Peter Coyote

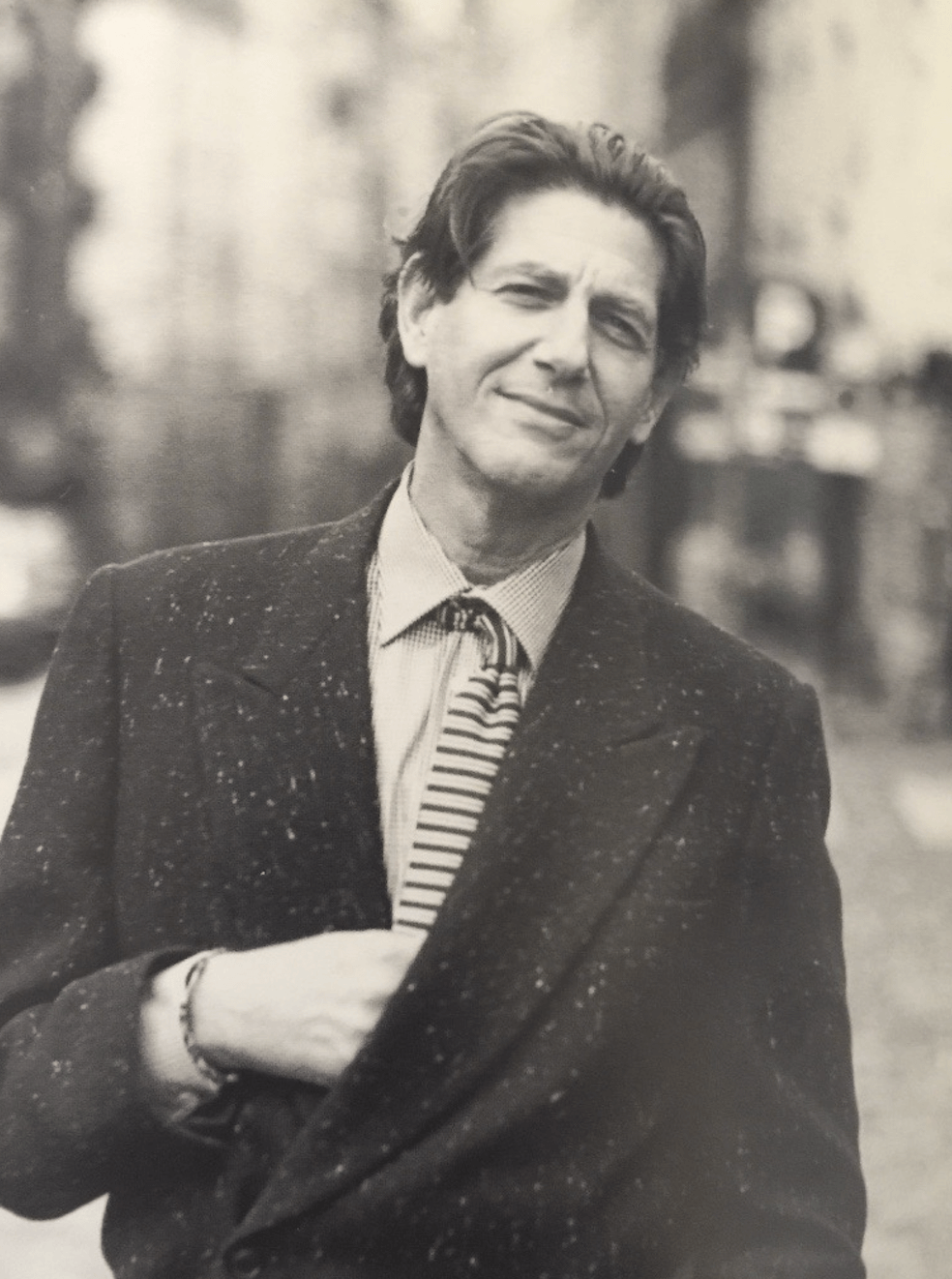

Peter Coyote has performed as an actor in over 160 films for theaters and TV. His work includes some of the world’s most distinguished filmmakers, including Barry Levinson, Roman Polanski, Pedro Almodovar, Steven Spielberg, Martin Ritt, Steven Soderbergh, Sidney Pollack, and Jean Paul Rappeneau. He is a double Emmy Award-winning narrator of over 150 documentary films, including Ken Burns ' National Parks, Prohibition, The West, The Dust Bowl, and The Roosevelts, for which he received his second Emmy in 2015. Most recently, Peter has also completed The American Revolution with Mr. Burns.

Mr. Coyote’s memoir of the 1960’s counter-culture, Sleeping Where I Fall, received universally excellent reviews and has been in continuous print since 1999. His second book, The Rainman’s Third Cure: An Irregular Education, about mentors and the search for wisdom, was nominated as one of the top five non-fiction books published in California in 2015. He has published three other books since then, including Zen in the Vernacular, a guide to Zen practice for secular people.

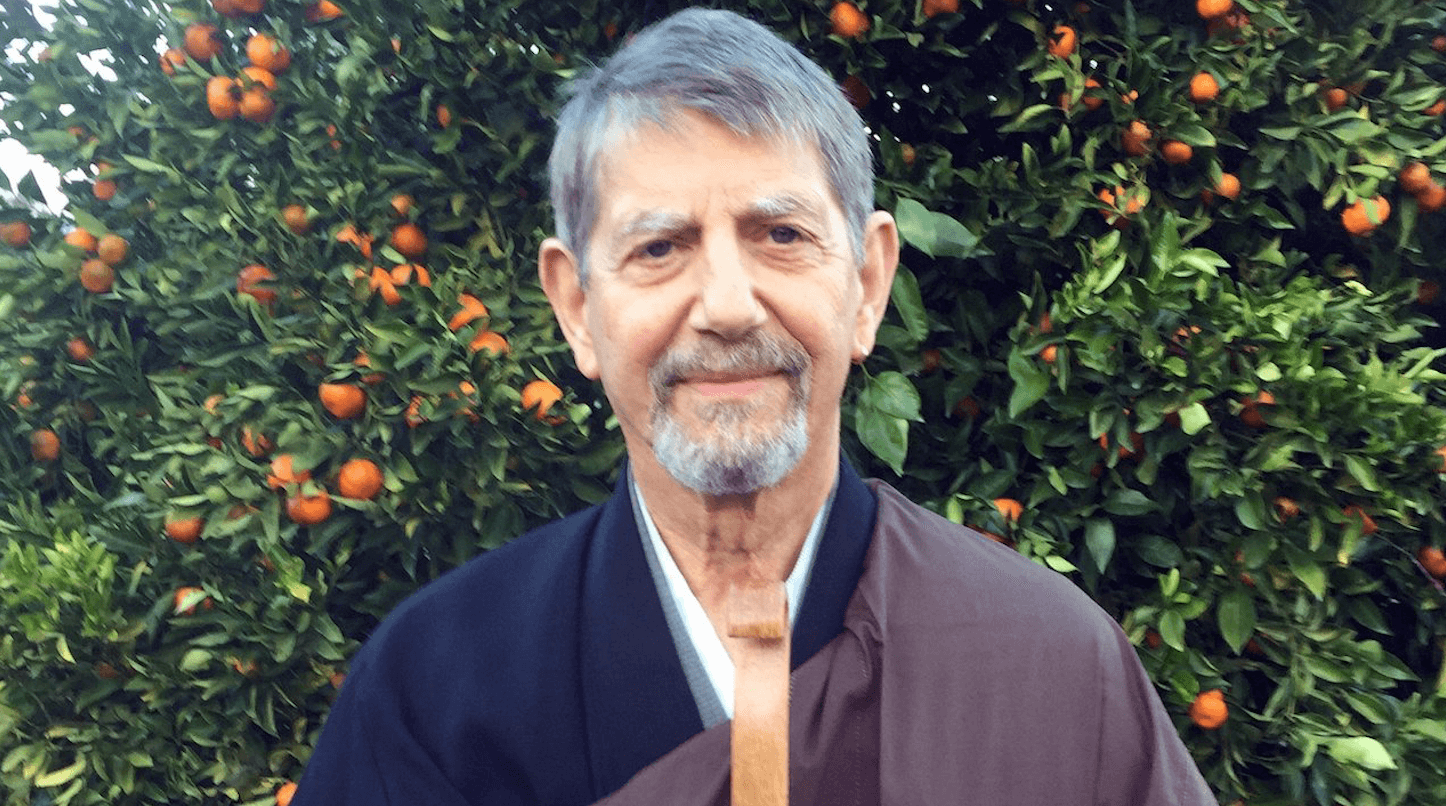

He began his Zen practice in 1974 at San Francisco Zen Center and took first vows (jukai) shortly thereafter, receiving the Buddhist name Hosho Jishi—Dharma Voice, Compassion Warrior. In 2012, he was ordained a priest by his teacher Chikudo Lewis Richmond, a former assistant to Sunryu Suzuki Roshi, who founded the San Francisco Zen Center. In 2016, he was transmitted (given independence and the right to ordain priests and transmit others) by his teacher and took four years without teaching, beginning in the pandemic of 2020. He has since transmitted two senior disciples to succeed him and carry on the lineage.

The Following are are excerpts from Peter Coyote’s interview.

Early Life

Hugh Leeman: Peter, your grandparents immigrated to New York City where you grew up in no small part raised by your housekeeper Susie Nelson. Who was Susie Nelson to you and how did she influence your childhood?

Peter Coyote: Oh, wait. So, I'm going to get you a picture I just got today. Okay. Of Susie. Just a minute. So, I have this little snapshot which I got blown up and just got back today. So, this is Susie and Ozzie Nelson getting married at my house. .

So when I was about two and a half years old, my mother had a crippling nervous breakdown. Turned her into an eggplant. And my dad was too busy minting money. He was a real type A personality. He was kind of afflicted with the fact that up until the 1960s, Jews were not considered white people. And he had a real chip on his shoulder about running into prejudice. This is a guy who went to MIT when he was 15. He was the sparring partner with Philadelphia Jack O'Brien, who was a world light heavyweight champion. His black belt in judo. He was the president of an oil company, president of a railroad. He had his own stock brokerage house and he and a partner in Texas brought these magnificent French cattle called Charlay cattle into the United States. He made a huge empire. But, you know, he was a great man. He wasn't a great father. And I think he was afraid maybe that I—I don't know, maybe he thought I was gay or I was just a tender, poetic little kid.

But anyway, when my mom had this nervous breakdown, my aunt sent 17-year-old Susie Howard, her name was, to come in to work with my family. And she was an amazing person from Henderson, North Carolina. Her grandmother was about 4 foot 8 inches tall, inky black, jet black. And back in those days, she was making a dollar a day in the cotton fields, which was twice what a man was making because she could keep three tobacco bundlers busy hanging tobacco over poles and bringing it into the drying houses. So Sue comes from a long line of amazing women and she had a grandfather that might have been a Cherokee Indian and one of the family biographers tells me he might have been a white man who found it more convenient to pass as an Indian being in love with a black woman.

Anyway, Susie came up and she met my family and my dad was ready to hire her right away. And she had been—when her father was making a dollar a week in Henderson working in the croker sacks, the bag companies, you know, the hemp—I forget what they're made out of now, but she was making $13 a week babysitting for white children. So, she left the South when she was 16 and she was in an art store. She came up to Patterson, New Jersey to live with an aunt. And one day my aunt, my father's sister Ruth, who was a painter of linoleum—she would make patterns for linoleum production—she was in an art store looking at stuff and Sue came in with her aunt and kind of an obstreperous looking 11-year-old who was acting out and the mother kept yelling at her and yelling at her and finally Sue turned around and said to the aunt, "Listen, if you want that child to behave, you got to model the behavior you want. You can't just be yelling and screaming at him. You got to show him what being right is."

And my grandmother was blown away from this. And you can't imagine this today, but she walked up and she put her hands on her shoulders and said, "Do you have a job?" And Sue said, "No, but I'm looking for one." Because she'd just been fired from the army. She'd been making coats. She was underage. And they found out that she was underage. They fired her. So, she went to become my aunt's housekeeper. And the two women became very, very close. And when my mom became helpless, she sent Susie Howard into our house.

And Susie was like a woman that had survived a lightning strike. I don't know what it was. She was fearless. When my dad said, "You got the job," she said, "Just a minute. I left the South because I wasn't treated with respect and I'm not going to work for you if I'm not respected." And he just laughed. And my father was a man who was beating grown men so badly they sued him for assault when I was 18 and 19. He was a truly dangerous man. Pull you out of your car, beat you so badly a bus pulls up and stops and all the people jump out to protect the poor bastard who's getting beaten. And my dad grabs a tire iron out of the trunk and chases them all back so he can go back to beating this guy. He was afraid of Susie. He was. And he also respected her. He knew who she was. He sent her to school. He paid for her education.

And from the time until I was about 14 or 15, she ran the household. My mom took a long, long time to come out of this, and she would be sitting in the living room with a glass of scotch playing solitaire at 2:00 in the afternoon and Susie and her friends John and Violet Ellerby and Jules Monk and Chris Hicks—all these black people would be in the kitchen playing jazz, talking, Susie's working, arguing about the Bible, stealing each other's food—and these were the people that actually listened to me and taught me how to sing and taught me how to dance and taught me about whiteness and taught me about all the real important things to know about in life.

And there's just no way I can describe her. And we stayed—I buried her when she was 92. I buried her son who I always treated as my half-brother when he was about 65 two years ago. And I, when as a kid, I mean, I just wanted to be a black kid like them. And when my mom would get better, she would say every once in a while, "Darling, you sound just like a little black boy." And that was the greatest thing she could say to me, best thing she could do. And I still have trouble when I get around in black communities. My voice drops to a pitch. The cadence of my speech is a little different. It's just like these were the people that I idolized and got safety from and love from and nurture from.

And I didn't really get that from my white parents. And I didn't get close to my mom until I was about 35. And I was angry at her because my father used to just torment me and humiliate me and beat the shit out of me under the guise of teaching me to fight, teaching me how to be tough. But he was really teaching me that I could never beat him. I could never stand up to him. And I didn't understand that my poor mother was drowning. She couldn't save herself. And by the time I got to be 35 and he had died below broke, she had lost everything. Three homes. Had no idea till people were jerking her over the coffin saying, "Ruthie, we want our money." She wound up in a little house on the wrong side of the tracks doing the New York Times crossword and ink, and nobody realized she had been the executive in a rich man's home, a cultured woman who sent herself to Colombia, had sophisticated friends and family members that were communists and socialists and Bohemians.

She was a great lady, but you know, it would be like being married to Donald Trump, except my dad didn't fuck like that. But he had that same sense of power and nobody's boundaries mattered at all. So she to me was like an emblem of a kind of courage. And her husband Azie, Azie Nelson, he was the gentlest, funniest man I ever knew. He was a gospel singer and he worked in a lathe factory in a fountain pen factory working a lathe. But he did like a cappella gospel like the Swan Silvertones. And to this day, I listen to gospel on Sundays. So these people made—I don't know if much if not more impression on me than my white parents because I left home at 18 and I never came back. Soon as I went to college, I was gone.

Hugh Leeman: Well, there's this cross-cultural influence that you're referring to here that I hadn't even thought of from say a perspective of belief and faith that you grew up in a Jewish home, but then you just said, you know, to today I'm still listening to gospels. How did this cross-cultural upbringing affect your path in life?

Peter Coyote: Well, I'm not exactly sure how to answer that. On one hand, I can say it showed me the difference between the chicken shit and the chicken salad. I suddenly understood that all the stuff that made white people look so slick and so polished and so capable and so on top of everything was because they had black people on a leash.

And whether it was overt or whether—like my mother—Susie once told me that my dad did not have a racist bone in his body. He hated everyone equally. And my mother was the secretary of the Urban League eventually, which was an early civil rights organization. So, you know, there was a lot of affinity between Jews and black people in the 40s and 50s until Jews got allowed to be white people in the 60s.

So, one of the ways it affected me was I understood that white people didn't understand the privileges they had. Like when there was a woman in the neighborhood, Mrs. Jones, who Susie would always call Mrs. Jones, but she worked for the family of a little girlfriend of mine who could call her by her first name and never think about it. All right. So, here was a grown woman who was calling Mrs. Jones, Mrs. Jones, and here's a 10-year-old girl calling her Nelly. So, and I would see that I would go to the store with my biological mother and people would be fawning all over us and doing this and that and I'd go with Sue and they'd be following us like we were shoplifters.

So, that was one thing. The other thing was I grew up—I mean I came to consciousness at the time of the McCarthy period. So, I was born in 1941. By the early 50s, I was 12 and 13, and I was watching—my mother had a cousin who was the first communist fired from the New York City school system for being a communist. 28 years later, he sued them and got 28 years back pay. Most of these people were social organizers, union guys, teachers. There were people who'd been interested in communism, you know, in the 20s and 30s, which was a legitimate, constitutionally protected philosophy. And then the McCarthy period came after World War II when our government realized we were going to be in competition with the Soviets. And instead of really trying to teach the people, they just made communism and socialism evil. And it's still afflicted that way. All they have to do is call you socialist, call you a communist, call you a left-wing lunatic, and all discussion stops.

So, I grew up with this deep cynicism. I'm not sure that I ever saluted the flag for lying about my family, saying they were traitors and they were spies and they were this and that, or for hanging black people from trees while they're all eating sandwiches and waving at the camera. So there was something conflated about being caring about other people, being Jewish and not being white and being in love with black people that made me a kind of permanent outsider.

The Transformation: From Robert Peter Cohan to Peter Coyote

Hugh Leeman: This is a very foundational part of your life that's clearly had a major impact. There's a transformative part of your life that takes place a handful of years later. So you were born Robert Peter Cohan, and after a life-altering experience with peyote, it leads you to change your name to Peter Coyote and a transformative paradigm shift. That shift was not overnight. What was the journey like that led to this transformative identity shift in your life?

Peter Coyote: So I mean I posited you this feeling of being displaced from the majority culture. I mean, I'm not beginning to equate my suffering to the suffering of black people, but I couldn't go into the country club a block from my house and go swimming. So, when my friends and I were all playing and it got hot and they all said, "Let's go swimming," and I'd say, "I can't go swimming. Let's do something else," they'd say, "We'll see you tomorrow." And they'd run away and go swimming. So, it reinforced this sense of being an outsider.

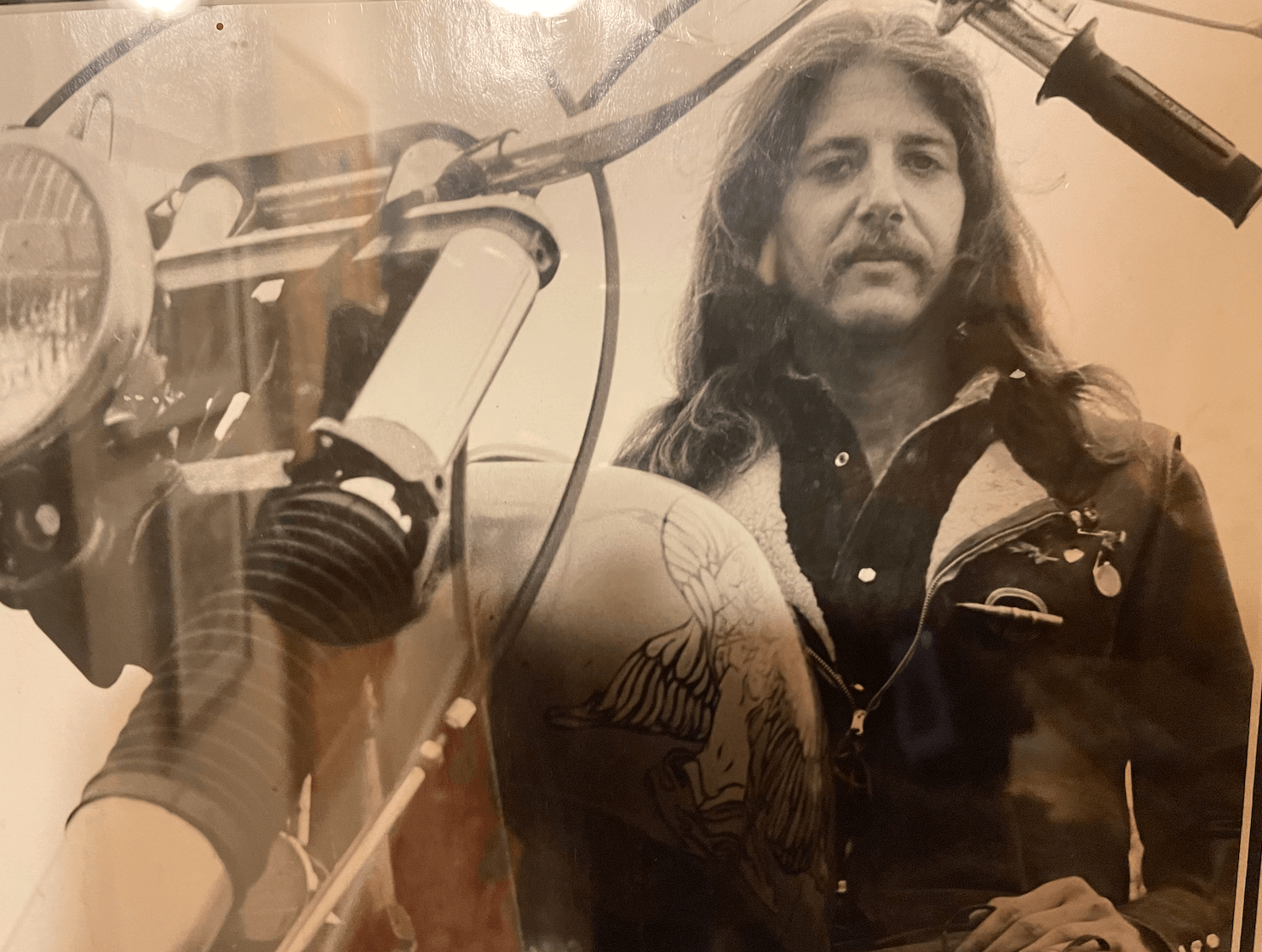

So I went to my—when I was about 13, I got really interested in cars and hot rods and building things and I like the logic. I have ADD and you know just kind of my mind is like fireworks going off all the time. So when I was about 14 I got really deep. I bought a motorcycle in a basket, an English motorcycle, an AJS, and it took me a year and a half to send to England for the shop manual and get the parts I needed and put it together out in a shed in our garage. And I got it running and 14 years old, I was tearing around my neighborhood. And then one day I pulled in the house just behind my father's chauffeur with my father in it coming home early and he saw it and he said, "Is that what you've been doing out there?" The next day the motorcycle disappeared.

So they worried I was hanging out at the garage and working in the Sinclair station. So they took me to Martha's Vineyard for a summer. They left me off farm chores and we went to Martha's Vineyard when I was about 15 the first time and it was fantastic. I met kids from Harvard and Boston and New York and intellectual kids who were reading the books I was reading who were way ahead of me in terms of folk music and they were really sophisticated. And for the first time I kind of met like a peer group. I wasn't weird. The things I was interested in were what they were interested in. And these were cool kids. A lot of them were rich. One of them gave me his Porsche to drive around for a summer. A little Porsche Speedster. Another guy, my sister was a gorgeous girl. And she was like, I don't know. She was like a lioness in Martha's Vineyard. All the guys wanted to get next to her. So this guy Peter Point Johnson gave me his aerial square four motorcycle to ride for the summer and Tom Rush would come over and I'd make him teach me licks on the guitar if he wanted me to disappear to court my sister.

So seeing these kids and seeing the respect they had for learning and that curiosity was respected and that we were listening to the same music and it was blues and gospel and Appalachian music and it just kind of opened me up.

So then there was a funny little period. I traveled cross country one summer with a friend and we stopped in Mexico to see a friend of my family, a brilliant guy named David Campbell. First overtly gay man I had ever met. I mean, he was just out there. He was living in the hotel Teresa. His roommate was Billy Holiday. He was passing himself off as a black man and he came from the Campbell family in Hawaii, a very wealthy banking family. He was turned out by a convict in his garage who was working at the house and he was gone and a concert pianist. He was a dancer with Martha Graham's company and he was a family friend. And so when I told my family I was going to go to Mexico, they were a little nervous. I said, "Oh no, I'll stop and see David Campbell. It'll be okay." I don't know what they were thinking, but they said, "Oh, fine."

So, I went to Mexico and in Mexico I got turned on to weed by David and we drove through the out to bumfuck Egypt somewhere at dusk and for $60 we bought eight kilos of weed. I mean it was a huge bushel basket and I mean there was nothing better. So for about a month we were tripping through Mexico, being high, going in the bars, drinking tequila, chasing chicks, doing whatever we could do. And finally, I realized that I was going to bring this back to the United States because my parents were like alcoholics. I'd had friends killed in car crashes going upstate New York to drink and driving back loaded. So, I loaded this shit in the car and we spent two days in a motel room with towels around the doors and stripping the leaves and packing them into little tight bricks. And all you had to do was look at the outside of the windows where there's about 10,000 narcotized flies hanging on the screen door completely loaded.

Anyway, I got busted at the border and me and my friend were thrown into jail and I did 10 days in jail because I was more afraid of calling my dad than I was of the jail. But I finally called him and his partner was in Harlingen, Texas, not far away from where we were in Brownsville. And he was one of the hundred Texas families that ran that state, and he had a wife who owned a million acres of land in Mexico, 35 miles of beachfront. Anyway, they got me bailed. They got me paroled to go home and I had to go back to trial in December and because I was 17 then I was a juvenile delinquent and I was not given a felony.

So I got the next year I had to repeat my junior year and senior year. So, I went to college. I was older than most of the freshmen. I was almost 19. And I brought with me, I went to a school in the Midwest called Grinnell—it's a really high quality small liberal arts school, kind of a training ground for the state department, like Oberlin, like Haverford, like Swarthmore, one of those schools. And no fraternities. And 98% of the faculty were PhDs and I was just like a pig in heaven. I mean really smart people. I met my—well I'm the last of my friends from college that's still living. But we made a—the year that I came in they had made an allowance and they increased the number of kids coming from the east coast by 10%. So there were all these sophisticated kids that came from the east coast and we introduced the school to like folk music and we started a coffee house in town that made the faculty members just deliriously happy to have someplace to go.

And while we were there in 1962 the Cuban missile crisis occurred and 14 of us just got the feeling that we were not going to grow old enough to enjoy our majority. We were not going to get the chance in this world, that these adults were going to blow it up with nuclear weapons. So, we put together a group of 14 people. We raised the money. We bought two old clunker cars, a 48 Chevy and a 49 Ford. And we drove to Washington and we did a three-day fast in front of the White House and we made the above the fold in the New York Times and Kennedy saw it. He was flying to Arizona and he invited us into the White House. First time in history protesters had been invited in the White House.

And we were staying in a place called Gunk House. Perfect name for people who were fasting. And this guy comes rushing in to tell us—he was McGeorge Bundy's chief of staff who was Kennedy's—you know, Rumsfeld—he was Kennedy's national security adviser and he was telling us what this meant that this was an incredible opportunity and his name was Marcus Raskin and his son is Jamie Raskin who's still serving in Congress today and I sent Jamie the copy of the story that was published about the Grinnell 14.

So we utilized the publicity of that meeting to write to a hundred colleges and to get people to replace us week in and week out until February of 1963 when the first 25,000 student demonstration in Washington occurred. And Tom Hayden called the Grinnell 14 the founders of the student peace movement.

So that's what I was doing in college. So while I was in college, a bunch of us wrote to Moore's Orchid Farm in Texas and we got a box of peyote about three feet long. We didn't know much about it, but I knew enough about scoring dope and stuff. We went to the library and we found there was a peyote cult at the Tama Indian Reservation about 30 miles away from the school. So me and my friend Terry Bisson, we went over there and I found the guy and we made a deal and we gave him half the peyote and he told us how to take it, what to do.

So, me and Bennett Bean, who grew up to be one of the world famous ceramicist sculptures, and my roommate George Wallace and Terry Bisson and I, we all took about eight buttons of peyote. We took a massive amount of peyote and nothing seemed to be happening, man. And so, at some point, Terry said, "I'm going back to the dorm." And when he stood up, he said, "Hey, my hands are dizzy." And as soon as he said that, it was like we were all just high as kites. And we went outside. It was dark. It was a beautiful cool night. And I turned to him, I said, "Terry, this is really weird, man, but I feel like I'm some kind of little wolf or something. I don't know what it is. I got to go."

And I spent the night dog trotting around the pastures in Iowa just tripping. And when I woke up in the morning, I was standing in a field that was covered with these little footprints. It's like a coyote footprint. It's exactly what it is. And I didn't know if I'd made them or what had happened. But so I just stashed it. It was just something that happened.

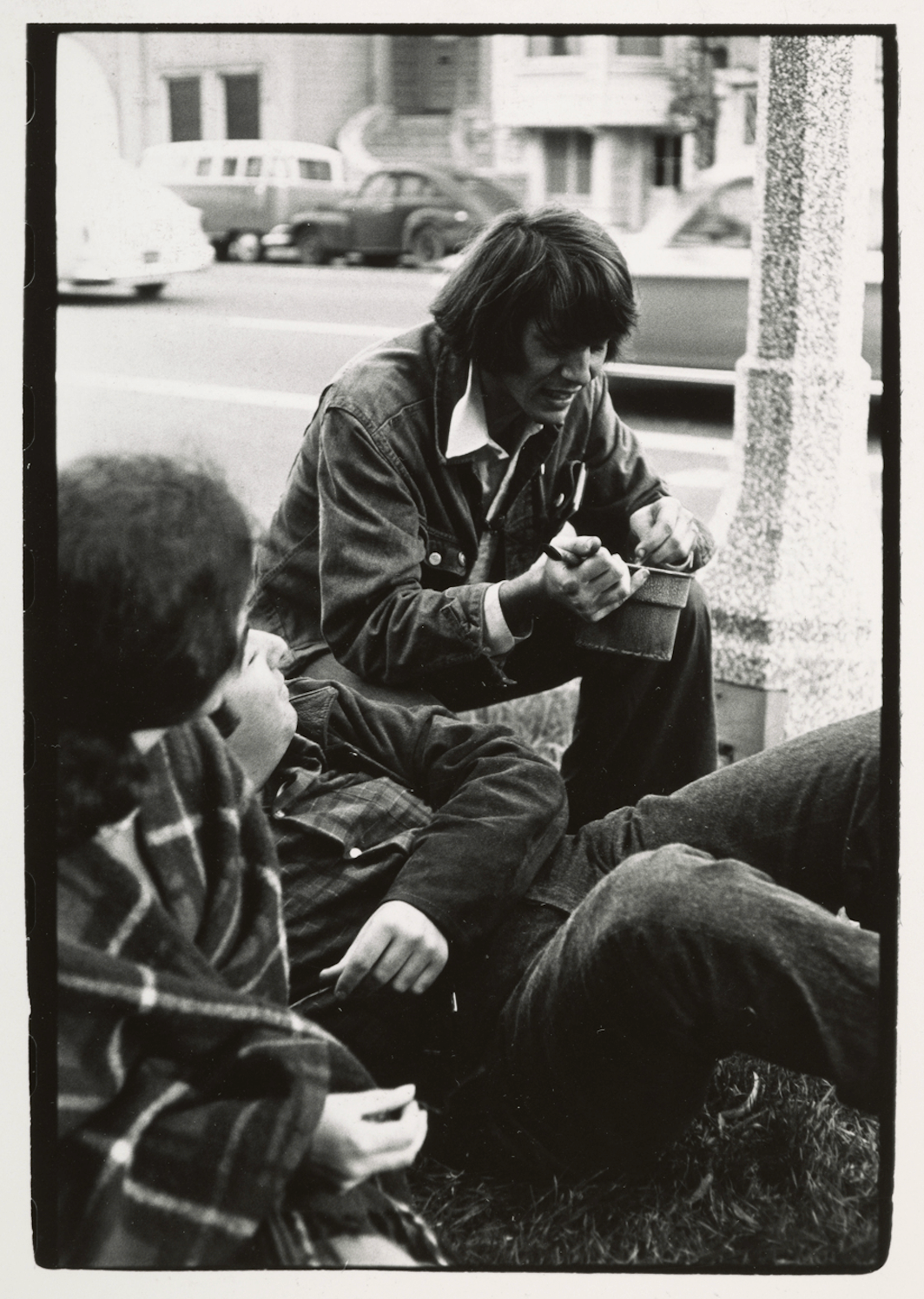

Well, about—I went out to San Francisco to go to graduate school, creative writing department, and I dropped out after about a year because the counterculture was starting to thrive. And I joined a little street theater called the San Francisco Mime Troupe, and the San Francisco Mime Troupe spawned a group called the Diggers, which was the people that most stretched the boundaries of the counterculture to try to create theatrical events that would give people the experience of living without profit or private property or invested in their ego. We're really good at it.

Anyway, while I was doing that, a guy came to San Francisco named Rolling Thunder. His name was John Pope. He was a Shoshone Paiute medicine man and he was a railroad man. And he was about half carnival barker and half the real deal. And I moved into his house for a while in Nevada. And I pulled his son out of some cult commune. And I just fixed his toilets and his cars and just hung around because I knew that the encyclopedia of Britannica of how to live on this continent was Native Americans and they had the information about how to live here in a sustainable fashion that I wanted to learn.

So one day we were having a smoke and he would share his kinnick-kinnick with me—Indian tobacco—and I told him this story about the peyote meeting and he looked at me and he said, "Well, what are you going to do about it?" And I said, "What do you mean?" He said, "Well, the universe opened its mind to you. You could treat it as a hallucination. It's okay. You'll just grow up. You'll be a white man, you'll live a normal life, nothing will happen. Or you could dedicate yourself to trying to learn what it meant, what it implied. Be a human being."

So that really sunk into my head—a human being. That's what I wanted to be. And I thought about it for about three months and I took the name as the first step to paying my respects to it and to understanding it. And then there was an immediate unintended consequence, just mind-blazing, which was nobody on earth, including myself, knew who Peter Coyote was. He had no personal history. And I would just have to watch and see where the rabbit came out of the bush to find out what was up. And it started me—it enforced a kind of improvisatory living which I had practiced in this little theater and I had grown up—one of my father's best friends was a bebop jazz musician guy named Buddy Jones who'd been Charlie Parker's roommate in Kansas City and came to New York with him and my dad loved this guy and he loved jazz musicians because he helped a bunch of them buy land near us in the Delaware Water Gap in Pennsylvania.

And this guy, Buddy Jones, was a mentor and a teacher to me. And he was a jazz man. He lived on the one. He didn't repeat anything. It's a great story. He'd been high every day since he was 17 years old. He was from Hope, Arkansas. He came from another little small town. And the first day of school, he went in there. He was a strange kid and a woman slid over on the bench and tapped it for him to sit down. That was Virginia Clinton. That's Bill Clinton's mother. And he grew up in this town and he got a job in the funeral home. And he was the only guy who would do black funerals, treat black bodies for the funerals. And he was a concert pianist. And then he went to Kansas City, met Bird, and he couldn't swing on the piano. So he became a bass player.

So he got—he came back to New York and his friends were like Al Cohn and Zoot Sims and Dave McKenna and Herbie Green and all these great guys. And to hear this music, never repeated, so expressive, always just on the one seemed to me an emblematic way to live. And that if God had been kind, he would have given me the musical IQ to be a jazz man. But what he did was he gave me the musical IQ to be a back porch finger picker. Four chords, you know, that's my IQ.

So Buddy Jones was in the Navy band and he was on stage and he was smoking his pipe full of marijuana. They were waiting for Harry Truman to come in and he'd lit the pipe and he was standing there with it in his teeth and suddenly the band leader strikes up Hail to the Chief and he's got to play. He's got the pipe in his mouth and he's going, he's getting high, he's playing and the president comes in and afterwards there's a reception with Haile Selassie and they're all going down a handshaking line and so this is pure Buddy. Buddy goes down the line and puts his hand out and Haile Selassie says "Haile Selassie." Buddy said "Highly delighted." I mean that's who he was man. That's how he lived. I'd be 10 years old. He'd come into the kitchen in his coveralls, smoking a pipe high, and he'd be singing, "Nothing could be finer than to be in your vagina in the morning. Nothing could be sweeter than you eating on my Peter in the morning." I'm 10 years old. Who is this person? And he and David Campbell were friends. So when I say that my parents said, "Okay, you can go with David Campbell," you can see why I was a little surprised.

Anyway, I've lost my thread here.

Hugh Leeman: Well, you've mentioned some very interesting—Cuban Missile Crisis, your activism. You also mentioned then this incredible transformation with the peyote and you mentioned something very interesting. I think it would be wonderful to have you give some context on the diggers and the mime troupe. Who were the diggers and what inspired their free food giveaways every day in Golden Gate Park?

The Diggers and the Mime Troupe

Peter Coyote: Okay, so let's start with the Mime Troupe. Which was an Italian 16th century commedia theater with stock characters with masks—Pantaloney, Dottore—and we rewrote these plays to talk about contemporary political issues. And we were extremely left-wing but extremely funny, extremely improvisatory. And we went to the parks where the people were. And we made a living by passing the hat. We were quite famous. There were other groups like Peter Schumann's Bread and Puppet Theater in New York, but I don't think any of them were as wacky as the Mime Troupe was. And we were all dedicated kind of leftists.

And then one day, two guys came out from New York—Emmett Grogan, who was a very charismatic Irishman, a real Irish rogue, handsome, smart, very tough. And with him was a quiet, mousy little guy named Billy Murcott, who was the brains of this thing. And they challenged us. They said, "Listen, man, you guys could do more. We understand that you're improvisatory, that you can work without the script, but you own the stage. You know the form. If a drunk gets up, you can do a little routine with the drunk and then you dance him off the stage. You go back to the play. We want to start pulling people into plays that are going to change their lives."

So this is pretty fascinating. What did we mean? So our analysis was that the basis of American culture was profit and private property. So, we thought that if you did things for free and you did it anonymously—in other words, you weren't trying to get rich or famous—that was a pretty good test to your sincerity.

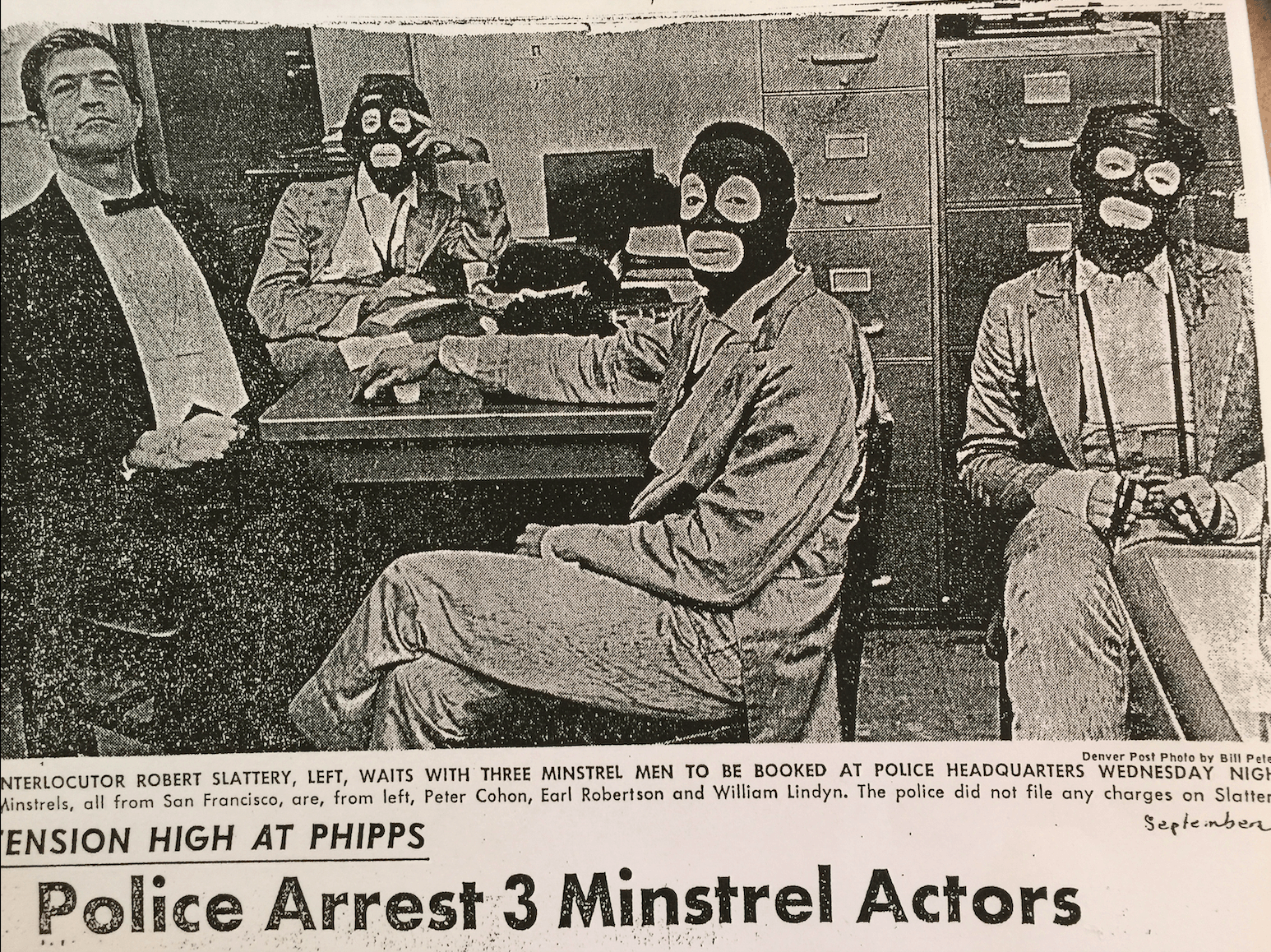

Now, one of the shows that the Mime Troupe did was we did a show called the Minstrel Show, which is the most dangerous piece of theater I was ever in. It was three black guys and three white guys in blackface makeup with natural wigs and sky blue tuxedos and white gloves. And there was a Marlboro man, handsome white interlocutor in a tuxedo. And it started with us cakewalking and tambourining into the room and singing, you know, "Something took place by the great colored race way down in Georgia." And then they do these old shit jokes like "Bones, are you a Republican or a Democrat?" "Well, that was a Baptist." And we did that for about 10 minutes. And then the minstrels tied up the interlocutor. And then we put on something called Neo History Week where we started telling black history from perspective of Malcolm X in comic routines.

And we took that all across the country. Harry Belafonte and Nipsey Russell came to see it in our studio and they were so knocked out they called Dick Gregory who was like a great moral figure, a comedian and he invited us to New York. So traveling by doing shows to get to New York, we were arrested at least six times. We were arrested in Canada. We were hired by schools that were expecting a racist minstrel show. And the first time the shit hit the audience, they'd cut the lights out or they'd throw shoes. I mean, I was on trial for 10 days in Des Moines, Iowa. We had been at the end of a show in a big 1200 seat theater in Des Moines. I saw the police and the dogs backstage and I announced to the audience that the police were back there, but we were not going to be arrested backstage. So, we climbed into the audience and they had to come in. Well, they caught three of us, but you know that meant three six foot 4 inch guys in fright wigs and blue tuxedos got away. I was just looking for my phone because I can show you a picture of it. I'll send you a picture of me and two guys in the police station with the interlocutor.

Anyway, so I mean I tell you that to say that the Mime Troupe pushed theater about as far as you could go and then Emmett and Billy Murcott pushed us farther. So the first thing we did was—the Haight-Ashbury was attracting a lot of publicity, was being written up in all the newspapers. Kids were running away and coming to San Francisco. They were running tour buses down the street looking at us like orangutans. And we were like spray painting the windows shut or spray painting the lenses of their cameras, you know, "Fuck you. Look someplace else." And the city was making a lot of money off it and a lot of publicity, but they weren't doing anything for the kids who were homeless, who were foodless. So we said, "Let's feed them."

So we first tried going to the farmers market, but the Italians would not give any food to men. They just wouldn't. Young strapping young men for nothing. So we sent the women with babies in their arms. They gave them tons of food, which we cooked up in big stews on milk cans, big 25 gallon milk cans. And we advertised free food in Golden Gate Park, 5:00. Bring a bowl and a spoon. That's all you need to do. And we erected a 6 foot by six foot rectangle painted bright yellow. And we called it the free frame of reference. And all you had to do to get the food was step through the free frame of reference. And when you step through, we'd give you a little one on a shoelace and just invite you to look at the world from a free frame of reference.

So people would—some guy would come up to me and say, "Well, I can afford to pay for the food." And I said to him, "Yeah, but wouldn't you like to live in a world with free food?"

So the next thing we did was we started a free store. And at first it was just a collection of junk. But within a year, we had a really elegant storefront and we had all these goods that people had given us and we'd repaired. TVs, radios, furniture, bicycles, clothing, everything you could think of. And it was in this perfect store, just looked like a store. So, somebody would come in and say, "Well, who's in charge here?" And we'd answer, "You are." And if they just looked stupid or their jaw dropped or something, there's no sense blaming the pigs or the man for your difficulties. You just got offered total freedom and you dropped it. But if you stepped up and said, "Really? Well, I hate the way these shirts are being presented," we'd go with you and we'd change it the way you wanted.

So people understood the exchange economy almost intuitively. One day I was in charge and there was an elderly black lady who was stealing stuff and looking around very furtively and like stealing shit. So I went up to her. I said, "Ma'am, you can't steal here." She said, "How dare you? I'm not stealing." I said, "I know you're not stealing because it's a free store, but you think you're stealing. If you want something, just take it." She said, "Just take it?" I said, "Yeah, it's a free store. You see the sign?" She said, "It's free?" I said, "Yeah." She said, "Well, then get out of my face." I said, "Okay." The next day, she came back with a flat of day old donuts and left them on the counter.

So, we took that one out pretty far, too. San Francisco was a shipping ground for Vietnam and we got a whole bunch of federal draft card blanks and we got the codes for how to fill them out—they had like six squares on them, little rectangles and numbers had to go in them. And one number would tell you that it was from Albany, Georgia or it was from Marietta, Ohio. Another number would be the last two digits of the date of birth. We had it all out. And with a little—and this is a heavy federal beef if we'd gotten caught—but with a little judicious talking, Billy from Chillicothe could come in and leave his uniform with the used clothes. We always told him to keep the boots and put on somebody else's used clothes and walk out as Bobby from Marietta, Georgia. And these were kids that didn't go to Vietnam, that didn't suffer from PTSD, that didn't take innocent lives, or weren't wounded or traumatized themselves.

So, we had doctors from UC Med Center coming in on Wednesday night treating people for free. And that Haight-Ashbury Free Medical Clinic is still running. A doctor named David Smith took our thing over. And you know, 60 years later, it's still running. So our thinking was that Americans were not going to throw themselves on the barricades to be the Marxist lumpen proletariat. But if they built lives that they enjoyed, they might defend them. And so we wanted them to build lives that they enjoyed and realized like the free store—the implication of the free store is why do you want to be an employee to make the money to be a consumer? We'll give you the shit. Now, what do you want to do?

And these things we would do—I mean, we just did dozens of inventive things like setting up a table on the freeway in the gravel at rush hour with a perfectly laid table for four, orange juice, coffee, cream, croissants, and me and Ron Thelin would be sitting there two feet away from rush hour traffic and people would be looking at us and we'd say, "Join us. Get out of your car. What are you doing? Come on." We'd go down to the financial district at the end of the workday when all the stock market people getting out with a big truck with bare breasted girls dancing, conga drummers, flutes, bottles of red wine, and just say, "Come on, man. Just join the party. Get up here."

So we did that for a long time for about three years and then it—you know it was not my highest aspiration to run a soup kitchen. Other people did that. So we moved out to the country. We began setting up communes both for economics and because we loved living with each other. And we had a string of communes that ran from San Francisco to Forest Knolls to Olema where I lived up to Forks of Salmon in the upper Trinity Siskiyou wilderness. We had a fishing boat off the north coast and we just were building an alternate economy.

And then Reagan came in and they just began culling the surpluses. You couldn't go to the back of Safeway anymore and get the just ripe food they threw out. They started selling them to hog farmers. We'd have to fight those guys to get the food. So, and then the other big change was children. When children came in, you couldn't run a completely anarchic free lawless commune or culture. You couldn't have wino Eddie playing the tom-tom at 3 in the morning when mothers were getting up at 5 to nurse. So, those people that couldn't take any regulation, they had to leave.

And then as children got older and the sources of income began to dry up, the Forest Service wiped out a lot of our land claims, burned our cabins, threw us off because they didn't like that we were witnessing irresponsible logging practices and logging on too steep soils that was flooding the Salmon River with crushed granite, wiping out the salmon. So they got rid of us. So people had to go then look after their own employment or move closer to schools. And although we looked like we were civilians like everybody else working and doing this paying rent and stuff, we still have 108 diggers in a network who are given money every month to support about 15 of our people that got old and are indigent. And we're able to give them $200 a month. So, it's not like we sold out. We just adjusted and did what we had to do.

Acting and Writing Career

Hugh Leeman: It's incredible. You know, you mentioned the idea of Vietnam and to think the impact you had on some of these individuals' lives—like you say, you know, not only do they not go to the front lines and whatever could have happened, but the association with PTSD and you've clearly had this domino effect in their lives and then their children's lives the way that we know now PTSD is something that really spreads effectively. I want to turn our attention here to your acting career and your writing career. You've performed for some of the world's most renowned directors from Steven Spielberg to Steven Soderbergh and beyond just to name a couple here. You once reflected even after acting in dozens of films with great directors that quote "I think of myself as a writer who makes his living as an actor. Acting was never the source of my joy and fulfillment. One felt authentic and one didn't." End quote. What about writing feels more authentic or joyful to you than acting?

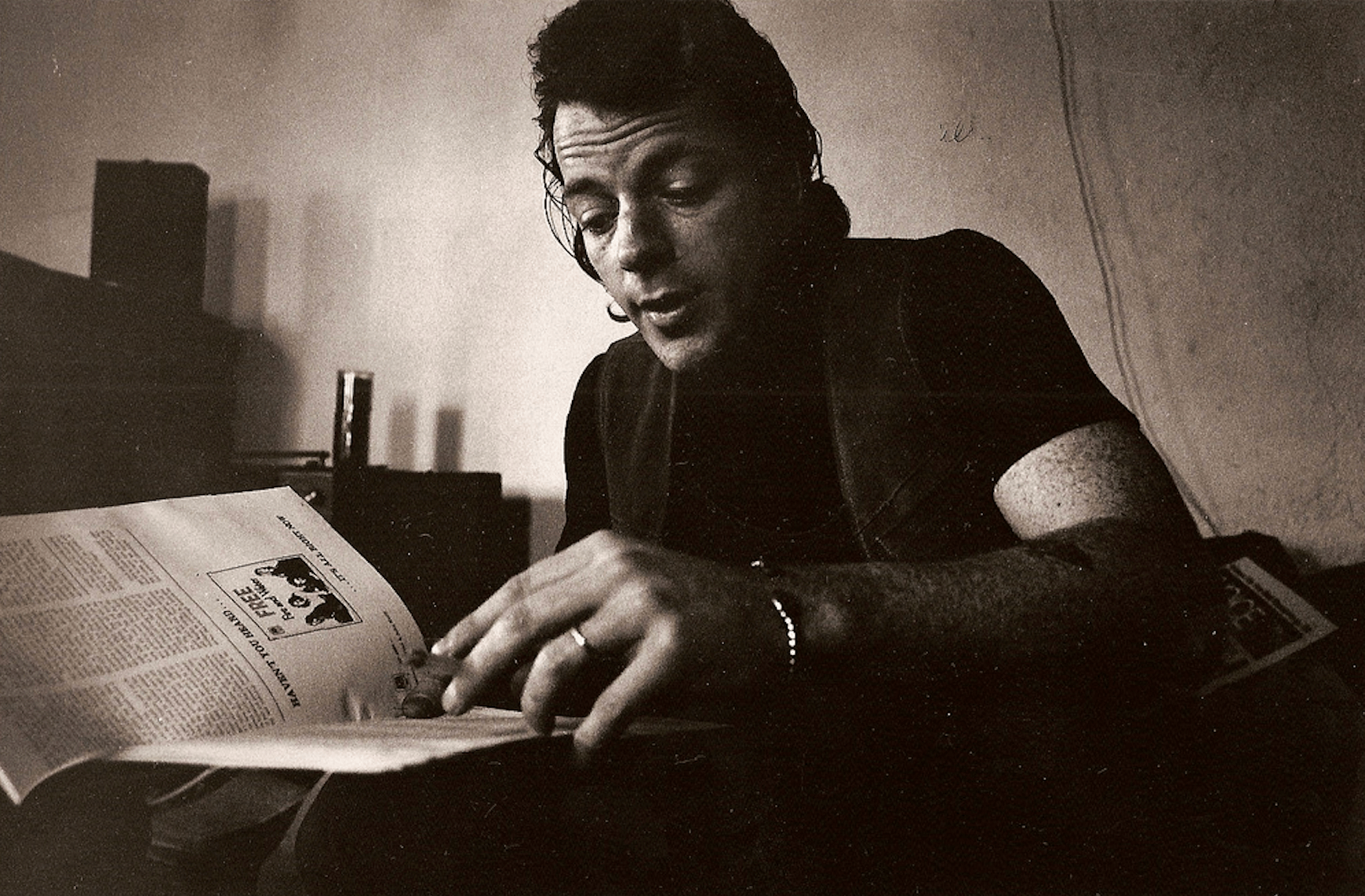

Peter Coyote: Well, it's painful for me to talk about acting. So in 1975 I was like a poverty artist, a local guy named John Kriedler took Comprehensive Education and Training Act money and created a program for artists and I was—a thousand people showed up and I think a hundred were hired and I was one of them and I was muddling along just didn't exactly know what to do. And Gary Snyder won the Pulitzer Prize and Jerry Brown appointed him to run a state arts council with working artists and Gary and I had become friends. I had read about Gary as a teenager with the Beats and figured if anybody knew about Buddhism, he knew about it. And he asked me to join—asked me to help—and I joined the arts council and it was just something I was gifted at.

After years of traveling around the country, you know, with hair down to my ass and going everywhere from rednecks to black people and Indians, I'd learned how to talk to everybody. And so the second year I was elected chairman and I was chairman for four years until the state legislature passed a bill that I couldn't do it anymore. But on my watch our budget went from like $1 million to $18 million a year and my dad had died below broke, penniless. And I had a child whose mother had run away and I was 39 years old. I didn't—I was making $600 a month as a cedar worker and I needed to have an economy.

And the success at the arts council gave me the confidence to try being a movie actor. I was 39 years old. I had already started living at a Buddhist monastery across the street practicing zazen, meditating. And I was going to go into Hollywood. I was going to go into this snake pit of egoism and ambition and striving and all this. And I just had to really think some stuff through. And if I'd been younger, I would have gone to England and I would have studied at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts and really learned my craft. And to this day, it's my great regret that I never really had training.

And because of PTSD from the trauma of being raised with my father who was an explosive and dangerous man—I once described his coming home as somebody rolling a hand grenade into the room and everybody was looking to see was the pin in it—I survived by blocking my feelings and pushing everything sort of into my brain to play every impulse forward. Well, if I act this out, what's going to happen? Because I mean, I could have been killed. He used to threaten me all the time. "I'm going to snap your fucking legs. Send you to reform school, you stupid son of a bitch." He frightened grown men.

So I didn't have access to certain kind of feelings easily. And you don't have to be smart to be an actor, but you have to be emotionally literate. And I just was—I realized at a certain point I was never going to be a great actor. I was never going to be in the top cadre, which was where I would want to be because it meant you get the best scripts and the best stuff. So, I was good enough to do 160 films, but I can barely look at them. I mean, I know the difference between chicken shit and chicken salad. I'm a much better acting teacher and I've helped a lot of people as a teacher. I just was not top rank. So really, I left a trail of mediocrity behind me as an actor. There's a couple things I'm proud of, but I got my kids through graduate school debt-free.

But I always knew I didn't want to write for money. I didn't want to be on a deadline. I didn't want editors. Writing was where I got to play jazz. Writing was where I got in touch with the kind of formless, fluid, creative energy of nature, which is human nature. So, you know, you can tell I like to talk, I like to read, and I like to tell stories. And I've just been writing and polishing my craft, you know, since I wrote the first poem when I was six years old. So, and I've been doing it ever since.

Masculinity, Buddhism, and Gary Snyder

Hugh Leeman: Peter, you mentioned the incredibly heavy hand of your father. You also mentioned Gary Snyder, who's someone that clearly had an effect on you in the idea of Buddhism, and you've since become a Buddhist priest. I want to hear some of your thoughts on this idea amidst what's oftentimes referred to as the masculinity crisis today from these different experiences you've had—say with Gary Snyder who you once said "Hey if this is what Buddhism looks like I want a piece of it" and it was something inspired by him—to what you've said about your father and other examples that are certainly in between. What does healthy masculinity look like today?

Peter Coyote: Well, I mean, Jamie Raskin, you know, I can think of—I think of figures from public life. I told you early on—the surest cure for toxic masculinity is to serve the visions of women. Women are the creative font. You know, we don't remember that the oldest religion on earth for 35,000 years, the religion that's emblazoned in all the caves of Chauvet and Lascaux, they were all worshiping the fecundity of women, creating the little Venus of Willendorf, revering breasts and hips and fecundity and drawing these animals in the womb of the earth to basically induce the earth to entreat the earth to keep this fertility going.

And it wasn't until about 5,000 BC that herdsmen began coming in from the steppes of Mongolia from Libya. Sheep herders, horsemen. Remember Pan, half horse, half man. That's a mnemonic thing to memorialize the entry of horsemen into ancient Greece—Pan was half man, half sheep. So these tribal people pushed in and these people were people who spent their whole lives fighting to preserve their herds from nature. They were warlike and the fight of man against nature also became the fight of man against man. And lots of people have talked about the collision of when these people came into Crete and came into the matriarchy. And it took about a thousand years for them to dominate the power of women and change the mythologies and the histories, but they did it.

And we're still living under that dominator reflex. And that dominator reflex is not a reflex that reveres nature, that reveres fecundity, that finds the value in a hummingbird, in softness, in tenderness, in nurture, and in growth. And I think we may be at a kind of point where the edges of it are unraveling. Certainly, nuclear weapons are such an expression of it, they could end the whole game, right? And if we want to keep the game of civilization going, we're going to have to put some restraints on toxic masculinity.

And you can see that in periods of great change, 70-some million people voted for Donald Trump, a malignant narcissistic sociopath, because they thought maybe it will be better for my money. Well, that's masculine thinking. That's single issue thinking. Women have surround thinking. I once said to my wife, I was talking to her about something and I wanted her to listen to me and I said, and she was doing three other things. And I said, "You know, you think you're doing full concentration in each of those three things, but you're not. You're splitting from one to the other to the other, and you're doing all of them not well." And she just laughed at me. She said, "Well, that's a very masculine way to look at it because women have diffuse awareness." And as soon as she said it, I understood it.

Women are taking care of the babies. They're cooking the meal. They're making the bed. They're taking care of the baby again. And they're just—their awareness is like that. And we've been able to suppress it. We've been able to frighten it by force. But we're now bearing the fruits of living in a dominator culture. And particularly for America, what we've been doing in the third world for a century and a half is now coming home to roost. And it's being done to us by the owners of capital, the oligarchs, the tech bros, all these guys who think because they've made a billion bucks, they're the smartest people on earth. You know, they're sick puppies.

So, and my dad was a perfect example of toxic masculinity. He lived by force and violence, force of his mind. He was a kind man. He was a generous man, but he also had a homicidal temper. Once when I was about 18, I was on Martha's Vineyard. I got a call. He said, "You got any money?" I said, "What do you mean?" He said, "Get $200 and come to LaGuardia. I'm under arrest here." I said, "What?" Okay. So, I got money. I flew down to LaGuardia.

So my dad had been in line to get tickets to the vineyard. There was a little flight there from LaGuardia airport to the vineyard. And there were about three people in line, him and two young guys. And just before he got up to the ticket booth, the woman closed it. She said, "It's my break." And my dad said, "Come on, there's three people left, dear. Can't you take us?" And she gave him some lip. And he gave her some lip. And these two guys in the back said something and eventually "Jew bastard" hit the air. And I didn't see these guys till I went to court with my dad. But he beat them so badly that he was arrested and they sued him for assault.

And when we went to court, here were the—my dad was 5 foot nine and these two six foot two, six foot three guys came to court. One guy had both his arms in casts on pipes. One guy had one leg and his hip in a cast and another arm in a cast. And my dad had put on a really big hat that came down over his ears and a really big coat that came down to his fingertips. And the judge looked at him standing between these two Goliaths and he laughed and he said, "You're suing him?" And he threw the case out of court. And as we left, my dad skimmed the hat into a garbage can and went, "Yeah." That's the judo and the sparring sessions with a world champ and the temper.

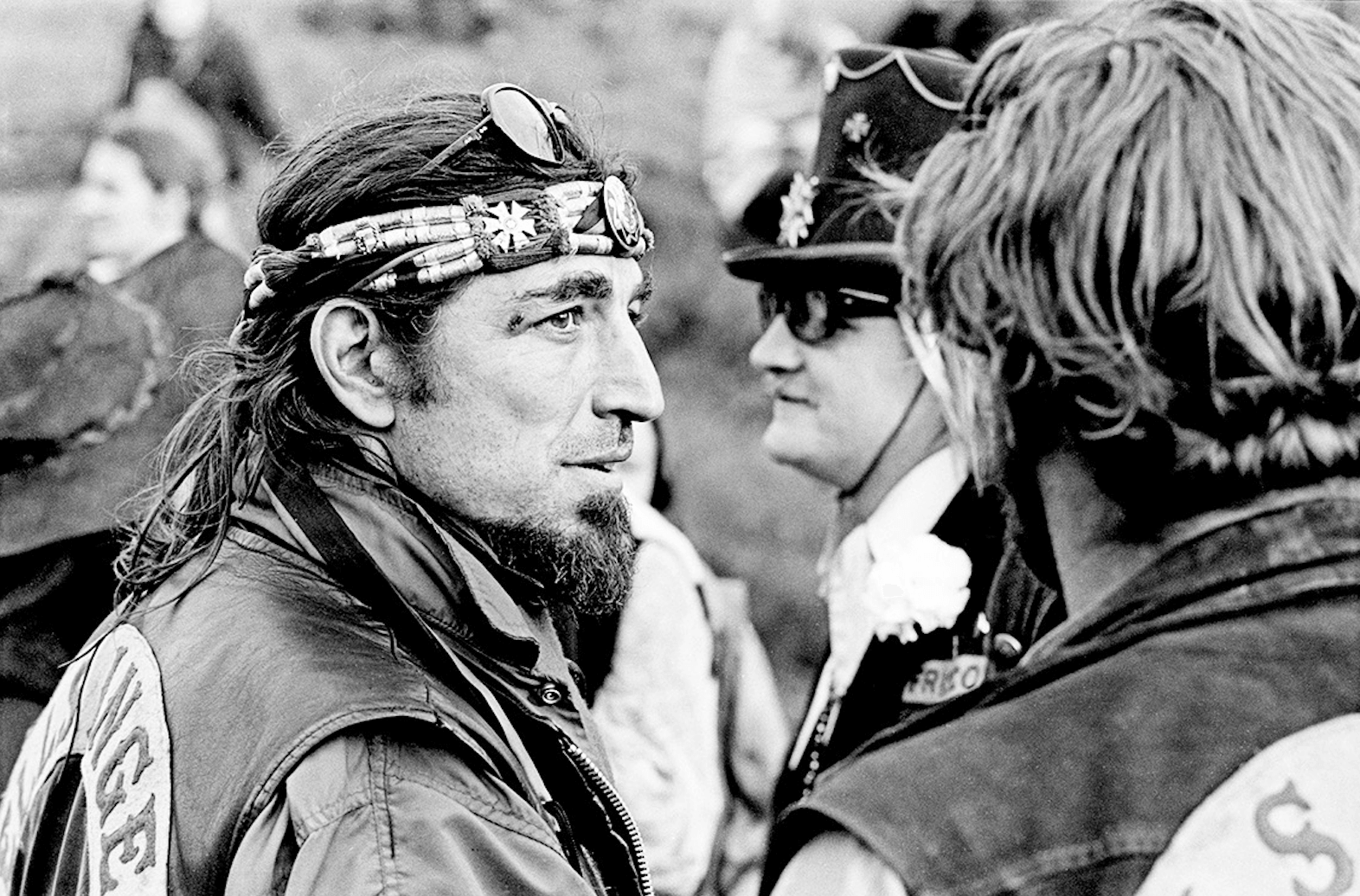

So he was a great person. I learned wonderful things about him. But he was not a good father. And he identified with me so closely. He felt that he had to mold me and do this. Had to toughen me up. And he did not see and appreciate who I actually was. I mean, I'm tough enough to have spent three years with the Hell's Angels. I'm not a pushover. But he didn't understand the artistic side of me, the poetic side of me. He just didn't get it. It frightened him on some level.

Gary Snyder was the first person I ever met who did not appear to be unevenly developed. Like my dad was unevenly developed. He had this massive IQ, this massive logical device that he could summon up in his mind. But he also was helpless before his temper and his rage and the things that frightened him. I mean, he had his own traumas. His father killed his pony with a hammer when it bit him. And his 14-year-old twin brother fell through the ice while they were ice skating and drowned. He had to go home and tell his parents. I mean, he had a lot of trauma in his life, but he never did the work to cure it. He was proud of the fact that he could fool any psychiatrist and he was rich and powerful and successful and like these tech bros, he had all the medals that culture gives you when you're important in an economically oriented culture.

But Gary Snyder did everything as well as he did anything. He fixed his jeep as carefully as he made his breakfast, as carefully as he took care of his children, as carefully as he built his house. And I just looked at that and I was amazed. I was amazed by his house. He lived in a house that was made from logs they cut down on his property. It was like a cross between a Japanese farmhouse and an Indian long house, and the amount of care and he'd spent nine years in a monastery in Japan meditating and I could see how he had thought through every detail of this thing. And I used to go up there because I was a farm kid. I knew how to do stuff. I would make myself useful to him because I wanted to know who he was.

And he was first and foremost an extraordinary scholar. And we would have conversations that would range through centuries and cultures. And one day, just out of frustration, I said to him, "Gary, how do you remember all this shit?" And he laughed. He said, "You're the first person that ever asked me." And he took me into his studio. And in his studio, there was a complete card catalog from a library, you know, 40 drawers. And in the drawers were all these little file cards. And it would say like Buddhism, Cambodian, Laos, Vietnamese, Japanese, Chinese centuries. And they were all cross-indexed with little black notebooks that ran—the totally organized mind of a thinker.

Now, I'm not like that, believe me. I'm ADD and it's like bing bing bing—like ping pongs in a—gerbils in a weasel cage. But I thought this was a guy that I need to learn from. This was a guy that I need to study and so I began to study Zen because I saw the fruits of it in him.

Documentary Work and Political Activism

Hugh Leeman: The idea of something that is very central to your life. You know, you've shared about the acting and the pain in that and you shared about the writing and you know what you've published with Mother Jones and left-leaning politics. You've been best known for voicing documentaries from the Enron scandal to National Geographic documentaries as well as Jared Diamond's Pulitzer Prize-winning book Guns, Germs, and Steel, which has influenced countless people as well as Ken Burns's documentaries and beyond. And but most recently, you narrate the documentary Demolishing Democracy, outlining Donald Trump's actions. What should people understand about the power that they have at a time that people feel so powerless in a divided and distracted society?

Peter Coyote: So, one thing that people need to realize, I wrote this little book called Smothered by Riches. You know, you can get it almost for free on Amazon. And what it is is the history of the 65-year campaign that started in 1971 when Lewis Powell published a 38-page memorandum that he sent to the United States Chamber of Commerce. And Lewis Powell was on the board of directors of Philip Morris—think Marlboro—and was later appointed to the Supreme Court by Richard Nixon. And he was livid about the civil rights movement. He said, "America's done all it can for the Negro." He was livid about the kids protesting the Vietnam War. He was livid about liberal professors teaching these kids how to see American politics and economics from a liberal perspective. He was furious about what he saw as a liberal bias in the news.

And he came up with a plan to defeat it and to nullify government's ability to regulate the corporate sector. And it was immediately pulled out of sight and funded by the wealthiest people in America. The Koch brothers, Richard Scaife, who was a Mellon, Joseph Coors, people like the DeVos family. And they dedicated hundreds of millions of dollars to making think tanks like the Heritage Foundation, the Claremont Foundation, the Manhattan Foundation, the American Enterprise Institute. They pumped hundreds of thousands of dollars into scholars to think their way to combat the regulations inhibiting the corporate sector. And they put Ronald Reagan in office. And it was Ronald Reagan who brought the message "government is the enemy." They put Newt Gingrich in office who brought the message "the Democrats are evil." Ronald Reagan's press secretary was Pat Buchanan who brought the Christian Democrats and the militias in. They brought neoliberalism as the dominant economic philosophy which said any regulation of markets is anathema to a healthy economy.

So much so that by the time Clinton became president, he turned the Democratic party into a neoliberal party. Ronald Reagan ended the fairness doctrine, which had been law since 1929 based on the principle that the airwaves belong to the people and that what traverses them should be for the public benefit. These new think tanks immediately began fighting it, saying it was inhibiting their First Amendment rights, and they cancelled it. And almost immediately you had Rush Limbaugh, single-issue radio, hate radio, evangelical Christian radio blanketing the nation. And it became okay to lie because it's just your opinion. It's just your free speech.

In the Clinton administration, he passed something called the Telecommunications Act—I'm going to get to your exact question in a minute as a background—the Telecommunications Act, which ended the limitations on how many radio stations, televisions, and newspapers a corporation could own. And in two years, we went from 50 diverse media companies to three. Our airwaves are totally owned by the corporate sector today and the political spectrum we are allowed runs from center left to the far right.

Now if you compare that to every European and Scandinavian parliament, they have communists, they have Christian Democrats, social democrats, Green Party, Health Party, Fascists. They have a full spectrum of political thinking. And yet they've all agreed on the utility of taking light, heat, power, higher education, and in many cases mass transit out of the profit-making sector. So it's like the United States joined the world in world competition of poker.

So what this has created is it's created an undernourished vocabulary in the United States. Our two-party system does not give us the spectrum to analyze political results, economic results. The corporate sector is under no compunction to allow ideas that are inimical to their values. You basically can't talk about socialism which is just capitalism with regulations. So we are falling behind. So, American people don't know that there's been a 65 year movement which has put Trump in office and it's 65 years of stacking the Supreme Court and 65 years of removing the capacity of government to regulate the corporate sector.

So, your question was what can we do? Okay. Here's what I think we can do. Trump is obviously trying to provoke a response. He's taken dumb, ill-prepared people, put them in ICE. A lot of them may be people who were insurrectionists, Proud Boys. We don't know. But we do know that they're not trained. And we do know that they're never—what's the word for de-escalating?—they're never softening confrontations. They're always producing confrontations. So, there's got to be a reason that they've been given the mandate to do that. And what I believe the mandate is is to provoke a violent response from the populace so that he can declare martial law and postpone elections. I think that's what he wants to do.

So what people can do and what I think is the most—the two most important things is they can show up en masse understanding that they must be restrained. If they get angry, if they lose their discipline, if they attack one of these guys—I mean, I would want to shoot them myself. I would want to make it more expensive for ICE people to do what they do. Let's kill six. But I knew if I did that, we'd be Afghanistan in a week or Iraq. The country would explode in violence and it would be torn apart for 20 years. So, we can't do that.

The other thing we can do—7 million people showed up for the King's Days, and I think that number is now up to about 12 million. That's a lot of power because what all these guys exist on is the money we give them—our spending. So, it's not so easy, but it's not impossible to think that 12 million people who were focused, let's say, on Home Depot as opposed to Lowe's and boycotted Home Depot and wrote letters explaining why, that you could knock one or two percent off their profits. And if you did one or two percent, their shareholders would go crazy and they would be demanding some changes from their board of directors.

And so there's any number of ways that you can do this. You don't have to go on Amazon. You can go on eBay, which was started by a French philanthropist who gave his fortune away. It's hard. I mean Whole Foods in many cases is the only source of organic food for people. It's hard not to—it's hard to boycott Apple computers if you're using them. But there are places you can start and I think it's actually—every time you spend a nickel and you give it to Zuckerberg and you give it to Bezos, these guys are supporting Trump to oppress you.

So I think that discipline and research and AI would help people organize boycotts of stopping the shopping of the most outstanding malefactors in the corporate sector. I think that's about all that we can do right now. And doing the research as many Democrats are to protect the vote, the coming vote, but you know that they would not be behaving this way if they felt that they were going to face the voters. So, they've got something in mind, right? And we have to be ready for it. And I'm going to be the last person to call for violence because when I look at Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, the Kurds, I just watched the—Gaza. I just watched the total destruction of civilization. And I would not want to call that down on my country.

So, I'm hoping that people are going to figure out—the 70 million people that voted for this guy are going to figure out the limits of single issue thinking. What good does a bank account do you in a ruined economy? In a ruined country, in a place where American women can be shot and the people—your government comes out and calls them a terrorist before there's any investigation. I mean, when they get to people like Marjorie Taylor Greene and she sees through it, she can't be the only one.

So, I just think you have to show up.

You started the conversation talking about the class I taught at Harvard.

So, you don't want your protests to become Republican campaign videos. You just don't. So, to avoid that, you have to understand a couple of things. One is that a protest is a ceremony—an invitation that you're putting out there for other people. Nobody accepts an invitation when they're being screamed at. So my first suggestion is let women organize it. Let women cut the macho factor. They'll be more attentive to diverse voices. Everything will be softer, kinder in the organization.

Second, appoint proctors. Give them yellow highway vests and whistles. And their only job is to look for violence. And at the first sign of violence, they blow whistles and the protesters sit down. Let the police take out their aggression on the paramilitaries and whoever it is that's breaking store windows and ruining little people. You don't want those people.

You have to know who the target of a protest is. And I assert that it's never the police. It's never the political people. It is always the American people who are looking for who they can trust. And when you win their trust, you win power at the ballot box, which is, you know, institutional power.

So, how do you do that? You do that by not being violent. You do that by dressing nicely. I know people say, "Pete, everybody wears hoodies today." If it's a ceremony, dress better. It doesn't have to be fancy. The civil rights protesters dressed like they were going to church. They weren't rich, but they were investing the event with the dignity they felt it deserved. If you're out there in hoodies, I understand a lot of people are expressing sympathy with Trayvon Martin. But the audience doesn't know who Trayvon Martin is. What they see is a lot of kids looking like gangsters.

Protests should be silent. Impress the American people with your discipline. Let your signs do the talking. Be absolutely silent. It's not a place to vent your rage. Nobody cares about it. They just put you in a cordoned off place and let you yell for the TV cameras. What makes the video is a burning police car or misbehavior. So that's what your proctors are for.

And the final one is go home at night because you can't tell the cops from the killers. And show up the next morning fresh, rested, disciplined, and standing for what your signs say you're standing for. At least that way your actions will never be turned against you. They're not going to get any campaign videos. You're going to win the trust of the people watching that you can behave with dignity and discipline and they will trust you. And if they trust you, they'll give you political power.

Final Reflections on Vietnam and Political Strategy

Hugh Leeman: Peter, I want to ask one final question here to span the spectrum of what we've been looking at today. You have spoken—perhaps we could put it at one end of the spectrum—of the anger of your father. It's something that you've spoken about that you've inherited some of that and it's been a challenge. Perhaps on the other end of the spectrum, we could put zazen and your time dedicated to meditation as a Buddhist priest and navigating the internal landscape and the internal challenges that we all face, particularly to a time like now, I think perhaps as an entryway to exploring that. You narrated Ken Burns's The Vietnam War series and initially caught flack from some of your leftist friends for its nuanced take. How did you handle that criticism from fellow activists who effectively accused you of selling out and how does—you've had an incredible life and what was the perspective on telling the story of Vietnam because that's such a central key to something then in Vietnam that's very similar to what we're seeing now.

Peter Coyote: Well, I'll tell you. I mean, my politics are far to the left of Ken Burns. Ken Burns I consider a close friend. I have unqualified respect for him. He's meticulous. He's impeccable. He never lies. The opening of the Vietnam series began with something like, "This war was started by good men for good reasons until it went bad." Well, you can imagine what my lefty friends did with that. "Sure, you sell out. These were imperialist fascists. They were this, they were that, they were the other thing." And I just let them holler. And finally I said, you know, there were about three deeply analytical documentaries about the Vietnam War that I saw during the wartime and afterwards. And both people who saw them loved them.

Ken Burns got the entire nation to sit still, learned that five presidents had lied to them. Five generals had lied to them. To meet the people who defeated us, who had nowhere to go, who were always home, who outworked us and out-sacrificed us because they had no option. So, who was the more radical filmmaker?

I watched that film with conservatives. I watched it with military people. I watched it with lefty people. Nobody could put a finger on a lie in it. And so one of the things I tell people who are being political today, I remind them of a critical mistake that I participated in as a young man. When Hubert Humphrey was running for president against Richard Nixon, I was far to the left of Hubert Humphrey. I was much much hipper than him. He was a little Midwestern donut, like a jelly donut, and he was tepid about Vietnam. So, you know, I was militant. I was macho. We were not going to support that shit. And we didn't. And we got Richard Nixon as president. And then we got Ronald Reagan. And we got 20 years of imperialism, anti-environmental policies, anti-feminine values policies, anti-union, anti-civil rights. I mean, a 20-year setback.

So, it's called making the perfect the enemy of the good. If I'd thought about it a little, I would have understood that Hubert Humphrey was to the left of Richard Nixon. He was on my side of the line and I got over my skis. And it's what we did in the 60s—our lack of humility, our aggressiveness about purporting free sex and our own styles and our own this and our own that. We left the bulk of people in the Midwest behind. Made them nervous. They may have liked our ideas, but they didn't want their kids hanging out with us.

And so democracy is a numbers game. So you don't get to be the hippest, most powerful, most macho thinker all by yourself. You don't have any power. You only have power if you accrete numbers. And so one of the things you have to learn how to do is work with people who are calmer, more conventional, more traditional than you are. So they stay in the club. So you realize, you know, some of the things you care about are just not critically important.

So, I spend a lot of time trying to caution young political radicals today that way.

Hugh Leeman: Peter Coyote, thank you very much.

Peter Coyote: Thank you, Hugh. This was a great opportunity.