Katherine Vetne, Between Worlds, Catharine Clark Gallery

By Deborah Bishop

When you first clap eyes on one of Katherine Vetne’s intricately rendered still lifes—replete with floral-patterned china, lace doilies, stately vases, and etched crystal goblets—it’s not immediately apparent that something sinister is afoot.

But the longer you linger—and the sheer volume of detail relayed in each metalpoint drawing almost demands that you do—the more you find yourself poised in an uncanny valley between designer domesticity and distorted reality: Martha Stewart, say, by way of David Lynch. Each of the scenes is unsettling in its own way, with fractured images, shifting perspectives, raking light sources, objects that appear to float or melt, overturned vessels, and a sense of recent—or impending—calamity. If these were live iPhone photos instead of drawings, we’d be scrambling to press on them like amateur sleuths to determine what occurred just before—or after—the shutter was clicked.

While the depiction of luxury objects and representations of death—intermingled signifiers of material wealth and decay—traces its artistic DNA to the Dutch Vanitas tradition of the 17th century, Vetne’s cultural critiques divert sharply from the religious moralizing of her aesthetic antecedents. Her concern is not with what happens to our material goods and mortal souls after we die (the “you can’t take it with you” finger-wagging implicit in so many of those old masterworks, stuffed to the gills with memento mori), but rather with the corruption and competitive consumption that threaten our life, liberty, and pursuit of happiness right here on earth. That this current exhibition coincides with an unprecedented government assault on human rights, women’s bodily autonomy, and artistic expression is no coincidence.

Portrait of the Artist as a Young Girl

Between Worlds, the name of Vetne’s exhibition, is also an apt description of her upbringing in Newburyport, Massachusetts—a wealthy coastal enclave north of Boston defined by rigid class norms and codified conformity right out of The Official Preppy Handbook. The child of divorced parents, and less affluent than many of her cohorts, Vetne (who is now 38) describes feeling discomforted by the rigidity of the social strata—like an embedded anthropologist, she made note of the whispered judgements and social tensions simmering below the surface of propriety. Knowing from a young age that she wanted to become an artist only exacerbated Vetne’s feelings of otherness, as did her nascent observations of what it meant to be female in this environment. “Long before I knew what feminism was, I sensed something was off,” shares Vetne. “One day, I stumbled on this autobiography of a Saudi princess describing the horrendous expectations around gender and class in her country. I felt all this righteous anger—and then I was struck by how people were being treated right here at home—and that has stuck with me.”

In graduate school at the San Francisco Art Institute, Vetne took her twined interests in consumerism, feminism, and power and used wedding culture—specifically gift registries—as a jumping-off point for her work. From the prosaic to the aspirational, these wish lists are a curated arsenal of all the stuff a couple deems essential for domestic bliss. Between the blenders and the cashmere blankets, one category jumped out: “Leaded glass crystal is such a common wedding present across all different eras and populations, and a totemic presence on the hostess’ holiday table,” says Vetne, who settled upon crystal as both subject and medium. She scoured eBay and thrift shops for iconic pieces—such as Waterford pitchers, punchbowls, and the like—and drew detailed studies in which the etched glass appears to be melting, in the way that fairy-tale endings can take a turn after the vows are uttered. Then, as now, Vetne works in metalpoint on top of prepared chalk panels, a technique that reached its zenith in the Renaissance. “I’ve always been attracted to arcane media,” says Vetne with a laugh. “Metal—in my case gold—is ideal for detail work, as it doesn’t wear down as quickly as graphite. And it gives the drawings this almost luminescent glow.” One material not available to Renaissance artists was steel wool, which Vetne fashions into brushes to cover larger swathes of background.

Moving into three dimensions, Vetne took crystal objects and reversed the creation process, melting and slumping the once-cherished keepsakes in a kiln, then coating the puddles and contorted shapes with high-gloss silver nitrate—a golden, reflective surface that highlights the piece’s decorative patterns—or lead sulfide, which is closer to the color of pewter. In 2018, Vetne was included in the show Heavy Metal—Women to Watch, at the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington, DC, where her sculptures were mounted on the wall beside her drawings and perched atop columns, where they appeared to drip over the sides.

Every Table Tells a Story

Vetne’s current show at the Catharine Clark Gallery (through January 3, 2026), includes four large metalpoint tablescapes, four intimate chiaroscuro object studies, and Indulgences, a series of fifteen lead crystal pieces—candelabra, vases, pitchers, gravy boats, goblets—whose functions have been subverted by being slowly melted in the kiln and bent into new configurations, like a scene from Cocteau’s Beauty and the Beast as seen on acid.

Vetne’s still lifes are populated with objects that are freighted with associations—from Lenox china (makers of bespoke dinnerware for six presidential administrations) to Capodimonte porcelain flowers. That these are not exactly current markers of cutting-edge taste is intentional: instead of distracting us with niche designs culled from shelter publications, Vetne has opted for more universal status symbols from a previous era. “I’m channeling the kinds of spaces I grew up in,” says Vetne. “And in some lofty spheres—political realms, royal families—these traditional objects and aesthetics are still very au courant.”

Sharing a name with the show, the work Between Worlds (2025) plays off the Vanitas genre with a stately Lenox vase filled with parrot tulips past their prime, the splayed petals a garden-variety reminder of mortality. The impressive centerpiece has been fractured by being reflected three times in two mirrors, challenging the viewer to decide what is real and what is fake—an increasingly familiar exercise in a world of fungible truth, A.I., and pseudoscience. Tulips, of course, also harken back to the tulip mania of the Dutch Golden Age, when a single bulb could fetch as much as a house, before the market crashed in 1637 and demolished fortunes overnight—a speculative bust-and-boom cycle built on smoke and mirrors not unlike, say, sub-prime mortgages. When it comes to consumer goods, from Louboutins to Labubus, what do we treasure because of its intrinsic value, and what do we crave because of societal expectations?

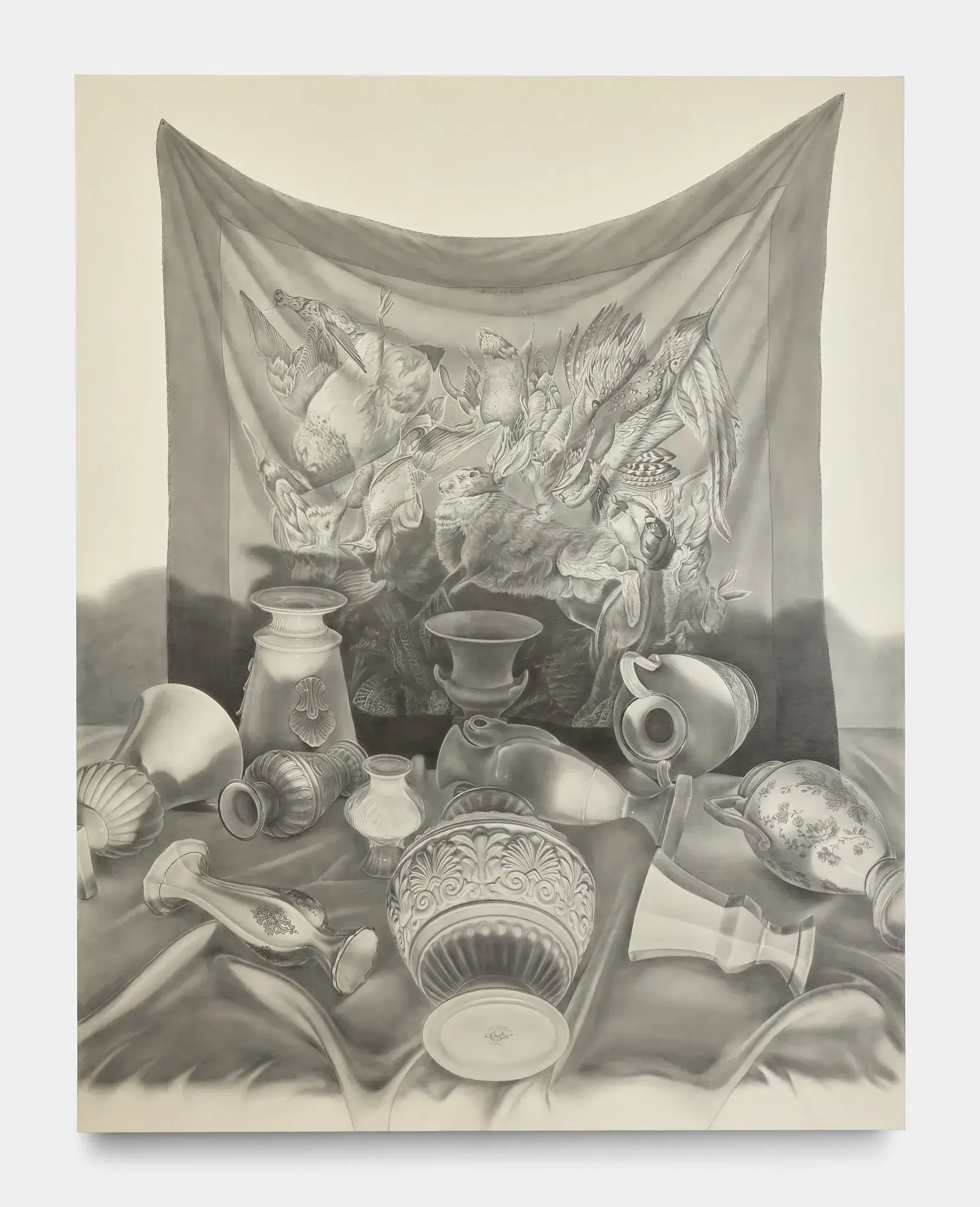

When Vetne set up the props to draw Death in the Pot (2025), massively scaled at 70 x 55 inches, she tacked to the wall a vintage Hermes silk scarf (titled Game) patterned with enough dead birds and rabbits to make a Dutch merchant blush. “I wanted to treat this luxury object as casually as any animal carcass,” says Vetne (a vegetarian). “I’m interested in how the prey and predator relationship acts as a metaphor about all kinds of power imbalances in our society.” The foreground is strewn with overturned Lenox vases arrayed like ancient artifacts around a central urn from the company’s “Athenian” collection—harkening to a halcyon time when secular and rational thought flourished.

The representation of prey goes from top shelf to lowbrow in Savoir-Faire (2025), in which a fancy table set with fine china, lace-trimmed napkins, and crystal glasses shares space with a flea market figurine of a hunting dog toying with a hapless rabbit. The depiction of violence for the sake of sport echoes whatever debacle has recently taken place amidst the rumpled linens and overturned goblets. “I wanted to evoke the aftermath of an event that has been tainted by something unsettling and leave the viewer to imagine what might have transpired,” says Vetne.

While three of the large-scale works pull us right up to the table—where we look on like a guest who is puzzled but composed—our gaze hovers over The Hunt (2025). Beneath us, two overreaching autocrats, Napoleon and Julius Caesar (in the form of an unstoppered Avon cologne bottle) lay toppled, and—as a final indignity—reduced to tchotchkes. Funerary Capodimonte flowers dot the table, along with a meat tenderizer and a seafood fork, two culinary “weapons” used to pummel and pierce flesh. This vantage point grants us greater insights into the bigger picture, and—by extension—the potential for greater agency.

Vetne says she looks forward to exploring this more empowered perspective going forward. Rather than contemplating a scene of violence or chaos with polite bemusement, we may be asked to take up arms, make a move, pick a side. As we are reminded more each day, the line between passivity and complicity is very fine indeed.