Porfirio Gutierrez

Porfirio Gutiérrez is a Zapotec-American artist based in Ventura, California. He uses traditional Zapotec technology of pigments and materials and redefines Zapotec weaving language to create works that communicate contemporary experiences and the complexity of the Americas today.

Gutiérrez's expertise is based on a family legacy of treadle loom weaving and ancestral knowledge of organic materials and seasonal cycles that result in an unlimited palette of natural colors. Through his practice, he asks us to rethink narrow definitions of contemporary art and indigeneity.

In 2015, he received the Smithsonian Institution's Artist in Leadership fellow, in 2021, he received the Carolyn Glasoe Bailey Foundation Art Prize, and in 2023, he was a finalist for the Frieze Art Prize. He has taught materials and color at Harvard University, and serves as a Fellowships Advisor for the Smithsonian.

His work is in the collection of LACMA, the Los Angeles County Museum, the Smithsonian's National Museum of American Indian, and the Tucson Museum of Art. A selection of Gutiérrez dye materials was also documented and added to Harvard Art Museums' Forbes Pigment Collection, the world-renowned archive of artist materials. His work has exhibited nationally and internationally, including at Chinati Museum, Black Mountain College Museum + Arts Center, Sharjah Institute for Heritage, United Arab Emirates, among others.

The following are excerpts from Porfirio Gutierrez’s interview.

Hugh Leeman: Porfirio, you grew up in Teotitlan del Valle in Oaxaca, Mexico. In a previous interview, you said that you only realized the richness of your culture after leaving Teotitlan del Valle. How did living abroad change your perspective on Zapotec weaving and culture? And what did returning home teach you about yourself?

Porfirio Gutierrez: I think by removing yourself or your being removed from your community and a community that's such a tight community, a place. By the time I was growing up, it was a place where almost everyone knew each other. It could be really hard to really be aware of the environment also, because at that time I didn't have any other reference other than the community and very little, like the city. We didn't spend a lot of time in the city, so I didn't have a lot of other other references. And by removing myself, from that community, that has allowed me to recognize the richness and the importance of of my culture and the environment that I grew up. and so by doing so, I was I was able to, to be mindful of it.

HL: This culture and community that you're referring to. If you could give maybe some context here, because it has such an incredibly rich history and ancient, rich history, as well as being incredibly influential in the Americas. So the zapotecs going back to say, Monte Alban and even before San Jose, Mogote. And then in addition to that, you speak Zapoteco, can you outline who are the Zapotec people and how do these ancient cultures and cosmologies influence your art?

PG: The Zapotec people. Are these a particular civilization that has been living in the Central Valley and then later on spread out much more beyond Central Valley for at least ten thousand years? It is a culture that has developed a writing system. Mathematic, of course, so many things, so many art forms, uh, spiritual aspects of of what's really important for them and still is really important for us. They've also, are maybe the or one of the culture that, domesticated a wild plant today known as as corn. another really important and contribution of this civilization was the the domestication of cochineal insect, Dactylopius coccus, or the as we know it in our native language. These are insects that are breed on prickly pear cactus to produce the red color historically was also used for medicine and other ceremonies and rituals. And so that that gives us a little bit of, the how do I say the, the, the not only their contribution, but also, the work that they, as nation has done to develop such a great civilization that also had a influence, especially through the cochineal insect influence the world through that.

HL: I want to come back to the cochineal later. And as it relates particularly to your collection of natural dyes. But first the weaving. Weaving from a lens of art has oftentimes been seen as a craft and not fine art. Yet in an interview with the Spanish press. When you finally exhibit your work in a museum, you said that you began to realize that quote, what we do is art. How did institutional recognition affect your self-perception as an artist and then influence how you communicate the value of Zapotec textiles?

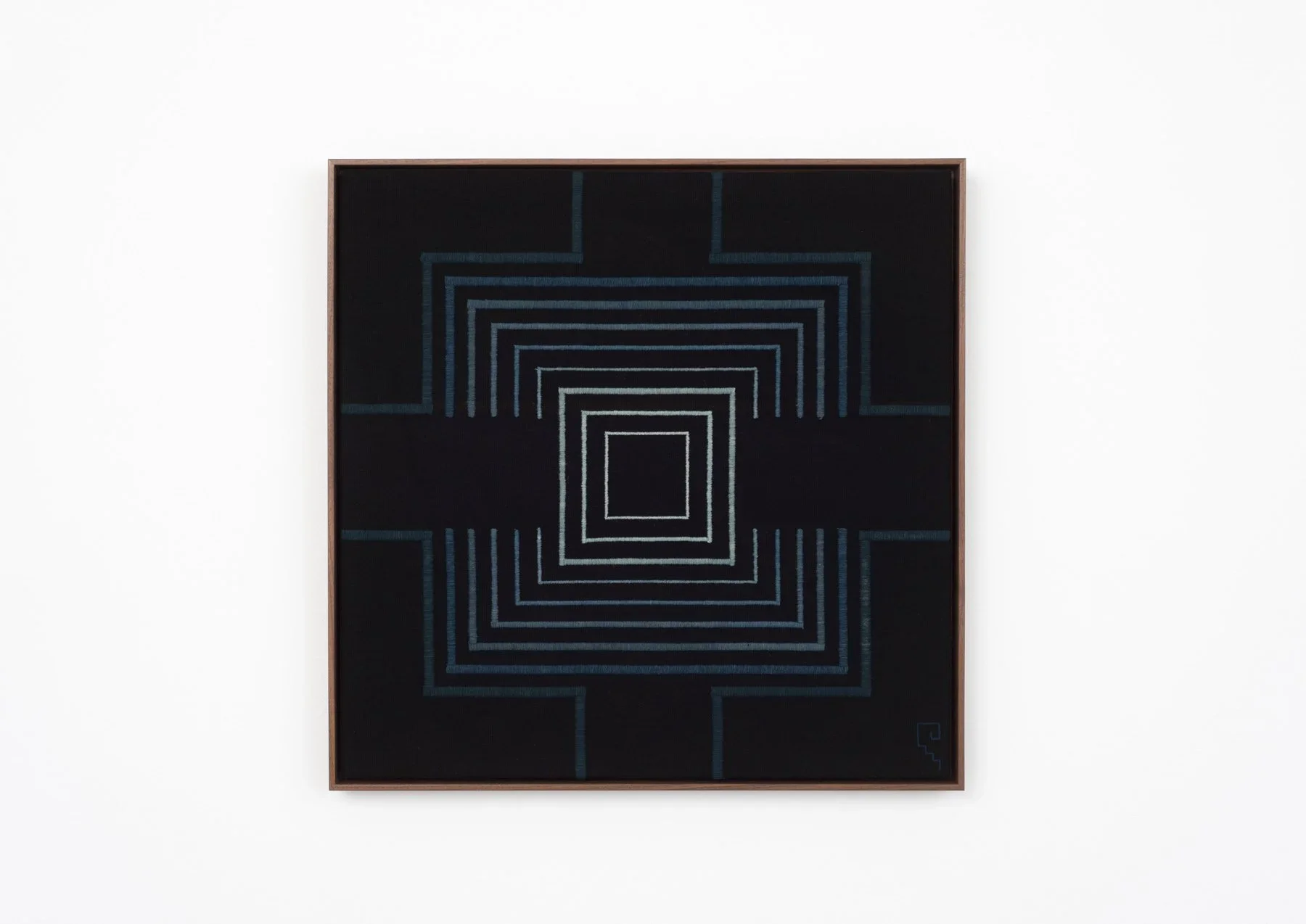

PG: Yeah, I think, uh, you know, for me, uh, especially engaging in, uh, tradition culture, uh, ancient, historical, uh, present, uh, migration, uh, all this complexity and all these different layers of, of identity that I carry today has obviously, has been, uh, an enrichment, but also a great deal of, challenge for us to be able to, poke through the system, a system, a Western system or an education or around the arts and everything that's around that, has been placed. and that, eliminates us. has not invited us to, to be part of a meaningful conversation. Right. So it has been extremely challenging. It's hard for me to be able to engage in that, uh, excuse me, in that space. And I want to start and end with this. Is that in our native language, there isn't a word for art. Ah. And and and the and the education around art. We know that it comes from Western education and view. But that's not the only way of understanding creative. That's not the only way. And so the challenge starts there that this system only recognizes their own education and system when it comes to to art. And within our community, the closest, uh, translation will be someone with wisdom. Someone that's, that serves the community. Someone's that, has responsibility to the community and to the ancestors and specializes on something. Right? And, historically. Historically, it was maybe someone that maps the community, someone that writes the story, someone that what we they know as science that works with medicine and plants. Uh, maybe what we know today as priests, someone that's the spiritual leader of the community. So someone that's respected and and holds wisdom. And so, engaging in the art world or the contemporary art world, a place where sees my work as craft, a place or a system that sees my work as a, nothing that has valuable other than, uh, a research material. has, not only, uh, placed the community in a different category and does not allow, uh, them to be part of a larger conversation when it comes to art, but also, it has, you know, put us in a, uh, a place or a, a confined space where that is the only place we could exist. And and we're not supposed to play any role beyond that. my idea or my approach to this is that in so many ways, I met them in the middle. Meaning is that some of the work that I'm doing, especially in the continuous line series, they are framed. They are drawn from geometry, abstract work that my ancestors has been doing for all these, what, ten thousand plus years? What we know today is geometry, of course. I have that that landscape continues to be my source of information to make. But by framing these work, uh, the Western or the system or the, uh, institutions start to pay attention to what I'm doing and are saying, oh, I think there's something here. I think this gentleman is an artist and not a craftsperson, but that was my way to force myself into the system. Uh, by meet, meet, meet them in the middle.

HL: This idea of meeting them in the middle and between the spectrum, so to speak, of the so-called fine arts and crafts. And you are doing something quite fascinating here. So you've emphasized that exhibiting a broad brings with it this incredible responsibility of effectively saying, I am Zapotec. I come from millenary roots. What responsibilities do you feel as a cultural ambassador, and then how do you balance this idea of sharing your cultural heritage while also protecting it from exploitation?

PG: Wow. The responsibility. I try I really not think of myself as an ambassador. I think that's a big responsibility. But whether I, I welcome that, whether I think of myself in that way or not, I am someone that has responsibility, especially to my own community. And to my ancestors. See my ancestors. At one point they made offerings. They made, uh, ceremonies. They prayed, uh, pray, offer their prayers to the greater Being, uh, and ask for, uh, me to be here today. And so the responsibility is even greater there than than I can even think about. Because at the end of the day, I'm actually doing their work not just so much as my work. Right? Because they're the one that started this work. I'm just a conduit. And so the work that I'm doing, it embodies their spirit. That is a way for the spirit to come to life. It's not just my work. It's also their work. Right. And since they come from the community, there's nothing that could be done with. Not the community collectively. Right. And so that in that sense, when I think about it that way, oh my God, it does makes me a little bit nervous because of the responsibility that holds and how I move forward as an individual with, uh, experience more contemporary experiences like migration, uh, political issues that we're facing and living in a country where, uh, persecutes people like that looks like me, that just that adds another layer and another layer of our responsibility to be able to communicate a different perspective of what all these things means to us and to communicate in a non-linear narrative. Right? And to be able to present, present a different truth to the same story, because it's not just one, right? There's several of them. And to be able to, uh, with understanding this responsibility has allowed me to, uh, raise voice when I see things that are being, that are being wrong to our culture, right, that are being, uh, if there's an exploitation. we are exposed to that every day. Right? It's these, extraction, right, of so many things, even, you know, when colonization took place, they were after goals. They were after silver, they were after. And now it continues to happen. But now there are after, you know, they still see the same value of our traditional knowledge, traditional medicine, the food and ceremony and so on. So that continues to happen. So, uh, but by understanding the responsibility and operating from these more neutral, space allows me to, uh, to raise my voice and to, uh, to engage in conversation when I see there's something wrong happening.

HL: You take this to a very interesting familial level that I'd like to get to in a minute here, but for a bit of context, you are well known for collecting natural pigments from nature, as opposed to using synthetic dyes in your artworks. Of this, you once said that your family decided that, quote, its legacy must survive. It's something much more important than money. End quote. How do you balance the commercial success that you're having with non-monetary value, such as spiritual and cultural values that you want to pass on to future generations once you become an ancestor, so to speak?

PG: Yeah. You know, there's this thing that, uh. There's things that it could not be sold and there's things that I could not charge for, uh, the natural dyes, the colors, the my art material. Maybe the majority of them are not purchased. It's given to me by by nature, by God the greater being, it's given to me. And so by me charging a small fee for those works, uh, I'm just exchanging for me to be able to, uh, participate in the economic and transitional, environment as contemporary artist. Right. So I have to do that. But in so many ways, you are is I'm actually just allowing them to care for the work. Mhm. They are these things are never are, never can never be sold. If this thing does not have a price but to participate in that, there's a small fee of exchanging to, to my creative, to the materials for the ancestors in the community. And uh, at the end of the day, these works are a life. These work hold spirits that cannot be, uh, horror, you know, that could not be, uh, collected. And and any institution can understand that at the end of the day. there could only hold it for a certain amount of time.

HL: Mhm.

PG: As much as we want to, uh, uh, possess of possessing the object forever, that's never going to happen. You know, these are living materials and, uh, and those are where these two world clashes, right, of one that is obsessed of permanency, another one that understands the cycle.

HL: Yes. I want to go back to some of your childhood. You have this incredible connection, as you're noting here with the collection of the natural pigments. But you also said earlier the idea of the cochineal and the coaching needle not only is a pigment, but was used as medicine growing up. Your mother was a healer. How do you see weaving and dyeing of the artworks intersecting with traditional medicine and wellness practices in Zapotec culture. Today.

PG: It is very common, Hugh, that if you look at the cultures around the world, but especially in our in our community, in our culture, it is very common to see the intersection of food, medicine, ceremony and traditional medicine. They live together. In fact, if you look deeper, science, chemistry lives also within, within the community and within the knowledge. Right? So it is something that it's very natural growing up, uh, because I was always part of it and because and and because I also come from a family, uh, mom and dad did not ever, uh, had the opportunity to, to be educated in the Western world. So their education in so many ways, uh, preserve its integrity because it comes from the ancestors education. Right. And so by being being raised by these parents, has helped me tremendously, uh, into, being connected to that understanding, to that education, to that, uh, way of existing, uh, since a childhood, since before I was even born. Is, is that the, and a very true and authentic way of, uh, of of who we are as human and family. I do believe and hopefully that is, that is communicated through my work.

HL: Sticking with this, uh, experience in the childhood and the influence, it's a beautiful story that you've told. And connecting with the cochineal that you recall as a child herding sheep that you pinched cochineal insects on cactus pads, then used their dye on your slingshot and your hat. Can you talk about what cochineal is for? For those who may not have context in the deep history of cochineal. And then you mentioned earlier something very important here about its role in global trade. What is the importance of cochineal and, say, Zapotec culture? But even in the in the Americas and then international exchange.

PG: In cochineal insect was one of one of the very valuable and important element within the culture, uh, because its usage today, we, we, we see a little bit of resurgence, especially in the natural diet practices, uh, with textile and, for someone like me that only uses natural pigments and elements for color, what is the. That is the only source for for for color. So if I, if I have, if I would like some reds and anything that comes from, from red, any color that comes from red, well I need cochineal. I need the cochineal insect. So if cochineal, if it's affected, let's say for one season and uh, will be, uh, if there were a shortage of these, uh, cochineal insect. Well, you won't see any reds in my work. And that's how crucial. And that's how important it is today. But historically, historically uses medicine using different ritual has, has clarified my questions that why a civilization, took their time to genetically modify an insect to today known as Dactylopius coccus. Why? They they they had to invest all that money. And I mean, not money, but time and knowledge. Right? And I could imagine this had to happen in many generations, not not just one generation. So that domesticate them and and yes, probably because it was used again, different rituals, ceremonies and as medicine and of course in the arts. What is cochineal insect. Cochineal insect is a female insect that are, that are, uh, grow wildly in a desert semi-desert environment throughout the Americas. Here in Ventura, where I live and where my studio is. You have cochineal throughout our landscape here. They love this kind of, uh, this kind of environment and, the through the, through the domestication of this insect, that's how that's how it became what today known as dactylopius coccus. And, it's a female insect that are, white fuzzy, dots, balls. They're so small that you might see on your cactus. Depends where you live. Live? And, that is the cochineal insect. it's an they they could. The wild insect kills your cactus even though it continues to receive. Even though the plant continues to receive nutrient nutrient in from the ground, it'll kill your insect. So it's a,

HL: A pest.

PG: Exactly. That's exactly. It's really hard to get rid of. Uh, Ironically, the domesticated insect will not kill the cactus. Or never kill the cactus. So there's these, again, beyond explanation to what all this thing is, right? And that the ancestor understood what what it is and how to work with it in harmony versus just seeing it as a commodity.

Speaker 3: Mhm. Mhm.

HL: This idea of working with something in a sustainable way. You, you take this even in a familial behavioral pattern with your incorporation of your family members and your studio, and you've highlighted that even finishing a piece like you give an example of your niece tucking in loose ends at the tucking in of those loose ends on one of your finished artworks is an art in and of itself. How do different family members skills contribute to one of the finished artworks. And what is this collaborative process? Show us in the twenty first century about community and artistry?

PG: Uh, my work, it's. You could think of it and understanding it. And today's, definition. Right? It could be looked as a, uh, social practice, community based work. It's another definition, but community work, meaning that we are all participate and come together collectively to support this process with our own tradition and culture as an independent. for instance, anneal or indigo is grown in an ethnic in the isthmus region of Oaxaca community. They're specialized in growing and processing Indigo other families specializes on the spinning, for instance, maybe other families, and focuses on growing some cochineal insect. Each one brings their specialty to, uh, make my work possible. We're also all dependent on each other for preservation, for economic support, and for moving things forward. And even though we are part of economics, global economic system, we still do believe that money will come as a result of what you're doing. And as long as you're doing something with great respect, understanding that this material is It's actually not produced by you. It comes from a much more greater US gifts through Mother Nature, through the greater being. And so there has to be a respect and understood there in order to get to, uh, to get to the result, which is, you know, the monetary that is needed. it's really also understanding in, in my case, personally, it's really understanding to the cycle of nature and what's available for every season. My work, each of my work. If you ever seen him in any exhibition, uh, on the, On the label of the work, often you'll see the season imprint. Meaning when and where the these the the the artist material was harvested. Because each cycle it's going to communicate color very differently than one season to the next and so on. And that is something that in today's society, it is having a hard time to cope with because these fastness and, you know, instant gratification is priority.

HL: I want to ask a couple more questions here to see if we can pull things full circle with your practice to some extent here, and to go backwards before looking forwards. You speak of being from a millinery tradition, and we've established this idea of a centuries long tradition in Zapotec cultures and throughout Oaxaca and beyond. Where does that start for you when you're growing up? When is it that you start being exposed to these ideas and other creative people and thinking of this as a creative practice. How does that happen?

PG: Wow, Hugh, you know, these are some of the things that I often think about that, I was just talking to my parents about this. My parents still live in, in Teotitlan, in, in Oaxaca. I was just talking to my folks, and, and I tried to process this information myself and think about it. And I would like to take it back a little bit. Hopefully I don't get too, too much of off site from, from, from your question is that historically when when a baby is born, uh, and even before the, the, during the pregnancy, the there's a lot of, expectation of, of maybe the responsibility of the baby and not so much on the if it's a on the gender of the baby, there's offerings, there's prayers. And once the baby is born, that in itself is a ceremony. Then the baby is then taken to a spiritual leader to understand so that so the spiritual leader can help their parents to, to guide, uh, to understand their responsibility of the baby and to guide the baby to fulfill his or her responsibility. I do think that as creative person, it does not belong to me. You know, this this thing that I that comes through me, it's not it doesn't belong to me. And I cannot take credit for it. It's in in my DNA. I, I also come from a family of musicians of, as well as, uh, as what? My parents says it in our language That we come from a family of Veneto. Veneto. It's someone that a well respected and someone that has has contributed to the community. And so, that's and they, they make sure and communicate who our families were because many of them. I didn't see them. Right. that there was a lot of creative, uh, way of, of living. Right. And that they respect and they honor the that, that, that work that they were doing. And so I think of myself in so many ways is, is, Is the seed that was planted in them and maybe millennia, right. It's sprouting. And it's sprouting here now. Today, the land that it's known, that land that it has always flourished for all these thousands of years. Seed after seed, season after season. And so, it is so complicated for me to communicate what it is because it is beyond me. It is beyond. And it is something that comes. It is something that, covers me. It is the it's these ideas that comes and it just comes out of the blue, you know, like, I don't I don't make these ideas. It comes from a greater place. And as, as a, a godly or how to say this, uh, someone with faith in Christianity, I believe, I believe it comes from God, from that greater being. And so throughout my prayers, it is this interaction of ancestors, traditional knowledge, my beliefs, spiritual beliefs today. And I really try to just to be in that space. That is really my understanding of, of of creative. Uh, there was when I think about myself, when I think about, Western education, I've only gone to sixth grade. You in, in Western education, you know, and, and, and when I look back and different experiences and the work that I'm doing today, uh, it just it's hard for me to comprehend other than just me being extremely grateful for it.

HL: It's it's incredible that you you mentioned that and kind of connecting with what we might call an ancient seed and how that is planted and sprouting today to to bring that idea of the ancient seed that it's perhaps sprouting today and pull things full circle here with the final question that during Covid in Southern California, you started a studio to pass your art and knowledge on to your sons. How are you teaching your children and other local youth about dyeing and weaving? And what does that intergenerational transmission of knowledge look like?

PG: Yes. but but I want to say, beyond weaving and dyeing, what I'm hoping and what's my interest to teach is that possibility. Is that? Yeah, it could actually be done. You know, we we actually belong to this land, as many of thousands of of our relatives that has existed here for thousands of years. Today we're in the I am in the Chumash land. The relatives of the of of our relatives, the Chumash people. So, it's really to providing an understanding that that creates such of ill and, and, uh, such of mental block for so many of us that has migrated and that that are Native Americans that has migrated to today known as United States. Right. Is to actually understand that. Wait a minute. We're home with not disrespect and with specifically acknowledging which land we are in. But as a Native American, we are home. And also, I'm hoping that I'm teaching that there's a possibility, you know, beyond the, uh, political, uh, political issues and beyond the borders that, there is definitely a possibility that we could we could actually, fulfill that responsibility that we as native have for our community. That is really what if I think if I could inspire or teach, teach my kids especially. Right. It's that it is. I actually in fact, I don't particularly, uh, trying to doctrine them about the weaving and the dying. They participate as I did when I was young. But the most important thing is for them to understand us this complexity of who we are and where we live and how we exist within these environment, and how to hopefully, uh, project from there. And if that's and if that's a, uh, inspiration for, for youth and, and the over two hundred thousand zapotecs that are living LA and the suburbs. Well, that's just amazing. And that's really what I'm what my hope is, to, that that I could if I could be in any way as a reference, then it's great.

Hugh Leeman: Porfirio Gutierrez it's an inspiration. Thank you so much for doing what you do and sharing with me, I appreciate you.

Porfirio Gutierrez: Thank you Hugh appreciate it for having me.