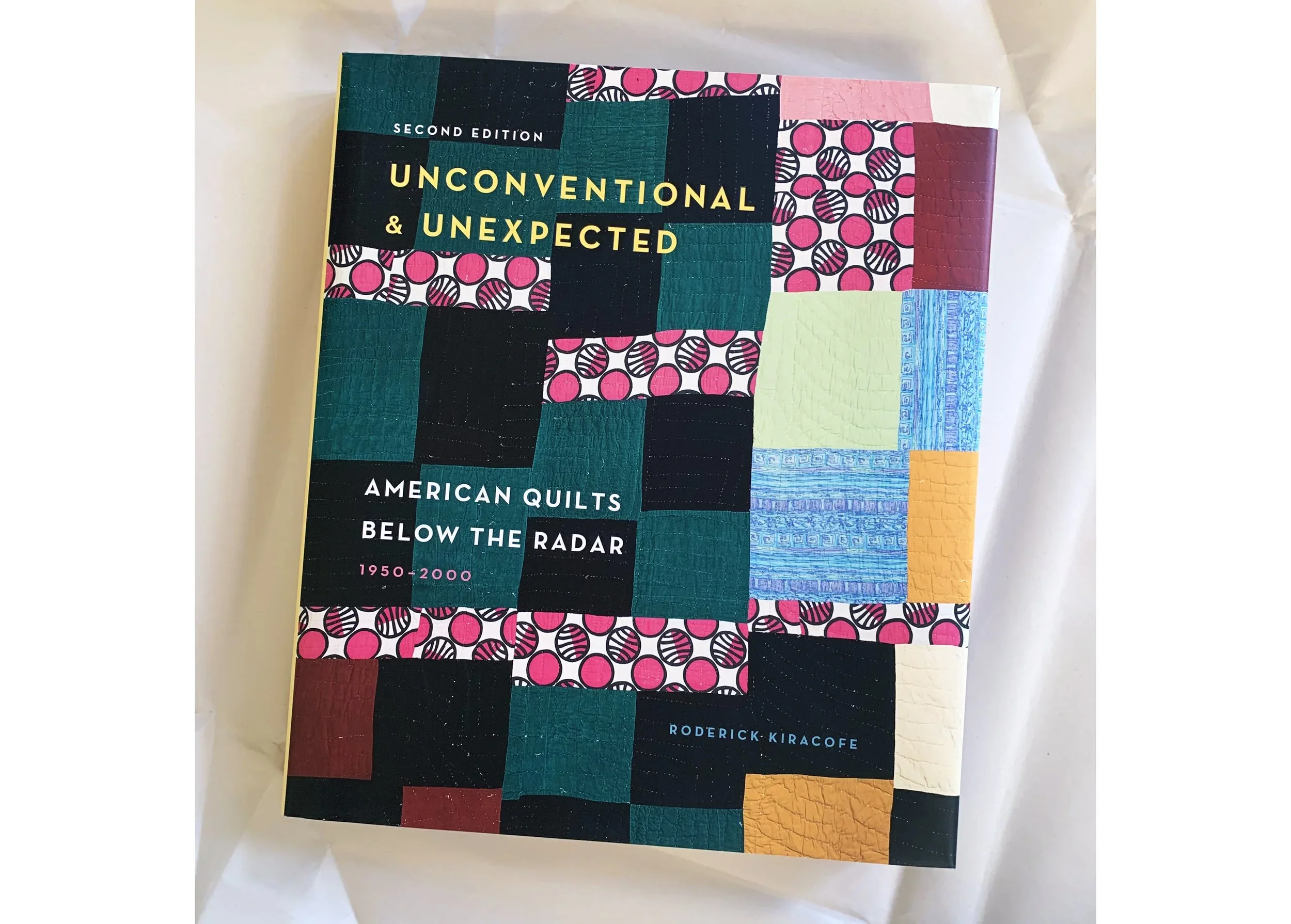

I've been very fortunate for the most part with having publishers come to me and say, "We would like you to do a book for us." And so this collection, the most recent collection from what these quilts are drawn from, were in a book called Unconventional and Unexpected: American Quilts Below the Radar, 1950 to 2000. And I did show and bring to the attention of the quilt world and a bigger world because lots of artists say to me, "Your book is such an inspiration, whether I'm painting or I'm weaving or whatever, it's just the quilts in this book have given me so much inspiration."

I mean, that's exciting. Anytime somebody puts work out there into the world, you want to appreciate it, but not everyone is going to. But it's exciting when a pretty large audience does respond. And it did. I've seen a lot of work that appears since then that I can just see a direct connection to. It's expanded the possibilities, I think, for people.

Challenging Traditional Standards

Roderick Kiracofe: Where in the past, a quilt that wasn't perfectly made wasn't highly thought of, yes, there has been some collectors all along that have seen the beauty in that. But as a general rule, people like things that were perfectly made and perfectly quilted and were perfectly square or rectangular. And a lot of the quilts that I've found are just, I mean, they're misshapen. The pieces don't fit together perfectly.

I've always liked a tied quilt. That's where the maker used, it could be string or yarn or all kinds of thread, where they're not quilting it, they're just tying the front and the back with the batting in between. And these ties appear on the front. Those were never really thought of as collectible. Well, I started finding pieces that were just amazing and just like, you know, a tied quilt was a utilitarian quilt. A maker could make it really quickly and get it on the bed and keep people warm. But I was finding quilts that had thousands of ties on them.

One quilt in particular had all orange ties, yarn, polyester yarn ties that literally covered the entire front. When I saw the picture of it online, it looked like it was on fire. It just was so blazing orange. It's just so unique. It's so odd. What caused that woman to make it that way?

The Cultural Shift Toward Textiles

Hugh Leeman: Well, Roderick, you've been part of this shift. I mean, what you're saying here in our conversation is very interesting because, as you noted, you go back a handful of decades and oftentimes quilting has not been seen as a fine art that belongs hung on a wall in an institution. And you have been a part of that shift. But you very interestingly noted in one of your previous interviews that you see this shift taking place at an accelerated rate. What are the cultural components that account for this shift that it's becoming not just with quilting, but textiles, more acceptance in institutions?

Roderick Kiracofe: Well, I don't know that I necessarily have the answer. I never thought I would see in my lifetime the amount of interest in both from the artist, the maker, and then contemporary galleries and now museums in contemporary textiles.

Early on, if you approached a gallery like in the seventies, eighties, nineties, like, "I'd like to show quilts or some kind of textile," well, "Oh, well, did your grandmother make them?" I mean, that would be the attitude of, "Oh, isn't that quaint? Isn't that cute?" So crafty and that kind of attitude. And there were a few galleries around the country where a gallerist would have a particular interest in textiles and would have a few artists, but it just was very rare.

A quilt museum or a museum may decide to do an exhibition of their quilts. Certainly there was a huge interest in Amish quilts. And so there was Amish exhibitions. But if you approached them with another idea. And whenever a major museum mounts a quilt exhibition, their attendance is enormous. They bring in an audience that may not necessarily always come to that museum. But if it's quilts, people come out of the woodwork. It's just, it's been documented. Their attendance just skyrockets. But you approach a museum with another idea for, "Oh, well, we did an exhibition of quilts two or three or ten years ago. It probably won't happen for another."

A Generational Shift

Roderick Kiracofe: In the contemporary galleries, there was not interest in there being fabric involved, textile weaving, a patchwork of any kind. And then again, there have been some real pioneers, all women, few men, in the quote world of women who were weaving and doing work with textiles, who were recognized. But as an overall, it just was difficult for an artist to try to get their work seen and be appreciated.

Somewhat has to do with just a younger generation, another younger generation of artists coming in. I found that with people that I was meeting in San Francisco going to the Art Institute or CCA, where they said in the seventies, eighties and nineties, you said, "Well, what do you do?" "Oh, I'm involved with American quilts." "Oh, that's nice."

I started meeting young people in their twenties and thirties, going to art school, and the reply was, "Oh my gosh, I love quilts. They're so cool. My mother made, my grandmother made quilts, but they're just, I love them." So it was just interesting in observing that shift happening.

Contemporary Artists and Quilts

Roderick Kiracofe: Just starting to see in the galleries, I mean, one name that comes to mind is Sanford Biggers, who started painting on quilts. Now, there are a lot of people that were horrified by that kind of, I mean, in terms of in the quilt world, there can be a preciousness about a quilt. It shouldn't be slept under if it's on the wall. I mean, you do want to protect any kind of textile. They are more vulnerable if you're hanging them on a wall, whether it's a home wall or a museum wall, gallery wall.

In terms of quilts, it happened prior to that. Again, I think maybe in the eighties when a couple of clothing designers, I think Valentino was one, and Ralph Lauren at one point started making clothing, kind of high fashion out of old quilts. And people were horrified. "You're cutting up a quilt." Now, no one wants a really rare quilt to be cut up or something of historical value, but millions and millions and millions of quilts were made and then quilt tops. And I found it exciting to see, well, this is getting out. This is getting quilts out into kind of a larger public in awareness, in front of more and more people.

So then Sanford Biggers starts painting on quilts. I mean, first it was like, "Oh, wow. Oh, wow. Oh, that is so great. That is so cool to be using a quilt that otherwise may get thrown away or just stay folded up in a closet, never used." And here's this contemporary artist painting on them, and now they're in major contemporary art galleries.

Whether it's going to a fine arts MFA student show of their work to going into more galleries and just seeing textile work everywhere. And as I said, I just, I never thought I would see it in my lifetime.

Quilts and American History

Hugh Leeman: Roderick, you mentioned something really interesting in this. You mentioned the historical aspect of that. And so I want to hear your thoughts on this, because there's such a rich and deep history with quilting and even the symbolism in it. You wrote a book, The American Quilt, and one review that I read of this, the reviewer wrote of your book, quote, "Ingeniously, it weaves the threads of America's social, political, economic, and industrial history into the evolution of the quilt-making arts," end quote. How can a humble quilt block or pattern open a window into, say, the Industrial Revolution or the Great Depression, or even other historical themes that are widely established as being connected with quilting, such as American slavery?

Roderick Kiracofe: That's a big question. Where do I begin with that? I wanted to present the American quilt again in this, I'm blanking on the word where it goes year by year, decade by decade.

Hugh Leeman: Chronological.

Roderick Kiracofe: Chronological. Yes. I work that way, and it's easy for me. And I looked around and there had been other major quilt books written, but there had been some time, but no one had arranged it that way. And I like to see a book, whether it's on an artist or anything, showing it kind of from a beginning point, taking it through. How has that artist evolved, or how has this medium of quilts evolved over centuries?

And then to then go a step further, start it with the production of the fabric, the different types of fabrics that were made and used and available to women in their quilt-making. Again, I mean, there have been books written much more in depth on all of these things than I do. I think I'm somewhat more of a generalist. I mean, I do as much extensive background research as possible of what's out there, what's in the field. But since then, there just have been, Amelia Peck at the Met just did this incredible book and exhibition of just the whole textile industry around the world and how it, the effects on so many things, the economy and certainly slavery or about textile, cotton growing to go into textiles. There are just so many different aspects of it.

Quilts as Community and Fundraising Tools

Roderick Kiracofe: Certainly, I mean, how quilts were used throughout. They were used as fundraisers for churches. They were used as fundraising for the Civil War. They were made to be sent for injured soldiers.

Hugh Leeman: There's something I've read that I'm curious to hear your thoughts on it. And it's not entirely established as an objective fact, but that there were symbolism woven into some quilts that was connected to the Underground Railroad and that these would be shown in some way so that someone that was in the process of escaping slavery could know where a place of safe harbor was, so to speak, via these quilts and symbolism. What are your thoughts on this?

Roderick Kiracofe: Well, there is a lot of controversy around it. Misinformation has been published as fact. I think it's primarily an oral history, an oral story, that wasn't written down. And so it has gotten, other people later have made interpretations that may not be completely accurate. Some of the books have shown specific patterns that had not been used yet in quilt-making at the time of the Underground Railroad. It's how quilts fit into that. Sure. If they did, how they did. No one has written the definitive story, because, again, I don't think it's possible to. Because it's such an important history and story that exists of how people were helped. People were helped. Slaves were helped to get to the North. Organizations that were working on that and doing that. But was there an actual quilt hung over a fence? We just really don't know for sure.

Contemporary Political Quilts

Hugh Leeman: There's something really interesting in your most recent book that you mentioned as well in our conversation, The Unconventional, Unexpected. In this, you say, quote, "I always wanted to do a book that would continue the story of the American quilt and show what happened after nineteen fifty," end quote. What are the quilts that are being made today showing us and reflecting about the social landscape of our moment?

Roderick Kiracofe: There have always been political quilts, but I think today there are even more. I love seeing the contemporary quilt makers who are making political statements now on all kinds of topics. A woman's right to choose, gun control, war. I'm not sure if I've seen yet an anti-fascist quilt, but I'm sure somebody has or will. But that's exciting for me to see. And again, I feel like there's a lot more being made now. Again, I have no idea how many were made in the past that didn't see the light of day, were destroyed, no longer existed.

But I just think maybe there's more permission now for primarily, I'm speaking, the majority of quilt makers are women. There are more and more men making them, and then women from various cultures. I think there's just the permission to be able to express their horror, outrage, in some cases, joy and excitement about certain things in their life or in society, but not having fear about voicing their opinion about political topics that generally are controversial, but they're putting them out there.

The Power of the Quilt as Medium

Roderick Kiracofe: There's just something amazing about, I mean, again, people can have when you say the word quilt, what's their impression? "Oh, wonderful blanket, handmade on a bed." Again, "My mother made them. My grandmother made them," whatever, just that connection. But then to take this textile that has that image and thought about it of, it provides warmth, it provides comfort. And, oh, it's talking about how many bullet holes are on this quilt that has been made that represent how many bullets are shot in a short period of time in a schoolroom that have killed children.

Hugh Leeman: Wow.

Roderick Kiracofe: Or again, the right to choose, a woman's right to choose. To me, it's just, it has a power to it. It's more than just a sign in a protest. It's a sign, which are wonderful. But when it's on a quilt and then that quilt can be shown at someplace like QuiltCon or in a gallery or at a museum, it's pretty powerful because at some level it may be a way in for people. If it were just a sign at a protest, but oh, this is a quilt. And to be thinking of just kind of all of the many meanings and layers of a quilt, but it's presenting me this really strong message to make me stop and pause and think about. And again, some people can walk by and dismiss it. But I feel like it does give more of an entry point.

Looking to the Future

Hugh Leeman: I want to ask you a final question here, because you've brought up some very interesting points about the history of it, but particularly your involvement in this shift from it being seen as a utilitarian object that was meant to keep someone warm, to going to, in no small part thanks to yourself and your scholarship, as well as your collection, to being hung on museum walls. With those ideas in mind, what is the greatest ambition of where you hope quilting goes from here?

Roderick Kiracofe: I just want to see it continue and flourish and just all kinds of new ideas that I never thought about. The next generation, then the next generation of taking this medium and just, there are hundreds of possibilities. There are millions. There's infinite possibilities of what I could do by sewing fabric together. Statements that I can make or just or designs that I'm inspired by, or a unique way of showing them.

They are more and more becoming sculptures. It isn't just a flat object, either on a wall or on a bed, but becoming more sculptural and the kinds of materials, making them out of metal, making them out of wood, making them out of plastic, bringing that whole awareness of where does all this plastic go? It stays. It doesn't go away, it stays here. But yeah.

And again, painting and also now there's much more focus again. And I think it's more, it's lasting longer. It's not just a passing fad about patchwork clothing, whether it's jeans that have patchwork on it or a dress or a shirt or a sport coat that's made out of an old quilt or a quilt top, whether it's recycling that, or people taking recycled materials and doing it in a patchwork fashion. Again, kind of this whole new phenomena that has staying power. And I think it's going to just keep going and going as people let their minds and imaginations fly.

Closing Thoughts

Hugh Leeman: This is wonderful. I admire your optimism and the dedication that's not been one or two years, but several decades contributing to being a part of this change of how society sees textiles. So thank you so much.

Roderick Kiracofe: Yeah, you're very welcome. It's been again, just kind of this unexpected thing for me, what happened in my own life around them. But the ability to have an opportunity to show this to the world and have it so well received and then just see those ripples continue on. It's incredibly satisfying to me. And it's exciting to see where more people are going to take it.