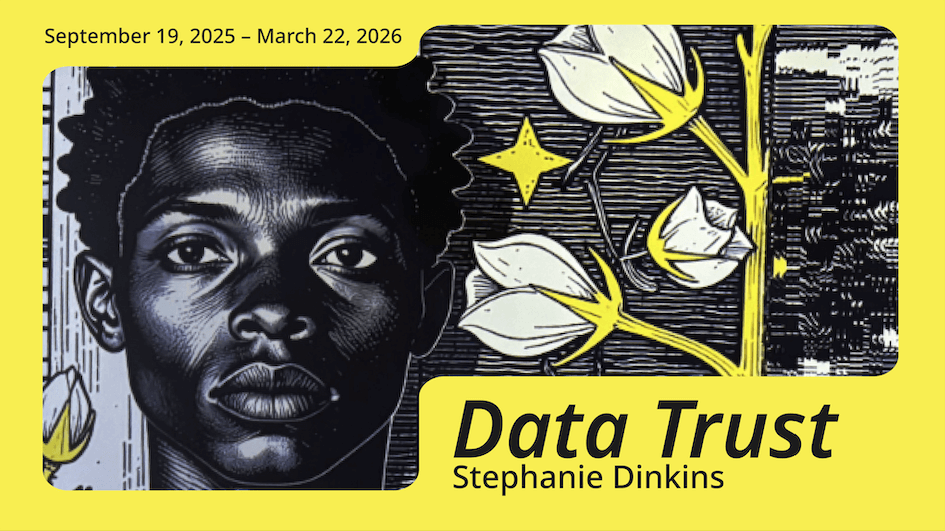

Stephanie Dinkins

Stephanie Dinkins is a transmedia artist whose work intersects emerging technologies and our future histories, leveraging technology and storytelling to challenge and reimagine the narratives surrounding underutilized communities, particularly those of Black and brown individuals. Her work centers on creating care-driven, equitable tech ecosystems by valuing and intentionally sharing our personal and community narratives as the data and algorithms they are and have always been. Dinkins, who holds the Kusama Endowed Chair in Art at Stony Brook University, has received numerous accolades, including the inaugural LG Guggenheim Award, Mozilla Rise25 Award, Schmidt AI 2050 Senior Fellowship, and recognition as one of Time’s 100 Most Influential People in AI.

Her groundbreaking work has been featured in The New York Times, Wired, BBC, RightClickSave.com and more. She exhibits and publicly advocates for inclusive AI internationally at a broad spectrum of community, private, and institutional venues, including a related public art commission with More Art, Brooklyn (2025). Others include Brooklyn Academy of Music, ZKM|Center for Art and Media, Stamps Gallery at the University of Michigan; de Young Museum; Smithsonian Museum of Arts and Industry; Espoo Museum of Modern Art, Finland; and the Ford Foundation Gallery.

All photos are by Keith McCullom, they document Stephanie Dinkins’ Data Trust, a multi-media installation at ICA San Jose.

The following are excerpts from Stephanie Dinkins’ interview.

Hugh Leeman: Stephanie, you've spoken about how during your childhood, your grandmother's garden acted as a way of drawing people in and building community through a practice of making beauty and places of conversation. How did this early experience of your grandmother's garden as a place of community building influence the way that you approach your art and technology projects?

Stephanie Dinkins: Oh wow. Cool. You know, I think that my practice is actually, in some ways, my grandmother's practice, in a very different sphere, but this idea of using something, whether it is a flower or technology, to draw people in and then have conversations that you might not otherwise have had. Right? So, I always feel like in a way I do all this work to create these crazy things that pull people in or at least get their brains turning in a different way and allow them to walk with thoughts. And if we get to talk to each other at some point in between that, that makes me happy. It feels more direct to me, right? Like it doesn't feel like a leap, just a different visual method.

HL: Yes, that's wonderful. I want to come back to your grandmother later. So, through the project Al-Khwarizmi, you've been teaching AI literacy in communities of color saying of this, "It's really important that people do dive in, get involved on whatever level they can. Maybe that just means understanding the technology or just calling it out." Can you talk about how engaging with AI in one of these workshops or art contexts has helped community members dive in and challenge the technology that's impacting their lives?

SD: Yeah, sure. You know, I think, well, let's start it in this place. I've been doing this since 2014, right? So, in a way, it's a really different landscape than then. Al-Khwarizmi was maybe 2016, 2017, still where AI was happening kind of in the background of our consciousness. Now it's really foreground. And so then it was very much about, "Whoa, I need to talk to my neighbors about these things that are impacting their lives." From things that were so simple like, "Well, I live on one side of the street, you live on another, we see completely different prices in our catalogs because of the way the algorithms work and ways that things are broken down." Then I think I live in Bedstuy, Brooklyn, a neighborhood that is, or was, primarily black and Caribbean, under-resourced, and thinking about what it means when you start hearing, "Oh, well, judges are turning to algorithms to decide how long people go to prison, why they go to prison." And within that system, there is a historical bias, right, in terms of what's already gone. Because if you use that data, then it's what I call like a black tax gets put on because already statistically more black folks are being put away. And so the way that justice is doled out or the way that time is given based on the past pushes towards longer time in the present, just because this information is being used. And so then the question becomes like, "What do you do about that?" A, I think you have to know about it. You have to know that there's something that somebody is referring to that is taking in historical biased historical context and using it to do something in the present against you because if you don't even know, you can't do anything about it. And then it's about, "Well, how do we lobby to get that changed?" And then in that time, you know, it's interesting, there are all these people who have been lobbying against the biases in these systems to make them change and they've changed in a lot of ways. Right now it's very much different because now and and then to an extent, I want people to actually start to use the tools a bit, right, to get their hands dirty and start to understand even if it's simply input-output. Because what I noticed in my own use is that the more I use the technology and looked at it, the more I could see cause and effect, right? And knowing that cause and effect allowed me a lot of latitude to then think about how I might change it or why I might think it's important to change it, why I think it's important for my neighbors to think about changing it. And so the idea is conversation at the very least, right? Then use at whatever level we can get people using, curiosity, right, for sure, because I think that keeps people in it once they do start using and then bringing it forward with things that people are actually interested in. Like I, for example, did Not the Only Ones about my family because it was something I could think about that I thought I would stick with long term, despite all the computer time. And I've worked with kids who are into hip-hop. And so if they want to think about their favorite hip-hop group using AI, I'm all for that because then we get them inside, right? And once you're inside, maybe you get seduced in a little bit more and more and then it's like, "Well, not just taking it for our face value." Right now, let's examine what it's doing. Think about how it is. Then think about how, in a way, we're co-opting some of the technology to do what we want it to do versus what it does or how we're supposed to consume it. And I think that goes across the board from then to now. Like, yeah, they tell us how we're supposed to consume it, but does that mean that's what we have to do? And then if we agree that it doesn't mean that's what we have to do, then how do we influence it? Like what influence might we have when we're told that we have none? Because we're often told we have none, right?

HL: You just mentioned something very interesting: Not the Only Ones and this connection to your family. It's exhibited widely, at museums. You've intentionally kept the piece Not the Only Ones as small data collected from your family in place of using these large, bias-laden data sets. Regarding this, you said that, "If you fixed it all the way, it wouldn't question the culture." This is fascinating. Can you talk a bit more about how these flaws in the piece, Not the Only Ones, function as a critique, questioning the culture?

SD: Yeah, I think everything that Not the Only Ones asks of visitors, in particular, so people who come to see it, you know, we come with expectations, especially these days because you can talk to Siri or Alexa or whatever and get this answer, and it's pretty direct, and most of the time it's pretty okay. Not the Only Ones, however, you know, might answer, sometimes it refuses to answer. Sometimes it does its own thing completely and it plays with people's expectations. Like I've seen people get really angry with it because it's not communicating in the way they want. I've seen them try to use strategies that they use with these other models and they don't work. And what that does, I think, or I hope, is kind of shake up what the expectation is and how we might be deploying it and and make us think about what it means to kind of what I call nurture a system into being versus expecting the system to serve us out of the box in the way that we expect. I often think of this in terms of kids. I think it's easy to explain it because if you've ever watched a kid like order an Alexa or a Google Home around, right, and have that expectation and then you think about, well, what does that mean for that kid going forward and how their expectations of how the world serves them form? What happens when there's something that does not directly feed your expectations and has its own trajectory and its own way of engaging the world? And I find that really important in terms of Not the Only Ones. You know, I'm at the point where I keep going, "Oh, this piece is so obsolete," right? But at the same time, and that's technologically, right? Stupid technologically at this point. But at the same time, it holds itself. It holds our data, and when I say our, I mean my family's data, in a way that carries forward still in a way that both resists and supports, and I find that, well, I find that heartwarming, right? I find that heartwarming in a sense, but I find that a way of engaging technology that is better for us and maybe even our mental health. Like I was just talking to a car's chatbot this week and it was very interesting because it's clear that this thing is supposed to seduce me, right? And we're supposed to be friends and buddies and I keep going, "Well, what does this mean?" Like there's no resistance. It's just trying to give me everything I want. What does it mean for us? And how is it lulling us into something that is long-term really not sustainable?

HL: Oh, I feel like that goes right back to what you were saying about the idea of something that feeds expectations. And imagine if you're seven, eight, nine, ten years old today and this is the world that you're brought up in, and something that just constantly reflects your emotions and feeds you just to keep you on the platform. You go out into the real world and that doesn't happen. It's pretty devastating. So I want to keep talking about this piece, Not the Only Ones. To give a bit of context, this is coming from the voices of three generations of women. It's you, your aunt, and your niece. In what ways did this personal, intergenerational collaboration produce a unique artwork and spark dialogue of healing within your family and the potential of that beyond the family?

SD: Yeah. Well, you know, one of the reasons I wanted to do it was because in my family there were a lot of unanswered questions, right? And I was just trying to get at information that I've been curious about for a very long time. For example, my great-grandfather owned land in Georgia, right? And this is two generations ago. My grandmother was born 1913. So this is 18 something. And I'm like, "How or why?" And nobody has this answer. So I thought, maybe if we sat down and tried to discuss it we might get something out. And I was right, because the formality, there was something about the formality that opened up people to give and there was also this thing where my aunt would open up in different ways to my niece and I. And so there was a ping-pong effect of the way the history came out. And so for the family, it became that, like, this generative idea of just getting the information you've always wanted to know in a way that allows different eras to commune. And I'm now I'm using that again. My uncle just has been telling me some really fascinating stories, right? And it's just a way to coax this information and that something about the formality did it. And you know, dealing with my family, it's like, "Well, we love you, so we'll do this thing." It's not much more than that. It's like, "What is she doing now? Okay, I guess we're along for the ride." And but the ride has been long because this project's been going on for a long time now, right? Yeah. And and it just allows for a I think more about us to survive. Right. Beyond which I really appreciate and for those relationships to remain strong.

HL: This is beautiful. To pull us into somewhat more of a macro perspective than the family unit here and looking at the idea of storytelling. There is a previous interview where you said, "I would never say I am a technology artist, although I do think technology matters a lot on the social side. I'm an artist who always thought about community." Why is it important for you to frame identity around community and storytelling rather than technology?

SD: This is a really good one. I don't know, like community... well, I'm going to bring it back. Maybe I feel like I come from or was raised in strong community or in a community that really needed itself to survive the conditions it was in. And what I mean by that is like, we're a black family. We grew up in towns where there weren't very many other black families and the ones that were there knew each other and they would come together and there was a support and sense of community and intertwining of these families that was pretty tight, right? Yeah. Yeah. That allowed you to live in this environment and and care. So I call it we we were circle the wagons people, right? You have a community, you go out into the prairie, you circle the wagons. When people need something, you pitch in. And when I think about that as a model for greater society that we seem to have forgotten, right, it seems like that is a thing we need, whether it's for making things that are technological or making things that are just let's say food, right? Just sustaining ourselves through food where we're not totally dependent on the institutions that provide that for us. And when I think of that right now, it's like, "Oh, if I wanted to build a house, which of my neighbors would I call to help me?" Yeah. And I can't answer that question. I'm sure you would pitch in, but it's not like the expectation is we're going to stand together and do this thing. And when I think about the world we're facing right now, it seems to me that this idea of community and who's going to stand up with us is really important. And how we're going to stand up is really important. So the question for me is more, "How do we get the conditions to allow us to see each other and serve and support each other?" And I really don't care what or how that comes about. I just want to see it happening. And I've noticed that lately for me that is really conversation or trying to draw others into conversation or storytelling, right? Which is ancient.

HL: This idea of the black artist. This is something that you've spoken on quite a bit. And in 2020, your manifesto Afronowism, you wrote about, all of the social turmoil that's taking place in 2020. And you posed the question that why must black artists always reference the past or speculative futures, noting that, "We're still fighting for elusive equality. But what about now? Why does much of our work have to be based on history or a speculative future to be recognized by the establishment?" Can you talk about how you are thinking about centering your artwork in the present?

SD: Yeah, you know, it's interesting. It's interesting to hear that because I'm like, "I center it in the present," or at least I think the doing of it is very centered in the present because in a way, I look towards the past and the future, right? But to me, both of those moments result or come out of the moment that we're currently in. And I want to be able to live or create from where I am and feel that like, it's not that the work has to be taken up or respected, but at least there's a chance for that, right? And the way I've thought about it in the past is like, you know, we're often offered this carrot stick. It's like, "Well, do this and maybe this will happen out there." And it's like, how long do you wait for that to become a reality, right? Instead of just making into your moment what you feel that you need to do at this moment. In a way, it's for yourself and your community. And then maybe that will take on in the general atmosphere, but I'm not sure it will. But the making is sure to have an impact, right? Like, and thinking about what it means to do this now instead of always dreaming towards an out-there future or dredging up the past that kind of like staples us in place, right? And that's what I kind of feel like it's like the past, at least the black American past that I feel like I've been given or taught has been one that's meant to kind of hold me in place. And I feel that we and black people as a community many times take on that information and hold it, right? Or believe the hype of the histories we've told as if we've not done anything and we're not contributing. And in one sense we know this is not true but in another sense or maybe subconsciously it's like we don't believe that the world is there for us. To explore deeply and freely. And my question is, "Well, how can you take on this idea that nope, I can explore the world deeply and freely in this moment and I don't have to be afraid of it. It is mine as much as it is anyone else's and I will do that." And the way I often explain this is like, you know, one of the things I think that most people should do is take a drive across this country, although this is a moment where I think this is harder to say because of how crazy we've become. And when you drive across the country, it's like, you know, you're driving across place, time, many different ideologies. But at the same time, I don't know if I've just been lucky, but the encounters are most people are kind of generous, right? You know, where you when you're somewhere where you have to be careful, maybe like I have been places in my car where it conked out with a friend and we were in the middle of nowhere, Georgia. I'm black, she's white, and she's like, "Let's just get out and go check." And I'm like, "There's no way in the middle of the night. I have no idea where we are that we're just going knocking on anybody's door, right? I can't trust that." But like it's interesting to me that she's like, "For sure we can trust that, right?" I'm like, "No, let's just wait until at least daylight and then we'll figure out what's happening." Right? And that's like a different kind of consideration. And the question for me is like, "How do how do black folks, how do brown folks get to live without these different heavy considerations that put fences around their lives?" Right? If we think now, we're thinking about ICE. Like, "I can't go to Home Depot now without and see the guys working waiting on the side to be day laborers without thinking about, oh no, what are they putting on the line by being here?" Yeah. "And what does it mean that they're here even though they know the stuff that's going on?" Yeah. Right. Um and so how do we get out of that corner that we built like or the corners that were built for us? And that I think is the brains of both the black and brown folks and everybody else, right? Because the environment is shaped by all the minds that shape it, right? And we watch that now and it's like, "Well what does it take to reshape that environment in a way that allows for people to live like just live?" .

HL: Thank you. I want to talk in just a minute about your exhibition here at the ICA San Jose, but first before we get to that, I want to go back to 2018 and you really had this crystal ball in many ways of looking ahead. This is seven years ago, and now in the world of tech, is a light year ago. It's so long ago. And you said that, "Social issues that are too urgent to deny exist. It's imperative that black people and other people of color are involved in making decisions on this. It's a greater than any urgency I've ever felt." A lot has happened since then. How have you seen the conversation around AI inclusion and AI bias evolve since you first emphasized this back in 2018?

SD: Well, there's been so much, right? Like I always talk about what I feel is all these black women who have done a lot of work towards this, right? Ruha Benjamin, Meredith Brousard. Like there have been books, there have been people like trudging on to make change and we've se it's it's interesting because you can watch it, you can see where the advocacy and the changes have come, like where things have changed and where things still have a long way to go, right? So I feel like there are people doing this work, there people have been doing the work, we had some changes. But now we're on a U-turn. Right. Like suddenly we are on this turn where the government, right, everything is flipping and it's not only in the AI ecosystem now but we are just blatantly back to, "Well, how do we keep people where we think they should be versus how do we support people so that everyone flourishes?" Right? And so for me in a way it's like the AI version of it is this one that was pervasive and maybe under the skin that wasn't so visible and there were always people working on it and things change but then we're facing a backlash where now it's not even pervasive and under a veil like it's in the AI and there's still things in there but it's also just blatantly hardly in our face out in the open coming at us. And I wonder what the strategies are in terms of now, now what do we do? Like I think about this a lot, right? Because protest like when people are in the street, they're undercounted, right? Now they don't even want to let protest get started. We're bringing in the guards. Yeah. To control things, right? And so for me it becomes about what systems or or ways of being and thinking and making change do we have to be thinking about collectively whether it's an AI or not to kind of bring us back and what does that entail? I always come back to the idea that it comes back to care on a broad basis because a lot of what we're feeling is people who feel like their backs are pressed against the wall and they're going to lose stuff and people feeling that they still deserve stuff and everybody disgruntled and that just can't function. Yeah. So like it's like this is such a hard moment to talk about that because it is it does still feel so blatant and on the surface and I don't know which tools are the tools to get us to recognize to, well, let's say, to get us to come into community on a broad basis and start to work things out. But I do know, I think, that we have to a, be able to listen to each other and speak to each other. Like I'm always brought back to the first time our current president was elected and people were starting to say how they couldn't talk to their grandparents because they voted and it's like that makes no sense. Like there's no way that this functions long term, right? But people that like were still very stratified. Yeah. In this way, it's like, "What gets us, what gets us to talk? What gets us to act in a way that isn't hostile?" And hopefully it is not the extremes because we can eat, well, we're watching the extremes happen around the world, right? Yeah. Yeah. I don't...

HL: I want to connect what you just said, this idea of, "I can't talk with this person, my family member, my grandma, whoever because of, our differences and political perceptions or political views." And connect that with something you said earlier when we were talking about your grandmother's garden. You have this ability that many great educators have, which is to be able to describe something that's quite complex and dynamic in ways that's a very accessible language. If you could imagine the exhibit at the ICA San Jose, your brand new show here, and you're in a conversation with the grandmother who you spoke of earlier in her garden. What would tell her, how would you tell her? She's not seen this. How would you tell her about this project, what you're doing? And what do you imagine her asking about it and wanting to know more about it?

SD: Wow. I think that I would tell her that I've made this space that I hope is a space of curiosity and a space of listening, right? One that allows people to kind of mill around the same thing and maybe have a conversation about it that not is not only about this work but slips into something else. I'm asking people for their story, right? And what's important to them which is really important to me, because what I'm trying to do is in the long run make a data set of care and generosity, right? That puts first, first the perspective of people who are often underutilized. I hate the word marginalized so I try not to say it, but who don't get as much play. Put those stories front and center and not only those stories but from the perspective that they know their story, right? Because I think it's often very different the story that gets told about you or what people think versus the story you know and have lived, right? And the way I explain that is like I feel like I've lived blackness in a way that doesn't often get portrayed on screen. It's very specific and I think it's really rich, right? And it's something that, and this is a lot to say, it's something that I feel like the world would benefit from knowing, right? The ways that we work with each other in my family, in my community, and I'm sure not only my family has this, but people have it. Yeah. And what is it? And what is that secret sauce that if maybe we collected all these sauces, come together to help influence what we are already surrounded by in what I call the AI ecosystem and make it a little bit more survivable, thrivable, supported, right? So I want to just get people to be able to tell their story, think about their story. Because I'm told that we ask we ask questions here, right? And people often say, "Well, these are not easy questions. I have to sit down and think about it." I'm like, "Yeah, that's great. I want you to sit down and think about it. Then what would you give back or how would you retell it from tell the story that that question elicits from your perspective? And then would you be good enough or would you consider gifting that story to the rest of us so that we might benefit from it?" I can't guarantee it. All I can do is make it and then throw it back out into the world and see if it works. Right. And that's what I think I'm trying to do. And that works on the the like ground level. And then I get to tell the story after this that says, "Hey, we made this thing. Look how it functions and people keep telling me this isn't quite possible but this seems to be working on a small scale, why can't we attempt it on a larger scale?" Right? So that's what I would like, you know, I that's how I'd explain it to my grandmother. I'm just trying to influence the systems we live under so that we can live better in a way, right? And yeah, that's that's it.

HL: This is great. I love the idea around that. Let me pull on that thread a little bit further here. So your current work in this exhibition, Data Trust at the ICA San Jose. How do you imagine Data Trust evolving beyond the museum, beyond the institution, and can it be replicated in other communities to collect their stories?

SD: Yeah, I think it can. And in fact, there's a piece that came before this one called If We Don't, Who Will, which is in Brooklyn, Downtown Brooklyn right now. It is in a shipping container where we are collecting people's stories, right? And so we have this small kind of thing where there are people like lab attendants who will talk to people and collect their stories and help them tell and then it represents them on a very different screen set, right? And so, okay, that's one instantiation. And then in one place, you come here to San Jose, like over the past year, year and a half, I've been talking to community members here, right? Having conversations about this. And I think that can be ported in many places. And in a way, I don't care how it gets presented as long as it has this curiosity-like thing that draws people in so that we can have the conversations. So, you know, if we're sitting on a on a what on a beach chair under an umbrella and we get to have these conversations, that's good enough for me, right? So in a way, I think that the project is about the conversation and the rest of it is the spectacle that tries to get people to just participate because we live in the world of spectacle, right? And then just bringing up ideas that, you know, that are maybe thought about in bigger ways than we often think about them. Like this this afternoon, a lady came through and she gave me my favorite, one of my favorite compliments, which is, "My mind is blown or I'm going to have to think about this for a long time." Which if I can get you to walk with a thought, I'm so happy. But yeah, we're telling you, you know, we're taking your stories. We're taking the stories, we've collected them, we're inserting them into DNA, we're going to put those DNA into plants, and we're going to see what happens and how that goes into the land over time. Like, that to me is that thing that starts to pull at you and go, "Yeah, what the heck are you doing? And why should I want to know about it? And how could I help?" Yeah. Right. Right. And so, yeah, we'll we'll take the crazy to get the the good stuff.

HL: I love that. The installation, as you mentioned here, it features living plants from okra to to oak trees and soil. It's been enriched with the DNA encoded story so that the environment itself grows with the input of the community. It's effectively a living ecology. As people contribute their stories and see them themselves becoming a part of this growing ecosystem, what do you envision being the high aspiration for connecting the relationship of technology to community memory?

SD: Oh wow. Well, you know, this is such an interesting question because our extracted data is saying something very interesting to us about this. But one of the things that came out of this is that, you know, the system doesn't deserve our data unless it can care for it correctly, unless it actually wants to hear it. And what does that mean for community memory and long-term memory? Like really, I started with the idea of DNA and the soil and the plants because I wanted to hold on. I wanted to really think about what it means, especially for black Americans, to live on this land that we have claimed to but can't really claim. And what if you took our story and put it so far into the actual soil in an intentional non-violent way that it then held that it couldn't be forgotten in ways that we tend to erase the things that don't serve us, right? What would that look like? And what does it mean to somebody to know that it's there? Right? And so I'm trying to figure out ways to implant encode the very land we stand on with this information, right? So that if the building is gone, the soil stays, right? How do how do we how does that persist? How do we make it visible? And because of the culture we live in, how do we make it sensational? Like if I get my way over long term, this project, especially the DNA with the stories, becomes a forest that hold this information that could hypothetically be extracted. Like we've extracted some of the stories from this DNA already. Hold on one second. And it and it's beautiful because it's mistaken written, but it's also just what came back is beautiful and recognizable. There's this perspective of knowing or this way of claiming space like we have a way of claiming… clearly I'm trying to figure out how to claim things that aren't trying to be given to me in a way or not recognized as something like the community that I come from have really materially contributed to and are slowly slowly slowly getting claim to right. Yes. Um so it's like how do we do that more effectively?

HL: I admire what you're doing and especially amidst the incredible evolutions technologically, the challenges sociologically they're going on and your ideas of saying, "I really just want people to talk," and a spectacle in many ways of of the art and the installations is just to get people to talk. And that's profound because as you mentioned, storytelling, it's ancient. It's prehistoric. It's one of our oldest forms of art, of convincing people, of connecting and it's really being lost. So, thank you for doing what you do, Stephanie.

SD: Oh, you're welcome. I really appreciate that. Thank you for hearing it so well. I had a great time talking with you.

Hugh Leeman: Hey, thank you very much for doing what you do. Until the next time.

Stephanie Dinkins: Okay, take care. Bye-bye.