Bill Kane, Light Bodies, Themes and Projects

Everything You Know Is False

By Scott Snibbe

Bill Kane's striking abstract color-field work began, like many creative discoveries, with a problem. Hoping to enliven the walls of his Petaluma Buddhist center with portraits of great masters, he found his teacher forbidding any guru’s depiction behind the sangha's backs.

Determined to decorate this blank wall, he digitally scanned and deconstructed a traditional Tibetan Buddhist thangka painting of 12th-century Buddhist master Geshe Chekawa, then simplified and filtered it, eventually condensing it into an abstract, rectilinear composition. Pleased with the intuitive bliss the image sparked in him, he had the abstraction sewn into four vertical silk tapestries with a striking red central square evoking the interdependent field of emptiness from which all things emerge.

This seminal work, Chekawa, now hangs outside Themes and Projects Gallery at San Francisco's Minnesota Street project as the welcome to his two-month exhibition, Light Bodies. Unapologetic joy has become a hallmark of Kane's work over the fifteen years since that first experiment, adapting Buddhist devotional paintings into contemporary abstract art—first through digitally produced canvas print editions and now, in his latest works, through high-tech lenticular imagery.

Most of the current exhibition is rendered as these shimmering, shifting images that change as you approach and move around them. You may be familiar with the technology behind lenticular prints, as seen on science museum postcards featuring three-dimensional planets and frogs. But here, Bill's use of multi-perspective imaging technology serves a deeper purpose. Instead of conveying physicality, works like Lotsawa, Chopel, and Dargye evoke the shifting nature of an enlightened mind. Kane describes the common nature of evolved beings as "one actor playing different parts in a play." "It's the same essence," he says, "so I like the idea of playing them off one another."

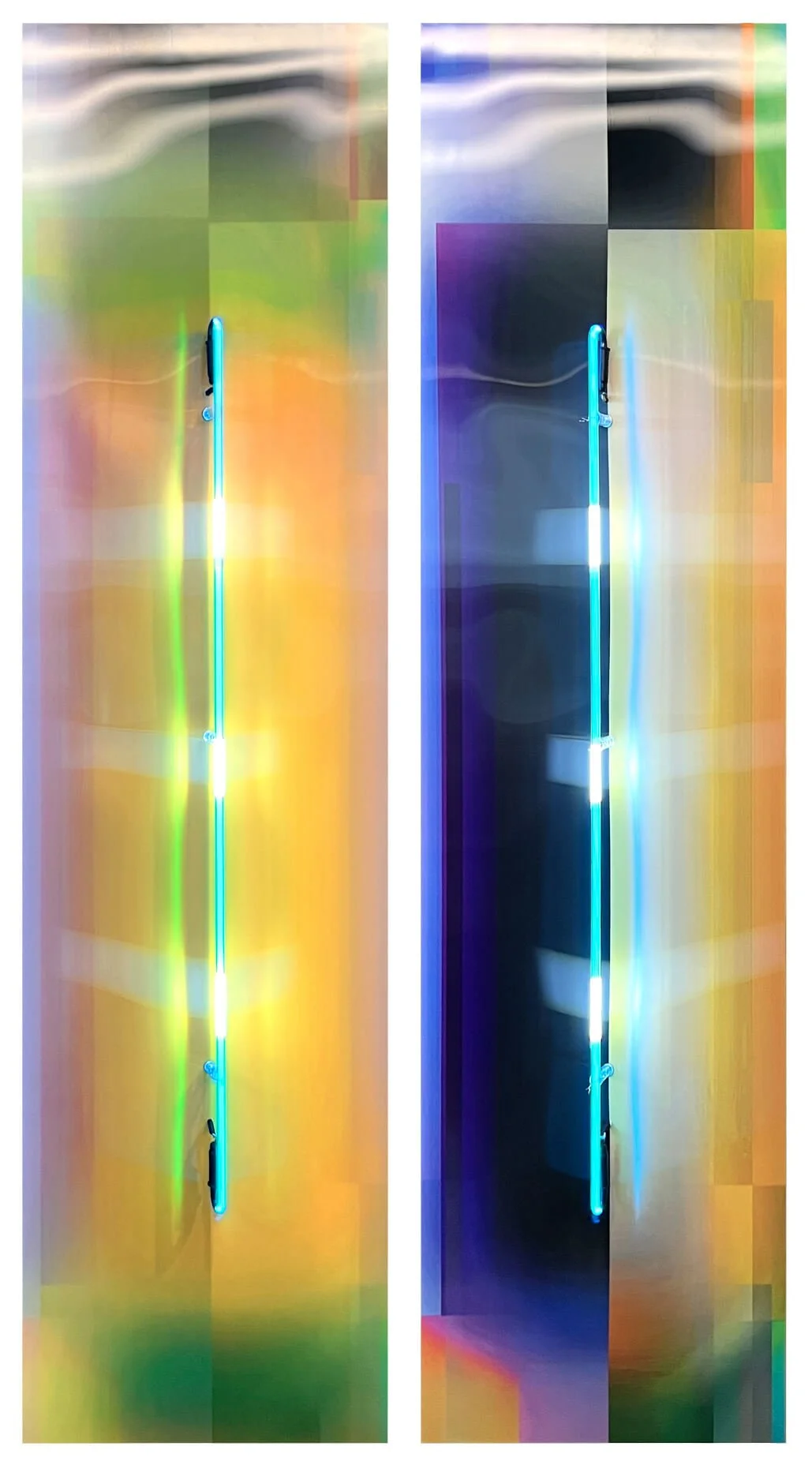

(L) Bill Kane, LenEM-93 Dargyay, Lenticular print on wooden back frame, edition of 3, 76 x 21 inches, 2025

(R) Bill Kane, LenEM-317 Lotsawa, Lenticular print on wooden back frame, edition of 3, 76 x 21 inches, 2025

The works flicker between vivid color, deep blacks, and foggy whites as you move about them, embodying the Buddhist truth of impermanence. These images are never quite the same, and can't be seen fully without the viewer also changing their own point of view.

Most of these new works of art, like Bill's earlier pigment-based works, are rendered in a striking vertical aspect ratio, more than six feet tall. They loom above viewers, forcing us to look up in postures of devotion. Their tall, rectangular presence evokes regal bodies that seem to radiate wisdom and warmth.

Proportioning the works like human bodies is fitting in images that originate as realistic depictions of enlightened bodies, distilled by Kane into their colorfield essences. When I interviewed Bill for this article, he shuffled through decks of postcard-sized test prints made to evaluate works in progress. But he admitted to an element of surprise in enlarging them, because only when magnified to life size does their energy coalesce. The successful ones inspire us to imagine the ultimate evolution of a human being, what Buddhists call a Buddha.

The body-like proportions of the wall-mounted pieces are further reinforced by a new sculptural form that Bill introduces in this show: lenticular prints, such as Shangton and Rabten, mounted on free-standing aluminum pedestals. They stand, approachable in the gallery, like wise, charismatic friends.

Sonam stands out, with a vertical neon shaft running through its center. At first, I found myself confused by this new direction. But then I learned of Kane's long history with neon that extends back to the 1980s, when he traced the accidental forms of hugely enlarged photographs of city-wall cracks with carefully kinked neon. By reincorporating this glowing medium today, the vertical neon tube evokes the subtle energy channels of the body. Tibetan Buddhists describe these channels and the winds that flow through them as crucial to developing a happy, stable mind. In most of us, these channels are knotted and blocked, but in more evolved beings, they are clear, supple, and filled with light.

Bill's work recalls several phases of Western abstract art, particularly the color field paintings of Mark Rothko. I was struck by the different emotional impact of Rothko's work when compared to Bill's. Rothko's late works convey sorrow and nihilism, while Kane's abstractions radiate joy and luminosity. Yet, when I shared this comparison with Bill, he reminded me of Rothko's earlier, more luminous, rhapsodic work, underscoring their shared talent in conveying such emotions through color.

So much does Bill rely on emotion and intuition in his work that, in his earlier photographic series, after taking a picture of an object, he would step forward to place his hand on it to feel its essence. Digging deeper, trying to get at the essence, is something Kane has pursued for most of his life—without religion—the way many of us today search for intuitive connection with forces beyond the self. Eventually, in Buddhism, he found an organized path to probing the essence of reality, which he began to practice when a Buddhist center opened just steps from his door in Petaluma.

Bill's work today is unapologetically spiritual. However, those who exhibit, admire, and collect his work don't necessarily see and experience it that way. What they do feel is the joy and aspiration embodied in these images: that even in dark times, it is possible to aspire to—and become—one's best self.

Kane told me that he appreciates Buddhism because it doesn't provide definitive answers, but instead offers profound questions that one explores through meditation and reflection. He describes the arc of his art the same way: exploring points of view in photography, bending light through glass tubes, or blurring Buddha images back into the light bodies they inhabit when they're not manifesting in the physical forms of teachers and gurus.

"Everything we know is false" is one of the teachings that Bill treasures most from his Buddhist instruction. Because we have minds, we name things; we develop strong likes and dislikes; these grow into firm feelings of right and wrong, biases, and conflicts. Our minds are out of control, hypnotized by deluded ways of seeing reality and ourselves.

Everything we know is false. Yet through the lens of ordinary perception, Kane's art reveals a world transformed from the coarse and unkind to one that is luminous, welcoming, and ecstatic.

Light Bodies , New Lenticular Works by Bill Kane Themes + Projects Gallery, San Francisco September 6 – October 25, 2025