Art of Manga, de Young Museum

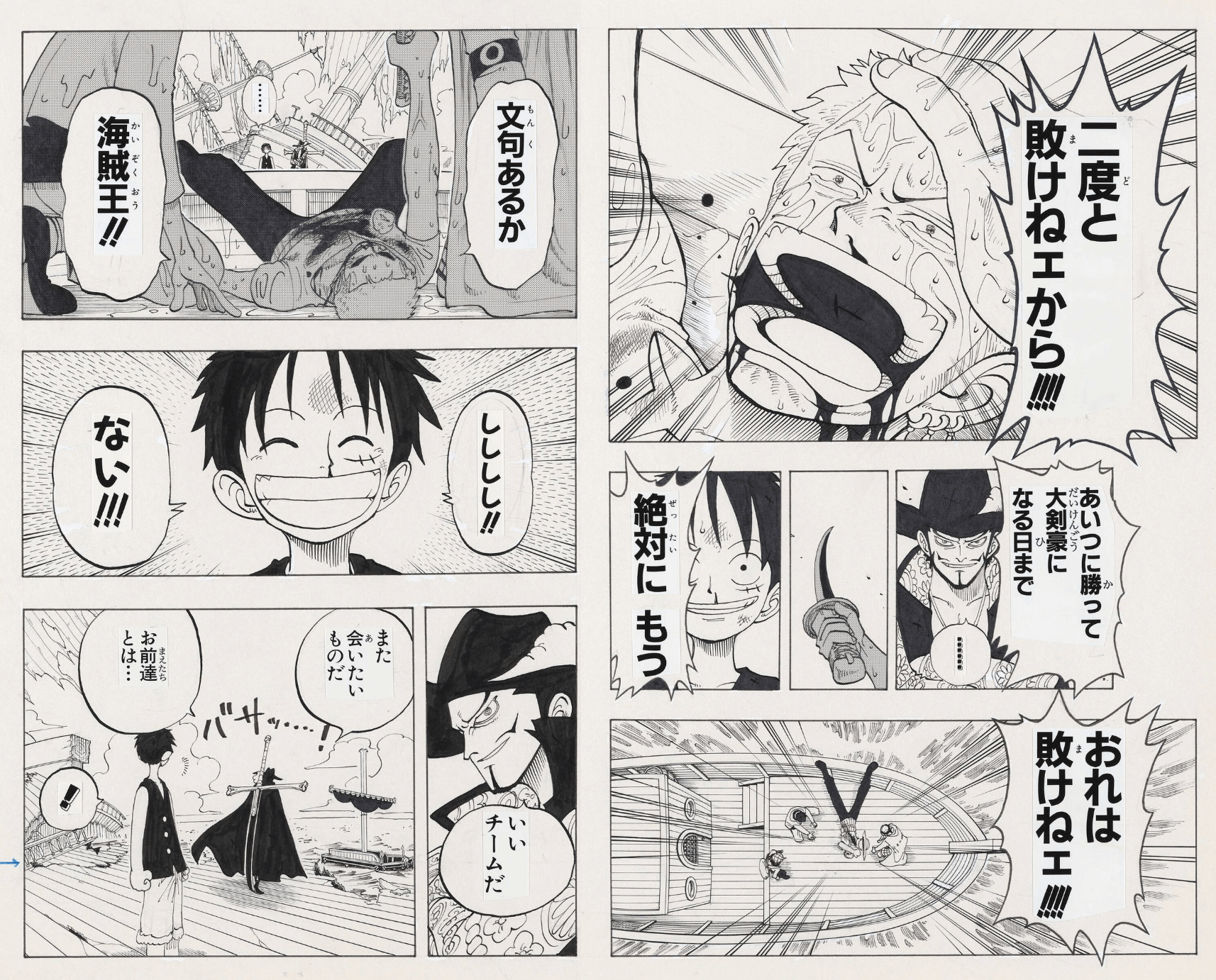

(L) Oda Eiichiro(尾田栄一郎) (born 1975), Shueisha Inc. (publisher), ONE PIECE, 1997-. Hand drawing (Ri), pen on paper, 14.33 x 10.12 in.

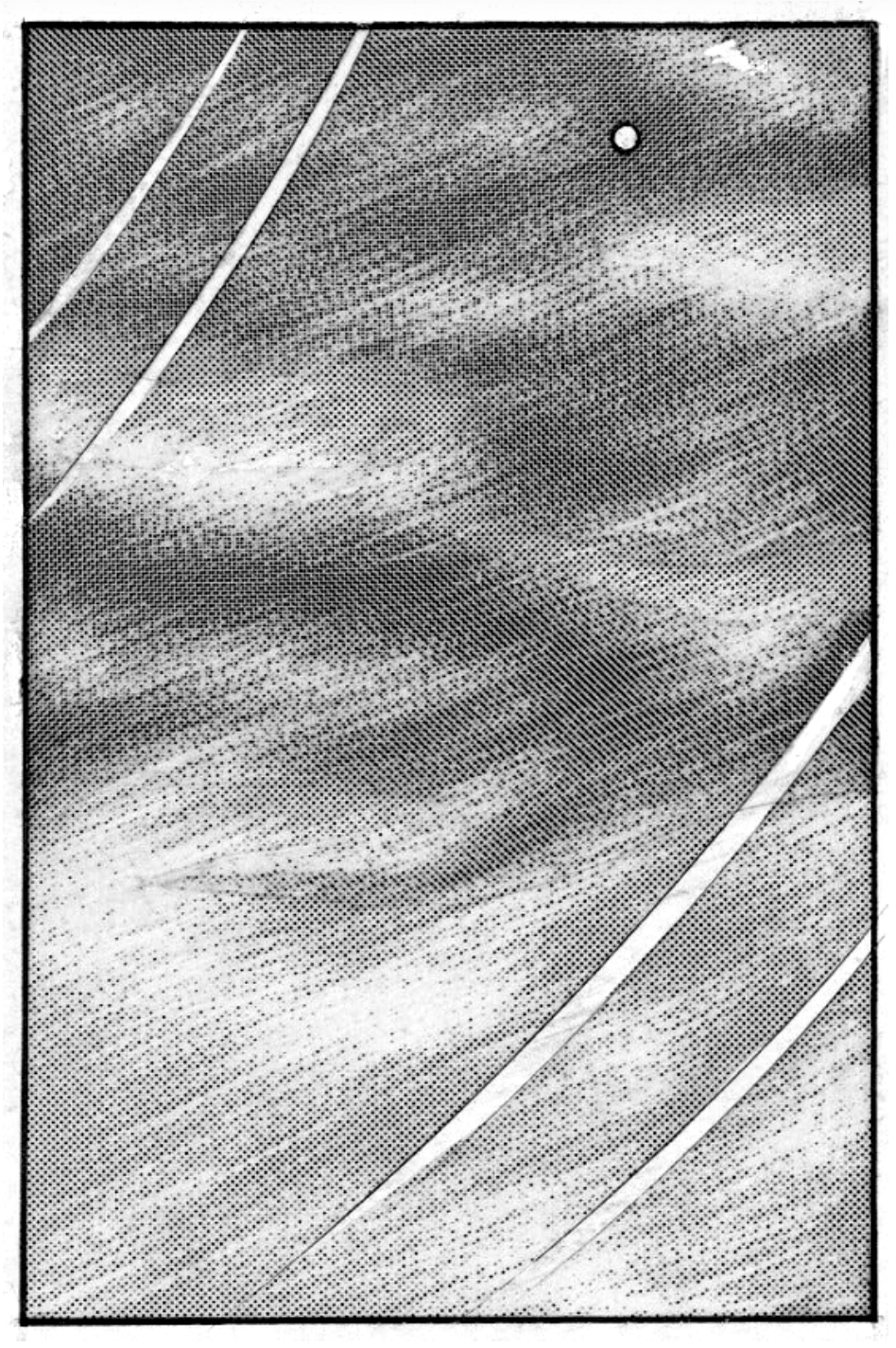

(R) Tanaami Keiichi (田名網敬一)(1936-2024), TANAAMI!! AKATSUKA!! / Revolver 2 (Looking in the Mirror)

(TANAAMI!! AKATSUKA!! / Revolver 2「鏡を見ている」).Print, print on paper (gravure), 42.6 x 29.69 in.

The Lines That Carry the World: Art of Manga

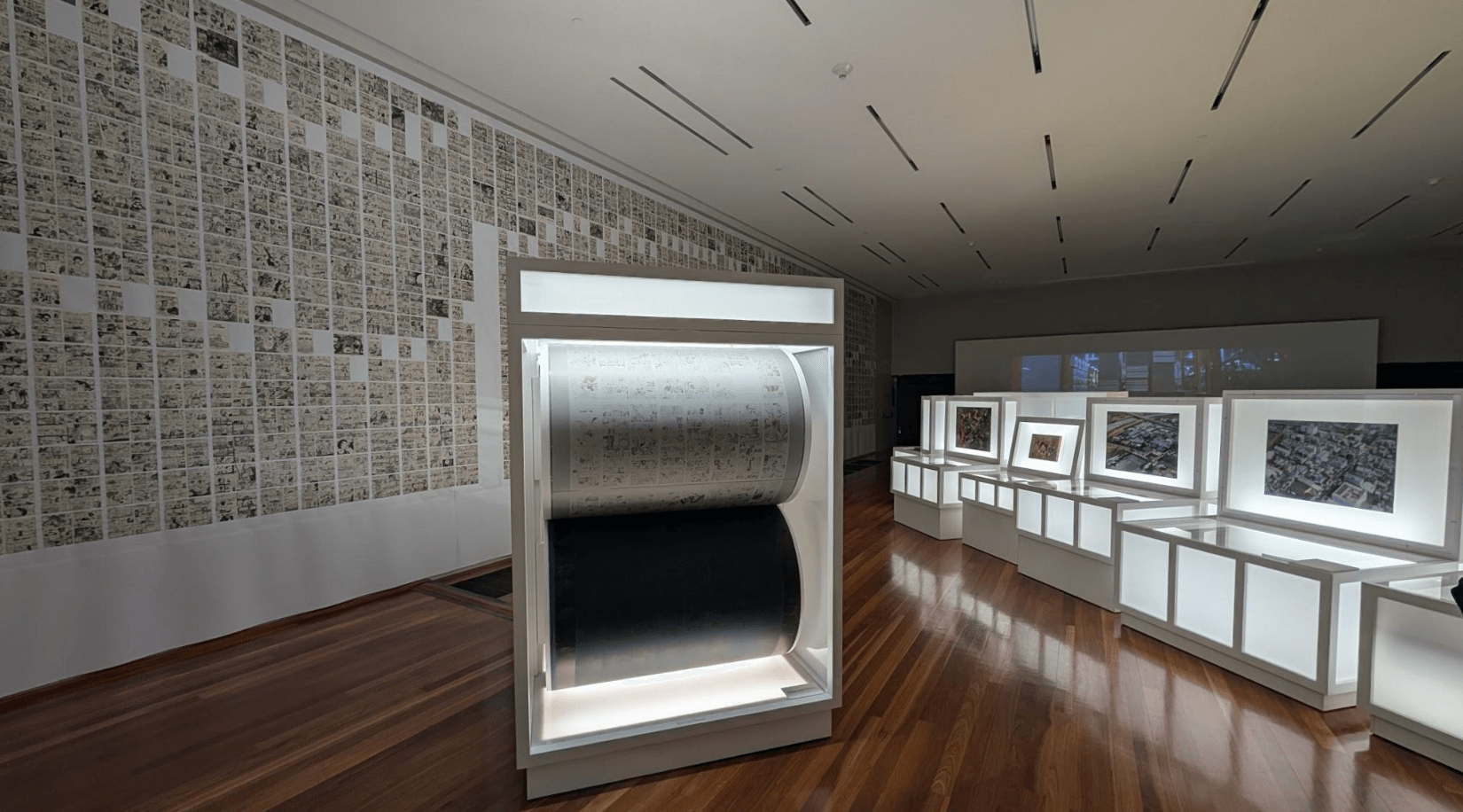

The most impactful moment in Art of Manga at the de Young Museum is not a drawing at all: The show kicks off with a room devoted to the industrial process that carries manga from a single artist's line into the world.

At a moment when museums often treat graphic narrative as something that arrives already complete, framed, and collectible, this exhibition foregrounds the fact that manga is a system of circulation. Ink, paper, labor, serialization, and mass reproduction are central to manga’s cultural force.

How Manga is Made: ONE PIECE ONLY is a prelude to the separately ticketed show. Shown for the first time in the United States, the installation traces the journey of a single sheet of paper from the creative hand of Oda Eiichiro, creator of the best-selling manga and comic series in history, through editorial processes and on to the printing presses and shipping pallets that transform it into millions of copies. The Piazzoni Murals Room transformed into a stylized print shop complete with offset plates, an epically wide-screen factory tour symphony video, treasure-box displays, and the full matrix of One Piece, Chapter 1000. These elements make clear how a weekly chapter is the result of a vast logistical choreography established to meet the anticipation of millions of readers. With One Piece now exceeding 1,151 serialized episodes and 111 collected volumes, the exhibition frames the printing press not as background machinery but as a co-author of the work’s global presence, vast and intimate all at once.

That framing matters because manga is fundamentally structured around time pressure. Many series are written and drawn in weekly chapters, a rhythm that demands relentless production. Artists do not work toward a distant, polished object but toward an immovable deadline that arrives every seven days. This cadence shapes everything from line economy and chromatic rigor to compositional clarity. The aesthetic emerges from creative vision and narrative passion as much as from repetition, speed, and scale. Circulation is a driving force of creativity, and the weekly production reads as an amazing performance, in sync and solidarity with the reader's workweek.

Rather than diluting this argument through an encyclopedic overview, Art of Manga leverages the power of about 600 original manga drawings to sustain the viewer's engagement with just a few individual artists rather than the entire genre. Dedicated sections focus on Araki Hirohiko, Oda Eiichiro, Tagame Gengoroh, Takahashi Rumiko, Taniguchi Jirō, Yamashita Kazumi, Yamazaki Mari, and Yoshinaga Fumi, while works by Akatsuka Fujio and Chiba Tetsuya set the historical tone at the beginning. The exhibition concludes with Shueisha’s Manga-Art Heritage initiative, featuring work by Tanaami Keiichi, which flips manga into museum art.

These extended presentations allow visitors to read manga spatially and temporally rather than as isolated images. Worlds unfold panel by panel. Styles declare themselves through accumulation rather than flourish. One begins to see how Araki’s charged formalism, Takahashi’s iconic clarity, Taniguchi’s quiet realism, Tagame’s compositional rigor, Yamazaki’s historical satire, Yamashita’s long-form narrative ambition, and Yoshinaga’s social complexity each represent distinct solutions to the same problem: how to create narrative time, space, and depth despite the deadlines.

This attention to labor and process makes one curatorial omission especially conspicuous. The dry-transfer technique, historically central to manga production, is not discussed or featured at all, although it is present in every hand-drawn panel. To create gradients and shading, manga artists often fill the ink-drawn form with textures they rub off of pre-printed, frosted plastic sheets. These textures, often modulated with erased portions or overlays, make the artwork camera-ready without a halftone step in between, and the artists directly and manually control how every tonal value appears in print. Dry transfer enables the rapid creation of volumetric nuance, light and shadow, and complex patterns such as water and sky. It becomes an integral part of the clean visual grammar of manga. Even at the level of the drawing board, manga rises from the conflict between humanity and mechanization, and therein finds its depth. Dry transfer occupies a crucial space between hand and machine, exactly the kind of hybrid technique that belongs in an exhibition so attuned to reproduction and circulation. Its absence leaves a gap.

That gap widens in the museum store. Visitors leave visibly energized, despite having spent 2.5x the time allotted to a typical museum exhibit, not only wanting to read more manga but also eager to sketch some fan art, or who knows, start another series that runs for decades. The exhibition succeeds in inspiring a sense of participation, yet no dry transfer materials are to be found. This feels like a missed pedagogical opportunity.

Manga thrives on dynamic relations between reader and maker, professional and fans. Dry transfer is a gateway technique that makes participation possible under real-world constraints of speed and access. While the exhibition’s printing press celebrates circulation at scale, the absence of dry transfer, paper and ink quietly reins that circulation in.

Elsewhere, the de Young embraces circulation beautifully. Cosplay, the practice of dressing up as a manga character, is integrated into the exhibition’s logic. Visitors are invited to attend in costume on select dates, use an on-site “Cos-closet” to store props, and even receive a discount with the "DYCOSPLAY" cosplay code. This matters. Manga’s circulation has always been social as much as material, passing through bodies, performances, and gradient identities. Allowing manga to move through the museum in this way affirms it as a living practice rather than a sealed archive.

Art of Manga offers one of the most thoughtful, true-to-the-medium, museum treatments of manga yet seen in North America. By foregrounding production, serialization, and circulation, it understands manga not simply as an image style but as a cultural technology shaped by deadlines, presses, and communities. Manga moves because it was built to move, week by week, chapter by chapter, from hand to hand: lines over screens.