William Rhodes

William Rhodes is a sculptor and mixed-media artist known for integrating craft, cultural memory, and spiritual symbolism in his work. He holds an MFA in Furniture Design from the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth. His artistic practice incorporates found materials, textiles, and community collaboration.

Based in San Francisco, Rhodes has dedicated over a decade to working as an artist and educator within the Bayview–Hunters Point community. His experience includes teaching art in public schools and various community programs. He also established an intergenerational art program at Bayview Senior Services, where youth and seniors engage in collaborative projects that celebrate shared experiences and cultural heritage.

Quilting is a significant medium in Rhodes' work, serving as a tactile and historically rich method for storytelling and fostering deep community engagement. Notably, he spearheaded the Nelson Mandela International Quilt Project, which connected young people in San Francisco and South Africa through the creation of quilts and meaningful dialogue.

His creative works are featured in numerous galleries and museums. Notably, his art has recently become part of the collection at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.

The following are excerpts from William Rhodes’ interview.

Hugh Leeman:

You grew up in Baltimore, Maryland, and have this incredible backstory of how you began connecting with community artists at an early age. Can you share that story?

William Rhodes:

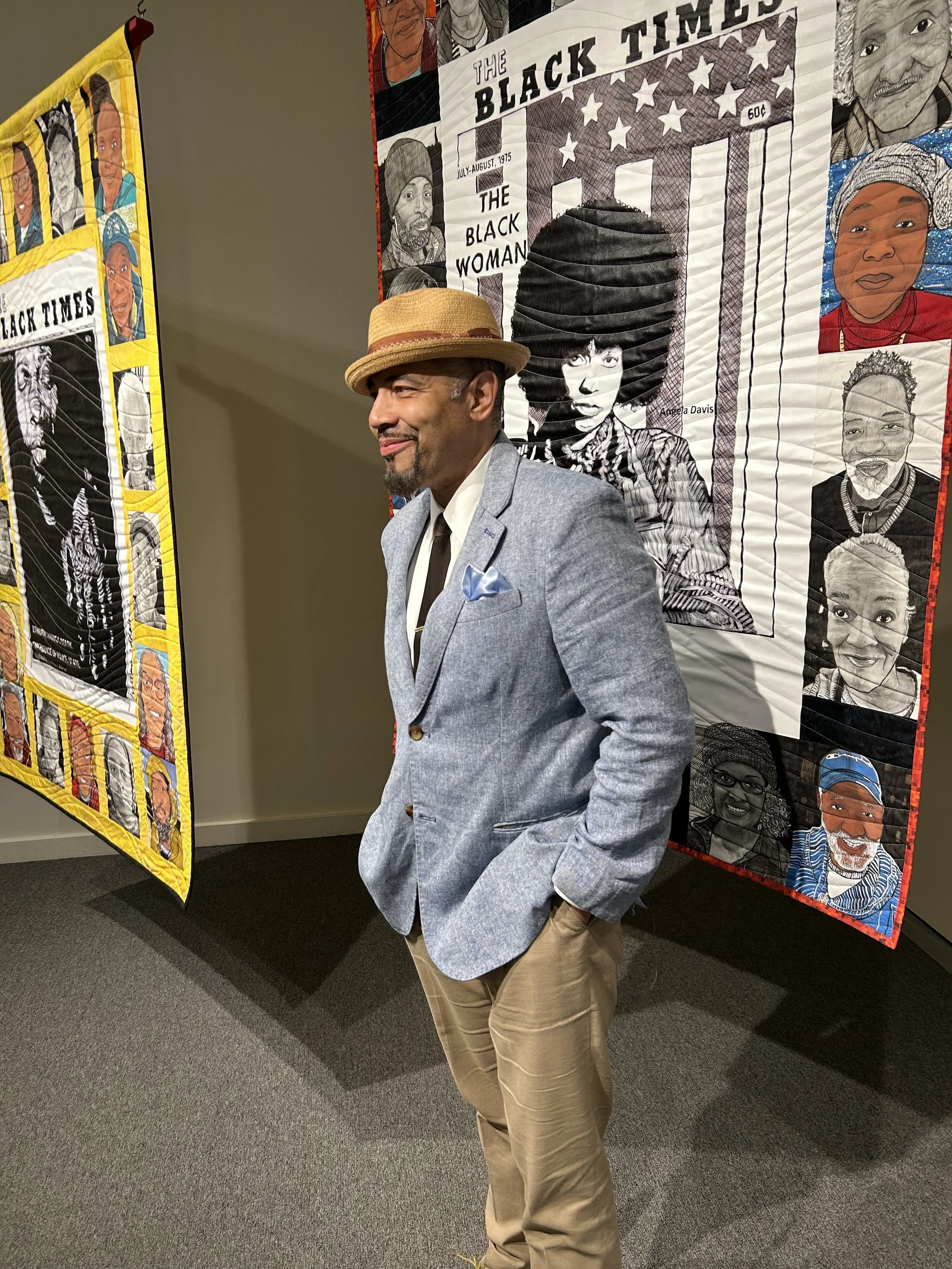

Yeah, it's interesting. So I didn't realize I was connecting with so many community artists, activists, and just amazing people. Until you know, my dad had a magazine called The Black Times Magazine, which ran from 1968 to 1978, and he had a little office, and there would be all of these kind of way out, quirky, creative people that were involved in the community that would be there, it would be like this little gathering. But it was all under the guise of my dad's magazine. One person who really stood out to me was this woman by the name of Joyce J. Scott. She's literally a living legend, and she's a MacArthur fellow now. At the time, she was younger and just getting her career going, but she was always involved in the community with politics and activism and things that were happening all around. So I was really surrounded by that. But again, I was so young I didn't really understand what all of that meant, and I just kind of sat there to try to understand and take everything in with all of this political talk, artistic talk, impacts of community, all of this dialogue just floating around the room.

HL: At what point in time did you think, I want to be an artist? How did that happen?

WR: Art found me. You know, Baltimore was amazing. It was during a time when there was a lot of civil unrest and a lot of changes happening. So Baltimore was a great city, but it was a tough town, too. I got bullied quite a bit because I was small. I stood out, and I would sometimes get beaten up and had some physical issues happen, and I wanted to play sports. But I was small, so I didn't. I couldn't really excel the way I wanted to. It was hard for me, because these guys would run all over me. So I found myself in my room making art, not because I was like, Oh, I want to be an artist. It was just that I could start to create these cartoons and these characters of myself, where I could become a big, strong athlete, or an amazing superhero, or a person who could swoop down and save the day, like I could control that narrative. I didn't realize that was what I was doing, but that was my way of healing. My dad encouraged me because he was. He was an artist, but he unfortunately had to work and support his family, so he never could get his career going the way he wanted to, but he would still kind of take the time to take me to museums when they offered free workshops, or take me somewhere to meet an artist, and just see what was happening, because I guess he saw that art was something that I gravitated towards.

HL: I want to connect what you just shared with what you shared earlier about your father's magazine, The Black Times. This is a powerful civil rights era publication that your dad started, as you mentioned, from 68 to 78. This is an incredibly interesting time in America's history, and it spotlighted the voices of black activists, artists, and everyday community members who were often ignored by mainstream media. Can you talk about the emotional significance and the personal meaning in referencing the work of your father and other black activists in your current art practice?

WR: Looking back at when my father passed away, he's been gone for now almost 20 years and when he passed away. It really made me become aware of how, it's sad to say, but when he died, I realized the importance and the impact that he had on me and the community around him. When I started producing, these quilts that were using the covers of my father's magazines, or even images out of his magazine, were my way of honoring him. It became a kind of discovery for me. It created these flashbacks. So it started to make sense like when he would have Angela Davis over, when my dad did a story on her, and she was holding her Communist card, and my dad put the flag behind her, it seemed really silly to me at the time, and didn't make any sense at all or having people from the Congress of racial equality come to the House. It didn't really resonate until he passed away, and I realized just how important this work was in history. It has influenced me down the line, now that I'm older.

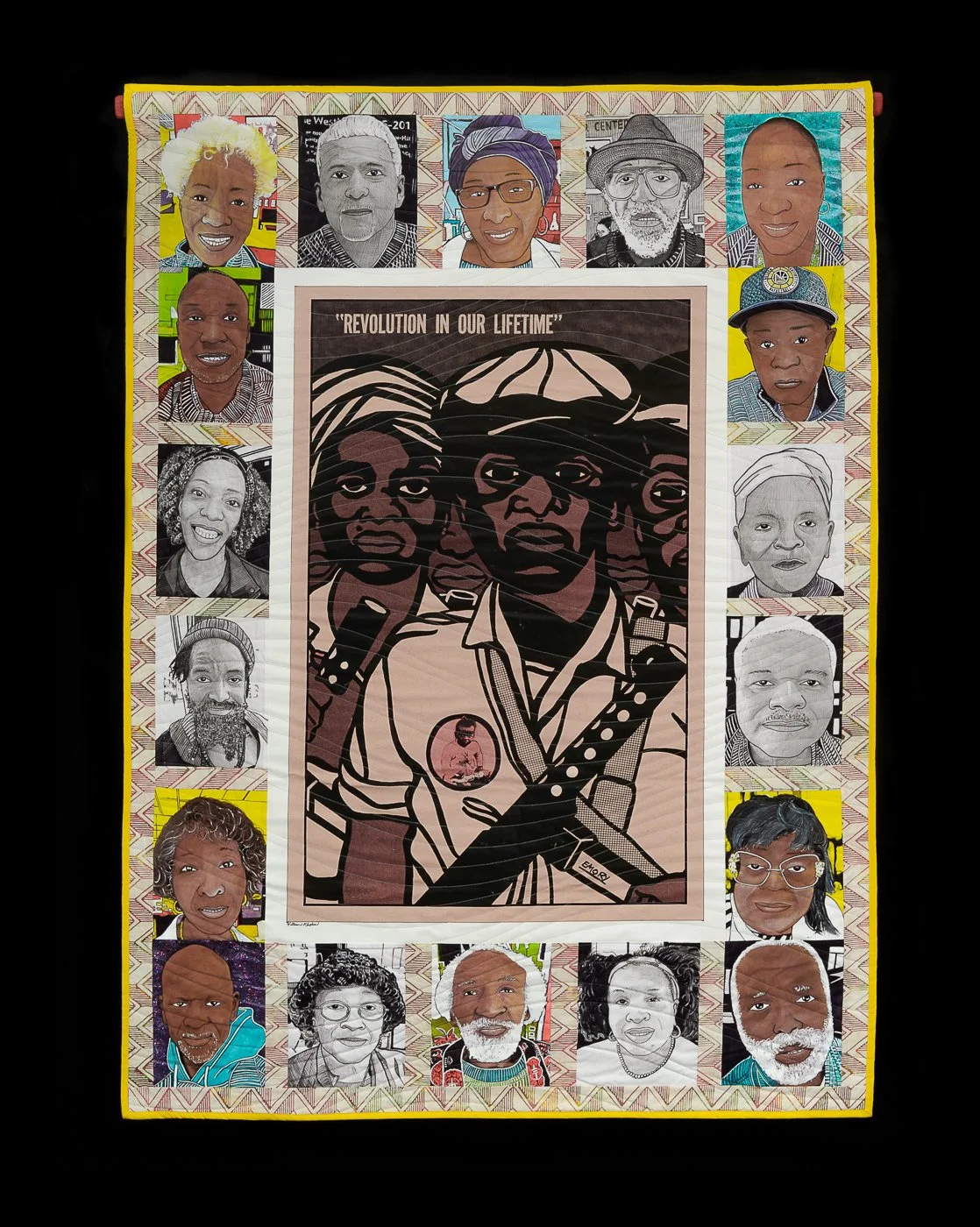

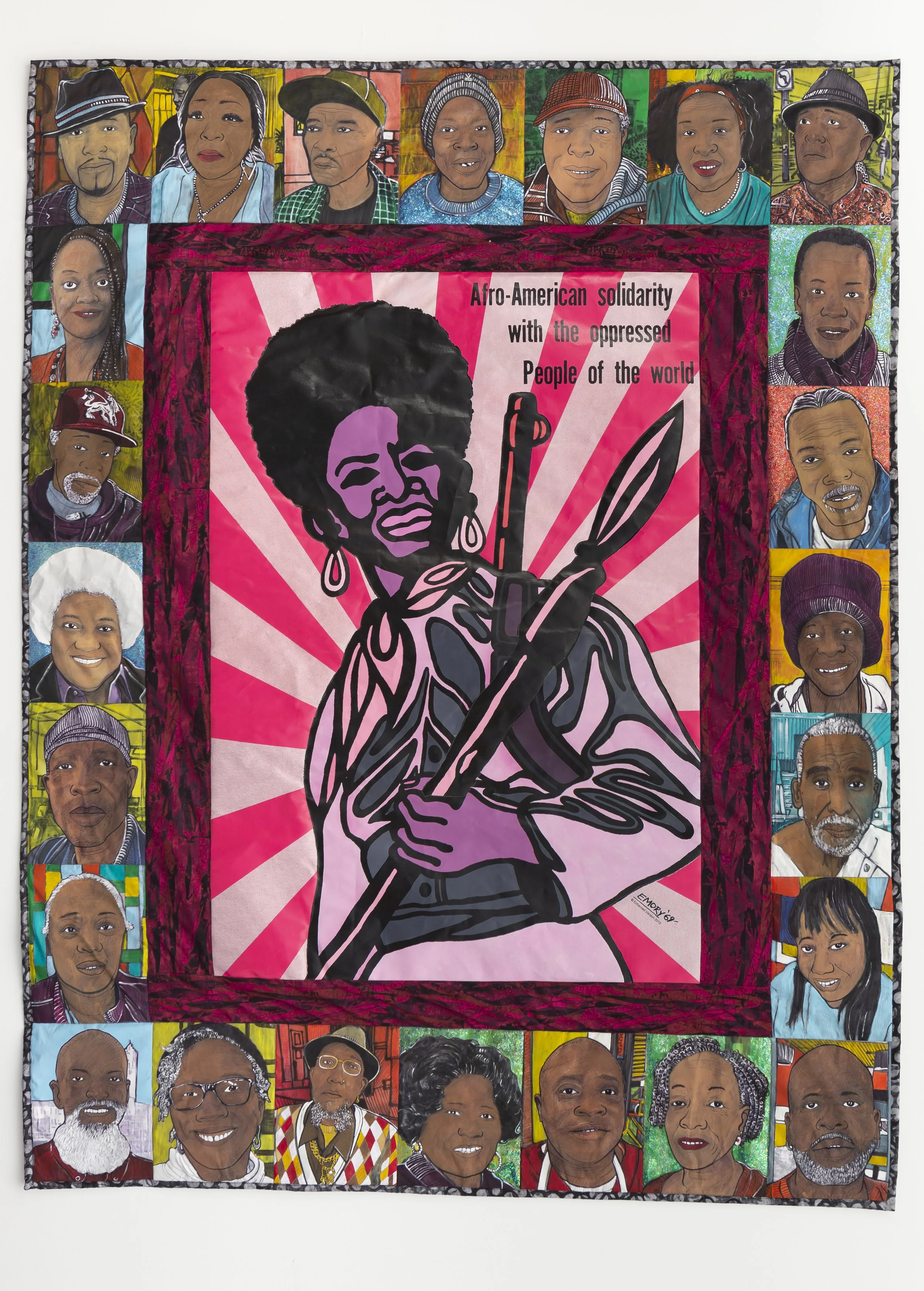

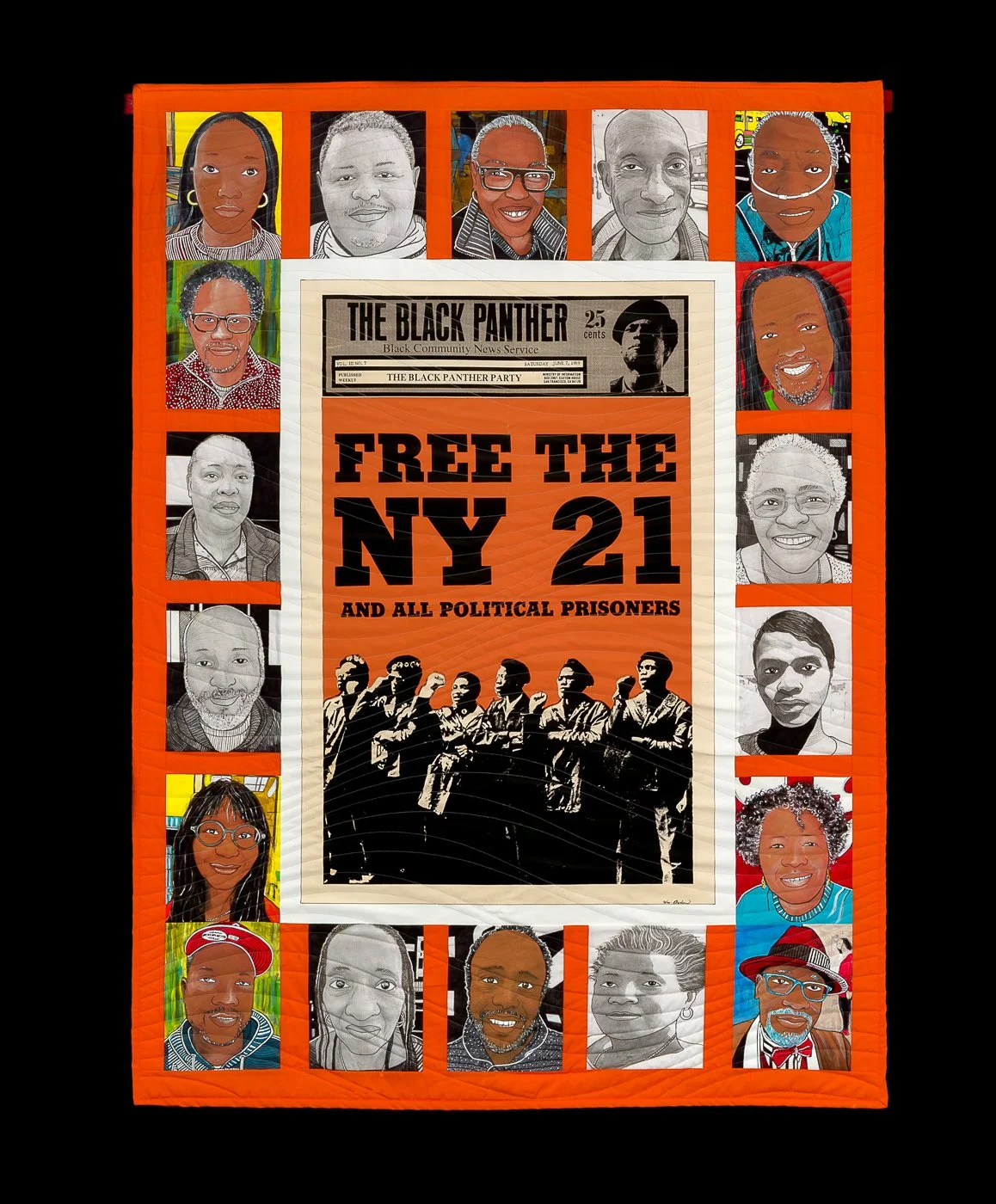

HL: To pull on that thread a bit further here, as there's something fascinating taking place in this, in your current work, and the show you have coming up in London, where you collaborated with Emory Douglas, the iconic Minister of Culture for the Black Panther Party, on pieces for the show. What did that mean to you to collaborate with a person who was so significant to the Black Panther Party?

WR: It was number one, such an honor, he really understands that community work and activism is something that you don't just keep to yourself. It's something you spread and share with other people. So his theory is he passes the torch to a younger generation, and I'm getting old, but I'm a little bit younger than him. So he passed that torch to me and was so open and willing to share. The ironic thing is, it became like a flashback for me, because I would see all of these iconic images of the black panthers. And this is stuff my dad had around, you know, like he would have the newspapers, which, unfortunately, I don't have anymore. It was commonplace to have these kinds of pamphlets, Black Panther papers, and information, and all of this great stuff around me. And I just didn't see any value when I was a kid. It was just regular stuff, but it brought back all those great memories and my understanding of all of this stuff through working with Mr. Emory Douglas.

HL: Art can lend itself to ivory towers. Yet central to what you do is community creativity and collaborations. What's the importance of this in your art practice?

WR: It's huge. I work with Bayview Senior Services, so I'm around seniors and the community every day. I see the impacts of homelessness and food insecurity up close. I felt I had to do something, and art became that something.

The people I work with often help make the art. They're also the critics. Instead of major publications weighing in, though, I appreciate that it's Miss Mary saying, "My grandkids need to see that portrait," or asking, "Where are you going with that piece?"

During COVID, families came to me asking for portraits I'd done of loved ones who had passed. They had no other images. That's when I realized these portraits weren't just art, they were records, memorials. That meant more than any gallery show.

A lot of the people I work with have never been to a museum; they don't feel those spaces are for them. But they'll come to see a quilt with their grandmother on it. That kind of connection taps into a different world, and that's the world I want to be part of.

HL: Quilting plays a big part in your art and activism. Can you share the significance of quilting in African American history and how it connects to your Community Knotted Quilt project with communities in San Francisco and London?

WR: From what I understand, some of the earliest quilts were made by tying scraps of fabric together, no thread, no needle. You'd cut fringes and knot pieces into a single quilt. I love that idea: simple, communal, and resourceful. People added whatever they had: old shirts, jeans, rags. Each piece carried someone's story.

I grew up around quilting. My aunts and cousins quilted. Joyce J. Scott, who was around when I was a kid, quilted. Her mother, Elizabeth Scott, was also a well-known quilter. I didn't care much at the time; I just saw it.

My real entry into quilting came later, when I saw the African American population in San Francisco shrinking fast. I wanted to document people before they disappeared from the city's story. I'd approach folks on the street and offer to draw their portrait. At first, people thought I was a cop or a spy. But when I mentioned adding their portrait to a quilt, something clicked. It made sense to them.

So quilting became my medium, not because I'm a master quilter, but because it was the right tool. If ceramics or wood had worked better, I'd have used that. The mission was always to tell people's stories and connect with the community.

HL: You've also worked with communities abroad, in Cuba, Egypt, South Africa, and Italy. How have those collaborations shaped your art, especially from a non-Western perspective?

WR: In places like Aswan, Egypt, or Havana, Cuba, I hand people a piece of fabric and say, "This is your canvas. Tell your story." With a translator, I ask them to share what matters most in their lives. What they make often reflects deep cultural values, food, family, and tradition.

And they can add anything, buttons, utensils, whatever sticks to fabric. One person used spoons and forks to represent how food connects communities. In many cultures, you don't talk business until you've shared a meal. That ritual became part of the story they stitched.

It helped me realize that storytelling through art doesn't have to follow Western norms. These collaborations expanded my understanding of materials, meaning, and memory.

HL: You mentioned your mission earlier—to tell your story through whatever medium fits. With recent shows in Oakland and an upcoming one in London, what message are you trying to convey?

WR: My mission is to show that everyone has a voice and value, especially people who are overlooked, unhoused folks, and those living on the margins. In cities like San Francisco, it's easy to walk past someone suffering and not see them. Society turns poverty into something criminal.

I want people to know that everyone has a voice and everyone has value. A lot of the people in my work are unhoused, and I've seen how, in a city as wealthy as San Francisco, we can walk past someone starving on the street and not see them. I'm not blaming anyone; it's how our society functions, and I have to check that in myself, too. We get desensitized. People become poor, and then they become villains in the public eye.

"House of Ibeji"; Reclaimed wood, pencil, pen, paint, thread and neon glass; 26in x 30in x 6in

WR: My mission is to show they still have worth. Everyone has a purpose, even if it doesn't align with what society expects. I don't believe anything or anyone is here by accident. Once you've done what you came here to do, you're gone.

That belief drives my work. I want to make people visible. That's part of why I use neon. Years ago, somebody said to me, "You know, you could put neon on a piece of crap", you know, if you take a piece of art, people may just walk past it. But when you stick that neon on and turn that light on, people are drawn to it like a moth to a flame. Whether they like it or not, they stop and look at it to try to understand it more. So that's part of it. I want these voices to be electrified like neon.

(L)"MAN"; Reclaimed box, pencil, ink on paper, paint and neon glass; 22in x 18in x 10in ,

(R) "Gone Mother"; Reclaimed shoe, photo on fabric, paint and neon glass; 12in x 5in x 5in

HL: That's beautiful, you are an inspiration, and passing that torch on from one generation to the next. Thank you for doing what you do.

WR: Yeah, thank you so much.