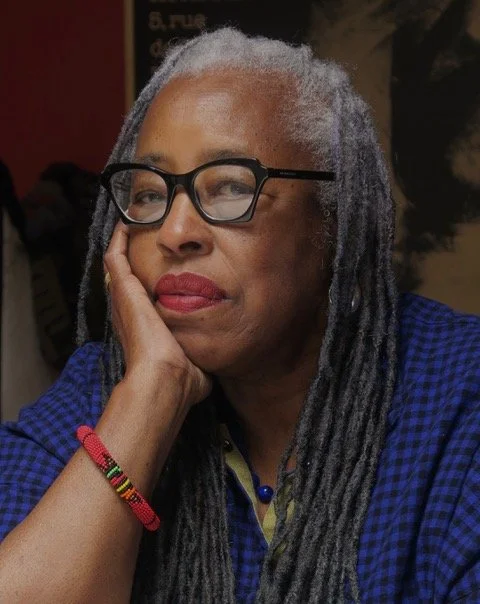

Mildred Howard

Mildred Howard (b. 1945, San Francisco, CA) is best known for her multimedia assemblage work and installations. Her large-scale works have been installed at sites including Battery Park City, New York; Town House Gallery, Cairo, Egypt; Creative Time in New York; InSITE in San Diego, CA; the Museum of Glass in Tacoma, WA; the National Museum of Women in the Arts; and the New Museum in New York. Public artwork has been installed in the counties of Alameda, San Francisco, and Marin.

Works by Howard are included in the permanent collections of the National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Museum, WA; New York Public Library, New York, NY; Berkeley Art Museum, Berkeley, CA; the de Young Museum, San Francisco, CA; Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, CA; the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego, San Diego, CA; the Museum of Glass and Contemporary Art, Tacoma, WA; the Oakland Museum of California, Oakland, CA; SFMOMA, San Francisco, CA; and the San Jose Museum of Art San Jose, CA, among others.

She received Honorary Doctorate Degrees from the California College of the Arts and California State University, East Bay in 2023. She was recently named one of the 2025 recipients of the prestigious Guggenheim Fellowship.

The following are excerpts from Mildred Howard’s interview.

Hugh Leeman: Mildred, you grew up as the youngest of 10 children in a family of activists, and your mother, Mabel Howard, was a legendary community organizer who even sued to stop BART from destroying a black neighborhood in South Berkeley in the 1960s. How did being raised surrounded by activism shape your values? And what memories from your childhood continue to influence your art today?

Mildred Howard: That's a big question. There are so many memories even prior to pursuing BART, fighting to get into the painters union during World War II when they moved to California. I remember her telling me a story that when she went to a boarding school in Conroe, Texas, they protested for some reason and went on a strike, and she ended up being student body president. Later as an adult she worked in a shrimp factory in Galveston, and something was happening with how all the workers were mistreated. I remember her telling me that instead of packing the whole shrimp, they only packed the heads of the shrimp. They ended up getting their way. It was just a part of who she was, a part of our life growing up. If you grow up Black or African American in the 50s and 60s with parents from the south, it was part of your responsibility. It wasn't something separate. It was more a part of you. As a teenager, our home was always filled with political and community figures coming in and out of the house. I just left the memorial for Belva Davis and I saw so many people even much older than I. That was as a result of my mother. There were tons of people there who I knew and who I had met through her—from Congresswoman Barbara Lee to Willie Brown and so many more.

HL: I want to hear your thoughts on some of the stories that you've told throughout your career and then turn the attention toward what you might share with a current or future generation of artists that face similar challenges. There's a story that you once told about a counselor who told you as a kid that people like you shouldn't go to college.

MH: I never forgot it. I was a teenager. I had graduated from Berkeley High School and got a scholarship. My dance teacher said, "Are you applying for a scholarship?" I was surprised because counselors didn't offer advice to people who looked like me on what you should do. I wrote up something and got it. She said, "Well, where should I go?" And she said, "Anywhere you want to." I remembered watching Ruth Beckford who taught Afro-Asian dancing next door from my house where I took my arts and crafts classes. I said, "I guess I'll go there and take classes from her." That's what I did because that's what I knew. I mean, I studied ballet as a child and dance until my mid to late 20s. But it was a great decision I made. It was one of the best decisions I made because what it provided me was discipline. And it provided me with discipline that I carry throughout my visual arts practice. At that time I probably could have gone to UC Berkeley and paid for Miss Beckford's classes, but I didn't. I went to Oakland City, which is now part of the Peralta school system. That was another interesting thing because there I met so many people in the black nationalist movement. Bobby Seale and Huey Newton—I don't know if they were going to school there or what, but they were there all the time. That was a great thing to have happen. I also remember the jazz vibraphonist Bobby Hutcherson setting up his vibes on the lawn on what we call now Martin Luther King between Aileen and 50-something street. It was just a great time to be in this area because the political climate has always been progressive. Shortly after that, the free speech movement, the war in Vietnam—all of that. Seeing Muhammad Ali shadow box down Shattuck Avenue. Going to see James Brown at the Oakland Auditorium or walking two doors from my house to see Leontyne Price and Duke Ellington perform. Those are the kinds of things in addition to the social and political activism that I participated in during that period. I just left the memorial of the news commentator Belva Davis, who I first met when I was about 15. She started this Charms Beauty College and I knew her because of that. I can remember Willie Brown walking down Martin Luther King, which was then Grove Street, because his first wife lived right near me. It was an interesting time, but you don't know that growing up. You just think it's normal. You just think it's the way it is. And it wasn't until years later because you need some life experience to show you.

HL: What was your internal dialogue like all these years since then that's kept you motivated and inspired? What does that sound like if you were to share that with youth today to keep them motivated and inspired if they were to hear something similar?

MH: Follow your mind. Find something that you like to do that you are really interested in doing and put all that you have into it and continue to do it because life, as the great Oliver Jackson says, life be lifen.

HL: Beyond here in the Bay Area you've traveled for residencies to Italy, Senegal, Morocco, Egypt. What stories come to mind from these experiences that have gone on to affect not just your artwork but your worldview?

MH: It puts the United States in perspective. That's what it did for me. It put the United States in perspective in a more global way. And you begin to not believe all the hype. When I first traveled to Egypt, they were saying don't go, this is that, you know, come on. When I went back again, I spent six weeks and I lectured in a city called Minya, which has the largest art school in all of Egypt. I was amazed to see—my classroom, my lecture was in a huge classroom and there were students sitting two at a desk. I had never seen people that were hungry for knowing something outside of their environment. The same thing happened when I was invited by the curator Eddie Chambers to lecture at the University of London Oriental Studies. I was amazed that there were people of color, not all but a lot, coming from all over the country to hear me lecture. I'm thinking what a great job Eddie did to let people know that I was there because why would they know me? I'm just an artist. But it also showed me the hunger or the deep interest in art and hearing a different story than what's perpetuated in the art history books. The same thing happened going to Morocco, going to Senegal, going to Ghana. I love Senegal. Senegal was incredible. The water in Senegal was just like turquoise, and the clothing—men wore bright color suits or caftans made out of everything from lace or eyelet, just every kind of material. I'm thinking, how cool is this? Then you would see these people, especially on Fridays because the Muslims go to the mosque on Fridays, and you see all these people coming out of the mosque and it's like wow, look at this.

HL: Taking that idea of these experiences you're having in different parts of the world, there's a previous talk where you remarked that quote, "The United States is just an idea continuously formed and remade, and the artists who are burdened with the curse of creativity are driven to remake that idea," end quote. In today's turbulent social climate, how do you view the artist's role in shaping that idea of America and in challenging narratives?

MH: Artists create what they see, what they feel. I don't think they always create work—just the act of being, of making. I don't know if I'm an artist or a maker or a person who puts stuff together, but artists create what their imagination gives them, not only their imagination but what they feel, what they see, what they hear. For me, I'm impacted by—I'm not separate from the world because I'm an artist. I still have to pay my rent and all my responsibilities, go to the grocery store. We're not separate from the world, but we do interpret the world in a different kind of way, whether it be music or literature or the visual arts, including filmmaking and all of that. I think the world for me—and I can only speak for me—I'm here and this is how I visually tell my story or a story.

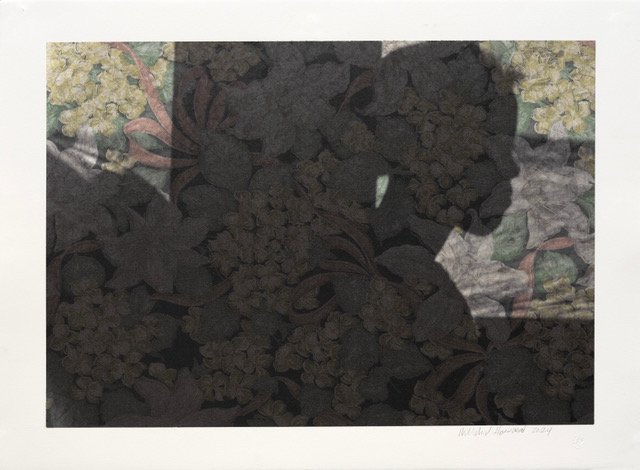

HL: In that story, I want to focus on your two-dimensional artworks, your collage and printmaking practice. It often involves layering antique engravings and maps, text, photographs. How do you choose the fragments of history or culture that you incorporate into a two-dimensional piece?

MH: I guess I'm just made that way. I remember as a child just saying things because I question everything. I'm my own critic and I question everything. I think that's a good thing to be able to question things because one question will take you on a journey. At least it'll take me on a journey and I can go one way or I can go another way or I can go one way and stop and say, "Hey, I see this differently now. Why don't I lay this piece of paper down or why don't I take this material and use it in this kind of way?" The layering of information is similar to the layering of history. Because history is by those who tell the story. It's the information, it's the journey, it's the process, it's the making and the selection of elements that intrigue me.

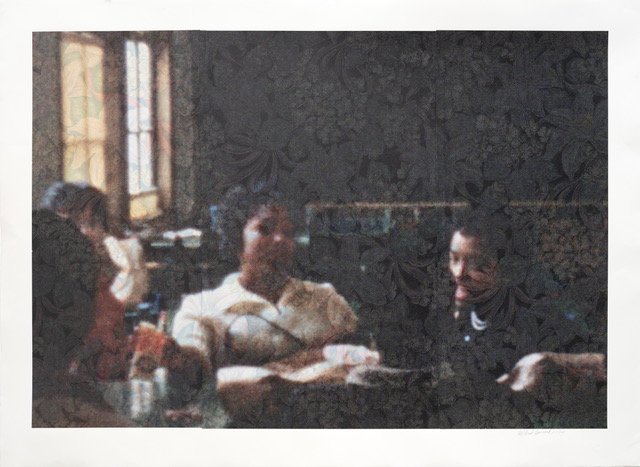

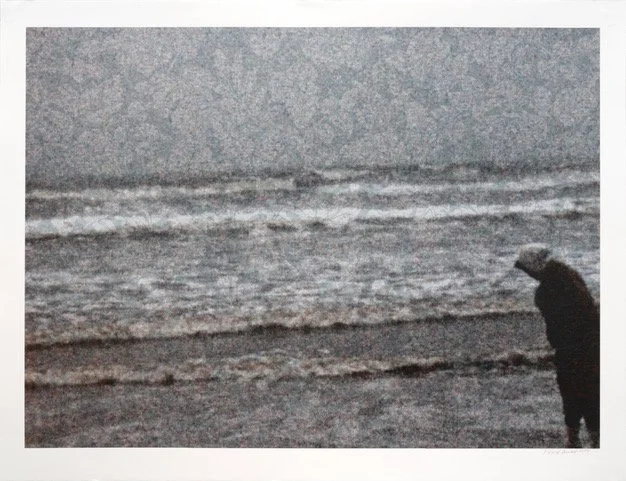

I’ve Been a Witness to This Game, IV, 2016

Media: Chine Colle’ on antique paper

20” x 16” Published at Shark’s Ink

HL: There's one series that has stood out to me. You created a series of monoprints that explore the image of a spade, a symbol that has many layered meanings in culture and language. Can you give context to the meanings of the spade and what inspired you to focus on it for that print series?

MH: I think I did that series at Shark's Ink in Colorado. A spade is a heart with a tail. It's just another element and black folks were called spades. The ace of spades, you know, and those derogatory things. But I try to take those things and use them within a different context and it works within the composition of the piece. I think those were engraved separately. I did one of the hearts even earlier, like the first year they had hearts in San Francisco. I did a giant black heart with a spade on it. I try to have these subtle ways, sometimes subtle, sometimes in your face, ways of representing communities that are not recognized or overlooked. That may stem from my childhood or from that one counselor. God. I wish I could have met him again today.

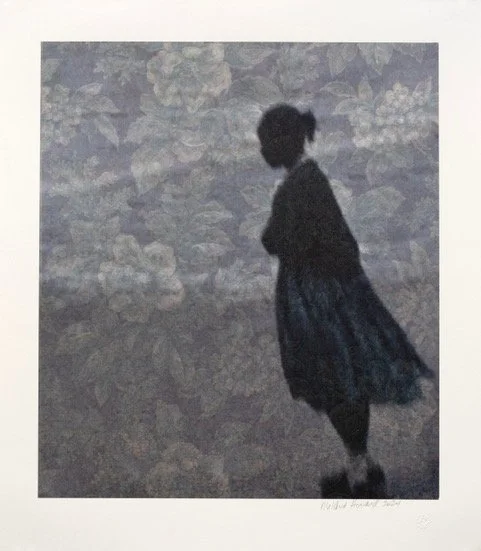

I’ve Been a Witness to This Game, III, 2016

Media: lithography, Chine Colle’ on antique paper

20” x 16” Published at Shark’s Ink

HL: What would you want to say if you met him again?

MH: I would ask him why did he say that? Why did he say that? That's what I would ask him. Why? And what makes him so important that he could say something like that to someone who's just starting or just becoming an adult?

HL: As you say that, as you're just becoming an adult and that sort of youth that we all have, a bit naive at that age, when you heard that in those moments, what was your feeling? What was your takeaway? What was going on inside?

MH: I felt crushed. That someone like that had that much power to say something, and here he was a counselor. Education is a big business. It's good but it's also a big business, or else we wouldn't have so many students with graduate degrees who can't afford rent because they're paying all their money from student loans. We wouldn't have an ignorant person running this country. An ignorant, evil person running this country who when the prime minister of Liberia came to the White House—God, he's such a stupid ass—he said, "Oh, where did you learn to speak English?" Open up a map. Open up a textbook and see Liberia. That's where they speak English. Blacks in this country left and went back to Liberia, which was one of the countries where African Americans could go and automatically be given citizenship after the Emancipation Proclamation. Those who wanted to leave went back to Liberia. And then there are the Africans that were there. They probably have tribal languages also, but they speak English. You idiot. And he's a felon. A 32-count felon running the United States of America.

HL: These challenges that you're speaking of—there's one in particular that stands out. You're at the City University of New York and you do an installation, the piece is vandalized, and the New York City police end up blocking off the street and it was considered a hate crime. You told me previously that you have calmed down as you have grown and that it didn't bother you like it would have when you were younger. Can you talk about this journey of emotional growth?

MH: I don't know if I can talk about the whole journey, but I can talk about the moment. It's like I got you. I got to you and I'm not going to stop. That shows you the power of art right there. Because it brought visibility to all the hypocrisy of this country and the hatred that many people have of people of color. We're not going nowhere. We've been here. I'm just fortunate that I am an artist and I'm around a group of people who embrace diversity. I remember talking with my grandsons and I said, "When you guys go out with somebody, do you first look at what color they are?" They looked at me like I was crazy. No, we don't. That's the difference now. And that's because they grew up here in the Bay Area. That's not to say that they haven't faced discrimination because they have, but it's just different. We have a lot of idiots running the world and they're running scared because the world has changed and it's going to continue to change. The best thing you do is get on into it and have a good time because you're not here but for a minute.

HL: In your art practice, you've noted that you work in various media and that in your words you said that you get bored very easily if you stay in one mode. When you switch from making a large-scale sculpture or an installation to focusing on 2D collages and paintings, what changes for you on the internal landscape?

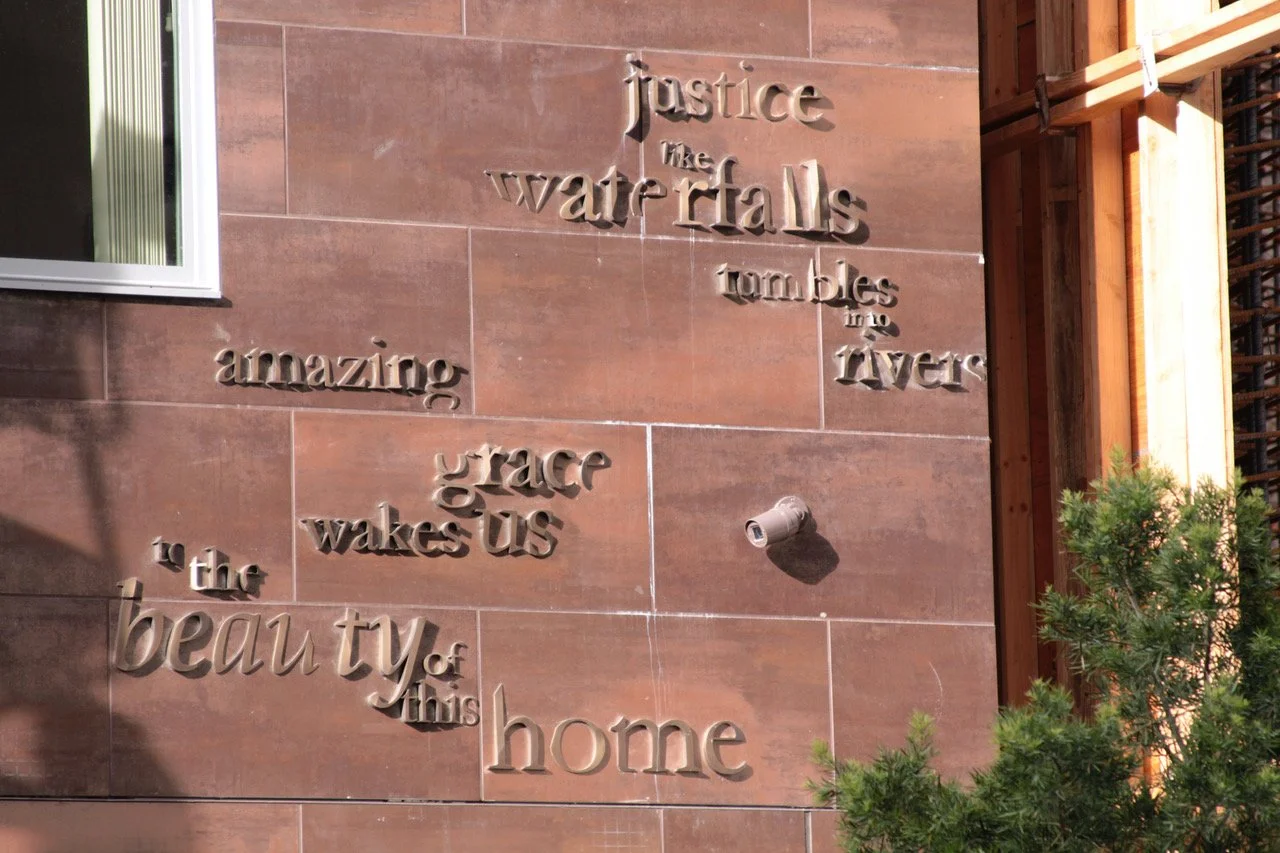

MH: It's all the same thing. It's still making, it's still figuring out problems and how to make things work. While I was working on one of my last big series, I did a series based on film stills. The film I shot when I was 14, maybe turning 15. I found them and I worked on those at Magnolia. Prior to that, probably maybe five or ten years, I had taken a roll of wallpaper, old wallpaper that I found at an antique shop and I said, I want to use this sometime. Later that was happening. While I was doing that series, I began thinking about a piece that I just completed at Fort Point where I shrouded three figures in red fabric. I think you probably saw that one—three figures were at Fort Point and one was at Capp Street. At Capp Street I wrapped Junípero Serra, who was another snake. Religion can do a job on you if you let it and don't use your head. I wrapped all of them in Make America Great Again fabric color—not fabric but color—the red, because my idea behind that is that I'm going to tell a different story and a different story will make America great, and at least it'll make people aware of a different story from a different group of people, but we're all in this same place. So I wrapped Junípero Serra, the guy who made the Star-Spangled Banner, Francis Scott Key, and then the first elected governor and the first elected senator. I wrapped them all in the red. Those three were at Fort Point and they're about 9 and a half feet tall. It just came down because of the government shutdown. It was supposed to be up through this month, but it had to come down at the beginning of the month.

Salty Peanuts, 2000

Sculpture

San Francisco International Airport

Powder Coated Steel, 130 saxophones

First four movements of Salt Peanuts

Commissioned by the San Francisco former Redevelopment Agency

HL: I want to talk more about this project. Some 20 years ago, you were turned down for the Venice Biennale and you had an epiphany saying to yourself effectively, I'm not going to wait to be invited, I'm going to have my own. This leads to the Collaborating with the Muses project. When you began with this, you said, "I want to set the groundwork for other artists." Can you tell about that groundwork?

MH: Collaborating with the Muses is the one that I did at Capp Street or they call it 500 Capp now. I began by reinstalling a former installation. That part of that installation was what was proposed for the Venice Biennale. There was a film that I did and installations in various other rooms. Later that became the Junípero Serra and then the Fort Point one. I did one other as a part of that at pt.2 Gallery in Oakland. I don't know if you know the jazz musician Bill Evans. He has a tune called "Peace Piece." When you listen to it—it's just so beautiful. What I did was I invited musicians that I knew to play the first few bars of that tune and then their rendition of "Peace Piece." The room was painted all white and in a different white were the notes of "Peace Piece" at eye level. You don't see them when you go in there. You have to be in there a minute. In one corner I had a white grand piano. Down low you could hear Bill Evans playing "Peace Piece." On three or four different Saturdays—the first one was Jon Jang because I've liked his music forever. He's an incredible piano player and musician and he did the first four bars and then he mixed it with traditional Chinese musical elements. It was incredible. Then Chris Brown—Christopher Brown is, I don't know if I should say conceptual, maybe he's a conceptual musician, but he plays music that takes me on this visual journey. I had him write the score for a film that I did. I remember telling him, I want you to "monk" this one up for me. He said, "Oh boy, that's a hard one," because Thelonious Monk, but he's good. I had heard Chris play "Straight No Chaser" and my late friend John said that's a hard tune to play and then I started paying more attention to Chris, so I invited him to play. It was Chris, Jon Jang, and then the bassist—I can't think of his name, but all three had their rendition of "Peace Piece" because I was feeling that we all need something like that right now in this space, in this time, because the world has gone crazy. It's just out of control.

HL: I'd like to focus on that idea that it's gone crazy because this brings us to a really interesting thing with your project, the Untold Histories and Hidden Truths, where you're collaborating with the Muses part two and you reimagine monuments of historical figures who oppressed others. What are your thoughts on the broader movement to reconsider public monuments and historical narratives today?

MH: They should never have been up there anyway. I mean, they shouldn't have been there anyway. But I go back and forth. I think that one thing is if we told the truth about them, that would be one way of dealing with it. Just to tell the truth because it could be a real educational tool. Then things change. Some of my work may have to come down at some point. It may not be relevant later. Who knows? Everything's going to change. It doesn't bother me that a lot of them are down because of the atrocities that were perpetuated under their regime. It doesn't bother me.

HL: You have an upcoming show at the Oakland Museum of California and it expands on your Collaborating with the Muses series. For those who don't know, can you give context to this series and previous works and then expand on the idea of how you're approaching this final chapter that will be at the Oakland Museum?

MH: I hope it's not the final chapter. The final chapter of Collaborating with the Muses—yes. I was approached by the director Lori Fogarty and Karen Adams maybe three years ago about doing a big show there. What we're pulling together is work from different decades of my life and some things that have only been shown maybe once. It's a culmination of both my installations, my sculpture or assemblage, and my 2D work. I'm doing one new piece for it. They're going to do a monograph that will accompany the exhibition. It's a lot of work. So I put off having anything else and focused primarily on that and things that I'm doing in my studio. I'm working on a piece right now. But the minute I say I'm not going to do something, I do it because it eats at me.

HL: There's this interesting part of your career where you have said the artist can just be the artist. They don't need to be the psychologist and the social therapist, so to speak. But on the other hand, you are quite the activist.

MH: I don't try to be, but it's not like I have a choice. Would you ask a dentist when you go to have your teeth fixed, "Are you going to have to paint this or you're going to have to go work at Safeway?" Why do they lay all this on us? Because I think that they have to justify the money when you're getting public funds. I don't want to teach anymore. I've done that. Why do I have to go do a workshop now? Making the art is enough. I mean, it's a lot of work. It's work. All this glamorization—no, it's work. But fortunately, it's work that I enjoy.

HL: Looking out your West Oakland window, you had previously observed that everything about the United States is right here in front of me, the good, the bad, and the in between. How does your immediate environment and life here in the Bay Area continue to inform your artistic vision?

MH: I grew up in Berkeley, first of all, and I lived in Berkeley all my life until about seven or eight years ago when I got priced out of Berkeley. Every time I say that, I think about—where I lived in Berkeley was redlined. That was the only place that African Americans and people of color could buy property. My mom said, "These white folks are going to get sick of commuting to Walnut Creek and Orinda and all these places and they're going to come, we're going to die, and they're going to come back and buy this property, and you won't even be able to live here." That's exactly what's happening. That happens not just in the Bay Area, but throughout the United States. I did the piece called "The Dog," which is a train, an electric train, where on all the cars I put neighborhoods that have been displaced because of gentrification. I did it from California to New York and various cities. I have things like the West End, Fillmore, Japantown—maybe I put Jtown. I have Bayview. I have Union City. I have Third Ward in New Orleans, Fifth Ward, and Harlem. Those kinds of things on the cars, those names on the cars just to make people realize that we were here. We were here.

MH: I need all the help I can get because this is how I make—I wanted to be an artist. I could have stayed at UC Berkeley and had a retirement and all of that. Oh, no. Why work for someone eight hours a week when you can work all the time for yourself? All the time.

MH: I was sitting in my car when I wrote that, and that was when I was getting one of my honorary PhDs. I was noticing all the things that were happening while I was sitting there. Plus, it was raining. If you look at a raindrop, the image is inverted or upside down. That took me on that journey of looking at—I can send you what I wrote. I'll send you what I wrote. That's because everything about the world was right in front of me. That was an eye-opening time. I saw parents, mothers with their kids walking too fast, street people, people with their coffee cup and their strollers. It's just everything was right there in front of me. And when people say they don't have anything to say, you just have to look around and it's so much there. It's just so much there. I got two honorary PhDs in a weekend and I was really happy to be appreciated, but I'm thinking, give me the money that it takes to get a PhD and then I'll do what I want.

“As a working artist for over fifty years, there are a few other important things that I’d

like to share with you, to try to set you up for success. For example, I hope that you

realize that art is a business. Art might be your pleasure, your passion; it might even be

something that feels sacred or spiritual — that’s fine. Maybe it is. But it’s also definitely

a business. The line between art making and commerce is mostly in your head. In

reality, there is no line. The sooner you can get comfortable stepping across that line,

with one foot in the studio and one foot in being an entrepreneur, the easier your life as

an artist will be. Learn as much about the business of art as possible. Make that a part

of your creative development. Study it, like you would study a technique or a tool for

making new work.”

Hugh Leeman: Mildred Howard thank you.

Mildred Howard: Yes, thank you. Bye-bye.