Enrique Chagoya

Enrique Chagoya holds a BFA in printmaking from the San Francisco Art Institute and an MFA from the University of California, Berkeley. A professor at Stanford University, he shows nationally and internationally, including a 2007 retrospective organized by the Des Moines Art Center in Iowa which travelled to the UC Berkeley Art Museum and Palm Springs Art Museum, the 17th Biennale of Sydney, and a 2013 exhibition at the Centro Museum ARTIUM in the Basque capital of Vitoria-Gasteiz (Spain) which went to the CAAM in the Canary Islands. His work is held in the permanent collections of SFMOMA, the de Young Museum, LACMA, the National Museum of American Art, the Des Moines Art Center, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Museum of Modern Art, New York, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, and the New York Public Library.

This interview is a long read with Enrique Chagoya.

It is part of an ongoing series of interviews with artists on censorship in the arts.

The following are excerpts from Enrique Chagoya’s interview.

Hugh Leeman:

Enrique, as a child, you grew up in Mexico, and there was an Indigenous nurse who took care of you. It changed your perspective on racial inequality within Mexico and expanded your understanding of Indigenous histories that continue to influence your artwork. Who was this nurse, and what can you tell us about her story?

Enrique Chagoya:

My understanding of Indigenous heritage in Mexico didn't happen all of a sudden; it happened over my entire childhood and youth. It was a gradual process of discovery and awareness. My nurse, Natalia, was a significant part of this. She was a Mazahua Indigenous woman, and the Mazahua are a branch of the Nahuas who speak the same language from the state of Mexico. This is the larger territory where Mexico City is located.

Natalia took care of me while my mom worked as a seamstress and my dad worked at the central bank. My dad had an administrative and investigative job going after con artists who forged money. We can talk about that later, as it was very influential on me. Natalia would take me everywhere she went, to get tortillas, to the panadería for bread. She would often go with her boyfriend, who was also Mazahua but had a job as a soldier. I used to refer to him as her "general," and they would both laugh. At some point, I couldn't understand what they were talking about because they were speaking Mazahua, the language of their people. I was studying a little bit of English in kindergarten at the time, and I began to try to talk to her in English, and they both laughed because they couldn't understand me either. The connection I had with Natalia was emotional, not something I immediately understood in a historical or academic way. Over time, as I grew up, I became more aware of my own heritage and my own racial mix.

In Mexico, the ethnic identity wasn't as intense as it is in the United States. For many historical reasons, Mexico had, and still has, racism against Indigenous people and people of color, like African Mexicans, but there has been a history of very intense commingling. So much so that everybody got mixed with everybody. As a result, everybody has a little bit of everything in them, and the society is not as segregated, with the exception of some areas like the Yucatan Peninsula. Because there was a war by the Mayans who almost took over the peninsula in the 1800s, it's still very segregated. If you ever go to Merida, you'll see a very dark-skinned Indigenous population and then white Mexicans, many of whom are blonde. There are also a lot of Americans moving there, so it looks almost like an American city to me. The rest of the country is a mix. You still see people from different ethnicities, but it's not as extremely divided as what I found here. My personal experience from visiting Merida a few times is what I felt when I moved to the U.S..

Here, I somehow became "Mexican." Suddenly, you're cornered into an identity, Jewish, Chinese, African-American, and then you have gender identities that are evolving all the time. While these identities exist in Mexico, there wasn't this strong political banner behind them. One of my best friends in Mexico was gay; he shared his studio with me. We were best friends; he talked to me about his boyfriends, and I talked to him about my girlfriends. We went on vacation together without any sexual interaction. We were just friends, and I was lucky to be able to paint in his brother's building, which had a beautiful view of Mexico City's Reforma Avenue. This lasted about two years until his brother needed the space.

I also had Jewish and Chinese-Mexican friends. I didn't even think about their ethnic backgrounds. I had a friend named Silvia Gruner, a contemporary artist in Mexico, and it never occurred to me she was Jewish. I had a friend named Luisa Chu, and I didn't even think about her last name being Chinese. I also had African-Mexican friends whom I never saw as anything but just other Mexican kids. They had curly hair and were darker-skinned, but so was I.

When I first visited the U.S. as a tourist, I managed to make money selling Christmas postcards when I was a teenager. I went to the factory, got a catalog, and then went to a leather press for samples. I dressed up in a business suit and a little tie, and went to the bank where my dad worked. I went in August and said, "Hey, I have some Christmas cards. You want some?" They were surprised, but I convinced them it took a while to get personalized cards published. I sold a lot and made about $2,000 in a month. I felt guilty, like I was stealing money, but it was just my labor for being an entrepreneur, I guess.

I used the money to travel with a cousin and a friend. We took a bus all the way from Mexico City to Texas just to shop. I bought art books, Levi jeans, tennis shoes, and art supplies. I came back with a ton of stuff and had to bribe the customs officials in Mexico to let me through without having to pay taxes. I ended up paying some kind of a tax anyway, without a receipt, so it was fun and a good experience.

Eventually, I wanted to study art, but my dad, who was also a painter, was maybe the wrong role model for me, since he didn't make a living from it. So I decided to try to understand what was going on in Mexico instead. This interest started when my mom came home from work in 1968 crying. She had witnessed a police officer shoot a kid who was about my age, 14 or 15. I cried with her and wanted to understand what was going on in the world. To this day, I still don't fully understand. My parents weren't political or ideological; they were religious but not fanatics. They had a great sense of what was right and what was wrong, and my mom was the first to inspire that in me.

On my dad's side, he was very respected at work because he was one of the few honest people around. The Bank of Mexico is where they print the money, and they had internal security to check for fraud. My dad caught quite a few people. He would visit them in prison to interview them and try to understand why they were doing what they were doing. He became friends with some of them because they were artists, con artists, but good visual artists who were great imitators. My dad would bring them art supplies, and in return, they would tell him everything, which he said worked better than waterboarding.

When I was about 10 years old, my dad took me to his office. It was a museum of forgeries, a museum of crime. He had the plates and the forged money bills and the tools they used. Some people even used the tip of an agave plant as an etching needle. I was fascinated by how they made things, and I think this influenced me in the long term, as I continue to make things that look like others. I did a series of etchings that look like Goya's Disasters of War and Goya's Caprichos while I was a student at the Art Institute and later at UC Berkeley. The influences from my parents and my nanny have stayed with me and shaped my interest in trying to understand the world and what is happening in society.

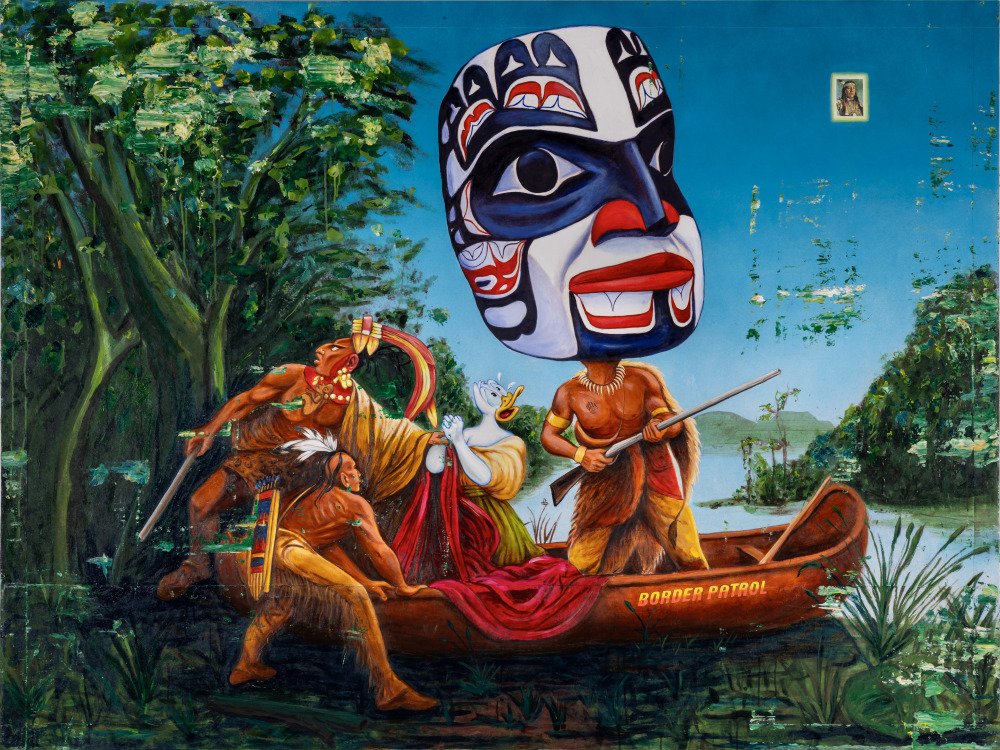

HL: Let's connect this incredible story of your nanny, your mom, your dad, and this influence, with the complexity and contrast between your experiences in Mexico and then in the United States, particularly as it relates to racial relations and political perceptions through the lens of your art. You're well known for your artwork referred to as "reverse anthropology" and the "cannibalizing of Western images." Can you offer a bit of context on what these terms mean to you?

EC: My studies of social sciences are probably what affected these ideas. After my short and disastrous semester of architecture, I went to study economics. I loved it. At the time, the school of economics in Mexico was amazing because we had so many faculty members who were refugees from South America; this was in the mid-70s. We had former deans of universities, like Rolando Pigros, who I believe was the dean of the Catholic University in Buenos Aires. He had to leave after the coup d'état by the Videla Junta. We also had professors who were refugees from Chile after the coup by Pinochet, and from Uruguay, Brazil, and Central America.

We studied economic theories for Latin America to develop its independence from the West. After most Latin American countries gained independence, there were many attempts to develop them in a way that the U.S. had, and the U.S. had been a model for Latin America for centuries. Mexico, for example, has the same three-part government structure as the U.S.. However, Mexico's economic system was affected by the Mexican Revolution, which was a nationalist revolution that blended a large public sector with a large private sector. It's not socialist, but it has capitalism that is very much regulated.

We also studied socialist economies and criticized them for the bureaucracies they developed. We studied Marx, and we saw him as the best critic of capitalism in the 1800s. His theory of the accumulation of capital, where private hands appropriate the value produced by society, seemed unstoppable to us, and we see it happening today. He's like Darwin, he's dated, but not obsolete. That's why even today, people label him as "evil" without having ever read his work. He really attracted a lot of movements through his ideas that were happening in the 1800s, especially after the American Revolution and the French and other revolutions in Europe. These revolutions needed an ideological content, which came from political science and philosophy, particularly German philosophy from Hegel.

Hegel was a conservative and religious philosopher who developed the idea that things change through contradictions, the so-called dialectical philosophy. He believed that a thesis and an antithesis come together to create a synthesis, and this process moves in a spiral toward a resolution. For Hegel, the resolution was God. Marx took this theory and applied it to capitalism, where the main contradiction was between labor and capital. These two elements depend on each other, so one cannot exist without the other. There is no capital without labor, and no salaried labor without capital.

HL: Enrique, I want to connect this to your shows, Déjà Vu at Anglim/Trimble in San Francisco and another show at the Portland Art Museum. What you're talking about with Marx and these different philosophies is a repetition that takes place in society, with everyone borrowing from someone else, which connects to the idea of "cannibalization" that was mentioned previously. You've told me that the issue of immigration is more complex than it seems and that it's effectively a Trojan horse for a totalitarian attempt. Tell me about Déjà Vu and how that refers to the Trojan horse of immigration.

EC: Just to finish my critique of Marx, we criticized him for being too Eurocentric and overly Darwinist. He thought whatever happened in Europe would eventually happen in the rest of the world and didn't bother to study Latin America, Africa, or Asia. For instance, he saw Bolívar as an autocratic landlord, but Bolívar was no different than Washington. He even celebrated the U.S. victory in the U.S. Mexican War and had nothing to say about the fact that the war started because Texas wanted independence from Mexico to keep slavery, which had been abolished in Mexico. Lenin himself had a hard time explaining why the first socialist revolution happened in Russia, the least developed country, rather than in a developed one like England. He had to quote Goethe: "The tree of theory is gray while the tree of life is green." You can have the most beautiful theory, but reality will be different.

The border was moved to the Mexicans. The early Mexicans did not move to the U.S.; the U.S. moved to the Mexicans. The history of the Chicano people is the history of Mexicans who stayed in this country and became its ancestors. This is different from my own story. I immigrated later and wasn't a refugee, but when I came here, I was afraid. I had studied all the coups and boycotts organized by the United States against nationalist movements in Latin America. Many of these movements, like Sandino's in Nicaragua or Zapata's in Mexico, were not socialist in the beginning. Even the Cuban Revolution was a nationalist movement before it became socialist. All these movements were boycotted by the U.S..

I moved here with fear, but I wanted to continue my studies. I was disappointed that the critical perspective I was used to wasn't as present here. I found that the theories of Milton Friedman, which were first applied in Chile under the dictator Pinochet, ruled the world. The idea that markets should rule the economy, until they fail and need a government bailout like in 2008. All these economic theories and this idea of historical repetition are what shape my art. Immigration happens because people are attracted to economic development centers. The first immigrants to this continent were the Indigenous people, but when the Europeans rediscovered it, they were also undocumented immigrants. The Spaniards and the Pilgrims came without passports and acted against the laws of the Indigenous people. Today, it's not so different; most immigrants are good people escaping difficult situations.

Immigration is a problem in Europe right now because the unequal concentration of capital hasn't stopped. We live in a time when the concentration of capital is so huge that people are angry. And there are politicians who channel this anger against the most vulnerable, which in this country is immigrants.

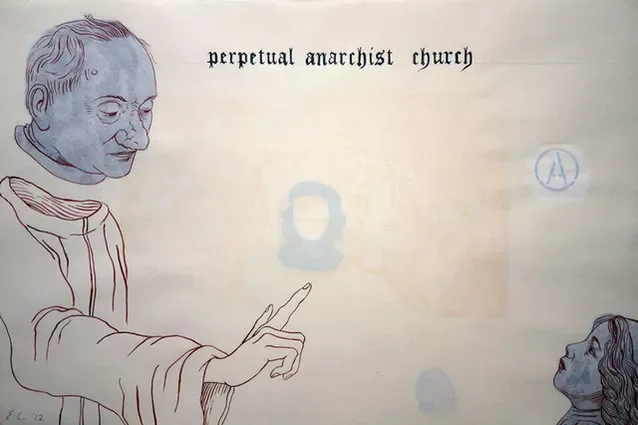

HL: Let's connect this to censorship and the controversies in Christianity and colonization. In many liberal spaces, we often talk about decolonizing spaces, but we seldom implicate Christianity in those conversations. Yet, your artwork does just that, and it's led to controversies for you more than once on two different continents. Can you talk about the role of Christian imagery in your artwork and those controversies?

EC: For me, it's a reflection of history. Conquest happened "first with the sword and then with the cross." In the name of Christianity, Indigenous people were massacred throughout the Americas. According to U.N. statistics from the 1970s, the Indigenous population was reduced by 90% in the first 100 years after the arrival of Columbus. The ones who didn't die from illnesses were killed in the conquest of Mexico, for instance. There are even illustrations by Indigenous people showing priests and soldiers burning their leaders for refusing to convert. It was an exercise of power, not an exercise of love, as taught by Christ. I criticize the institutional elements of any religion because they become more like a political institution. The Catholic Church developed its power through the Holy Inquisition, which could execute anyone they decided was a "messenger of the devil."

This is not too different from censorship today. I'm not surprised that science is being censored now. It's just like in absolutism, where kings were against science and for religion. We see artists being censored, just like Honoré Daumier in France, who did a lot of lithographs against the king and ended up in jail more than once. We are seeing that kind of censorship today, especially with what is happening with the Smithsonian and the Kennedy Center. There are threats to universities for their diversity and inclusive policies, as if they were fighting discrimination. All of this is power trying to make sure that there isn't a threat to its concentration. History repeats itself in these cycles where there is a concentration of wealth and power, which leads to an interest in censorship and control over what is understood as reality.

HL: Your artwork has been censored in the past. In one such controversy, a Christian woman destroyed one of your artworks with a crowbar at a show in Colorado. Yet later, referencing that same show, a local evangelical pastor, Jonathan Wiggins, reached out to commission a painting for his church. How was it that Pastor Wiggins was able to see things so differently in your artwork than the Christian woman who destroyed it?

EC: Well, the difference is that some people just "see with their ears"; they believe what they've been told to believe. Others see with their eyes and their own independent minds. Censorship is usually a sign that you are doing something that threatens power, especially when you are speaking truth to power. What is happening in the world is that the wealthy have gotten super-wealthy in the last 30 or 40 years, since the Reagan administration began to end regulation. The middle and working classes have lost income dramatically. The American dream is collapsing in front of our eyes. This is not the first time it's happened; we had a "Gilded Age" before, but now we have a "Gilded Age" on steroids. This is what I'm talking about when I say history repeats itself. Hegel, the conservative philosopher, said history repeats twice, the first time as a tragedy, and the second as a farce. Marx was talking about Napoleon III compared to the first Napoleon. But I think humans are the only animals that trip twice on the same stone. History repeats, and the first time is a tragedy, but the second time is a catastrophe, because we should have learned our lesson.

(Above left) Commissioned artwork by Pastor Wiggins

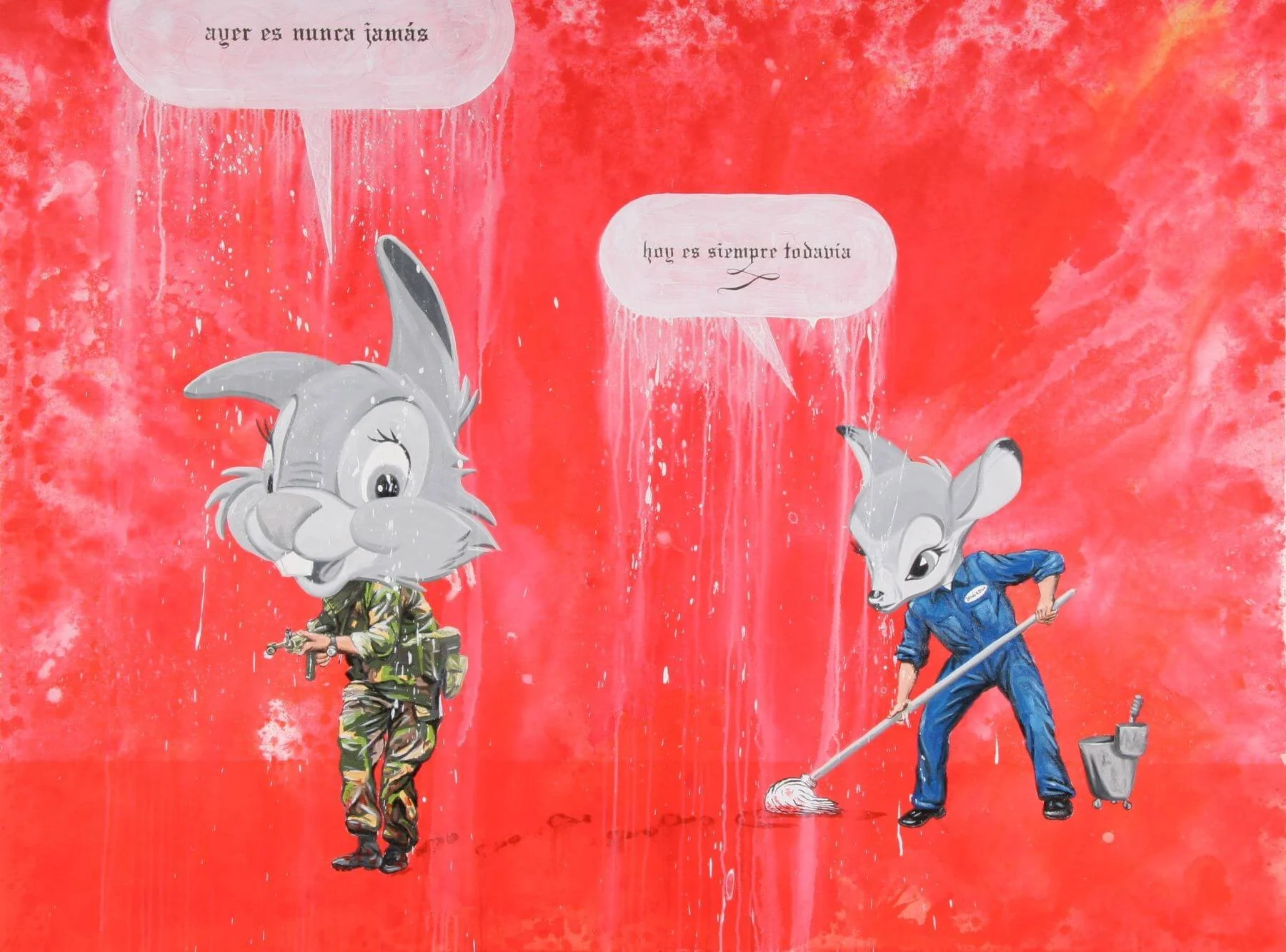

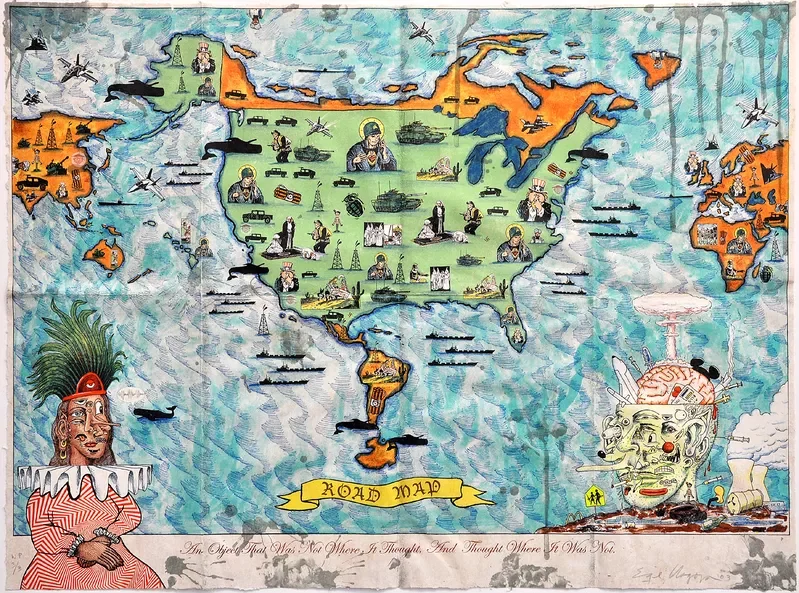

HL: Let's connect that idea of history repeating, censorship, and the targeting of individuals like yourself for your stances and artwork. There are a few paintings in your show, one of which is titled An Object That Was Not What It Thought. There's also Danza Macabra and a multi-paneled piece with friendly face characters at the border wall. These pieces are clearly critical of current policy and censorship, yet you continue to move forward. How do you confront that fear, and how do you address the current situation unfolding across the nation through your artwork and the stances you're taking in academia, your art, and the classroom?

EC: This is where I see history repeating itself, especially when autocracies come back and start developing ideologies where science and art are suddenly subversive. I believe we are going through a moment where a totalitarian government is evolving. The recipe for a totalitarian government, which we studied in social sciences, is when all the independent institutions of the state stop being independent, and there is a single ruling party that rules the country. Then, the party is replaced by a supreme leader. This happened with Stalin and Hitler, and Putin is doing it now. This recipe is happening in this country right now. Every week, we see how one thing after another is being eliminated. Thankfully, it's not totally gone, which is why in my painting An Object That Was Not What It Thought, the country is not completely sunk in water; it's just beginning to sink. It's an upside-down country where truth is false, and falsehoods are considered the truth. Reality is no longer reality.

HL: Let's dig in on that, because that's a powerful statement. You made an artwork on censorship, it has a highway with crocodiles. Because of the challenges conveyed in your artwork, some people are speaking of leaving the country. You mentioned to me in a previous conversation that, "I don't want to run like an exile. This is my home." Tell me more about that idea of staying here and speaking up against censorship and the injustices of this administration.

EC: I hope things are momentary. The problem is how long this pendulum of history is going to last. Nobody knows. But I see it as temporary, and things change eventually. Totalitarian states collapse one way or another. Sometimes it's violent, which I hope doesn't happen here. Other states collapse when the supreme leader dies, like in Spain after Franco died. Other places collapse by their own weight, like the former Soviet Union, because the government lacked popular support and was corrupt. This is the part of history that keeps repeating itself. Hegel said it repeats twice, as a tragedy and then as a farce. But I believe humans are the only animals that trip twice on the same stone. History repeats, but the first time is a tragedy, and the second time is a catastrophe. We are seeing it in many places. I have Jewish relatives who are appalled by what is happening in Gaza. If anybody should be sensitive to human suffering in history, it's the Jewish people. But we cannot generalize all Jewish people for the government of Netanyahu, just like you can't generalize all Russians for Putin. People are complex, and the problem is that we are suddenly being ruled by autocracies.

I believe in the power of the American people. I have hope that they will resist against whatever the oligarchs in this country are trying to impose on us. I think the same thing will happen in Israel, where people will overcome the current horrible war. You cannot fight a monstrosity by becoming a monster. You cannot fight inhumanity by doing something that is 10 times worse.

HL: Let's talk about that to conclude. Your show is such a powerful message, and it has been a recurring theme throughout your entire career. If these two shows, at the Portland Art Museum and Anglim/Trimble in San Francisco, if you could have the autocrats and oligarchs you're referring to attend these shows and see your artworks, and you could magically convince them of something, what would you want them to understand?

EC: I don't know if they would. Most likely, I'd be put in jail or sent away from this country. I don't think you change the world with art. At most, you create thought-provoking situations and discussions. People do what they do out of economic pressures. If they believe that the ends justify the means, they become immoral. Nobody should use that idea, because it's an excuse to do something inhuman to get to your ends. Pinochet said he was saving the country, just like Hitler thought he was saving Germany, or Trump says he's making America great. All these dictators see themselves as messiahs, but in the end, they act like the opposite.

Art is not going to change them because they are locked in their privileges. People tend to think based on their privileges. I'm not saying every wealthy person or every oligarch is evil; there are exceptions. But what is happening is very much connected to this. The ideas of society are related to what is happening in the economic conflicts of that time and place.

I think what is happening in this country is unique and different. The American people, which is a big question because it's so many different groups, are very rich in culture. The greatest export this country has, besides commodities, is culture: arts, music, and theater. That happened because a lot of people from all over the world moved here and interacted with each other. We have great food, great music, great art, and great shared histories. Now, we are facing a wannabe autocracy that wants to eliminate all of that. I don't see it happening, at least not overnight. If it does happen, it's going to be very chaotic and could turn very violent. I hope not.

The resistance in this country is coming from daily life, not from some organized group. It's happening because people just need to have a life, and the government is not letting them. The economy might collapse because tariffs will create a tax on everybody. The lack of immigrant labor will affect production. Industries that Trump wants to develop will have no workers. Once that starts to affect their pockets, I believe that if they are pragmatic, they are going to have to stop. That's what will change their minds. Not my art. I wish my art would work that fast, but what will change their minds is when their pockets are hit and when the lack of ethics and the corruption that is happening becomes undeniable.

We are being ruled by a convicted felon right now. I don't think he is the main problem; the main problem is all the people who believe in him. I would like to see this country be great again, but the opposite is happening. We are seeing this country become like any other autocracy in the world. The difference is that the American people are not used to having autocracies like Russia has. Here, at least, there was a more or less functional electoral system and independent institutions, which no longer exist in the same way. But that could be reversed. I don't know how it's going to happen, but I know that one way or another, it has to, or this country is no longer going to be this country.

Hugh Leeman: Enrique Chagoya, that is a powerful thought to end on. Thank you very much.

Enrique Chagoya: Thank you.