L. Song Wu, Feast, Johansson Projects

By Hugh Leeman

L. Song Wu's Feast at Johansson Projects is served as a postmodern synthesis of internet Mukbang culture's spectacle of glutinous consumption, 17th-century Dutch Still Life, and fantastical anime aesthetics. The Asian American artist's works are equally humorous and confrontational, referencing diaspora, academic discourse, and childhood memory. Through saturated colors in oil paintings, visually textured colored pencil drawings, and ceramic sculpture, symbols of digital subculture are harvested from social media's seemingly infinite opportunities for the consumer to be consumed.

Wu's overflowing dinner tables situate the viewer as if we are the camera in an influencer's socially empty experience. Her flat planes of saturated color recall Alex Katz and Barkley L. Hendricks; the paintings' heightened chroma amplify the scene's artificiality. The artist says the exhibition is structured around titles that echo the courses of an Italian meal: primo, secondo, formaggio, and dolce, "like a love letter" to her Italian partner. However, Feast's central theme centers on Mukbang culture: online videos featuring content creators known as Mukbangers who gain followers by consuming prodigious quantities of food.

Mukbang, which began in South Korea as a way to virtually eat together, has shifted into a spectacle competition of follower counts. What was once a virtual space for eating together has become a globalized, solitary affair in 21st-century digital-mediated realms. Wu, born in 2001 of a digitally native generation, tells me of Mukbang culture, "It has shaped my relationship to my body and how I see myself. I was interested in the voyeuristic aspect and the aspect of the Asian women who participate in it. You only see them from their busts up. I did Mukbang paintings before the ones in this show. In Feast, I wanted to interrogate it more. It heightens the surrealness of life around me. It becomes more apparent that everything online is a lot of smoke and mirrors."

Wu connects today's voracious appetite for digital consumption with art history through Dutch Pronkstilleven, 17th-century still life that focuses on copious quantities of food set on lavish tables. Wu's feasts like Pronkstilleven are choreographed scenes, leaving viewers to sift through objects of desire symbolizing globalization while provoking reflection on excess, impulse, and the pleasure of looking.

(L)Budino (Dolce), oil on canvas, 16” x 16”, (R) Leaning Burger, colored pencil on paper, 12” x 9”

The artist grounds Feast in contemporary academic discourse on race, gender, and class status as they relate to eating. Wu tells me that scholar Kyla Wazana Tompkins's book Racial Indigestion has inspired her, causing her to consider "How you consume and what you consume are related to how we are perceived. We are making bodies consumable bodies. It is a performance around the body and race." Beyond Tompkins, the artist notes, scholar Anne Anlin Cheng also inspires her: "She inspired me with ideas in her book Ornamentalism on how Asiatic femininity is experienced in Western imagination as ornaments."

In Feast, Wu's subjects become ornamental vessels allowing for Mukbang's vicarious, calorie-free consumption; yet, stepping out of the smoke and mirrors, we see that the Asian female subjects in her paintings are the object. The usual act of seeing the food consumed by an ever-slender internet star translated into paint adds depth to their digital context, in which they are less a person and more an objectified persona in the algorithm of internet life.

In previous exhibitions, Wu confrontationally situated viewers, on the ground beneath the aggressive shovel of a topless woman or perhaps as being watched through the mini blinds by a bare-breasted female, yet in Feast's most commanding pieces, the viewer sits across the dinner table from young women who sitting tall, skin tones as monochromatic as the backgrounds, leave an aesthetic contrast between the food's realism and its adjacent consumer. The sitters' overly energetic eyes fix on the viewer as their unnaturally large smiles feign for our attention.

In Sweet Treats (Dolce), a mountain of desserts appears to compress Wayne Thiebaud's oeuvre with a 1970s-saturated cookbook photo, pulling us past the female figure's bust towards her overly enthusiastic eyes, loaded with faux pleasure. Returning our gaze, the sitter is backdropped by an Italian countryside; its atmospherically shaded sky appears painted by the brush of an anime artist. Yet despite the fabulously painted realism of the food, nothing, it seems, in her world is real.

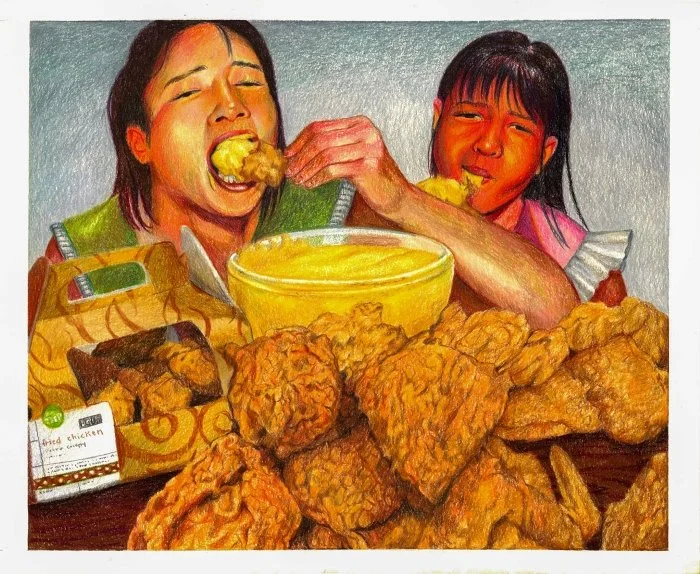

A similar composition in Costco Chicken (Secondo) situates the viewer in the direct gaze of the Mukbanger backdropped by a monochromatic wall that collapses depth, heightening the confrontation. The chicken is not just any chicken; it's Costco chicken. The piece speaks to the artist's inspiration from Tompkins's writing on race, social class, and its connection to the food one consumes, according to Numerator, a market research firm: "Compared to the average American consumer, Costco shoppers are 81% more likely to be Asian." Wu says of being Asian American, "I was lucky that I could go back to China on a semi-frequent basis. I've gotten to go back, and it's a different world for me from the suburb I grew up in, Tampa, Florida. It's become very important for me to understand contemporary Chinese culture. All of my family is still there." The bulk brands' cost efficiency contrasts with the Mukbanger's pinky finger etiquette, historically a status symbol of the elite, later emulated by the working class.

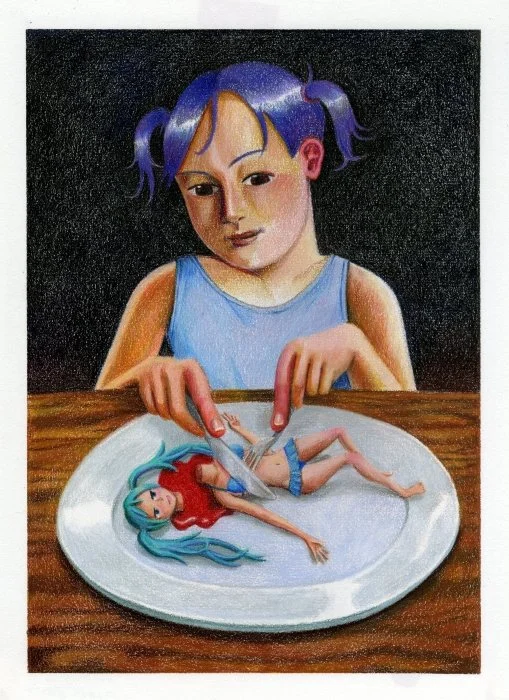

Wu reveals the often unseen influence of different worlds in Local Perversion. The twenty-something sitter in the oil paintings has been exchanged for an adolescent rendered in colored pencil who, left alone to eat, is readying to consume a thin, bikini-clad Barbie doll, suggesting an early infusion of Western beauty standards and a melding of worlds in Wu's life and paintings.

L. Song Wu's Feast entices, confronts, and questions our world with a dynamic mix of emotions as if an id for the digital age from the supposed safety of screens, leaving the consumer stuffed with food and surrounded by online followers, yet empty and isolated. The artist says of her inspiration, "I found Mukbang so fascinating. There are so many reasons why people engage, like the voyeuristic aspect and living through the Mukbanger's experience; there is an erotic aspect to it. It's about consuming the person more than the food. It's erotic to watch; there is a social aspect that makes it popular. But people in the West don't eat with one another anymore. We eat alone at our desk, we eat fast."

Wu speaks with a vulnerable honesty, her paintings with confrontational humor, all of which allow us to see society, the online gluttonous subculture, and the consumers of screen culture as the consumed; her artwork asks us: with all this consumption, does anyone ever feel full?