Siana Smith

Siana Smith is a visual artist whose work explores the complexities of consumerism, personal attachment, and environmental impact through depictions of daily objects and people. Drawing on her experiences as an immigrant who arrived in the United States in the early 1990s, Siana’s art reflects a unique perspective shaped by her upbringing in post-Cultural Revolution China and her immersion in American consumer culture. This duality plays a central role in her practice, infusing her paintings with symbols of transience and tension that invite viewers to look beyond the surface allure of objects and consider their more profound social and psychological contexts.

Siana’s work has been exhibited nationally at the De Young Museum, the New York Academy of Art, the Triton Museum of Santa Clara, Southern Arkansas University. Through her art, Siana engages in conversations about consumer culture, identity, and the environment.

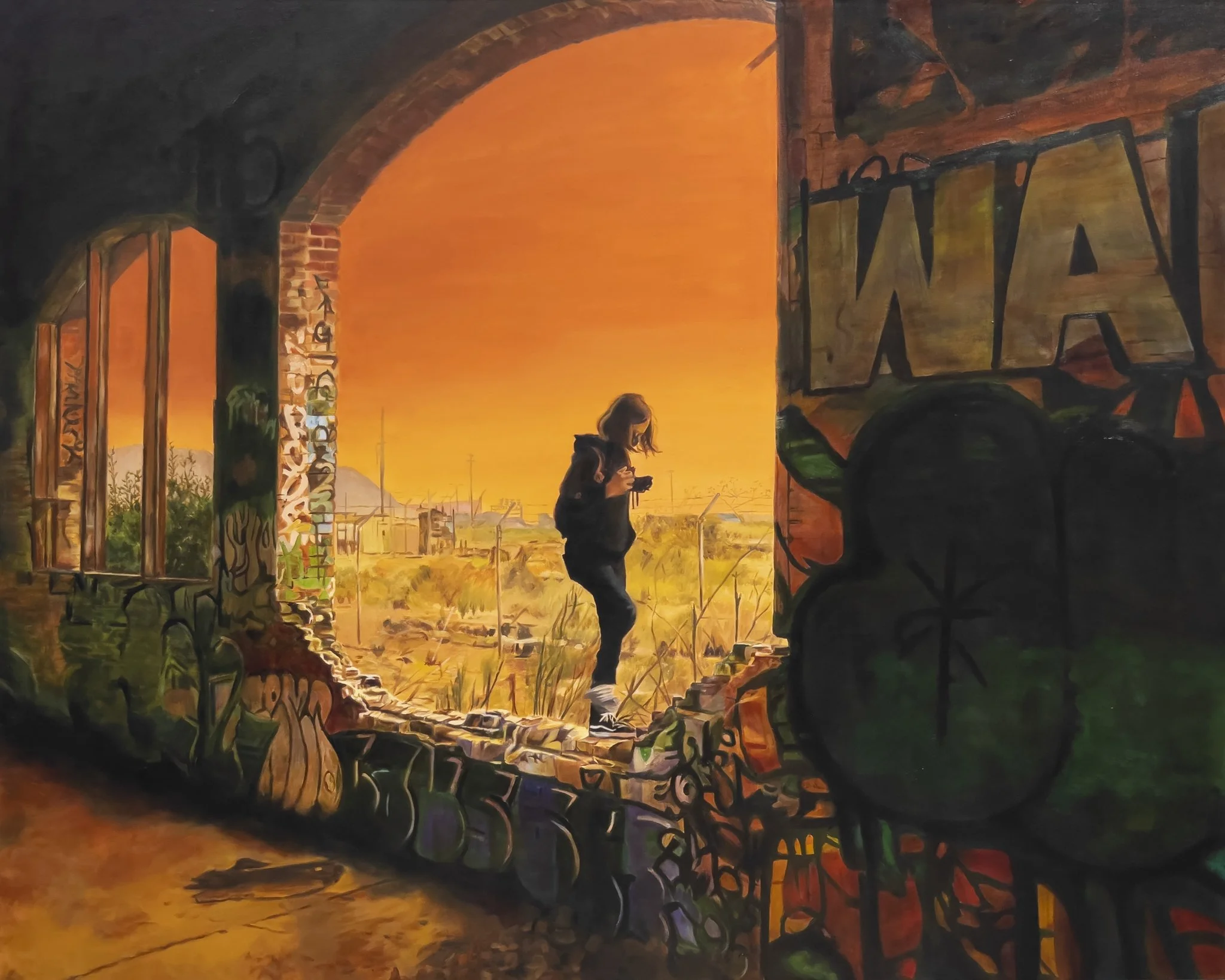

(L) Contemplate , oil on canvas, 48”X36”

Hugh Leeman: You grew up in a post-Cultural Revolution China amidst phenomenal change. What were these experiences like amidst such transformative times, and how did these experiences influence your worldview?

Siana Smith: Growing up in post–Cultural Revolution China meant living with scarcity as a daily reality. Grocery store shelves were often bare, and when they were restocked, long lines formed instantly. Food, fabric, and daily necessities were rationed by age, and it was a rare joy to eat until my tummy was full, something I most vividly remember at Spring Festival, which is my favorite holiday. Every object was saved, repaired, or repurposed. A jacket was passed down from my mom to my brother and then to me. My Dad, a professor, and my mom, a medicine researcher, like many educated people at that time, were sent to the countryside and a factory to be "reeducated". So, I was sent to my grandparents and sitters until I was old enough to go to kindergarten. Watching my parents work hard to provide for us, I absorbed values of resilience, frugality, and perseverance. These early experiences gave me valuable connections, belonging, and hardworking values, teaching me to see both the fragility and the endurance of human life, and they continue to inform how I see the world and deeply impact my art today.

HL:You arrived in the United States in the early 1990s. As an artist who is a keen observer, what were your perceptions of the United States before arriving, in comparison to the reality you observed after arriving?

(L) Crmpl I , oil on canvas, 48”X36”

SS: Before coming to the United States, I imagined it as a land of abundance, beauty, and endless opportunity. From afar, America seemed like a place where store shelves were always full, life was comfortable, and happiness was easily within reach. When I arrived in Milwaukee, WI, in the early 1990s, I saw the abundance was real: stores overflowing with goods, everybody was in a car, and I rarely saw people walking on the street. But I was also struck by the culture of disposability. Perfectly good furniture was left on the curb, utensils and napkins were used once and thrown away, and things were replaced rather than repaired. My first couch even came from the street. That sense of excess surprised me, especially after growing up in scarcity. Looking back, I think it might have subconsciously influenced my "Crmpl" series, where I painted used tissues as a way of seeing value among the waste.

Opportunities were indeed present, but I realized they required persistence, resilience, and hard work. The contrast between plenty and waste, opportunity and struggle, has stayed with me and found its way into my paintings.

HL: Growing up in China before it was open to the West, and now living in San Francisco, California, what are your early memories of art in China during your childhood, and how has living in the United States impacted your perceptions of art?

SS: Growing up in China before it opened to the West, I had little exposure to Western art. Many books were forbidden and destroyed, and cultural life was restricted. One of my earliest memories of beauty came from listening secretly with my family to classical music on a short-wave radio at night, the volume turned low so we wouldn't be overheard. There were no art classes or after-school art activities, and my first formal encounter with art was much later, in college, when I took a drawing class, which I liked.

At home, we hung three of my late grandfather's Chinese ink paintings.

After moving to the United States, I was amazed at how art seemed to be everywhere: galleries, museums, public spaces. But in my early years, I was focused on survival: putting myself through school, building a career, and learning to adapt. Only later, once life felt more stable, did I allow myself to explore the arts more fully: taking dance lessons, studying piano, and taking up photography, especially bird photography, and eventually fully committed to fine art as my true calling.

Because I didn't grow up favoring one style, both old and new speak to me: the careful craft of traditional masters and the daring expressiveness of contemporary art. In my own practice, I find myself blending the two, using old-fashioned techniques to tell stories about the world we live in today.

(L) Weapon, oil on canvas, 72”X26”

HL: You have created in two seemingly very disparate sectors, on one hand, the technology sector as a software engineer, and on the other, now as a fine artist. What do engineers see in the world that artists may tend to miss, and what do artists see of the world that engineers might not see?

(L) Other Places in Time , oil on canvas, 24”X18”

SS: For me, engineering and art reflect two different ways of seeing, part versus whole, precision versus ambiguity, logic versus intuition. As a software engineer, my work emphasized teamwork and clarity: each person contributed a section of a larger system defined by requirements from marketing or customers, and the goal was efficiency, clarity, and correctness. There was always a right and wrong; success was measured by being bug-free and running smoothly.

Art, in contrast, is both solitary and open-ended. From vision to execution, the choices are all mine. There are no absolute rules—good and bad depend on perspective and objective. Even so, my engineering past stays with me: when I receive critique, I treat it like debugging—an opportunity to refine and discover what's hidden. Where engineers see black and white, art lives in shades of grey; together they give me the full tonal range of the world.

HL: As you were raising your family, you rediscovered your passion for art. What is the story of this rediscovery of your passion for art?

SS: During the years of raising my family, working, and keeping up with daily responsibilities, I lost touch with myself. Life was full yet strangely unfulfilled, though I couldn't quite name it. So much of my time and focus went to what the kids want to do or need to do, while I put aside my own desire. Over time, I began exploring little things that sparked curiosity: dance, piano, photography, and eventually painting.

In 2014, after climbing Mt. Kilimanjaro, I suffered a pulmonary embolism and spent a week in the hospital. That sudden confrontation with mortality forced me to pause and question what I truly wanted in life.

Getting to know oneself is truly a conscious effort, as time has wrapped layers of things around the genuine me. It's not easy to answer what I really want in life. The question became the starting point of a journey. Around that time, I had begun taking art history and studio classes. Immersing myself in drawing and painting rekindled a long-buried passion, which led me on the path I'm on today.

HL: Noting that it was a rediscovery of your passion implies there was a previous discovery that was later set aside for some time. Can you tell the story of your initial discovery of art and what led to putting your passion away until more recently?

(L) Crmpl IV , oil on canvas, 60”X48”

SS: My first discovery of art came in college when I took a drawing class to fulfill an elective requirement. I loved the process of observing, translating, and creating. It gave me a sense of joy and focus I hadn't felt before, and there is no test or grade pressure; it felt freeing. It became something I thought of simply as "fun". But I knew it wasn't my major, nor did I see a practical path to pursuing it seriously.

When I immigrated to the U.S., the urgent realities of survival took over. I chose engineering because I thought it would be a stable source of income, especially for someone new to this country. Art slipped into the background while I focused on building a life and career. Looking back, I see that the passion was never gone; it was just buried, waiting to be rediscovered.

HL: Your artwork focuses on consumer culture in the United States. Before this series started, what inspired you to begin on this path of painting these elements of society that seem as prescient as ever now?

SS: I used to like shopping, drawn in by the aesthetic, the function, the symbolic, and the spectacle of it all, a way of "making up" for what I missed growing up. I then began painting my surroundings. Over time, this practice led me to notice a pattern: the satisfaction of buying something I thought I desired faded quickly. I question the difference between "need" and "desire."

In the middle of the Commodity series, a vivid memory surfaced: parting with a pair of green pants my grandmother made for me. That moment helped me realize how objects carry more than practical use; they hold memory, love, and identity.

At the same time, I became aware that the culture of buying more, producing more, and consuming more suggests that all this 'more' must come from nature. The earth inevitably responds, often with disasters. My painting "9.9.2020,37.7018464419476, -122.40675640172758" about the wildfires in California on 9/9/2020 grew out of that realization.

HL: As a software engineer with a background in tech, who is now painting humans' deep connection to their screens, what do you make of the massive changes that we are seeing in society and individuals due to new technology?

SS: My first encounter with a screen was in middle school, watching television for the very first time. For my children, however, screens have been with them since birth, molding how they learn, play, and communicate. The speed and reach of this transformation are astonishing: technology has collapsed distances, connected communities, and opened new possibilities, but it has also introduced fragmentation, distraction, and new forms of dependence and distraction.

Of course, this is part of human history through the industrial revolutions. The steam engine compressed time and space; Electricity interrupted humans' circadian rhythm but did bring comfort and speed in life; the transition into the digital age exploded with information, while we are hyper-connected and resourceful, anxiety slips in. The smartphone has become less of a phone than an extension of ourselves. Are we edging toward becoming cyborgs?

Technology evolves at an exponential speed, while the human brain and cognitive abilities remain analog. This conundrum impacts our society in big and small ways. Some are good and some are not. In "Other places in time," I portray my mom sitting in her walker while enjoying time on her iPad. Her "freedom" at that moment is redefined by her ability to connect to the outside world through a device. Now with AI and cyber systems, human is replaced by machines. Only time will tell where and how we are heading forward.

As an engineer-turned-artist, I see screens as cultural mirrors, showing us who we are becoming. They redefine intimacy, presence, and even memory. In my work, I try to capture this double-edged reality: the ways screens connect us when we're physically limited, as with my painting of my mother using her iPad, and the ways they hold us back.

(L) A Father’s Gaze (a portrait of my father), charcoal pencil on paper, 24”X18”, (R) Through Her Eyes (a portrait of my mother), charcoal pencil on paper, 24”X18”

HL: Your artwork focuses on identity, which is fascinating as identity is often culturally constructed due in no small part to our environment. Having lived in China and in America, worked in tech, raised a family, and now working as a fine artist, can you talk about the nebulous nature of identity and how these incredible life experiences have affected how you see yourself?

SS: Identity, for me, is fluid and multifaceted. I carry many roles: mother, daughter, wife, woman, immigrant, artist, consumer, and each carries responsibilities and expectations that form how I move through the world. Rather than fixing myself in categories based on birthplace, culture, skin color, education, and profession, I see identity as something always in motion, shaped by experience and awareness. Life is an obstacle course; how I take on each one changes me. Whatever life throws at me is an opportunity; how I face it forms my identity. Each time I pass a liminal space, I see things, myself, and others differently. I used to fear uncertainty, but now I learn to embrace it. Something good might come out of it. Sometimes what feels painful or meaningless, like a bucket of used tissues in my "Crmpl I" painting, can reveal unexpected beauty.

(L) Lunchtime, oil on canvas, 22”X28”, (R) Haircut oil on canvas 24”X18”

HL: There is a powerfully humanizing painting you made in which a man is feeding a person in a wheelchair. Who are these people, and what is the story and inspiration behind this painting?

SS: They are my mother's friends, a couple who have been married for many decades. The wife developed Parkinson's disease, and in its later stages, she could no longer feed herself. The husband gently helps her with lunch, an act of quiet devotion that deeply moved me. In that small gesture, I saw the essence of love, commitment, and tenderness.

Most recently, I painted my parents in "Haircut": my mother giving my father a haircut, something she still does in their eighties after more than sixty years of marriage. These ordinary gestures may seem ordinary, but to me, they carry extraordinary meaning: the strength of human connection and the quiet beauty of enduring care, themes I continue to explore in my work.

HL: You created a collaborative series with your late grandfather's Chinese ink paintings, bridging generations, cultures, and, as you say, bridging "tradition and innovation". How did this collaboration come to be, and what did your grandfather mean to you personally, and how has he inspired your art practice?

SS: My grandfather passed away before I was born, yet his ink paintings were a constant presence in my childhood home. I grew up with his work on the walls, knowing him only through his art and stories my mom shared. Ironically, while he was devoted to painting, he discouraged his children from pursuing art, urging them toward "useful" professions—medicine, nursing, research. They followed that path, but he always regretted that his own paintings were not seen by more people.

For years, I have wished to create a dialogue with his work. When I began bird photographing and painting them, I realized I could weave our practices together across time and generations. By painting birds into his ink landscapes, I created a conversation between his world and mine. For him, painting was an escape from the weight of life; for me, photographing and painting birds carries that same solace.

This collaboration has become both personal and symbolic: an honoring of his unfulfilled wish, a continuation of our family's creative lineage, and a way of bridging tradition and innovation. On the canvas memory, loss, and discovery come together, creating a space where our two voices finally meet.

HL: There is a painting you created in which the viewer sees a first-person war video game and the reflection of a young person's face on the screen. Can you talk about the symbolism and sociological significance of this painting?

SS: I titled this painting "Battle" because it literally captures a game scene of battle and reflects a personal one as a mom tries to get her son's attention over the immersive pull of video games. On the screen, we see the intensity of a first-person war game, but what lingers is my son's faint reflection. For me, the reflection symbolizes the innocence caught between simulation and reality. The true casualty isn't in the game. It's the human connection that gets lost when digital media takes over.

This piece came from my frustration as a parent in the digital age, where attention is constantly fragmented, and genuine connection often feels like something you must fight for. It's both a critique and a deeply personal moment, a way of translating the emotional tension of family life in a world dominated by screens.

HL : You created an incredible painting where the viewer is looking at a scene from above, seeing four youths playing video games amidst stacks of books, and in the corner of the room, we see you observing the entire scene as you hold a book in your hand. What inspired this painting, and how do you, as someone who has designed software and seen such generational changes, see the future of art, human connection, and society as a whole amidst incredible social changes due in no small part to new technology?

SS: This painting, Family Time 2, along with Family Time 1, grew out of my reflections on how my family spends holidays together. The work depicts four siblings seated close, playing the same video game, yet each remains isolated within their own screen. Their bodies are near, but their gazes fragment the space, creating a paradox of connection and disconnection. My self-portrait "Contemplate" hovers in the background, a reminder of presence beyond the digital. Only the dog meets the viewer's eyes, grounded in here and now.

As both a parent and a former software engineer, I've seen technology's capacity to connect, and to divide attention and intimacy. Here, I paint that fragmentation, while in Other Places in Time, I explore a counterpoint. Together, these paintings reflect my belief that the future of art and human connection lies in navigating this duality: technology as both barrier and bridge. By slowing these fleeting digital encounters into painted form, I invite viewers to pause, reflect, and question what it means to remain fully present in an age of screens.