Casual Time, Altman Siegel, San Francisco

The Devil is in the Details

By: John Zarobell

Figurative painting, as the title suggests, usually includes images of people, but it is also half of the painting dichotomy, Abstract/Figurative, suggesting that any painting that is not abstract is, by nature, figurative. But figurative artists, at least since Velázquez, have been experimenting with abstraction, so it is also not accurate to say that these terms are mutually exclusive. Figurative painting is an elastic concept, and nowhere is this more visible than in “Casual Time”, an exhibition at Altman Siegel Gallery that features five figurative painters from Latin America and Asia, some showing for the first time in the US. The scope of the show is wide, but it is focused on the idea of representing the materiality of the world through a very focused practice that concentrates on specific details and universalizes this visual experience into a perceptual domain.

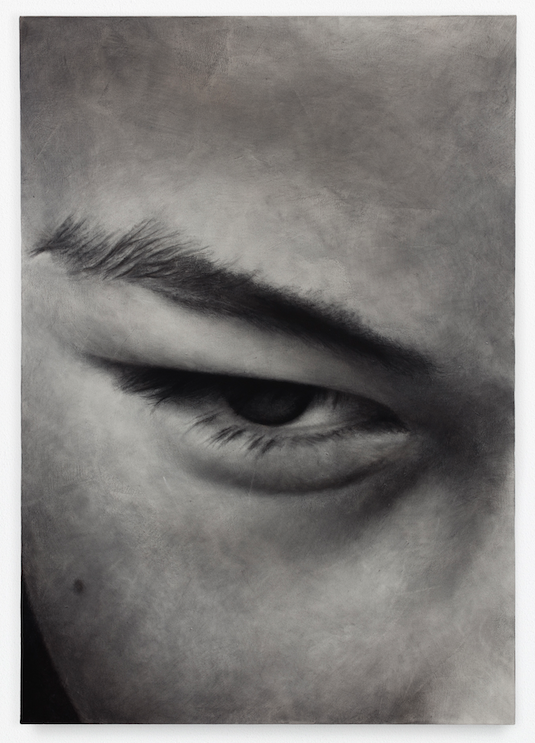

This exhibition is striking, for various reasons, but the most salient is the fact that, in an era of constant distractions and endless multitasking, it forces viewers to look carefully at one thing, for a duration, and the works on view disclose subtle information through the process. We don’t have to ask if what we are seeing is real or some ideological projection. We see the painting as an object that represents a specific visual phenomenon produced by looking and, in the case of two of the works on view, what we see is an eye looking back at us (Rodolfo Abularach’s Artio and Alexandre Zhu’s Two-Speed). In these works, we see ourselves looking, as the very subject of the paintings we see—that is just the beginning of the complexity this exhibition presents.

While the gallery’s press release suggests there is a connection between specificity and universality at play in these works, I see another dynamic also emerging: the relationship of the materiality of painting and the materiality of the world. Due to painting’s history as a medium that produces illusions, these are thought to be fundamentally incommensurate. As a painter, one loses the idea of the subject in the visual experience of it; it is more effective to paint what you see than what you think you see. As viewers, we all want to know what we are looking at. And so, as with Magritte’s “This is not a pipe”, painting does not answer this question so much as deflect it. Magritte’s “things” were rendered flatly, almost matter-of-factly, but not the works in this show. Each of these artists is seeking to find the message of painting through the process of making it. These processes are varied but conceptually coherent. The paradox this show exposes is that the more carefully you look at something, the more it disappears.

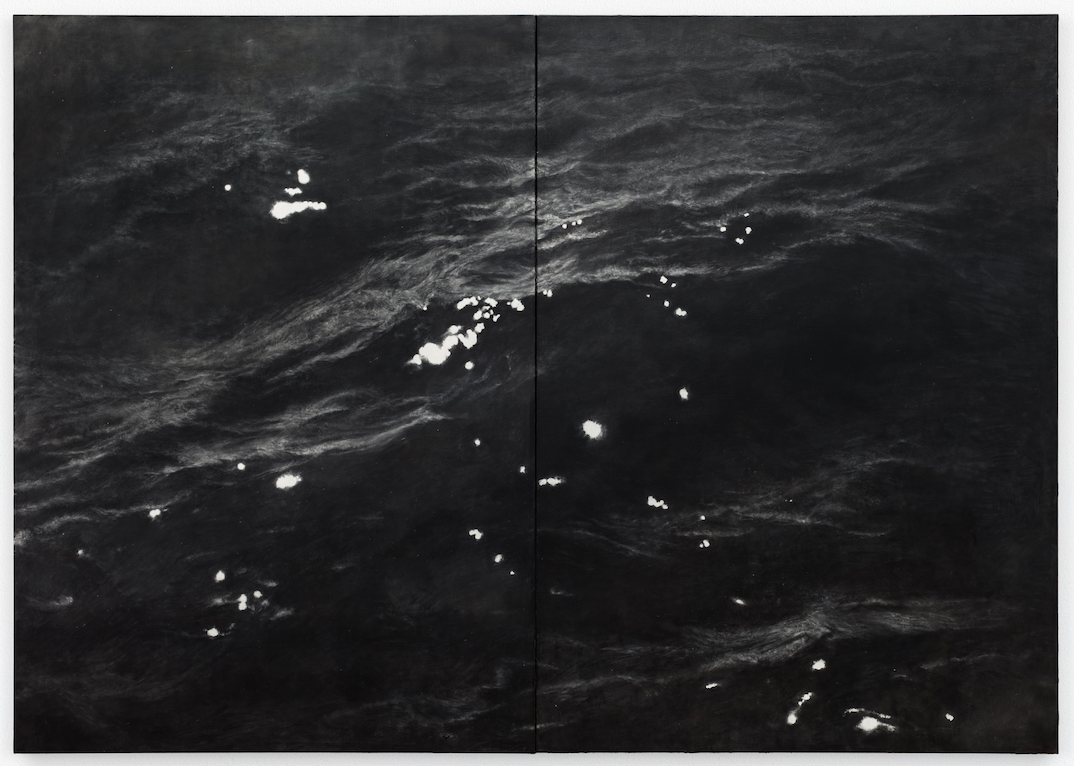

Take Alexander Zhu’s Hadal (2025), the first work one encounters on entering the gallery. It is a larger-than-life diptych representing a fragment of ocean through the medium of charcoal on canvas. What the viewer sees are reflections of light and the careful modulation of tone that suggests the architecture of waves. What looks like a painting is actually a drawing, and it represents what a slice of ocean would look like at one moment in time, as if caught by a photograph. There is duplicity here—a painting that looks like a photograph but is actually a drawing—but to call this work illusionistic misses the mark. One encounters a uniquely crafted visual experience that appears familiar, yet the more one examines it, the more the conventions that undergird it seem to fall apart. If it captures a moment in time, why does it take so long for a viewer to figure out what she is looking at? It is a large and highly-detailed drawing with bravura technique, alluring and fascinating as an object in its own right.

Victoria Gitman’s On Display (2010) is the smallest painting in the show, and it depicts what appears to be a beaded bag. The craftsmanship of the object depicted is so precise and impressive, yet it is doubled by the craftsmanship of the painter who depicted it in all its visual wonder. It depicts a perfectly square object made of tiny beads in two colors, rendering an organic pattern across its surface. The meticulous painting technique required for us to look at this painting and mistake it for a photograph is another bravura technical accomplishment. The concentration required to render more than a thousand beads photo-realistically on a surface smaller than 8 x 10 inches boggles the mind. Once again, there is duplicity here—is it a photograph? My G-d, that’s a painting! Issues like composition, color, and pictorial structure, which art historians employ to analyze paintings, don’t seem relevant here. It is flat and colorless and absolutely hypnotic because one gets lost in the magnificent character of the painting as an object, one which represents another object but which discloses the attention the artist devoted to seeing this thing. Like an echo, we get caught in the same process of visual discernment, but with a picture.

(L) Alexandre Zhu, Please turn off all electronic devices, 2025, Charcoal on canvas, 39 3/8 x 27 1/2 in (R) detail

But there is something more than detail, more than exquisite craft, at work in these pieces. In their absolute attentiveness to the visual character of the world we inhabit, these pictures illuminate something beyond the visual, something that a viewer cannot see but only sense. Freud used the idea of the uncanny to suggest the uneasy sensation of seeing a familiar object in an unfamiliar situation—a museum object rendered as a painting, in this case—that causes anxiety. That applies here because the closer we look at these detailed representations of our shared world, the more it seems like there is more there than meets the eye. The more in this case is not a political or social message hidden behind the surfaces, but a power that such visual images seem to be able to conjure, perhaps because the means and the ends so closely align. Here is the devil in the details, or maybe it is the Universe itself, but presented without any trappings of spirituality.

To explore this point further, it will be useful to look at Xiaochi Dong’s Twilight (2025). The materials of this piece are listed as “ink, acrylic, Akadama soil, Moroccan red clay powder on linen,” so it is also a painting/not painting. It is a painting made of earth that seeks to represent the world, or at least a visual experience of it. As we all know, twilight is a visual phenomenon, when the light of the day shifts as the sun descends below the horizon, making the world appear strange in the half-light. Twilight is a magisterial painting, larger than life at 70 7/8 x 86 5/8 inches, and there are a number of landscape elements visible, such as the small sailboat on the left or the horizon line near the top. Dong’s work is the most openly abstract of the artists on view, and layers of planes are also visible on the right-hand side of the work, which evoke the abstractions of the Cubists or the Orphism of Sonia and Robert Delaunay. There is also an aureole of light, like a blooming flower, that expands across the upper left of the painting. Are we looking at two registers of reality, like a doubly-exposed photograph? Unlike the others, this painting seems not to resolve into a single image.

This has the effect of bringing the viewer’s attention to the surface, where one encounters small piles of earth that hold the ink and acrylic materials and generate an overall texture across the painting. There seems to be another landscape unfolding here, as if the painting were a microcosm of the world, more a map than a picture, but a relief map. Yet the painting also reads as an image, producing another doubling where the character of the surface competes with the coherence of the picture. The rendering of an image with earth generates a dichotomy of surface/image that trumps abstract/figurative. In the latter, we understand painting to be pictorial in both contexts, but in Dong’s work, painting is both physical and imagistic, and the details a viewer perceives transfer our attention back and forth from matter to image. The painting comes to life not because of its visual coherence, but through the play between the visual and the physical, and this transit allows the viewer to see the world anew. The illusionistic impulse in painting is not the mechanism that holds the work together but a means to see the reality of the process, the making of the image from discrete units that both cohere into a picture and disintegrate into clusters of dust. This visual metaphor of Twilight opens and closes, like human life: ashes to image, picture to dust.