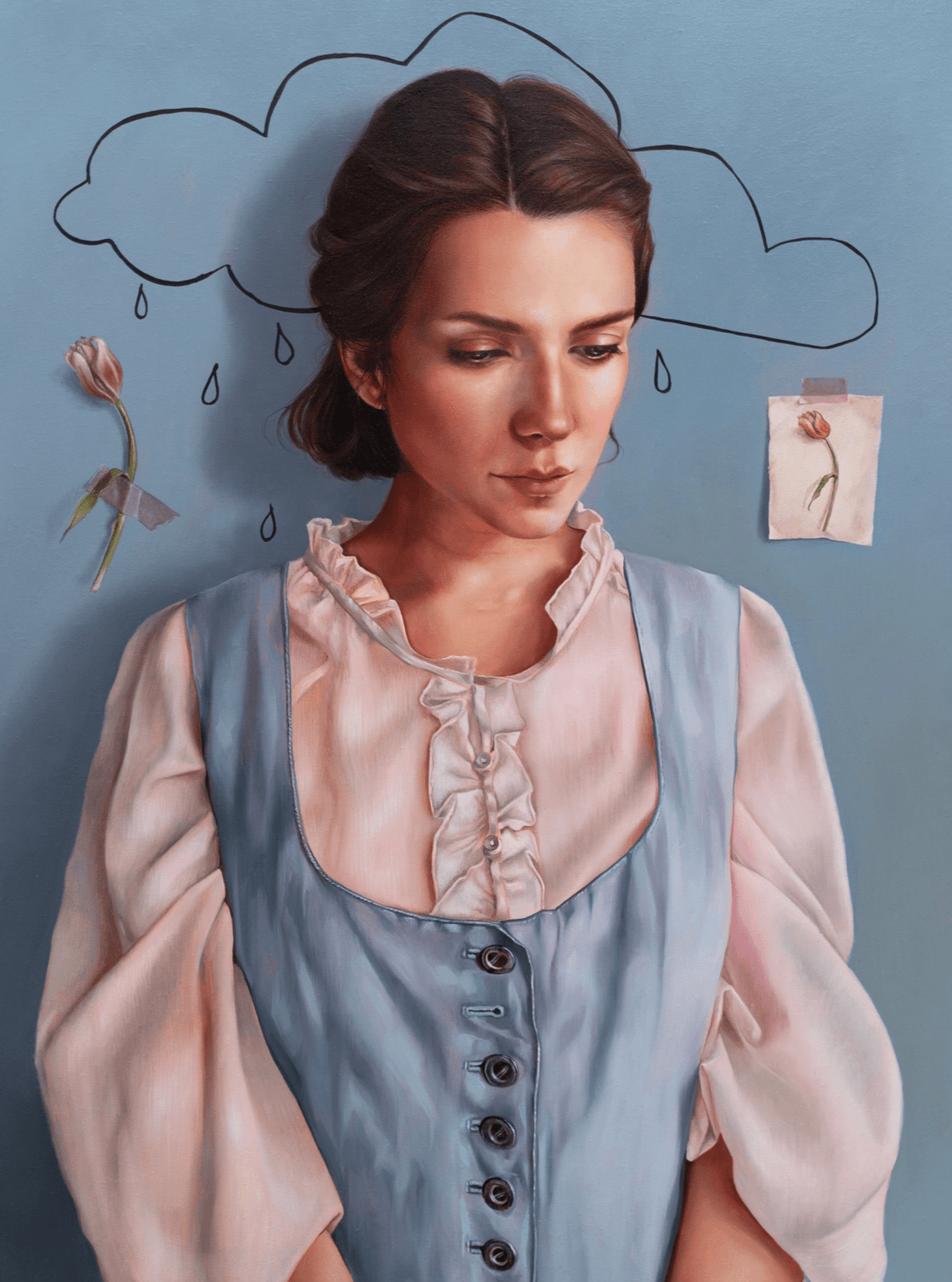

Ana Monteiro, Once Upon a Time, CK Contemporary

By Matt Gonzalez

Archeologists believe self-portraiture’s origins can be found in the handprints discovered in prehistoric cave art, estimated to be 40 to 250 thousand years old. El Castillo Cave in Spain, Quesang Hot Springs in Tibet, Cueva de las Manos in Argentina, and Leang Tedongnge in Indonesia all have examples. The sheer diversity of location exemplifies the innate human desire to leave a record of the self, albeit not exactly what we think of when we evoke the genre. Albrecht Dürer’s panel painting “Self-Portrait at 28 Years Old Wearing a Coat with Fur Collar” from the year 1500 marks the relatively modern period in human history of a painter sitting down to offer us their own visage. The development of the first glass mirrors in 16th-century Venice, replacing polished stone or bronze/copper hand mirrors which Dürer likely used, helped normalize the activity. Since the advent of this new technology, the self has undeniably been an available subject.

Portuguese painter Ana Monteiro certainly understands this. So much so that her current exhibition at CK Contemporary, marking her first foray in the United States, is exclusively an exploration in the style. While many artists paint themselves and thereafter return to the subject occasionally to show changes in their physical self, the aging and fashion styles of a particular time, Monteiro keeps mining the same subject, situating the composition as an exploration in possibilities and competing ideals of what the self is and can be. She does so with a multitude of such engagements and the use of allegory, interspersing references to literary and personal events throughout. These are not self-portraits of how she wishes to be seen or imagines herself, but rather honest offerings of inescapable human emotion. Each one a variation of truth, a seemingly fictional portrayal—and yet, it is precisely this multiplicity that allows them, together, to approximate truth.

The Portuguese writer Fernando Pessoa (1888-1935) employed what he called heteronyms to write poetry and prose on occasion as if he were a different personage. He invented entire biographies of various others, which were actually all himself. In a sense, they were fictitious self-portraits, yet through them, he was able to capture truth; each imagined writer embodying a different facet of human emotion and sentiment. Together, these varied personas offered a composite, collective portrait of who Pessoa truly was. Pessoa’s concocted heteronyms included distinct literary personas, such as Ricardo Reis, Alberto Caeiro, and Álvaro de Campos, who each professed a different writing style. They showcased Pessoa’s versatility, projecting multifaceted perspectives, with a self-referential literary voice. His Book of Disquiet, published posthumously, approximately 50 years after his death, offered a sense of anxiety or discomfort in coexistence with other more contemplative evocations of the self. Like Pessoa, who once said, “to pretend is to know oneself,” Monteiro presents guises that, while arguably fictional, undoubtedly portray honesty and truth. She makes human experience an exploration of the plentitude of the self through these aesthetic roles. Thus, it can be said that Ana Monteiro’s paintings serve as heteronyms.

The exhibition at CK Contemporary is about the human experience and its endearing complications, which simply cannot be captured by the occasional self-portrait (which would likely be singular, in dress, in countenance, in historical placement). The plurality of ostensively distinct subjects allows us to experience the author, or in Monteiro’s case, the painter, as a fluid being with varied and ever-changing aspects. Just as The Book of Disquiet is autobiographical, Monteiro presents a collection of thoughts, moments, and pictorial aphorisms, seemingly fragmentary and enigmatic reflections evoking a wide range of solitude and melancholy. The paintings have many scattered references allowing for a myriad of meanings: from the outline of an apple suggesting appreciation to a favorite teacher or a red hat worn by Vita Sackville-West (In a distant land once lived a lady), to child-like renderings of seemingly cut-out and collaged paper fish renderings (Some Hidden Soul Beneath), to landscape elements taken from a Botticelli painting (Rapunzel). Monteiro reuses and alters titles referencing Marcel Proust, Oscar Wilde, and Alfred Tennyson, evidencing her literary knowledge and influences. She and Pessoa both embrace imagination, particularly how we pluralize ourselves, to live simultaneously as distinct subjects. They are not synthetic selves, but authentic means to express ourselves through the referential nature of living. Some of the historical references to literature are direct: she paints various vignettes within the paintings (e.g., The Importance of Being Ernst & Make Believe). Although distinct and stand alone, literally in windows or boxes, they don't appear disruptive. These pictorial musings help to slowly and quietly build a persona, one which allows us to explore these digressions without recourse to traditional veritas.

One of the themes present in the work, according to the gallery’s promotional material, is Monteoro's relationship with motherhood. She says, "Since my son was born, I became very aware, and very reminiscent of my own childhood, and it has been a very acute thing to experience. A multilayered feeling of both joy and sadness and everything that goes in between." She has experienced the cascade of emotions as her son attends the very same school Monteiro did as a child, dislodging all kinds of repressed memories, "It is quite a sensorial and emotional experience for me to be there. It is like a time machine. The smells, the furniture, the light...all remain untouched, and in a split second, I'm 7 years old again," she reflects. The paintings thus project her engagement with not just her position as mother but her relationship to a particular time and place. Holding both these related sensations allows a poignancy that wouldn't otherwise be possible. However, an exhibition about motherhood devoid of renderings of children is curious. She atones herself by using referential details of youth interspersed with adult concerns. All of the self-portraits are bereft of any direct hint of joy or laughter. Rather, Monteiro presents herself repeatedly as expectant, pensive, or anxious. There's something uncomfortable—a sense of disquiet here. She is both adult and child, reflecting on the symbolism and constructed pretense that she now contains, recognizing that she has become something distinct from the innocence she once held.

Another literary influence that is congruous to Monteiro is Clarice Lispector (1920-1977), a Ukrainian-born Brazilian novelist and short story writer who also pursued diverse narrative forms emphasizing introspection. Often utilizing interior monologues that present the self as a dynamic construct, complex and fragile, in resistance to linear time, Lispector and Monteiro share a general objective of excavating the constructed self. Lispector believed the self was fluid, something that must be created from within. Monteiro likewise resists the notion of a fixed personage. Through these inventions, emotional states that might otherwise be too challenging to confront are offered in alternate forms. The author can present them to us, yet have plausible deniability that they are certain. The self is both a mask to hide behind and a platform from which to offer revealing possibilities. Monteiro is rejecting notions of a fixed self in favor of a vision that they are malleable and fragile. Importantly, restrictive and limiting versions of the self can coexist with emancipatory ones. The self is paradoxical because it is ultimately a creation of, well, the self. Its elusiveness is precisely due to the constant struggle to know the “I”, while at the same time, offering a symbolic connection to the self of the past.

Ultimately, Monteiro’s focus on melancholic sentiments in her self-portraits, downcast portrayals, and tight-lipped renderings raises questions about how the unportrayed emotions affect us. In philosophical circles, the privation theory of evil is the doctrine that evil is merely the absence of good. It undermines the idea that evil exists on its own and essentially presents good as the foundational value. In other words, something not present can exist and is paramount to what is shown, even when it isn't overtly spoken about. Is there a privation theory of emotions in Monteiro’s work? Ultimately, Monteiro's doleful presentations seem to suggest, and even allude to, felicity through its absence in these paintings. Vignettes representing youth and sentimentality give these works a hint of nostalgic joy and playfulness, emphasizing the distinction between representation and actual truth.

(L) The Tempest, oil on linen, 27.5 x 23 inches, 2025.

(M) Rapunzel, oil on linen, 25.5 x 15.75 inches, 2025.

(R) The Light of Wilted Suns, oil on linen, 23.75 x 19.75 inches, 2025.

Monteiro remains unfailingly elegant as she channels a sense of otherworldliness through the unexpected language of portraiture. The selves she creates exist simultaneously, dissolving the traditional notion of the self-portrait as a singular emotional offering. By painting a range of selves, she reveals the coexistence of multiple interior worlds. In doing so, she transforms the genre from an act of self-presentation into one of self-expansion; a gathering of who she might be, including the emotions she tends to evade. Monteiro tells us she can be all of them at once.