Dean Larson

Artist Dean Larson was raised in Palmer, Alaska, where he first learned painting under the mentorship of Alaskan Artist Fred Machetanz. After graduating from Willamette University in Salem, Oregon, Dean moved to Baltimore, Maryland, for graduate studies at the Schuler's School of Fine Art and Towson University. In 1997, the artist moved to San Francisco, CA. Dean's commissioned portraits and studio paintings can be found in museums and other public collections in the United States and Europe. Larson has also taught painting (mainly cityscape and landscape) at the Academy of Art University in San Francisco since 2006. He maintains a studio near Mission Dolores, the original Spanish Mission in San Francisco. Larson has painted the portraits of Senator Ted Stevens, which hang in the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C., and Senator Mark Hatfield, which hangs at Willamette University. Larson's work is also included in the collections of the United States Institute of Peace (USIP), the Alaska State Capitol, Triton Museum of Art, and the Smithsonian's National Portrait Gallery

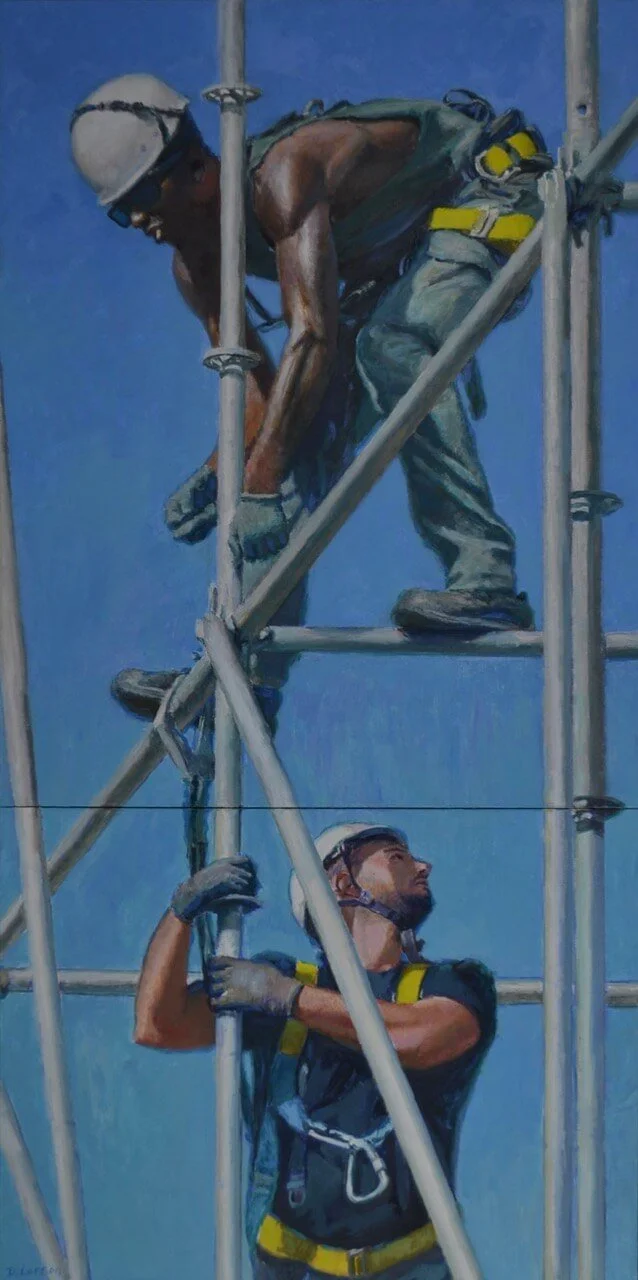

(Above) Scaffolders, oil on canvas (diptych), 48x24 in

Hugh Leeman: You grew up in Palmer, Alaska, and were mentored by Fred Machetanz, a defining figure in Alaskan art. Could you share the story of moving from Michigan to Alaska, crossing paths with Machetanz, and what particular lessons from that relationship continue to resonate in your work, perhaps a specific painting that reflects his early inspiration?

Dean Larson: My father was working as a part time teacher and coach at a small school in Northern Michigan and was looking for a full time job and reached out to his relatives, including his uncle who had moved to Alaska in 1935 with a group of colonists from Michigan, Minnesota and Wisconsin which the U.S. government sponsored in order to have depression era farmers move to Palmer to settle the area and grow food for Alaskan residents instead of having it all shipped in from Seattle. One day in 1959, this uncle called my father and said the school in Palmer was looking for a teacher and a coach, and would he be interested? So my parents made the decision to load up the car and make the seven-day drive and move to Alaska. As it happened, Fred Machetanz settled in Palmer in 1951, and he and his wife, Sara and their son were about my age, and we were longtime friends, and through Traeger, I got to know Fred.

HL: Your portrait of Senator Ted Stevens, commissioned by the Ted Stevens Foundation and unveiled in the U.S. Senate in 2019, includes deeply symbolic details from a Tlingit box to his favorite fountain pen and books bearing crests of UCLA, Harvard, and his WWII service. Can you walk us through the creative journey of creating this painting from your personal connection as his former intern to the moment you captured him "at work" and what narrative you aspired for each symbolic detail to convey?

DL: During the Summers of 1980 and 1981, I worked in Senator Stevens's Washington, DC office and got to know Senator Ted and also his wife, Catherine. They were both huge supporters of the Arts. The President of the Senate and President Pro Tempore (PPT) of the Senate are eligible to have their portraits included in the Senate Portrait Collection. Senator Stevens was President Pro Tempore from 2003 to 2007. In 2018, we began work on the project to create a portrait of Senator Stevens in his Capitol Office that overlooked the National Mall. In his hands, he holds a whip count of votes. In the background, the World War II, Washington, and Lincoln monuments show in the distance, along with some of the Smithsonian buildings. Also included is the United States Institute of Peace (USIP), for which Senator Stevens and Senator Daniel Inouye of Hawaii helped procure funding for the new building. Senator Stevens had a long, rich tenure in the Senate, and there are many other items included that symbolize his and Alaska's evolution over the years.

(L) Portrait of Mark O. Hatfield, United States Sentor oil on canvas 42x30 in (R) John Ulatowski, oil on canvas, 40” x 30”

HL: Your portrait of Oregon's Senator Mark O. Hatfield hangs in Willamette University and represents another high-profile commission, along with a series of artworks depicting Physicians. Could you tell the story of how that portrait with Hatfield came to be and what inspired your series of paintings of physicians?

DL: When you're an artist, you work and work, and life is filled with rejections, but once in a while, things "drop out of the sky" and good things happen. As it turned out, Antoinette Hatfield, Senator Mark Hatfield's wife, happened to read my biography at an exhibition in Washington, D.C., and she noticed I had attended Willamette University for undergraduate work. One day, while working at my home/studio in Baltimore, I received a call that she and Mark would like to take a drive from Washington, DC to Baltimore to visit the studio and see available work. Antoinette had a gallery in Portland and was looking for artists to show. The next thing I knew, Antoinette and Senator Mark both appeared on my doorstep. We hit it off right away, and I ended up doing solo and group exhibitions with her gallery and also got to do the Senator's portrait for Willamette University, which is where Senator Hatfield had attended college. We did one of the sittings for the portrait inside the Senate Appropriations Committee Chairman's office in the Capitol.

At the Smithsonian's National Portrait Gallery, I was looking through the files of portrait artists and met Karen Spiro, who was there to do the same thing. This chance encounter led to us working together for over 30 years with her company, primarily-portraits.com and together we've worked on many projects for Sidney Kimmel Medical College at Thomas Jefferson University and other colleges and institutions.

HL: One of your more intimate subjects is your former partner, a ballet dancer at San Francisco's Lines Ballet studios. Can you share how it felt to paint someone you shared such a personal connection with, and how that process differs from rendering the likeness of public figures?

DL: José I. Ibarra and his dance partner Pete Litwinowicz had a company called DanceContinuumSF for six years, and so helping out with rehearsals and performances became a regular activity. One of the places they would rehearse, the Lines Ballet studios, has large semi-circular Palladian windows that look out over Market Street, United Nations Plaza, and also San Francisco City Hall. The group's dancers allowed me to photograph them regularly during rehearsals, and from that, an entire series of dance-themed compositions was developed.

Ballet Bar, oil on canvas, 30x24 in

HL: Your current show, Urban Visions: Life in Motion, is your first solo Museum Show. You speak of "a desire to go deeper and search for what is most significant and essential" amidst urban life and the accidental moments of diverse human experiences. After the countless hours creating the work for this show, what has that deeper search for the most significant and essential revealed to you?

DL: What "significant and essential amidst urban life" has revealed while making the work for this exhibition is allowing all areas of life to be focused upon, both the beautiful and the ugly. Much of city life is gritty and rough and can often be full of struggles. In a painting, the artist leads the viewer's eye through passages toward some spot of significance. If that spot of significance somehow challenges the viewer's sense of beauty and invites or provokes alternative ideas, then our boundaries of what's essential and ideal are challenged and reconsidered, and difficult conversations can be initiated.

HL: In the same show, Urban Visions: Life in Motion, you encountered countless people observing human interactions in the urban environment how has what you observed in these human interaction's that you paint changed from when you began decades ago to what you observed for this current show?

DL: In the most recent work, there are many examples of what I refer to as "people-scapes." At its most simple form, it is patterns of light and dark shapes of people doing things they naturally do. It's not meant to have any deep philosophical meaning, but as one carefully observes figures in an environment, things just happen naturally! We begin to ask What are they doing there? What are they saying or thinking? What is life like in their shoes?

HL: Your body of work spans public portraits like those of Senators Stevens and Hatfield, and highly personal scenes like the dancers or paintings on site in the urban landscapes for paintings in your show at the Triton Museum. Can you discuss how you navigate the creative and emotional balance between these realms?

DL: That's a good question. Maybe it gets to the heart of the business side of being an artist. For those who are called to be artists, it's not something we do casually; it's something we have to do, it's really not an option. It's how we get on with life. With that acceptance, there also comes a price, and that price is almost never having a regular paycheck. The way we "keep the lights on" is to diversify as much as possible. We can be drawn to many types of subjects, both entirely personal projects and collaborative projects, and both kinds can offer resourceful and inspiring challenges.

HL: Your plein air painting, San Lorenzo Market (2015), came alive through on-site interaction with shop vendors in Italy, who became part of the painting process. Could you share the stories of that experience in Florence?

DL: The outdoor market around the enclosed Mercado Centrale or Central Market in Florence, Italy, is where hundreds of vendors sell their goods, many of which are leather. Each stall has a cart and has a large tent that lines the streets and faces a large center aisle for pedestrians and shoppers. The carts are loaded with goods and are extremely heavy and are hauled, mostly by hand, to and from the nearby depots where they are stored each night. I was out painting one day and set up behind the tents on a sidewalk. One of the vendors was sitting there waiting for customers, and he came up and, after a while of watching me paint, asked me if he could be in the painting, so I added him in. Later on, his friend came up and asked me where he was, so he got added in also. This is one example of the wonderful things that happen when you stop and paint a location instead of snapping a photo and immediately moving on.

HL: Looking across your journey from painting in Alaska and earning prestigious public commissions to your current show at the Triton Museum, how do you envision realism painting and art changing with new technology and the major societal shifts that we are experiencing?

DL: Who knows what will happen with AI getting more and more sophisticated? Some of the AI-generated images I've seen are truly impressive. The thing that always comes up, however, is that if AI can generate something once, it can be generated a thousand or a million times in the same exact way. The thing about purchasing an original painting or drawing is that you have the only one in the world. Each one of us is different, so why not choose to have something that only you will have? For me, I would love to own a Van Gogh painting to look at every day, but availability and cost make that unrealistic. But, there are paintings available that are more approachable that I've collected over the years that I see and appreciate every single day and never get tired of living with them. If you see something you love, go for it, because if you don't, someone else will, and then it will be gone.

HL. As a longtime instructor at the Academy of Art University in San Francisco, you've navigated shifts in teaching brought on by new technologies and the pandemic. Can you share how the classroom experience evolved during these changes and how these shifts might influence the next generation of artists?

DL: My first teaching experiences were in the classroom. Early on, however, they asked me to build a class on cityscape painting for online students. The Academy of Art has had a wonderful online program for many years, and it allows students who often work during the day to have the experience of building a strong artistic foundation similar to on-site students. The online program also allowed students to remain in school during the years of COVID. The online classes offer demonstrations and lots of personal critiques as well as group activities and core content. Recently, students have been using preliminary AI-generated images to see what direction they want to take an idea, but then the student will draw, paint, or sculpt the final work from scratch. The better students realize that artists do their best work when there are set limitations under which they work, so using too much technology only hurts the final result. When the aim is to make your work look as alive as possible, having it appear dead or machine-made is the last thing you want. The work artists are most proud of and the ones that boost their confidence the most are the ones that come from that place within the artist where their own character comes through.