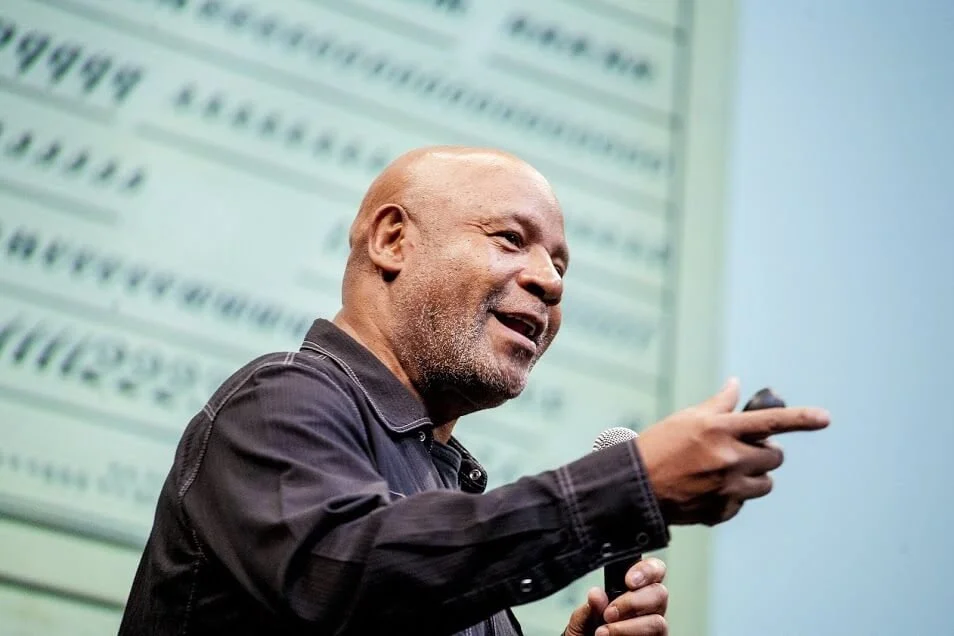

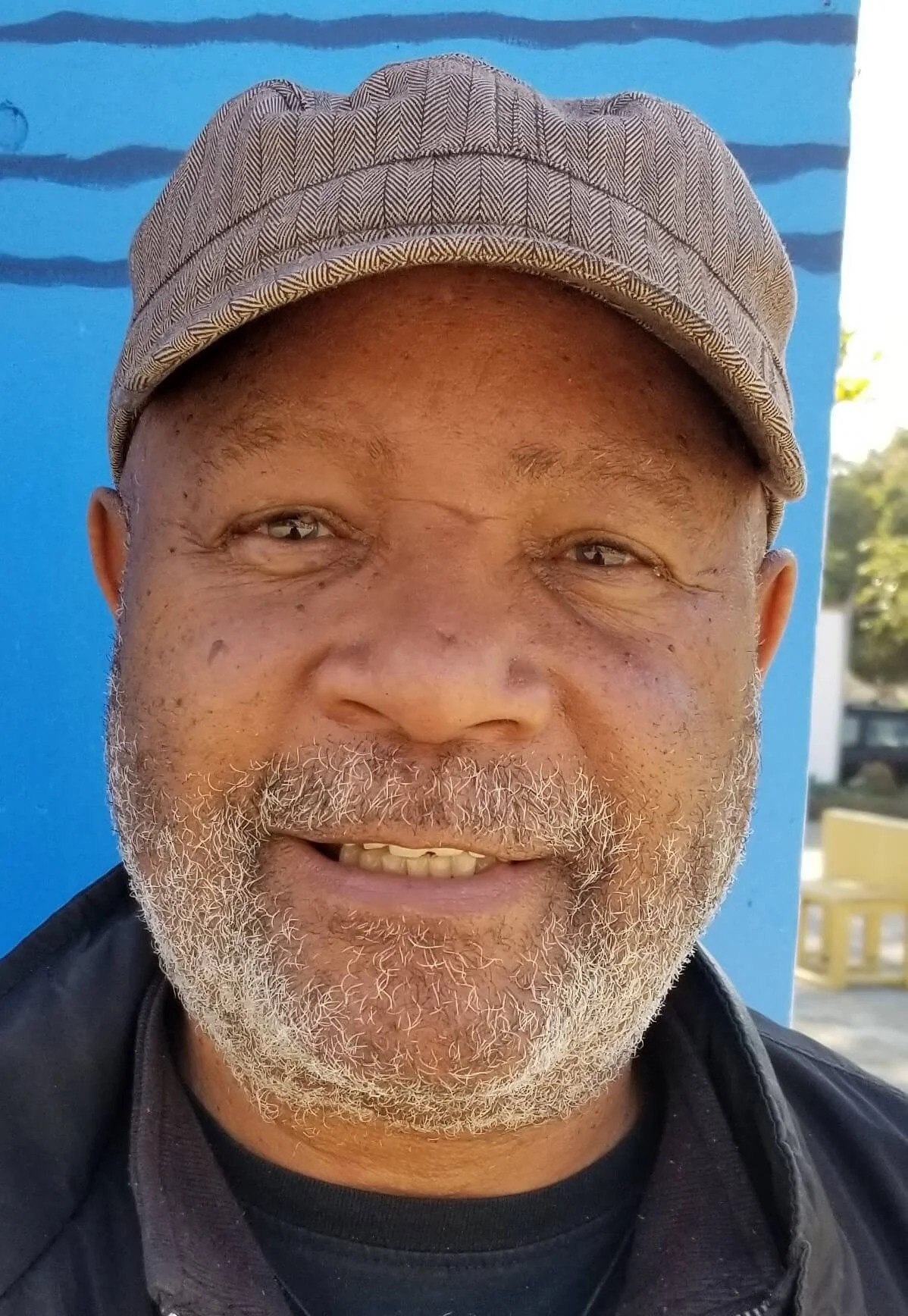

Emory Douglas

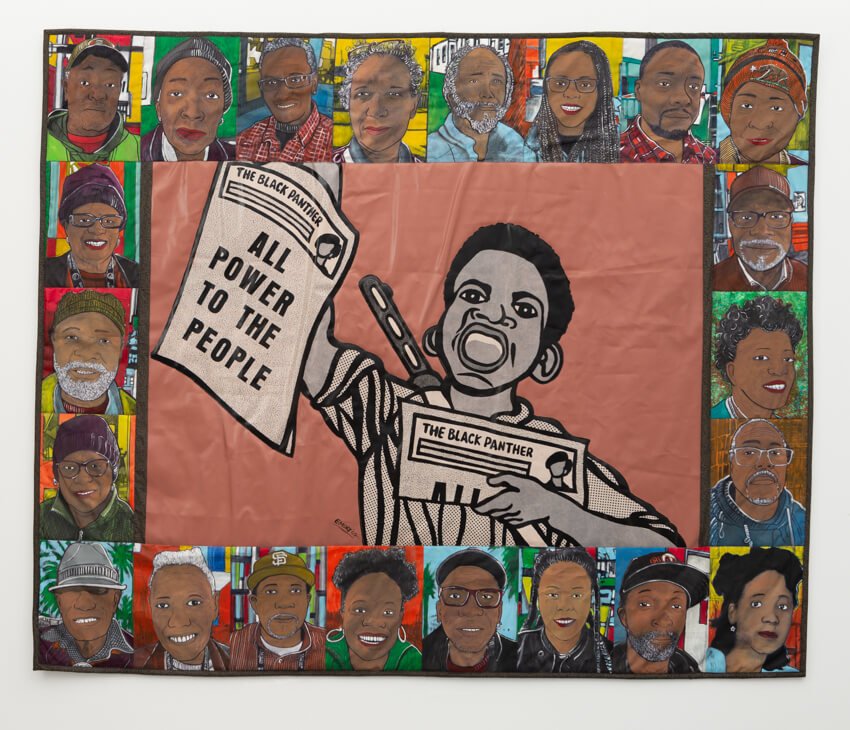

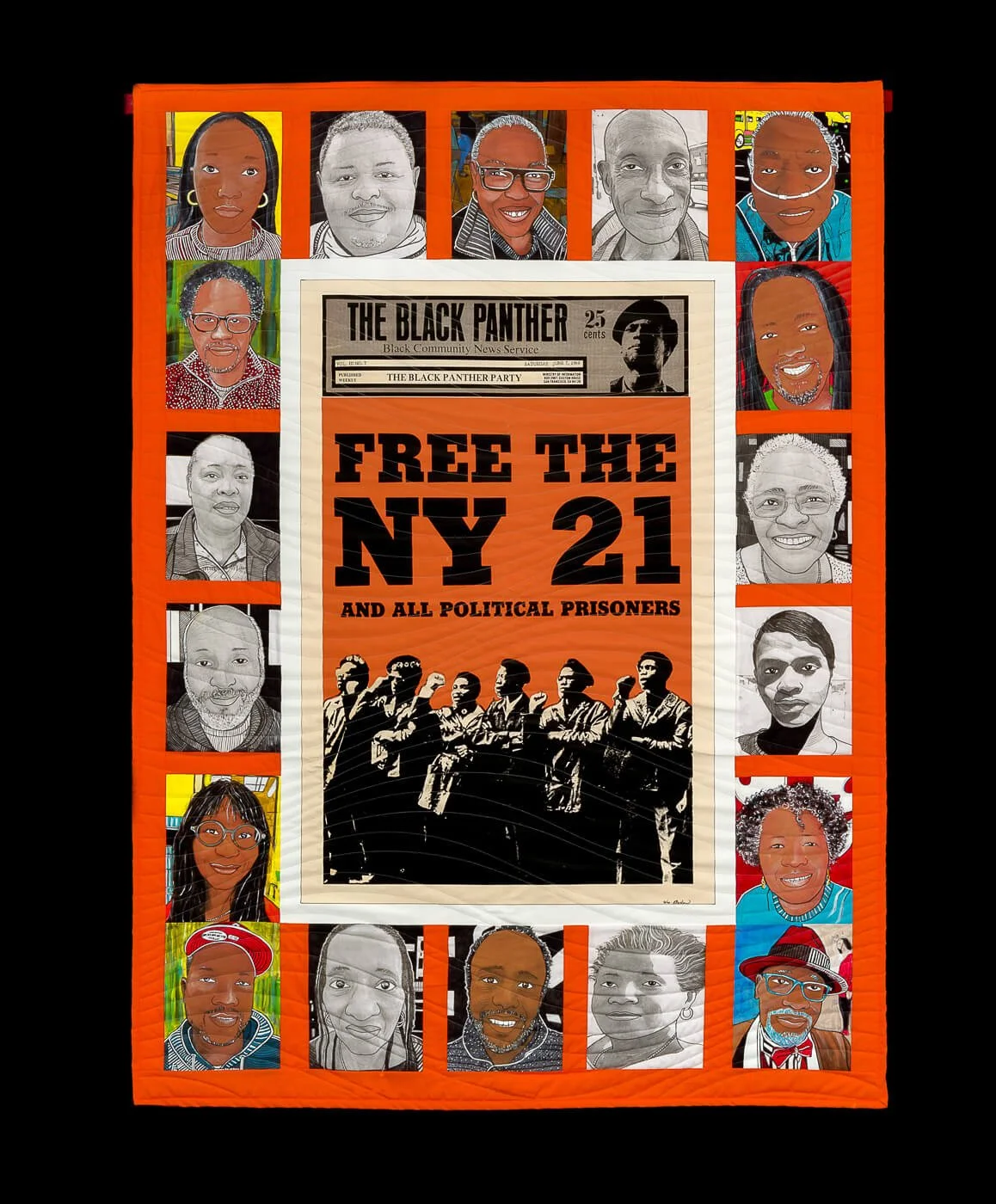

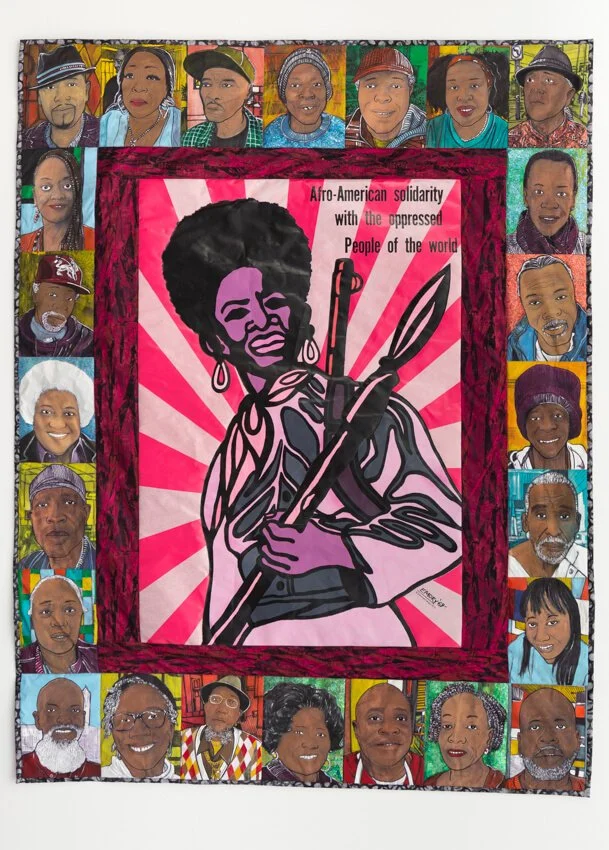

Emory Douglas is a revolutionary graphic artist and cultural worker whose images helped define the visual language of the Black Panther Party beginning in 1967, when he became its primary artist and Minister of Culture. Best known for his searing posters and newspaper illustrations—especially for The Black Panther—Douglas fused bold linework, high-contrast printing aesthetics, and direct political messaging to expose state violence, poverty, and racial injustice while affirming Black dignity and community self-determination. His work functioned as both art and organizing: it translated complex political ideas into widely legible symbols that circulated on walls, in publications, and in public demonstrations.

Douglas has received the AIGA Lifetime Achievement Medal (2015), induction into the Society of Illustrators Hall of Fame, an honorary Doctor of Fine Arts from the San Francisco Art Institute (2019), major retrospectives at institutions like MOCA Los Angeles (2007) and the New Museum (2009), the landmark monograph Black Panther: The Revolutionary Art of Emory Douglas, and even an official “Emory Douglas Day” proclaimed by the City and County of San Francisco on May 24, 2019.

The following are excerpts from Emory Douglas's interview.

Introduction and Accomplishments

Hugh Leeman: Emory, you have a list of impressive accomplishments from the Minister of Culture of the Black Panther Party to American Institute of Graphic Arts Lifetime Achievement Medal, induction to the Society of Illustrators Hall of Fame, honorary doctorate degree, as well as major retrospectives of your art from the Museum of Contemporary Art in LA to the New Museum in New York City. With all of that, what do people need to know about the person behind those accomplishments to better understand who you are and what you've dedicated your life to?

Emory Douglas: Well, I'm just an everyday person, common like most people, you know, overcoming the obstacles and the challenges within life on life's journey, and that reflects in the work that I do as well.

Early Life and the Move to California

Hugh Leeman: I want to hear about that journey because you've had an incredible journey and it starts in Grand Rapids, Michigan, and you end up in the Bay Area, the San Francisco Bay area of California in no small part due to your asthma. Now, this move changed your life and consequently through your creativity has impacted countless people through your artwork, through your activism. If you didn't move to the Bay Area and get involved in the arts and activism, who does Emory Douglas become in small-town Michigan?

Emory Douglas: Well, I wouldn't be who I am. I can say that as a person or as an artist or what have you. I was very sickly, so I may have been sickly the rest of my life. You never can tell on my journey.

Reflections on the Past

Hugh Leeman: Now, you've told many stories about the Black Panthers and your art in various interviews and talks over the several decades here. What is the part that for you remains an internal question mark on the personal journey of your past and your current activism?

Emory Douglas: Well, I'm always questioning what's going on in the real world and issues that are concerning quality of life issues. That's always in my thought process. That's what comes about all the time.

Art in the Hands of the People

Hugh Leeman: Let's focus on the quality of life issues and what's going on in the real world because you dedicated an incredible part of your creativity to putting art, so to speak, in the hands of the people through your artwork that was on the streets, through passing out ideas and information at rallies and such. What was the importance of having art in the hands of the people as opposed to the focus being on institutions or commercial galleries?

Emory Douglas: You got to understand, ours was an alternative institution to those institutional galleries. Ours was a reflection that the community was a gallery, so we posted work on the walls of the gallery so that people could see it on their way to work, wherever they were going on their daily life because they didn't have the time to go to galleries, nor were they of that class at that time, or many of them did not go to galleries in that context. The artwork comes out of that and it comes out of the context of the organization, the alternative organization Black Panther Party, in the context of our perspective of what it represented and what it meant, sharing with, enlightening and informing, educating the community about issues. Those who are not a reading community can learn through observation and participation. They can see the artwork and get the gist of the stories. It was broadening the scope, the landscape of how people can see the work and do the work.

Current Issues and the Role of Art

Hugh Leeman: In 2023, you created a cover for Art Forum magazine and it was dealing with modern issues. What causes or messages feel most urgent for you to address through your art in this current moment?

Emory Douglas: It's quite a few. We're dealing with total fascism now in the context of what's going on in this country and around the world in the context of this country and this leadership. You got quality of life issues. You got the mass unemployment issues. You got educational concerns. You got health, quality of life health issues, all those things. The immigration issue, all those.

Hugh Leeman: With those issues that are so pressing and so large, what role can art play in those issues?

Emory Douglas: Art can be a visual interpretation of those issues that might have some kind of impact in relationship to be inspired by or to be inspired with. It's a language. It's a way you communicate. Art is a visual language and you communicate. You see it every day, 365 days a year. When you awaken in some form, shape, or fashion, your senses are going to get some form of artwork, art, visual art, performing arts, all those. You're impacted by it all the time. That's the power of it. It's a language.

The Origins of Political Art

Hugh Leeman: That language of art. Who was it or what was it? Where does that start for you that influenced you, that gave you that sense that I can do this, this is important, and this is powerful, I should be doing this? Where does that come from?

Emory Douglas: That evolved. That's the whole process, you know, it evolved. The basic foundation is the politics of the Black Panther Party and being involved in the Black Arts Movement before that and coming in conscious during the Black Power movement when Black people began to define themselves, how they wanted to define themselves as African-Americans as opposed to the colonial name, the colonized call Negro and what have you, and resisting that. It comes from out of that, evolving out of that whole process of development.

The Black Panther Aesthetic and Digital Activism

Hugh Leeman: You mentioned these pressing issues that are very much reflective of our current day, referencing immigration, fascism, and so on, taking this idea of other things that are taking place today that are impacting the entire world with the digital world, the internet and so on. The legacy of the Black Panther aesthetic, looking around today, Black Panther imagery and aesthetics, it still pops up from t-shirts to gallery walls, museums. What is the enduring legacy of the Black Panther art style in today's visual culture of protest?

Emory Douglas: Well, it has been inspired by young researchers and people who kept that spirit alive, but it's much more than the t-shirts. Maybe that'll guide those who just think symbolically, think of it as attirement or something you wear, to want to investigate into it. There's many things they can look into today that's online that speaks to the issues, what we were about in that context.

Hugh Leeman: That idea of that context of looking at things online with this new generation of youth activism. What are your thoughts on the transition from the physical art and print propaganda to digital activism?

Emory Douglas: It's a tool. It's all a tool to use to enlighten, to inform, and get the message across or what's been trying to be talked about. It's a tool that can be used. As we know, when a tool becomes very powerful, you have the system try to shut it down, try to limit it in any kind of way it can from having that access of using it in that context. It's a powerful tool. With it you can reach millions of people or volumes of people that you could not reach otherwise in historical past in a matter of hours or minutes. It can have a great impact.

Global Experiences and Universal Resistance

Hugh Leeman: Amidst that idea of that great impact, this is really interesting because a part of your career has been working with different communities all over the world. You've collaborated with Aboriginal artists in Australia to community mural projects in Harlem and Manhattan. What have these global experiences taught you about a sort of universality of art as a form of resistance?

Emory Douglas: It may be transcended differently in different cultures and ideas, but the commonality is the quality of what is talking about, the message of dealing with social justice concerns that transcends borders and communities and cultures. In that context, I think artwork has been inspired with and inspired by those cultures and those places I've traveled.

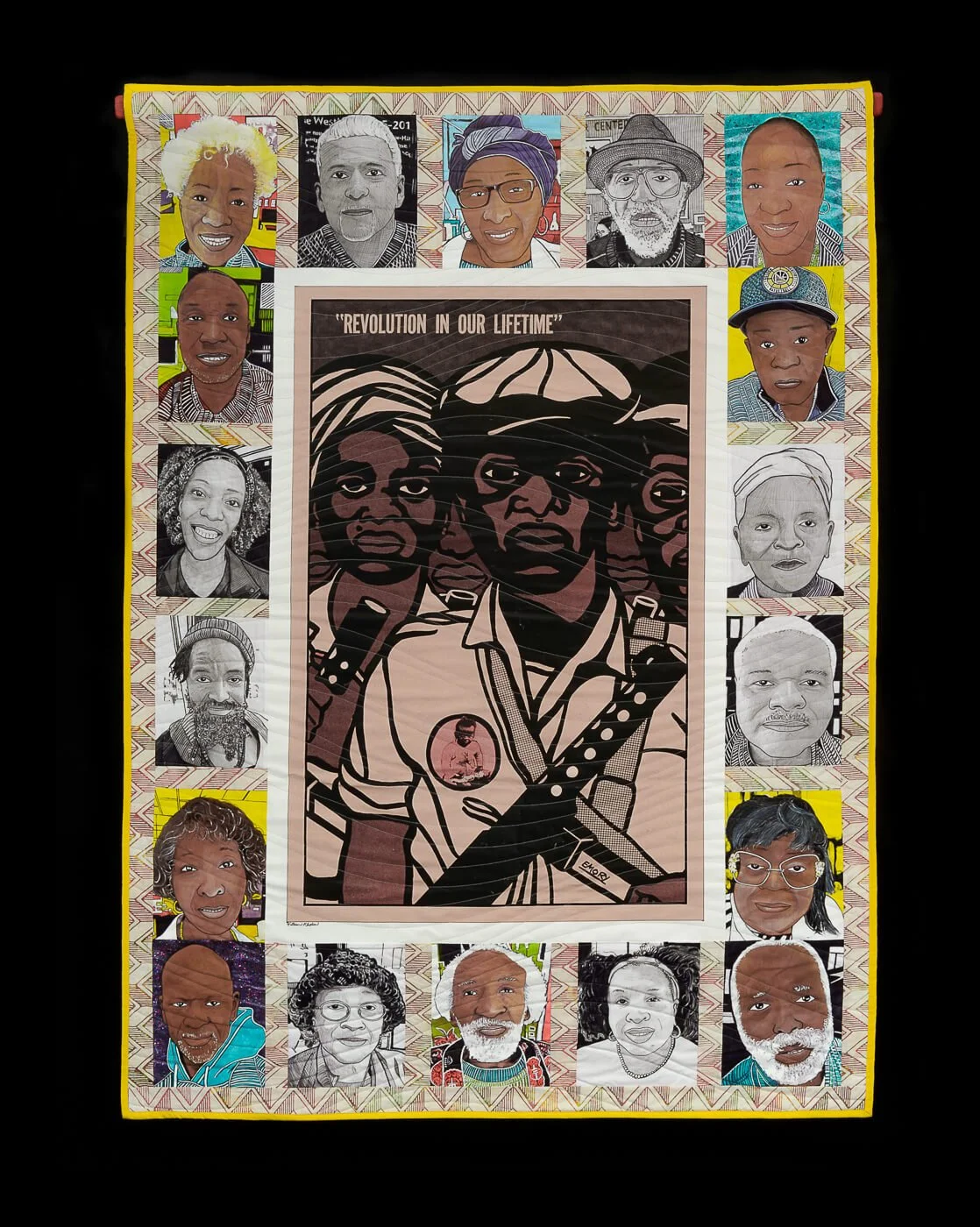

Current Exhibition

Hugh Leeman: Going from those places that you've traveled to right here where you live in the San Francisco Bay area in California. Right now you have a show at the African-American Art and Culture Complex. What are the issues that you're looking at in that show?

Emory Douglas: Rio is the curator, him and Roslyn McGary, his assistant who's working with him. They're the ones who curated the show. It's historic, from some of the stuff I've done prominently up until now, going retrospective of some of the work I've done historically between the Panthers up until this point. It's dealing with artwork and dealing with social concerns and issues at any given time and the processes of my creativity.

Hugh Leeman: What are those issues that you've been dealing with?

Emory Douglas: Police abuse, police brutality, murder, healthcare again, food, quality of life, lack of food security, insecurity, homelessness, all those things apply in the work itself and continue to in the work itself. Compassion, love, respect, all that's in the work.

Evolution as an Artist

Hugh Leeman: It's impressive. You have this career that spans several decades of touching on these issues, focusing on these issues, creating around them, collaborating around them. If you were to compare a piece of your art that you made in say 1970 to one that you made just the other day for this exhibition, what differences do you see that reflect how you personally have grown as a person?

Emory Douglas: The work during then came out of that period, a very hostile, provocative period. So maybe the art even now is hostile and provocative, but the evolution and the involvement because of the battles and challenges that took place during that time had evolved, from limited inclusion to more inclusion into a society that still needed to be transformed. At that time, the artwork was more in your face, more meant to be provocative but not a distorted interpretation but a provocative interpretation, and it came out of the culture and the language and all things that we were creating at that time. I think that's maybe the difference between now and then and how I approach the work.

Love Over Hate

Hugh Leeman: That idea of how you approach the work and the process. There's something I think that's really a testament to the content of your character. It's very impressive. The Black Panthers drew a line between hating oppressive systems versus hating people. You summed it up once in a talk you gave in which you said, quote, "We didn't hate people because of the color of their skin. We hated the inferior education, indecent housing, the billy club. We didn't stoop to the level of the racist to hate people." End quote. How did you personally manage to keep bitterness or anger from turning into blind hatred and what advice would you give to activists today about keeping humanity at the center while still fiercely resisting injustice?

Emory Douglas: You had to be enlightened and you had to be informed and become enlightened. That was the philosophical perspective of the Black Panther Party. When you evolve, you grow to understand because the system itself is predominantly a white institutional system. You can paint with a broad brush, but if you become enlightened, you begin to understand it's the system. It's not everybody. It's the system itself that you have to transform and change. Sometimes people can get caught up in the skin color and what have you.

Early Influences and Mentors

Hugh Leeman: Amidst that system that you're talking about, there are individuals or even in some cases institutions that are the exception to that racist or oppressive system. Who are those people for you that were the mentor or the nurturer, the inspiration that helped guide you?

Emory Douglas: When I was a youngster coming up and I was in and out of those juvenile institutions, from there going into just being encouraged by family, whether I wasn't doing political art, just doing art like kids. I was being encouraged whether they liked it or not, saying you're doing a great job and continue on. Those kinds of things when you're growing up and you become to realize as you're growing up what you've seen as a youngster. I recall as a youngster I used to see these two Black men who used to come on the TV in San Francisco when they would come to town. That was when we had black and white TV in the mid-50s going up into late 50s and 60s. I would be curious because they always had the reporters there and that was W.E.B. Du Bois and Paul Robeson. I remembered that later on. W.E.B. Du Bois had a socialist office four or five blocks from where I lived on McAllister that had been firebombed. I said, "Oh, okay." He was in town. They were talking about it because I had seen it before.

When I started working at the Black press, they asked me to come over to work for them after the Black Panther Party, the Sun Reporter. I began to look at their archives and Dr. Carlton Goodlett was then the owner of it. He had all kinds of photographs of him with Du Bois, with Paul Robeson and what have you. They served as a form of inspiration.

The Black Arts Movement

Hugh Leeman: At what point do you start to feel like this is going to be, you know, because you were making art, it wasn't necessarily political art. You had your family encouraging you. At what point did you think like, hey, this is something I need to do? This is something I need to focus on because that's a big commitment.

Emory Douglas: When I got in the Black Arts Movement and I was doing art for Marvin X, who was a poet who had this street theater, they had a collective of poets. They used to have me do the announcements from time to time, flyers for whatever they were doing. Then when Amiri Baraka, then LeRoi Jones, came out to San Francisco State, I was at City College of San Francisco and I was in the Black Arts Movement during that time. Stokely and Rap and all those used to come to town. I had did some of my first portraiture, caricature art that I did was of Stokely Carmichael and H. Rap Brown during the rebellions and stuff that took place during that time and being in the Black Arts Movement.

Marcus Books did the first print, the first art posters of my work. I was introduced to them when they were downtown in the Tenderloin area before they came back to the Fillmore. All that being in the Black Arts Movement, the Black consciousness movement during that time and being at San Francisco City College where I went. A young man, a brother named Roland Young who was a well-known jazz musician on the radio, was out there at that time organizing to change the name from the Negro Students Association to the Black Students Association. They knew of my work because they were all part of the Black Arts Movement in some way or other. They wanted me to contribute flyers and stuff to that effort. My art became part of how people were interested in the work that I was doing. I did some things, characters of Rap and Stokely, and they appreciated that. That gave you a sense that you were doing something that was relevant. I think that became foundation, and then being in, coming, joining into the Black Panther Party and how they identified with the work and the comrades in the party, that played right into feeling that you had something that was bigger than yourself.

Creating the Black Panther Newspaper

Hugh Leeman: Let's pull on that thread a little bit further here. The comrades of the Black Panther Party. Can you walk us through the newspaper and the production of the newspaper? For example, from concept, you're all sitting around throwing out some ideas to the actual final print when it becomes a physical thing that people could have in their hands. To what extent did Huey, Bobby and others in the Black Panther Party leadership suggest themes or images or give feedback on your designs?

Emory Douglas: First, to respond to that part of the question, only about maybe a handful once they realized that I understood the politics through the artwork. I had the green light to create whatever I wanted to create.

In the beginning, the paper was, we didn't have a national headquarters when I came in the party about three months after its inception. The party started October 1966. I came in around late January, early February of 1967, transitioning from the Black Arts Movement. There were some brothers who I knew who kind of mentored me, older. One of them was a brother named Hank Jones who was one of the San Francisco 8 that came up a couple of years back here in San Francisco where they were charged with something that happened 40 years ago which they were finally exonerated of.

What happened was he said they were planning a meeting to bring Malcolm X's widow to the Bay Area and they wanted me to do the poster because of the Black Arts Movement. I went to the meeting and they said that some brothers would be coming over the next week and they would let them know if they're going to do the security or not. When they came over the next week, that was Huey Newton and Bobby Seale and I knew that's what I wanted to be a part of. I asked them how could I join after that and they had a business card. They gave me the card and I called Huey and Huey scheduled to go by his house and hang out with him. Then he showed me around the neighborhood. We went by Bobby Seale's house and that was my first involvement, transitioning into the Black Panther Party during that time.

At the same time during that meeting, they were trying to get Sister Betty, they weren't getting any response back from Sister Betty Shabazz to come to the Bay Area. They said, well, there was a brother who was in prison who was a follower of Malcolm who was staying at his lawyer's house and just got out of prison and they were going to see if he would write a letter on their behalf to her and maybe she would respond. That was Eldridge Cleaver.

I went up there with them to the house and he agreed to write the letter and that's when she came. When they did the security and they met her at the San Francisco airport, escorted her off the plane, the first place she wanted to go was to meet Eldridge Cleaver at that time because she knew he was a follower of Malcolm and he was working at Ramparts magazine in North Beach. They took her there. In the context of that, they knew of Eldridge but never had met him. They had the vision of the paper and they were trying to connect with him to see if he would be a writer for the paper. That's how they began to communicate with Eldridge, talk with him all the time about working on the paper.

We had a place called the Black House in San Francisco. A lot of cultural events went on. Eldridge stayed upstairs. A lot of cultural events went on downstairs. Stokely, Rap, Amiri Baraka, Sonia Sanchez, all those used to come through there. That became the place. They used to talk to him about why don't we, they knew of him as a writer and they were trying to connect with him.

I remember going fast forward to around April. I remember going to the Black House and Eldridge and Bobby and Huey were downstairs at the table in the dining room area and nothing was happening. It was daytime. When I went in and I started talking with them, I saw Bobby working on this first legal-size sheet of paper which was about the murder of a young brother in Richmond called Denzil Dowell who had been killed by the Richmond police. He was saying that was the first issue of the Black Panther paper done on the typewriter. Bobby was doing the masthead for the masthead.

I saw him doing that because I had been hanging out all up since late February. They said, "Well," and I told them I could help them improve it because I still had materials from City College that I was using and that I could go get it and come back. He said, "Okay." I went and came back. By the time I came back, they were finished with that. He said, "Well, you seem to be committed with this and we're going to start the paper and we want you to be the revolutionary artist and that'll be your title, but then you may eventually become Minister of Culture." This came out of a long discussion going back and forth.

That's how the foundation of, they were still coming over there for the purpose of trying to recruit Eldridge to be the writer for the paper. They used to come over there when the cultural events would be going on downstairs. They would always go upstairs to connect with Eldridge because they knew of him and his writing. Eventually Eldridge agreed he would work on the paper. He started out at his lawyer's house and we worked because we didn't have no place. The materials that I had from City College were the foundation of doing the pre-press preparations, making up our own layout sheets and stuff like that, cutting and pasting from the natural light of the windows, coming through the windows or lamps, what we had, using regular tables, no layout table, none of that, just that basic material that I had and the basic understanding that I had of it from City College. That's how the paper evolved from there.

It wasn't like over a period of time we began to have our headquarters. When we started beginning our headquarters, we would always develop a darkroom, a layout room, production room for where we would put the paper together. Before then, we could pick it up like take it from house to house. There were places where sometimes we had apartments that we had to do it because Eldridge was beginning to do a lot of talking and speaking and other comrades, people who came in and worked with us who had the skills, the writing skills and stuff, were dealing with the editorial part of the paper. We had to go to apartments, had to figure out how you're going to do that. Sometimes we'd get two horses that you put under the cars to keep them up and get a wooden tabletop, put that on that, that became the layout table. All that makeshift stuff went on in regards to putting the paper together.

Relationships with Black Panther Leaders

Hugh Leeman: You've just mentioned a number of very influential names here from the history of the Black Panther Party. What were your relationships like outside of what we might call the work context? What were your relationships like with say Eldridge or Huey in just day-to-day life? What were those conversations like?

Emory Douglas: Before COINTELPRO got into it, they had a good relationship. What happened was Eldridge, because he was on parole, could have been in violation of his parole working with the Panthers. But because he worked for Ramparts magazine, which was a kind of liberal progressive magazine, they allowed him to follow and cover the Panthers as a reporter. Therefore, he was not in violation of his parole when he was working on the newspaper in the beginning.

We had our relationship with others. We had good relationships at that time with Stokely. SNCC was about to disband. Huey and Bobby drafted Stokely into the Black Panther Party and also H. Rap Brown into the party. They used to come up. They had somewhat of the same kind of vision that the party did in relationship. Plus, not only that, Stokely and them were working in Lowndes County where the panther symbol comes from, Lowndes County, Alabama during the civil rights movement. The icon comes from there and we got permission from them to use it. Stokely, during that time, we had been using it in the first two or three papers. He was over at Eldridge's house studio apartment where we were working out of after we moved it from his lawyer's house. He got his own apartment. Huey and Bobby came over one day and said, "Well, we have such respect for Stokely and SNCC and they knew they were in Lowndes County." They wanted to get official permission to continue using the Panther symbol. He said he got that permission for us. Said, "Yeah, go ahead. No problem." They just had me refine it, reinterpret, redesign it.

Now, Amiri Baraka, he was more culturally involved in the movement at that time but had a good relationship. Ed Bullins, all of them did a whole fundraiser for the Black Panther Party because when we went to Sacramento and got arrested, they put on a whole fundraiser around that issue.

Transformation and Purpose

Hugh Leeman: You're a transformative figure considering you growing up, you mentioned earlier being in and out of correctional facilities and this and that, and just what you've gone on to accomplish is very impressive. This idea of you, how does that happen? Obviously it doesn't happen overnight, but you've channeled some sort of deeper sense of self to go from a challenging time in life to becoming an inspiration to countless people, many of these people that you'll never get to meet. What do you wish more people knew about your life, activism, and artwork?

Emory Douglas: I don't try to, I just do it and put it out there. I'm not trying to say, well, people need to look at this, they need to know this or know that. That's not what happens to me. That's just not me.

SNCC and the Civil Rights Movement

Hugh Leeman: Well, you mentioned SNCC disbanding. I want to admit ignorance here. I don't know what SNCC is. Tell me more about that.

Emory Douglas: SNCC, Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. That was during the civil rights movement during the 60s. You had SNCC, which was a collective of students, all kinds, all types, different colors, different scholars, intellectuals. A lot of them also folks in the South, in the rural South. They went to work in the rural South on the marches and the protests that you saw all that went on in the South during that time. SNCC was a part of that, but SNCC was a group that had to go in the South, in the rural South, and sometimes they went into areas where other folks weren't going to organize them around voting rights and education. They were supposed to bring Malcolm to the South to do thinking. They were more progressive than maybe the others of the civil rights movement were at during that time.

They worked in the South, all throughout the South. They would give them a toothbrush, maybe $5, $10, and they had to go out and organize, find a place to stay, live, and all that. They were organizers.

Hugh Leeman: As SNCC starts to disband, what comes of the influence on the Black Panther Party? How does that impact yourselves?

Emory Douglas: We had admiration for SNCC. Stokely was all in and out during SNCC days. When H. Rap Brown took over the chairmanship after Stokely, they were all in the Bay Area. They traveled all over the country. You always saw them. When you'd go to rallies, go to, there was Nathan Hare who was the professor at San Francisco State. Dr. Nathan Hare who was also a part of that group when Muhammad Ali and they met with him to support him against going to the war in Vietnam when Jim Brown and all them were there. Dr. Nathan Hare was a part of that. He was also helping develop the ethnic studies department at San Francisco State during that time. He knew and connected a lot of folks together during that time as well.

Education and Ethnic Studies

Hugh Leeman: Something I want to come back to because you mentioned San Francisco State and the development of ethnic studies programs and that becomes a powerful foundation for so many people as a form of education, but also becomes a hot button issue today. And then adding into that, City College has been, as you've mentioned in our conversation today, very impactful on your own life. Can you talk a little bit about that role of education, perhaps even now City College free tuition education, but also the challenges being faced by ethnic studies departments in the current administration?

Emory Douglas: It was generally about self, in the context of the ethnic studies. It's people of color learning about their own historical context, the rich history. That solidarity existed there during that whole movement. During that movement in time, Stokely would be invited out there to come and do talks and stuff. That's where I met him several times in Los Angeles when I was going to events and he was down there.

Sonia Sanchez, that's where I met her because she was a professor then and she asked me to do the cover of her first poetry book called Homecoming.

Collaborations and Alliances

Hugh Leeman: The Black Panthers had a lot of collaboration with other organizations and some of what you've mentioned here as well as others. How did that collaboration take place as far as conversations and dialogue to move things into the realm of, hey, we're just having a conversation to like let's actually take action together?

Emory Douglas: You have to understand, initially when the Panther came on the scene, a lot of the progressive organizations or student organizations were interested because we had a program, Ten-Point Platform Program: What We Want, What We Believe, and quality of life issues that people could resonate with.

They would always be invited to do public speaking, particularly Eldridge, Kathleen during the early days, Bobby, Huey Newton, all that during that time. We were on the campuses. We were always on the radio, KPFA, all the time. We were part of the anti-war movement during that period. Protesters, demonstrating, the whole bit. When you go back to the early days, all that's a part of the foundation of the Black Panther Party.

The Disbanding and COINTELPRO

Hugh Leeman: The Black Panther Party ultimately begins to disband in the 1980s. What was that process like?

Emory Douglas: COINTELPRO, the intelligence program, exploited our limitations as young folks, exploited us, caused internal problems and conditions, situations, mistrust. All that became a part of it. We got documents. We didn't know what it was, but we found out it was called Counter Intelligence Program.

You got a white FBI agent named Swearingen who was in the film by Stanley Nelson that he did on the Black Panther Party where he acknowledges that they had a group within the FBI called Racial Matters where if you had to hate Blacks, you'd be a part of that group within the FBI. I got documents to show Racial Matters on them. They were the ones setting up all the misbehavior and mischief and stuff that was happening. They were behind all of it. I'd say 99%. But our limitations as young people played into it in some ways.

Hugh Leeman: What were those limitations that you referred to?

Emory Douglas: I would say just being youthful, not understanding.

FBI Infiltration and Agent Provocateurs

Hugh Leeman: A really important name here to give some context. Swearingen, part of the counter intelligence movement that leads to the disbanding of the Black Panther Party. Can you talk a bit more about Swearingen, what his role was and ultimately the impact that leads to the disbanding?

Emory Douglas: I don't know what his role was. It was the FBI, period, to destroy and discredit the Black Panther Party by any means necessary. They spent over $20 million to $30 million during that time, which is a lot of money. They had people dressed up like Panthers because they knew that we had a lot of support from the vendors and stuff who were donating to the free breakfast, the free program for school kids lunch program. Dressing up like Panthers, going in, shaking down those who were our supporters, telling them that they were demanding more and it wasn't us.

Bobby Seale had a good friend who was a businessman who came to the office with a letter forged on stationary that looked like Panther stationary, threatening him. He's shaking saying, "Bobby, why are you all doing this to me? I'm doing what I can." Bobby is trying to explain, "This is not us. This is the police. It's the FBI."

You had that beginning to happen. Infiltrate the party, agent provocateurs, to create conditions where, because we would say we would not allow the police to kick in our doors without a search warrant, that we would defend ourselves, that we had no problem if they had a search warrant they could come in. We had no problem about that, but we just wouldn't let them come into our house and kick our doors in.

They exploited that because when they did that at Eldridge Cleaver's house when me and Kathleen and him were organizing one evening, we came back late that evening about midnight. There was a knock on the door. He asked who it was. In San Francisco, he asked who it was. They said it's the San Francisco police. He said, "Do you have a warrant?" They said no. He said, "Well, you're going to have to kick the door in because I'm not." They started kicking the door in. What they were looking for was illegal guns because Eldridge Cleaver was on parole and it had been in the news that Kathleen was buying a gun to defend herself, the family, because of all the threats. They were hoping they were buying illegal guns so Eldridge would have been in violation of his parole because he was still on parole. I did a cartoon around that.

I think it was two weeks later they went to Bobby Seale's house and did the same thing. It was there after that we wrote the Executive Mandate Number One, which in essence said that we would no longer allow the police to come and kick in our doors. If they had a search warrant, that was okay, but if they didn't, that we wouldn't allow them into our premises. I think in that it mentioned that they referred to the Al Capone gang back in the 40s or 30s when they dressed up like police and went across town and the gang thought they were real police and they weren't and they sprayed them. We said we don't know who you are.

Thereafter, there'd be agent provocateurs infiltrating the party, creating situations where there were these shootouts that started taking place across the country. You had misinformation campaigns, all kinds of stuff went on.

Community Programs and Support

Hugh Leeman: Because you had a lot of support. That's why you had the free breakfast lunch program in schools. It's called the Black Panther Party. You had an alternative school called Oakland Community School in the 70s. Rosa Parks came to stay with us. You had Soul Train came when we did a whole fundraiser. Soul Train came and did a whole, the guy who was head of Soul Train came out and donated $1,000 at that time.

Emory Douglas: We used to have Frankie Beverly, Cashier, all them and John Lee Hooker. All of them.

Hugh Leeman: I didn't realize Rosa Parks came out.

Emory Douglas: Yeah, she stayed for a couple of weeks. It's documented. There's photos with her and Erica Huggins who was the principal of the school.

Hugh Leeman: What was Rosa Parks' role? Was she speaking to the children? What was she doing?

Emory Douglas: She was at the school just there, showing around, being around the kids for the time that she was there. You see, the party was not just everybody in one room. We had people who worked at the school who managed that. There were people who had an alternative clinic. People had other responsibilities who worked at our street health clinics, who were out doing selling papers, donations, other stuff, doing community work or whatever it was. It wasn't like just everybody in one room.

J. Edgar Hoover and the Breakfast Program

Hugh Leeman: The first time I ever learned about the Black Panther Party was through the breakfast program. And that's what they said. J. Edgar Hoover said the breakfast program was, publicly, number one, a threat to the internal security of the United States government.

Emory Douglas: That's what J. Edgar Hoover said.

Hugh Leeman: Hoover is the head of the FBI and he's a part of the infiltration program to disband the Black Panther Party. What was the fear of the Black Panther Party in the breakfast program for feeding kids?

Emory Douglas: You have to understand, Blacks were never able to be outspoken. You still had to, you were still dealing with that colonized slave mentality, slave owner mentality, what you're dealing with. You were just supposed to stay in your place. Right when we initially went on the patrols to patrol the community against the police abuse, which was the urgency to do at that time because it was Point Number Seven of the Ten-Point Program: We want to immediately end the police brutality and murder of Black people. There were a lot of rebellions and stuff which took place in the 60s, over 300 rebellions, some big, some small, a lot of Blacks being murdered and always being justified.

When Huey and them started, that's what they started around, was Point Number Seven and patrolling the community. What happened is that they couldn't deal with that because Huey and them knew the law. This is not interfering with the arrest, was staying a legal distance away, explaining to the young people who were being arrested they had rights. All they could do if they wanted to was get a name and address or take the Fifth and don't say anything. They would tell them that. You're going to bail them out of jail if they could and they would do that. They were showing the community at the same time. People would see this and they were educating the community around those issues. They didn't like that because the Constitution was never meant for Black folks. We weren't made. We weren't in line with the Constitution.

Discovering COINTELPRO

Hugh Leeman: This idea of rights that oftentimes get taken for granted or overlooked by people who aren't of color, that haven't had your background. You have this incredible angle on this and experience with this. The Black Panther Party becomes so important for communities that have historically been oppressed. Now what we know in hindsight when the FBI starts looking into how to disband this and then infiltrating with agent provocateurs, as you say, how long was it until, when did you all start to find out, hey, this is what's going on, the FBI?

Emory Douglas: You knew something was going on after a while. You knew but didn't know what it was. Then you had just the separations, the splits, and all that stuff started happening. You knew it was something. You didn't know what it was called until COINTELPRO.

Transforming Minds

Hugh Leeman: You mentioned a conversation earlier was very interesting. Huey goes to see someone and they say, "Hey, I'm doing all that I can." Bobby Seale, that's Bobby, Bobby Seale. Thank you for the correction there. They came to our headquarters, the guy came to the headquarters there, Black Panther headquarters we had at the time. That seems like that would be incredibly challenging psychologically where there's this, and I suppose that's the point of it, but to create this sense that you guys were starting to do things to tear people apart, which wasn't the case.

Emory Douglas: We were doing things. We were changing the mindsets of people. You have to understand, that's what the issue was for the younger generation under 40 years old. You had 50 to 60% of them beginning to look at what we were doing. You had people who disagreed with us, what we were about, but wanted to set up breakfast programs, to do alternative schools. You see what I'm saying? Or demanding the free lunch program. You see? We, it wasn't about them being the Panthers, but they were inspired by and beginning to implement those programs, transforming thinking, the mindset. That was the power of the Black Panther Party in many ways.

Education as a Common Thread

Hugh Leeman: So much of what you're sharing with me today during our conversation seems like a common thread is education. You mentioned ethnic studies programs at San Francisco State. You mentioned the idea of City College and how much that connected you to the resources, ideas, people. And then here, probably the biggest impact is what you're mentioning now, that the fear of the FBI was that you were changing people's minds.

Emory Douglas: That was acknowledged. It's acknowledged in Stanley Nelson's film called Vanguard of the Revolution. It's out there online now. He's an award-winning documentary maker and you can see it online where he mixes that. Where he got a thing in there where he's talking to the FBI and the FBI had, one went up and talked to one of the kids and the little kid said, "Get your ass, you pig," or something like that to say he knew they had lost them.

They even started a football game between the San Francisco Police Department and the Oakland Police Department because of the psychological impact of the symbols of the pig and being bad behavior in the context of how we defined it. They called it the Pig Bowl, trying to change the image. It went on for about a couple of years or more and they had it disbanded because nobody was going for it.

That shows you the impact that the Panthers were having in that way, how we were involved with the mainstream civil rights movements in that context. We had a lot of their support in relationship to, because Dr. King had called Bobby Seale about a month or so before he was assassinated because he was going to start another campaign, Poor People's Campaign, and he wanted the Panthers to be a part of that campaign.

We had, Ron Dellums, who was the congressman, who was a local mayor, we knew him when he was a state assemblyman. He was supportive of us. When Huey got shot, when the police got killed, a bad actor police in Oakland, we used to hold, we began to start the Free Huey movement which Eldridge was a very high part of that, who was organizing up in Berkeley and other areas and the district by the liberals and progressives all up in those hills and areas over there in Berkeley, California by the UC Berkeley and around that area. Ron Dellums saw those programs and he saw how progressive that district was because it looked like sometimes when you run into Oakland, you think you're in Oakland but you're in Berkeley when you run into those various districts. He said how progressive that district was and he ran in that district called District 7. That's how he became the congressman over 40 years.

Barbara Lee, when she went to Mills College, she worked with the Panthers as a student at Mills College. All the way back then. Ruth Bedford, who was a well-known dancer who danced with Dorothy Dandridge back in the day, when we used to be working out the paper on Eldridge Cleaver's studio apartment, Bobby knew her and brought her over with her partner friend named Cyril to see what we were doing and what we were trying to achieve. This was the early days and the discussion came up. They were talking about the different programs like the breakfast program trying to start them and all those. She said, "Well, we might be able to have one out of my minister's church." Sure enough, he agreed to it. It was in West Oakland on 27th in West Oakland. His name was, he was a Black minister, Presbyterian, named Father Earl Neil. That's where we had one of our first breakfast programs out of that church there during that time. Dr. Earl Neil went on to work with Desmond Tutu for many years after.

We had, Marlon Brando, when Lil Bobby Hutton, the first Panther was murdered, he came and stayed with us two weeks. That could have been his family, his brother, his sister, Marlon Brando. Yes, documented. Just Google it. Marlon Brando Black Panther. You'll see it.

Legacy and Reflection

Hugh Leeman: Well, everything you've mentioned here, to kind of pull things full circle in our conversation, you very poignantly noted that, hey, this wasn't all taking place in one house. This is taking place through conversations, through relationships, and chapters and branches as the Black Panther Party evolved. You look back today with 30-some years of hindsight. What are the parts that you long for the most and miss?

Emory Douglas: I think in regards to the achievements that we were an educational spark that we were laying a foundation for, whether we were aware of it or not. We were aware of it to a degree, but the impact that it had in regards to the quality of life, historically educating to liberate, overcoming decolonization of the mind, imagination, all those things.

Maya Angelou, we got pictures of her when she used to come to the school, talk with the kids in the classroom. That shows you the broad scope of the context. When you have that kind of impact, we're putting it in our papers. We're talking about it in the whole bit in a way that ain't being talked about in other papers. People are coming to us wanting to know who they should vote for on issues. You're transforming society's thinking.

Hugh Leeman: That state of transformation that you're talking about, I think it could easily be overlooked, but it's so powerful that ultimately, as you've known and documented, it gets the FBI involved. It creates a sense of fear.

Emory Douglas: Erik Erikson, the scholar. Huey used to have, you got doctors, whole books where him and Erik Erikson had intellectual discussions, debates, and what have you.

Final Thoughts on Legacy

Hugh Leeman: Emory, with everything you've shared today, you are a living historian. You're a living archive in many ways. If we go on that idea of being a living archive to kind of close us out here, what is the legacy of the Black Panther Party and what is it that you would like youth to feel inspired by on this past that you've lived and experienced?

Emory Douglas: Well, legacy, laying the foundation for people to be inspired by, to be involved, but not necessarily to duplicate, to be inspired by and to continue in the context of now.

Hugh Leeman: Emory Douglas, thank you very much.

Emory Douglas: You're quite welcome. Thank you.